Development and Validation of a New Technique for Estimating a Minimum Postmortem Interval Using Adult Blow Fly (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Carcass Attendance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Arthropods and Corpses

Arthropods and Corpses 207 10 Arthropods and Corpses Mark Benecke, PhD CONTENTS INTRODUCTION HISTORY AND EARLY CASEWORK WOUND ARTIFACTS AND UNUSUAL FINDINGS EXEMPLARY CASES: NEGLECT OF ELDERLY PERSONS AND CHILDREN COLLECTION OF ARTHROPOD EVIDENCE DNA FORENSIC ENTOMOTOXICOLOGY FURTHER ARTIFACTS CAUSED BY ARTHROPODS REFERENCES SUMMARY The determination of the colonization interval of a corpse (“postmortem interval”) has been the major topic of forensic entomologists since the 19th century. The method is based on the link of developmental stages of arthropods, especially of blowfly larvae, to their age. The major advantage against the standard methods for the determination of the early postmortem interval (by the classical forensic pathological methods such as body temperature, post- mortem lividity and rigidity, and chemical investigations) is that arthropods can represent an accurate measure even in later stages of the postmortem in- terval when the classical forensic pathological methods fail. Apart from esti- mating the colonization interval, there are numerous other ways to use From: Forensic Pathology Reviews, Vol. 2 Edited by: M. Tsokos © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ 207 208 Benecke arthropods as forensic evidence. Recently, artifacts produced by arthropods as well as the proof of neglect of elderly persons and children have become a special focus of interest. This chapter deals with the broad range of possible applications of entomology, including case examples and practical guidelines that relate to history, classical applications, DNA typing, blood-spatter arti- facts, estimation of the postmortem interval, cases of neglect, and entomotoxicology. Special reference is given to different arthropod species as an investigative and criminalistic tool. Key Words: Arthropod evidence; forensic science; blowflies; beetles; colonization interval; postmortem interval; neglect of the elderly; neglect of children; decomposition; DNA typing; entomotoxicology. -

Use of Necrophagous Insects As Evidence of Cadaver Relocation

A peer-reviewed version of this preprint was published in PeerJ on 1 August 2017. View the peer-reviewed version (peerj.com/articles/3506), which is the preferred citable publication unless you specifically need to cite this preprint. Charabidze D, Gosselin M, Hedouin V. 2017. Use of necrophagous insects as evidence of cadaver relocation: myth or reality? PeerJ 5:e3506 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3506 Use of necrophagous insects as evidence of cadaver relocation: myth or reality? Damien CHARABIDZE Corresp., 1 , Matthias GOSSELIN 2 , Valéry HEDOUIN 1 1 CHU Lille, EA 7367 - UTML - Unite de Taphonomie Medico-Legale, Univ Lille, 59000 Lille, France 2 Research Institute of Biosciences, Laboratory of Zoology, UMONS - Université de Mons, Mons, Belgium Corresponding Author: Damien CHARABIDZE Email address: [email protected] The use of insects as indicators of postmortem displacement is discussed in many text, courses and TV shows, and several studies addressing this issue have been published. However, the concept is widely cited but poorly understood, and only a few forensic cases have successfully applied such a method. Surprisingly, this question has never be taken into account entirely as a cross-disciplinary theme. The use of necrophagous insects as evidence of cadaver relocation actually involves a wide range of data on their biology: distribution areas, microhabitats, phenology, behavioral ecology and molecular analysis are among the research areas linked to this problem. This article reviews for the first time the current knowledge on these questions and analysze the possibilities/limitations of each method to evaluate their feasibility. This analysis reveals numerous weaknesses and mistaken beliefs but also many concrete possibilities and research opportunities. -

