Full Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series A.P. Bio Handcuffed May 16, 2019 Jack agrees to help Mary dump her boyfriend and finds the task much harder than expected, meanwhile Principal Durbin enlists Anthony to do his dirty work. Jennifer Arnold, Directed by A.P. Bio Nuns March 14, 2019 As the newly-minted Driver's Ed teacher, Jack sets out to get revenge on his mother's church when he discovers the last of her money was used to buy a statue of the Virgin Mary. Lynn Shelton, Directed by A.P. Bio Spectacle May 30, 2019 After his computer breaks, Jack rallies his class to win the annual Whitlock's Got Talent competition so the prize money can go towards a new laptop. Helen and Durbin put on their best tuxes to host while Mary, Stef and Michelle prepare a hand-bell routine. Carrie Brownstein, Directed by Abby's The Fish May 31, 2019 When Bill admits to the group that he has Padres season tickets behind home plate that he lost in his divorce, the gang forces him to invite his ex-wife to the bar to reclaim the tickets. Betsy Thomas, Directed by After Life Episode 2 March 08, 2019 Thinking he has nothing to lose, Tony contemplates trying heroin. He babysits his nephew and starts to bond -- just a bit -- with Sandy. Ricky Gervais, Directed by Alexa & Katie The Ghost Of Cancer Past December 26, 2018 Alexa's working overtime to keep Christmas on track. But finding her old hospital bag stirs up memories that throw her off her holiday game. -

CITY of ANGELS Book by Larry Gelbart | Music by Cy Coleman | Lyrics by David Zippel Hits the West End!

PRESS RELEASE: 19 December 2019 The Donmar Warehouse’s Olivier Award-winning production of CITY OF ANGELS Book by Larry Gelbart | Music by Cy Coleman | Lyrics by David Zippel Hits the West End! Josie Rourke’s critically acclaimed and Olivier Award winning production of City of Angels makes its West End transfer six years since opening at the Donmar Warehouse in 2014. The musical will play at the Garrick Theatre for a limited season, opening on Tuesday 24 March 2020 with previews from Thursday 5 March 2020, reuniting the production’s entire creative team. The West End production will star Hadley Fraser (Les Misérables, Young Frankenstein), Theo James (Divergent series), Rosalie Craig (Company), Rebecca Trehearn (Show Boat), Jonathan Slinger (various roles with the RSC) with BRIT Award winner Nicola Roberts (Girls Aloud) making her stage debut and Emmy and Grammy Award nominee Vanessa Williams (Ugly Betty, Desperate Housewives) making her West End debut. The cast also includes Marc Elliott, Emily Mae, Cindy Beliot, Michelle Bishop, Nick Cavaliere, Rob Houchen, Manuel Pacific, Mark Penfold, Ryan Reid, Joshua St Clair & Sadie-Jean Shirley. A screenwriter with a movie to finish. A private eye with a case to crack. But nothing’s black and white when a dame is involved. And does anyone stick to the script in this city? This is Tinseltown. You gotta ask yourself: what’s real…and what’s reel… Josie Rourke’s “ingenious, stupendous revival” (The Telegraph) premiered in 2014, when it was hailed as “a blissful evening” (The Stage) that’s “smart, seductive and very funny” (Evening Standard). -

