1 Economic Transition and the Case of China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mysteel Raw Materials Daily Bringing You the Latest Updates on China Raw Materials Markets Tuesday, August 2, 2016

Iron Ore Coal & Coke Billet Scrap Ferroalloy Freight Latest News Analysis Data MYSTEEL RAW MATERIAL DEPARTMENT Mysteel Raw Materials Daily Bringing you the latest updates on China raw materials markets www.mysteel.net Tuesday, August 2, 2016 Currency Exchange 1 USD = 6.6277 CNY 1 USD =1.3265AUD 1 USD=3.2648 BRL ISSUE 292 USD/DMT Mysteel IO Index (62% Fe Australia) Today's Highlight 80 70 Steel mills raise steel prices 60 50 Steel prices rose again. Shagang Group issued the early August’s adjustment 40 policy of steel prices on Aug 1th. Rebar price increased by 70 yuan/ton and 16- 30 25mm Spot rebar’s ex-factory price came to 2480 yuan/ton. Coiled rebar price 20 10 increased by 30/ton and 8-10mm spot coiled rebar’s strike price stood at 2530 0 yuan/ton. High speed wire price came to 2480 yuan/ton, up 30 yuan/ton. Hot- rolled coil products’ prices reached 2800-2830 yuan/ton, up 20 yuan/ton. Jul-15 Jul-16 Jan-16 Jun-15 Jun-16 Oct-15 Apr-15 Apr-16 Sep-15 Feb-16 Dec-15 Aug-15 Nov-15 Mar-15 Mar-16 May-15 May-16 USD/tonne Mysteel IO Index VS Mysteel Shanghai Rebar Index USD/dmt Iron ore price hits high 500 80 Iron ore future price 1609 hits three-month high of 486.5 yuan per tonne 450 70 400 60 in Dalian commodity exchange market, and is set to end July with a second 350 consecutive monthly gain, defying market expectations that iron ore would be 300 50 250 40 dragged down by increased supply in 2H16. -

1. La Chine Et Ses Migrants.Pd

La Chine et ses migrants. Chloé Froissart To cite this version: Chloé Froissart. La Chine et ses migrants. : La conquête d’une citoyenneté.. Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2013, Res Publica. hal-03168530 HAL Id: hal-03168530 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03168530 Submitted on 13 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LA CHINE ET SES MIGRANTS La conquête d’une citoyenneté Collection « Res Publica » Dirigée par Philippe Garraud et Érik Neveu Comité scientifique : Jean Baudouin, Jacques Caillosse, Delphine Dulong, Christine Guionnet, Virginie Guiraudon, Christian Le Bart, Claude Martin et Érik Neveu Agnès Deboulet et Héloïse Nez (dir.), Savoirs citoyens et démocratie urbaine, 2013, 138 p. Guillaume Garcia, La cause des « sans ». Sans-papiers, sans-logis, sans-emploi à l’épreuve des médias, 2013, 286 p. Valérie Sala Pala, Discriminations ethniques. Les politiques du logement social en France et au Royaume-Uni, 2013, 304 p. Élisa Chelle, Gouverner les pauvres. Politiques sociales et administration du mérite, 2012, 290 p. Rémy Le Saout (dir.), Réformer l’intercommunalité. Enjeux et controverses autour de la réforme des collectivités territoriales, 2012, 268 p. David Dumoulin Kervran et Marielle Pepin-Lehalleur (dir.), Agir-en-réseau. -

40Th Anniveisafv of Vistory of Anti-Japanese War Il8 ^!^Iin<I Lue

No. 32 August 12, 1985 A CHINESE WEEKLY OF NEWS AND VIEWS 40th Anniveisafv of Vistory of Anti-Japanese War il8 ^!^iin<i lUe PBBylaBfi SPOTLIQHT 0 'it •> An artisan passes his skills Tin incense burners. onto a young worker. Tin Handicraft Articles in Yunnan Province Gejiu tin handicraft has a history of more than 300 years. Through dissolution, modelling, scraping and assemble, the artisans create patterns with distinctive national features on pieces of tin. Besides the art for appreciation, Gejiu also produces many handicraft goods for daily use. The products sell well at home and abroad. Croftswoman polishes fin articles. Tin crane. Various kinds of tin wine vessels. ^^^^^^^^^ BEIJING REVIEW HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK Vol. 28, No. 32 August 12, 1985 Looking Back to World War 11 In China As part of a series commemorating the 40th anniversary of CONTENTS the worldwide victory against fascism, a Beijing Review article epitomizes the 8-year long history of China's anti-Japanese war (1937-45), highlighting the role the Communist-Kuomintang co• NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 operation played in the war (p. 13). Fostering Lofty Communist Ideals LEnERS 5 Army Aims to Cut Ranks by 1 Miliion EVENTS & TRENDS 6-9 The Chinese People's Liberation Army celebrated its 58th 'Star Wars' Must Be Avoided — Deng birthday August 1 on the operating table — by reducing 1 Army Aims to Cut Ranks by 1 million troops. This reduction is being carried out to remedy Million the problem Deng Xiaoping noted in 1975 when he said, "The China, Japan Sign Nuclear Agreement army should have an operation to cut its swelling" (p. -