Midsouth Entomologist 5: 39-53 ISSN: 1936-6019

Midsouth Entomologist 5: 39-53 ISSN: 1936-6019 www.midsouthentomologist.org.msstate.edu Research Article Insect Succession on Pig Carrion in North-Central Mississippi J. Goddard,1* D. Fleming,2 J. L. Seltzer,3 S. Anderson,4 C. Chesnut,5 M. Cook,6 E. L. Davis,7 B. Lyle,8 S. Miller,9 E.A. Sansevere,10 and W. Schubert11 1Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology, and Plant Pathology, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS 39762, e-mail: [email protected] 2-11Students of EPP 4990/6990, “Forensic Entomology,” Mississippi State University, Spring 2012. 2272 Pellum Rd., Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 33636 Blackjack Rd., Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 4673 Conehatta St., Marion, MS 39342, [email protected] 52358 Hwy 182 West, Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 6101 Sandalwood Dr., Madison, MS 39110, [email protected] 72809 Hwy 80 East, Vicksburg, MS 39180, [email protected] 850102 Jonesboro Rd., Aberdeen, MS 39730, [email protected] 91067 Old West Point Rd., Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 10559 Sabine St., Memphis, TN 38117, [email protected] 11221 Oakwood Dr., Byhalia, MS 38611, [email protected] Received: 17-V-2012 Accepted: 16-VII-2012 Abstract: A freshly-euthanized 90 kg Yucatan mini pig, Sus scrofa domesticus, was placed outdoors on 21March 2012, at the Mississippi State University South Farm and two teams of students from the Forensic Entomology class were assigned to take daily (weekends excluded) environmental measurements and insect collections at each stage of decomposition until the end of the semester (42 days). Assessment of data from the pig revealed a successional pattern similar to that previously published – fresh, bloat, active decay, and advanced decay stages (the pig specimen never fully entered a dry stage before the semester ended). -

Enhancing Forensic Entomology Applications: Identification and Ecology

Enhancing forensic entomology applications: identification and ecology A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Sarah Victoria Louise Langer 2017 Environmental and Life Sciences M.Sc. Graduate Program September 2017 ABSTRACT Enhancing forensic entomology applications: identification and ecology Sarah Victoria Louise Langer The purpose of this thesis is to enhance forensic entomology applications through identifications and ecological research with samples collected in collaboration with the OPP and RCMP across Canada. For this, we focus on blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and present data collected from 2011-2013 from different terrestrial habitats to analyze morphology and species composition. Specifically, these data were used to: 1) enhance and simplify morphological identifications of two commonly caught forensically relevant species; Phormia regina and Protophormia terraenovae, using their frons-width to head- width ratio as an additional identifying feature where we found distinct measurements between species, and 2) to assess habitat specificity for urban and rural landscapes, and the scale of influence on species composition when comparing urban and rural habitats across all locations surveyed where we found an effect of urban habitat on blow fly species composition. These data help refine current forensic entomology applications by adding to the growing knowledge of distinguishing morphological features, and our understanding of habitat use by Canada’s blow fly species which may be used by other researchers or forensic practitioners. Keywords: Calliphoridae, Canada, Forensic Science, Morphology, Cytochrome Oxidase I, Distribution, Urban, Ecology, Entomology, Forensic Entomology ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Blow flies are among the most familiar of insects. -

Terry Whitworth 3707 96Th ST E, Tacoma, WA 98446

Terry Whitworth 3707 96th ST E, Tacoma, WA 98446 Washington State University E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Published in Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington Vol. 108 (3), 2006, pp 689–725 Websites blowflies.net and birdblowfly.com KEYS TO THE GENERA AND SPECIES OF BLOW FLIES (DIPTERA: CALLIPHORIDAE) OF AMERICA, NORTH OF MEXICO UPDATES AND EDITS AS OF SPRING 2017 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 Materials and Methods ................................................................................................... 5 Separating families ....................................................................................................... 10 Key to subfamilies and genera of Calliphoridae ........................................................... 13 See Table 1 for page number for each species Table 1. Species in order they are discussed and comparison of names used in the current paper with names used by Hall (1948). Whitworth (2006) Hall (1948) Page Number Calliphorinae (18 species) .......................................................................................... 16 Bellardia bayeri Onesia townsendi ................................................... 18 Bellardia vulgaris Onesia bisetosa ..................................................... -

Forensic Entomology: the Use of Insects in the Investigation of Homicide and Untimely Death Q

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. Winter 1989 41 Forensic Entomology: The Use of Insects in the Investigation of Homicide and Untimely Death by Wayne D. Lord, Ph.D. and William C. Rodriguez, Ill, Ph.D. reportedly been living in and frequenting the area for several Editor’s Note weeks. The young lady had been reported missing by her brother approximately four days prior to discovery of her Special Agent Lord is body. currently assigned to the An investigation conducted by federal, state and local Hartford, Connecticut Resident authorities revealed that she had last been seen alive on the Agency ofthe FBi’s New Haven morning of May 31, 1984, in the company of a 30-year-old Division. A graduate of the army sergeant, who became the primary suspect. While Univercities of Delaware and considerable circumstantial evidence supported the evidence New Hampshin?, Mr Lordhas that the victim had been murdered by the sergeant, an degrees in biology, earned accurate estimation of the victim’s time of death was crucial entomology and zoology. He to establishing a link between the suspect and the victim formerly served in the United at the time of her demise. States Air Force at the Walter Several estimates of postmortem interval were offered by Army Medical Center in Reed medical examiners and investigators. These estimates, Washington, D.C., and tire F however, were based largely on the physical appearance of Edward Hebert School of the body and the extent to which decompositional changes Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland. had occurred in various organs, and were not based on any Rodriguez currently Dr. -