Master Streaming List 06112021

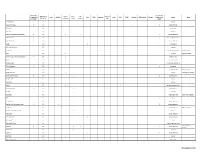

Heat Index Personal Star Prime IMDb Rating Netflix PBS Peacock/ 5=Intense/Dark Rating 1 to 5 Acorn Brit Box Video/IMDB Hulu HBO ROKU (Out of 10) Streaming Passport NBC Genre Notes 1="Cozie" (best) TV 19-2 8.2 policing A Confession 7.5 police detective A French Village 8.3 drama A Touch of Cloth 8.0 police detective A Touch of Frost 2 7.9 4 police detective Above Suspicion 2 7.1 3 police detective Absentia 7.3 mystery Acceptable Risk 6.7 general mystery/crime Accused 8.0 legal drama Agatha and the Midnight Murders 5.6 mystery Agatha and the Truth of Murder 6.3 mystery Agatha Christie Miss Marple 1 7.7 3 citizen sleuth Agatha Christie's Partners in Crime 2 7.6 4 private detective (Original Series) Agatha Raisin 1 7.4 2 citizen sleuth Alias Grace 7.7 psychological drama Alibi 7.4 general mystery/crime All Creatures Great & Small (1978) 1 8.3 drama All Creatures Great & Small (2020) 1 8.4 drama Alone in Berlin 6.5 espionage/terrorism/political Amber 6.1 general mystery/crime Amnesia 2 7.2 4 mystery An Inspector Calls 1 7.7 2 police detective And Then There Were None 8.0 general mystery/crime Another Life 6.5 general mystery/crime Armadillo 6.7 police detective Arthur & George 1 7.1 3 general mystery/crime Atlantic Crossing 7.1 WW II Drama Ava 5.4 thriller Babylon Berlin 8.4 police detective English subtitles Backstrom 6.7 police detective English subtitles Bad Blood 7.3 heists/organized crme Ballykissangel 1 7.5 4 drama Balthazar 7.5 forensic mystery English subtitles Bang 6.4 drama Banshee 8.4 general mystery/crime last updated: 8/17/21 -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Writing For A Comedy Series A.P. Bio Sweet Low Road April 25, 2019 When budget cuts threaten to gut Whitlock and put his job in jeopardy, Jack recruits Mary, Stef, and Michelle to take down the Superintendent. Durbin plans an appeal to the heart, while the students plan an appeal to the soul. A.P. Bio Wednesday Morning, 8AM March 21, 2019 In the hectic thirty minutes that start every day at Whitlock, Jack tries to retrieve his massage chair from Whitlock's intriguing payroll accountant, Lynette. Durbin and Helen prepare for the morning announcements, Michelle gives a eulogy, and Mary and Stef fix an art emergency. Abby's Pilot March 28, 2019 Abby's unlicensed backyard bar hits a major snag when new landlord Bill, who recently inherited the house from his deceased aunt, shows up and proposes major changes. Abby's Rule Change April 04, 2019 Abby and Bill clash when he proposes a change to one of the coveted bar rules. Facing an impasse, the two appeal to the bar regulars to help settle their dispute. After Life Episode 1 March 08, 2019 Tony's cantankerous funk -- which he calls a superpower -- is taking a toll on his co-workers. Meanwhile, a new writer starts at The Tambury Gazette. Alexa & Katie The Ghost Of Cancer Past December 26, 2018 Alexa's working overtime to keep Christmas on track. But finding her old hospital bag stirs up memories that throw her off her holiday game. American Housewife Body Image October 31, 2018 After the previous "Fattest Housewife in Westport" gets plastic surgery, Chloe Brown Mueller publicity makes fun of Katie's weight now that she's inherited that title. -

An Honor Roll Containing a Pictorial Record of the Gallant And

9Ao9/onoP 9^oIl £3 ***< 1917- 1918- 1919 5ll^€»C€~ ))OOOllQ PUBLISHED BY The Leader Publishing Company Pipestone, Minnesota Off PubBeher KAY 9 1912 7/zei/Socved to /ceep t/ie/Jrfzf/ori General John J. Pershing County's Honored Dead RUDOLPH T. BARTELT, Luverne, Minn. Private, 77th Div. Entered ser- vice May, 1918 Trained at Camp Lewis, Wash. Departed overseas August, 1918. Battle, Argoune. Died of wounds in France. ROBERT BLACKWOOD, Luverne, Minn. Private, Co. "K," 308th Inf. En- tered service May 27, 1918. Trained at Camp Lewis, Wash. Departed overseas August, 1918. Battle, Argonne. Died of pneumonia, Base Hospital No. 27, France, Dec. 9, 1918. HARRY BACHTELL, Luverne, Minn. Private, Co. "F," 136th Inf., 34tliDiv. Entered service June 26, 1917. Trained at Camp Cody, N. Mex. Died January, 1918 at Camp Cody of pneumonia. No photograph available. Rock County's Honored Dead KELLY BOOMGARDEN, Steen Minn. 111th Inf., Co. "E." Entered ser- vice May 27, 1918. Trained at Camp Kearney, Calif., Camp Lewis, Camp Mills. Departed overseas (date not known). Battle. Ar- gonne. Killed in action Sept. 29, 1918, Argonne Forest. VICTOR I. CLOCK, Hills, Minn. Private, Const. Co. 14, Air Service. Entered service May 17, 1918. Trained at Ford Junction, Sussex, Eng. Departed overseas August 8, 1918. Died, Portsmouth, Eng., influenza, Oct. 26, 1918. Rock County's Honored Dead ELMEE J. DELL, Harchviek, Minn. Private, Co. "A," 165th Inf., 42nd Div. Entered service July 15, 1917. Trained at Camp Cody, N. Mex. Departed overseas June 26, 1918. Battles: Chateau Thierry, St. Mihiel, Argonne. Missing in action Oct. -