Industrial Policy and Global Value Chains: the Experience of Guangdong, China and Malaysia in the Electronics Industry

Industrial Policy and Global Value Chains: The experience of Guangdong, China and Malaysia in the Electronics Industry By VASILIKI MAVROEIDI Clara Hall College This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Centre of Development Studies, University of Cambridge Date of Submission: September, 2018 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Acknowledgments This thesis would have been impossible without the support and encouragement of a great many people that I met during this journey. My biggest thanks go to Dr. Ha-Joon Chang. He believed in me since the very first time we met and all our conversations since (together with the copious amount of red ink spent on my earlier drafts) have pushed me to think harder and improve not only as a scholar, but also as a person. -

Christianity and Gender in Southeast China

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/18940 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Cai, Xiang-yu Title: Christianity and gender in South-East China : the chaozhou missions (1849-1949) Date: 2012-05-10 CHAPTER TWO: PROTESTANT AND CATHOLIC MISSIONS Introduction From the mid-nineteenth century, four missions—the Basel Mission, the English Presbyterian Mission (EPM), the American Baptist Mission (ABM) and Les Société des Missions Étrangères de Paris (MEP)—had a foothold in the Chaozhou region but were eventually expelled from mainland China in 1952. Since 1895, a dozen scholars have published about the history of their activities. In the first hundred years after 1895, nearly all of them were former missionaries or local church leaders.113 From the mid-1990s, historians who had no immediate connection with the missions such as Joseph Tse-Hei Lee, Hu Weiqing, and Lee Kam Keung (李金强) have stepped into this field.114 Joseph Tse-Hei Lee used the archives of the EPM and ABM as well as the British and American diplomatic sources and Chinese municipal archives to reconstruct the expansion of Protestantism into Chaozhou region in the second half of nineteenth century. He describes the transmission of Christianity in Chaozhou, a highly dynamic world with frequent migration and collective violence, which was totally different from more static, agrarian North China115. Hu Weiqing pioneered using the Chinese records of the English Presbyterian Synods at the Shantou Municipal Archives.116 His main interest was in the indigenization of Protestant Churches in Chaozhou. Lee Kam Keung has focused on the Swatow Protestant Churches in Hong Kong. -

Polity and Governance

www.gradeup.co www.gradeup.co Polity and Governance J&K govt declares actions under Roshni Act 'null and void Why in the news? • The Jammu and Kashmir government has declared the actions taken under the Jammu and Kashmir State Land (Vesting of Ownership to the Occupants) Act, 2001 or 'Roshni Act', as null and void. Reason behind this move • The Act, which was repealed in 2018 by then lieutenant governor Satya Pal Malik, was implemented with the aim of boosting the farming sector and "generating substantial revenue" for funding power projects. • However, the government stated that the Act had "failed to realise the desired objectives and there were also reports of misuse of some its provisions" due to allegations of corruption and an alleged failure to deliver the benefits it had been envisaged for. What is the Roshni Act? • The land-related law, popularly known as the Roshni Act, was brought into force by the Farooq Adbullah government in 2001. • The law aimed to grant ownership rights of public land to occupants. • Reportedly, 15.85 percent of the occupied land was approved for transfer of ownership rights. • The Act also sought the conferment of proprietary rights of around 20.55 lakh kanals of land (1, 2, 50 hectares) to the occupants. • Additionally, legislators hoped the Act would help generate resources to finance power projects. • Farmers who had been occupying State land were also given ownership rights for agricultural use. • The law initially set 1990 as the cut-off year for encroachment on State land, based on which ownership would be granted. -

Annual Report 2020

Annual Report 2020 Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 OverviewAnnual of Report Tianjin Port Opportunities China’s Port Development and Challenges Industry and2020 in 2020 Port of Tianjin Section 1 Overview of China’s Port Industry and Port of Tianjin China Throughput and Trade Information Throughput at Major Ports in China China Total GDP value Million Million Tonnes RMB$Bn TEUs Total cargo dummy1 dummy2 Container 16000 300 2016 11830 218 120000 250 2017 12644 237 98652 101599 12000 100000 91928 2018 13300 250200 83204 74640 8000 2019 13951 261150 80000 2020 14549 264100 4000 60000 50 40000 0 0 20152016 201711464 2018 2019 2020 210 20000 Total cargo Container 0 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Source: Ministry of Transport of the PRC, National Bureau of Statistics Source: General Administration of Customs, PRC China Export Value China Import Value US$Bn US$Bn 2500 3000 2136 2487 2499 2590 2078 2057 2500 2263 2000 1841 2097 1587 2000 1500 1500 1000 1000 500 500 0 0 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Source: General Administration of Customs, PRC Source: General Administration of Customs, PRC 4 Overview of China’s Key Port Zones 2020 Throughput Change vs 2019 Total Cargo Container Total Cargo Container (m tonnes) (m TEU) China’s Key Port Zones Bohai Bay Tianjin 503 18.4 2.2% 6.1% Dalian 334 5.1 -8.8% -41.7% Tangshan* 703 3.1 7.0% 5.8% Qingdao 605 22.0 4.7% 4.7% Yangtze River Delta Ningbo-Zhoushan 1172 28.7 4.7% 4.3% Shanghai 711 43.5 -0.8% 0.4% Bohai Bay Suzhou 554 6.3 6.0% 0.3% Yangtze River Delta Southeast Coastline Pearl River Delta -

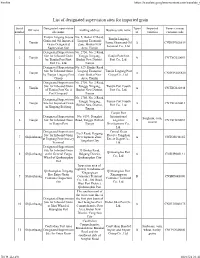

List of Designated Supervision Sites for Imported Grain

Firefox https://translate.googleusercontent.com/translate_f List of designated supervision sites for imported grain Serial Designated supervision Types Imported Venue (venue) Off zone mailing address Business unit name number site name of varieties customs code Tianjin Lingang Jiayue No. 5, Bohai 37 Road, Tianjin Lingang Grain and Oil Imported Lingang Economic 1 Tianjin Jiayue Grain and Oil A CNDGN02S619 Grain Designated Zone, Binhai New Terminal Co., Ltd. Supervision Site Area, Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Site for Inbound Grain Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port First 2 Tianjin A CNTXG020051 by Tianjin Port First Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. Port Co., Ltd. Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 529, Hunhe Road, Site for Inbound Grain Lingang Economic Tianjin Lingang Port 3 Tianjin A CNDGN02S620 by Tianjin Lingang Port Zone, Binhai New Group Co., Ltd. Group Area, Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Site for Inbound Grain Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port Fourth 4 Tianjin A CNTXG020448 of Tianjin Port No. 4 Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. Port Company Tianjin No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Designated Supervision Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port Fourth 5 Tianjin Site for Imported Grain A CNTXG020413 Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. in Xingang Beijiang Tianjin Tianjin Port Designated Supervision No. 6199, Donghai International Sorghum, corn, 6 Tianjin Site for Inbound Grain Road, Tanggu District, Logistics B CNTXG020051 sesame in Tianjin Port Tianjin Development Co., Ltd. Designated Supervision Central Grain No.9 Road, Haigang Site for Inbound Grain Reserve Tangshan 7 Shijiazhuang Development Zone, A CNTGS040165 at Jingtang Port Grocery Direct Depot Co., Tangshan City Terminal Ltd. -

PM Takes Stock of Safety Measures at Schools QNA — DOHA

www.thepeninsula.qa Friday 4 September 2020 Volume 25 | Number 8370 16 Muharram - 1442 2 Riyals BUSINESS | 11 SPORT | 16 EU finance ministers QFA, SC and will discuss recovery, Concacaf joint revenues at Berlin announce new meeting: Scholz partnership Choose the network of heroes Enjoy the Internet PM takes stock of safety measures at schools QNA — DOHA Prime Minister and Minister of Interior H E Sheikh Khalid bin Khalifa bin Abdulaziz Al Thani We congratulate our children for their return to schools visited three schools yesterday despite the exceptional circumstances created by COVID-19 morning, which included Omar pandemic after the state has taken all safety measures for bin Al Khattab Independent students, teaching staff and administration in all schools Preparatory School for Boys, operating in Qatar. With perseverance and cooperation of Al Bayan Second Primary everyone, we will overcome the challenges and it will be a School for Girls, and Qatar successful academic year, if Allah willing. Science and Technology Secondary School for Boys, to inspect the procedures and H E the Prime Minister was briefed on the various precautionary measures taken educational equipment and health preparations by the Ministry of Education made for the new academic year in light of the and Higher Education and the Ministry of Public Health to pandemic. achieve maximum safety for school students, and the H E the Prime Minister also attended a part of the teaching and administrative staff of schools, to prevent the lessons and exchanged discussions with students coronavirus (COVID-19) about their study experience. pandemic. During the visit, H E the Prime Minister was briefed on H E the Prime Minister praised the efforts of the the various educational education sector to continue distance learning equipment and health prepa- during the COVID-19 pandemic and to enhance the rations made for the new aca- utilization of technological progress in this field. -