Here the Travel Bookshop on Blenheim the Knack and How to Duffer Joseph Despins/William the Bramley Arms

SICKBOY www.portobellofilmfestival.com Hollywood W11 / W10 by Tom Vague Bedknobs and A Hard Day’s Night Leo the Last John Boorman Breaking Glass Brian Gibson Parting Shots Michael Winner Broomsticks Robert Stevenson Richard Lester 1964 Ringo Starr runs 1970 Marcello Mastroianni brings about 1980 Dodi Fayed produced new wave 1998 Chris Rea on Bramley Road. 1971 set in 1940 Disneyland Portobello into a shop on the corner of All Saints a ‘firework revolution’, in which his film in which skinheads attack a march Sliding Doors Peter Howitt market scene featuring a proto-Carnival and Lancaster Road. Then all the house on the site of Lancaster West under the Westway roundabout. 1998 Gwyneth Paltrow at the Mangrove song and dance routine. Beatles run in and out of the police Estate is destroyed. The Final Conflict Graham on All Saints Road (then Mas Café). station (the old St John's church school) Withnail and I Baker 1981 The Omen 3 film featuring on Walmer Rd. Twice Upon a Bruce Robinson 1987 set in 1969 the most notorious local horror scene, Yesterday Maria Ripoli 1998 The Nanny Seth Holt 1965 Richard E Grant and Paul McGann are in which the pram goes down the hill Douglas Henshall meets Lena Headey Bette Davis on Latimer Road in 1964 chased out of the Tavistock pub on and is hit by a taxi on Lansdowne Rd. on All Saints. before the area was demolished to Tavistock Crescent. Their house is off Betrayal David Jones 1982 Notting Hill Roger Michell 1999 make way for the Westway roundabout. -

An Honor Roll Containing a Pictorial Record of the Gallant And

wmM, f J ,' Jl I f \ / ! ,7 .^ 1 ( l&^fiiBAiaB^v y/zp/zSorvoc/ fo AoGp t/ie/paf/on 9/„.'-%„or9?o/? s\ 1917'" 1918- 1919 [o '^CxCC ))ooo o PUBLISHED BY The Leader Publishing Company Pipestone, Minni^sota 1^ ^ HAY J* I9M ^ 1 A =_>< .25 Pipestone County^s Honored Dead PDiss ! CARI^ETON ASHTON — Pipe- m stone, Minn. Private, ist Co., ml Coast Defense Artillery. Entered service dis- I SSI November 30, 1914; cliarg^ed 191 7 because of physical disability. Died March 7, 1919. im\ PETER BARKER — Holland, Minn. Private, Infantry. En- tered service Oct. 23, 191 8; train- ed at Camp Cody, N. M. Died November 3, 1918, at Camp Cody, N. M., of influenza. I I! I li WALTER EDWARD BREI- IIOLZ—Holland, Minn. Pri- vate, Co. M, 53rd Inf. Entered service May i, 1918; trained at Camp W'adsworth, S. C. ; depart- ed overseas July, 1918; battles, Meuse and Argonne. Died De- cember 18, 1918, at Recy-Sur- Oise, France, peritonitis. '"^-"':g^MlMMlii^ili1 ; aummmiii fail Pipestone County's Honored Dead Hill IRVING BENJAMIN ENGEL- BART—Pipestone, Minn. Cor- poral, Co. B, 119th Inf. Entered service Feb. 28, 1918; trained at Camp Dodge ; departed overseas May 15, 1918. Killed in action September 29, 191 8. .:;ii VICTOR ELMER IIURD—Re- gina, Canada. Private, Infantrj'. Entered service Jnly, 1918; train- ed at Cam]:) Wadsvvorth, S. C. departed overseas Sept., 1918. Died October 10, 1918. in France, of pnenmonia. OLIVER SMITH HUVCK—Jas- per, Minn. Seaman, second class, U. S. S. Transport Bridgeport. Entered service Ma\', 1917; train- ed at Great Lakes Naval Train- ing Station. -