Key Foreign Investment Projects in Qinhuangdao

KEY FOREIGN INVESTMENT PROJECTS IN QINHUANGDAO 1 CONTENTS Qinhuangdao Economic and Technological Development Zone Annual Output of 2MW Offshore Wind Machine Project................................................................................................. 1 Shanhaiguan Port-related Economic Development Zone Railway Parts Industrial Park...........3 Beijing Ruisifu New and High-Tech Co., Ltd. Rail Transportation Industry Base................. 4 Tenneco (Beijing) Automotive Shock Absorber Co., Ltd. Compact Automobile Shock Absorber Project with Annual Output of Five Million............................................................... 6 Changli County Fur Industrial Park Standardized Parts Plant for Industrial Sewing Machines..........................................................8 Qinhuangdao Zhifang Science and Technology Co., Ltd. Industrial Robot Project with Annual Output of 1000 sets................................................................................................................... 10 Beijing Capital Agribusiness & Food Group Co., Ltd. Science and Technological Industrial Park for Chinese Time-Honored Brands...................................................................................12 Sichuan Baijia Food Co., LtdHealthy Food Processing Base...................................................14 Qinglong Manchu Autonomous County Edible Mushroom Planting and Deep-Processing Project........................................................16 Shanhaiguan Port-related Economic Development ZoneFood Industry Project..................... -

4 Sept-2020.Qxd

C M C M Y B Y B RNI No: JKENG/2012/47637 Email: [email protected] POSTAL REGD NO- JK/485/2016-18 Internet Edition www.truthprevail.com Truth Prevail Epaper: epaper.truthprevail.com Vinesh Phogat recovers from COVID-19, tests negative twice 3 5 12 Union Secretary RDD e-reviews progress Mayor, team inaugurates open gym 'Government is committed to inclusive socio- under TAD Programme in Baramulla at Gangyal area economic development of J&K', Lt Governor VOL: 9 Issue: 216 JAMMU AND KASHMIR, FRIDAy , SEPTEMBER 04, 2020 DAILy PAGES 12 Rs. 2/- IInnssiiddee India's armed forces capable of dealing with Border situation in Ladakh ‘direct result’ of Chinese Security force action to effect unilateral change in status quo: MEA launch CASO in New Delhi : India on military movements" to "uni - attempts, the Indian Army has south Kashmir Chinese actions in best suitable ways : Rawat Thursday said the situation laterally" change the status strengthened its presence in at Srinagar, Sep 3 : New Delhi : India's armed capable of handling these in and Kashmir, attempted to Defence Staff Gen Bipin witnessed in the border areas quo on the southern bank of least three strategic heights in Security forces on Thursday forces are capable of handling the best suitable ways," Gen spread terrorism in other parts Rawat said on Thursday. His in eastern Ladakh over the Pangong lake in eastern the southern bank of Pangong launched a Cordon and aggressive Chinese actions in Rawat said at the online of the country. remarks came against the past four months is a "direct Ladakh on the intervening lake. -

Interview with Professor Ezra F. Vogel by KAY LU

Interview with Professor Ezra F. Vogel By KAY LU http://cnpolitics.org Ezra F. Vogel is the Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences Emeritus at Harvard University and has written on Japan, China, and Asia generally. He published the best-selling book Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China in 2011 and its Mainland Chinese version in early 2013. Q: You said in the biography that Deng “would undoubtedly have taken pride in his role in creating and implementing the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ policy.” What does “One Country, Two System” mean in current context? How has its meaning evolved over the course of the thirty years? A: The meaning is really from a broad perspective, that Hong Kong could keep very much of its own system for about fifty years (he [Deng] did not say 50 years precisely, maybe longer), including [its] capitalist system, all the foreign companies, all its way of doing things, and its Legislative Council. They even allow foreigners to keep a job in the government. The governors will be from Hong Kong. He thought that over the years, perhaps both the mainland and Hong Kong will change, and at that time, it will be easier for Hong Kong to become a part [of China]. When Thatcher went to Beijing in 1982, she really wanted Hong Kong to keep British administrators after 1997 when china resumed sovereignty. Deng did not want British officials governing Hong Kong, but Deng agreed that the rulers of Hong Kong would be local people, not mainlanders. And the current situation is something that Deng did not foresee at that time.