Talking Book Topics January-Februrary 2019

Talking Book Topics January–February 2019 Volume 85, Number 1 Need help? Your local cooperating library is always the place to start. For general information and to order books, call 1-888-NLS-READ (1-888-657-7323) to be connected to your local cooperating library. To find your library, visit www.loc.gov/nls and select “Find Your Library.” To change your Talking Book Topics subscription, contact your local cooperating library. Get books fast from BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site. To use BARD, contact your local cooperating library or visit nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. The free BARD Mobile app is available from the App Store, Google Play, and Amazon’s Appstore. About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics, published in audio, large print, and online, is distributed free to people unable to read regular print and is available in an abridged form in braille. Talking Book Topics lists titles recently added to the NLS collection. The entire collection, with hundreds of thousands of titles, is available at www.loc.gov/nls. Select “Catalog Search” to view the collection. Talking Book Topics is also online at www.loc.gov/nls/tbt and in downloadable audio files from BARD. Overseas Service American citizens living abroad may enroll and request delivery to foreign addresses by contacting the NLS Overseas Librarian by phone at (202) 707-9261 or by email at [email protected]. Page 1 of 109 Music scores and instructional materials NLS music patrons can receive braille and large-print music scores and instructional recordings through the NLS Music Section. -

Master Streaming List 08162020

Heat Index Personal Star IMDb Rating Netflix Prime PBS Peacock/ 5=Intense/Dar Acorn Brit Box Hulu HBO Sundance Starz SHO ROKU Cinemax BBC America Disney+ Rating 1 to 5 Genre Notes (Out of 10) Streaming Video Passport NBC k 1="Cozie" (best) Breaking Bad 5 9.5 1 5 drama Game of Thrones 5 9.5 1 5 action/thriller Chernobyl 9.4 1 docudrama The Wire 9.3 1 policing Sherlock (Benedict Cumberbatch) 3 9.2 1 1 4 private detective The Sopranos 5 9.2 1 5 heists/organized crme True Detective 5 9.0 1 5 police detective Fargo 8.9 1 crime drama Only Fools & Horses 8.9 1 comedy Aranyelet 8.8 1 general mystery/crime English subtitles Dark 8.8 1 mystery English subtitles House of Cards (Netflix production) 4 8.8 1 political satire Narcos 8.8 1 organized crime Peaky Blinders 8.8 1 heists/organized crime The Sandbaggers 3 8.8 1 4 espionage Umbre 8.8 1 organized crime English subtitles Better Call Saul 8.7 1 drama Breaking Bad prequel Brideshead Revisited 2 8.7 1 1 5 period drama Danger UXB 8.7 1 drama Deadwood 8.7 1 drama Dexter 8.7 1 1 general mystery/crime Downton Abbey 1 8.7 1 1 period drama Fleabag 8.7 1 comedy Gomorrah 8.7 1 organized crime Italian with subtitles Rake 8.7 1 2 legal Sacred Games 8.7 1 police detective Sherlock Holmes (Jeremy Brett) 2 8.7 1 5 private detective The Bureau 8.7 1 police detective English subtitles The Marvelous Mrs. -

Series List 2021-05-15

Series List Action (74) A Simple Murder Airwolf Alex Rider Almost Human American Odyssey Angel Arrow Birds of Prey Blade: The Series Blindspot Blood & Treasure Blood Drive Blue Thunder Chicago Fire Cobra Kai Condor Crackdown Curfew Deadly Class Deep State Die Hart Dominion Flashpoint Generation Kill Hawaii Five-0 Helstrom Kung Fu L.A.'s Finest Lethal Weapon Lost MacGyver Magnum P.I. Magnum, P.I. Marvel's Iron Fist Miami Vice Most Dangerous Game NCIS: Los Angeles Naxalbari Nikita Person of Interest Power Rangers Beast Professionals Revolution Rome S.W.A.T. Morphers SEAL Team SIX Shooter Shrikant Bashir Spartacus Spartacus: Gods of the Arena Spooks Taken Teen Wolf The A-Team The Fugitive The Gifted The Incredible Hulk The Last Kingdom The Librarians The Long Road Home The Musketeers The Pacific The Passage The Unit Timeless Torchwood Transporter: The Series Treadstone Walker Watchmen Whiskey Cavalier Wynonna Earp Your Honor Animation (96) Adventure Time: Distant Adventure Time American Dad! Animaniacs Apple & Onion Lands Barbie: Life In The Archer Be Cool, Scooby-Doo! Ben 10 Ben 10 Reboot Dreamhouse Ben 10: Alien Force Ben 10: Omniverse Ben 10: Ultimate Alien Ben and Holly's Little Kingdom Bless the Harts Bob's Burgers Brickleberry Chop Socky Chooks Clarence Close Enough Corner Gas Animated Counterfeit Cat Courage The Cowardly Dog Crossing Swords DC Super Hero Girls Foster's Home For Imaginary Dicktown Dragon Ball Super Duncanville Final Space Friends He-Man and the Masters of Jayce and the Wheeled Freedom Fighters: The Ray Harley Quinn -

British Writers, Including Virginia Woolf, E

Society of Young Nigerian Writers Richard Adams Richard Adams, born in 1920, British writer of fiction and folktales for both adults and children. His best-known work is the novel Watership Down (1972; film version 1978), for which he received the Carnegie Medal (1972) and the Guardian Award (1973). This story about a community of rabbits and its search for a new warren is memorable for the power of its narration and its detailed, knowledgeable descriptions of the countryside and wildlife. The novel has also been interpreted as a political allegory offering a parallel between the various warrens that the rabbits visit and different systems of government and their effects. Richard George Adams was born in Newbury, Berkshire, England, and educated at Worcester College, University of Oxford, where he studied modern history and received his master of arts degree in 1948. Adams spent the years from 1940 to 1946 in the British army, serving during World War II (1939-1945). Prior to becoming a full-time writer, he was a successful civil servant from 1948 to 1974. Adams is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and the Royal Society of Arts. His other works include Shardik (1974) and Maia (1984), both set in the imaginary Beklan Empire; The Plague Dogs (1977), written in a similar vein to Watership Down; The Girl in a Swing (1980), one of his few works with a human main character; Traveller (1988), which recounts the events of the American Civil War (1861-1865) from the perspective of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's horse; and a collection of folktales, The Iron Wolf and Other Stories (1980). -

An Overview of the Film, Television, Video and Dvd Industries In

the STATS an overview of the film, television, video and DVD industries 1990 - 2003 contents THIS PDF IS FULLY NAVIGABLE BY USING THE “BOOKMARKS” FACILITY IN ADOBE ACROBAT READER Introduction by David Sharp . i Introduction to 1st edition (2003) by Ray Templeton . .ii Preface by Philip Wickham . .iii the STATS 1990 . .1 1991 . .14 1992 . 32 1993 . 54 1994 . .74 1995 . .92 1996 . .112 1997 . .136 1998 . .163 1999 . .188 2000 . .220 2001 . .251 2002 . .282 2003 . .310 Cumulative Tables . .341 Country Codes . .351 Bibliography . .352 Research: Erinna Mettler/Philip Wickham Design/Tabulation: Ian O’Sullivan Additional Research: Matt Ker Elena Marcarini Bibliography: Elena Marcarini © 2006 BFI INFORMATION SERVICES BFI NATIONAL LIBRARY 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN ISBN: 1-84457-017-7 Phil Wickham is an Information Officer in the Information Services Unit of the BFI National Library. He writes and lectures extensively on British film and television. Erinna Mettler is an Information Officer in the Information Services Unit of the National Library and has contributed to numerous publications. Ian O’Sullivan is also an Information Officer in the Information Services Unit of the BFI National Library and has designed a number of publications for the BFI. Information Services BFI National Library British Film Institute 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN Tel: + 44 (0) 20 7255 1444 Fax: + 44 (0) 20 7436 0165 Contact us at www.bfi.org.uk/ask with your film and television enquiries. Alternatively, telephone +44 (0) 20 7255 1444 and ask for Information (Mon-Fri: 10am-1pm & 2-5pm) Try the BFI website for film and television information 24 hours a day, 52 weeks a year… Film & TV Info – www.bfi.org.uk/filmtvinfo - contains a range of information to help find answers to your queries.