Use of DNA Sequences to Identify Forensically Important Fly Species in the Coastal Region of Central California (Santa Clara County) Angela T

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Summer 2013 Use of DNA Sequences to Identify Forensically Important Fly Species in the Coastal Region of Central California (Santa Clara County) Angela T. Nakano San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Nakano, Angela T., "Use of DNA Sequences to Identify Forensically Important Fly Species in the Coastal Region of Central California (Santa Clara County)" (2013). Master's Theses. 4357. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.8rxw-2hhh https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4357 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USE OF DNA SEQUENCES TO IDENTIFY FORENSICALLY IMPORTANT FLY SPECIES IN THE COASTAL REGION OF CENTRAL CALIFORNIA (SANTA CLARA COUNTY) A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Biological Sciences San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Angela T. Nakano August 2013 ©2013 Angela T. Nakano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled USE OF DNA SEQUENCES TO IDENTIFY FORENSICALLY IMPORTANT FLY SPECIES IN THE COASTAL REGION OF CENTRAL CALIFORNIA (SANTA CLARA COUNTY) by Angela T. Nakano APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY August 2013 Dr. Jeffrey Honda Department of Biological Sciences Dr. -

First Report of Genus Cynomya Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 (Diptera: Calliphoridae) from India

ISSN 0973-1555(Print) ISSN 2348-7372(Online) HALTERES, Volume 9, 185-186, 2018 © MEENAKSHI BHARTI AND KNUT ROGNES doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1488543 Short communication First report of genus Cynomya Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 (Diptera: Calliphoridae) from India *Meenakshi Bharti1 & Knut Rognes2 1Department of Zoology and Environmental Sciences, Punjabi University, Patiala, India. 2University of Stavanger, Faculty of Arts and Education, Department of Early Childhood Education, NO–4036 Stavanger, Norway. (Email: [email protected]) Keywords: Calliphoridae, Calliphorinae, Cynomya mortuorum, new record, India, Himalaya. Received: 13 November 2018; Online: 15 November 2018. The genus Cynomya Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830, belonging in the subfamily Calliphorinae of the Calliphoridae, is represented by two World species: C. cadaverina Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 and C. mortuorum (Linnaeus, 1761). The genus is generally identified by the lack of presutural intra- alar seta and presence of 1or 2 post-acrostichal setae (Rognes, 1991). Herein, we provide the first report of Cynomya mortuorum (Linnaeus, 1761) from India (Bharti, 2011). The specimens (5 females) were collected from Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers National Park falling in the state of Uttarakhand at a height of 3500m (30.6588° N, 79.8387° E). The species in question is widely distributed in the Palaearctic Region. However, in the Nearctic Region, it occurs in Greenland and Alaska. It can be separated from the Nearctic congener Cynomya cadaverina Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 on the basis of bright yellow to orange facial membrane, anterior two thirds of gena, whole parafacial and anterior half of fronto-orbital plate (these areas black or reddish brown in C. cadaverina) and presence of one post-acrostichal seta (two in case of C. -

Bird's Nest Screwworm

Beneficial Species Profile Photo credit: Copyright © 2013 Mardon Erbland, bugguide.net Common Name: Bird’s Nest Screwworm Fly / Holarctic Blow Fly Scientific Name: Protophormia terraenovae Order and Family: Diptera / Calliphoridae Size and Appearance: Length (mm) Appearance Egg 1mm Larva/Nymph Small and white, with about 12 1-12mm segments Adult Dark anterior thoracic spiracle, dark metallic blue in color. 8-12 mm Similar to Phormia regina, however P. terraenovae has longer dorsocentral bristles with acrostichal (set in highest row) bristles short or absent. Pupa (if applicable) 8-9mm Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Sponging in adults / Mouthhooks in larvae Host/s: Larvae develop primarily in carrion. Description of Benefits (predator, parasitoid, pollinator, etc.): This insect is used in Forensic and Medical fields. Maggot Debridement Therapy is the use of maggots to clean and disinfect necrotic flesh wounds. To be usable in this practice, the creature must only target the necrotic tissues. This species ‘fits the bill.’ P. terraenovae is known to produce antibiotics as they feed, helping to fight some infections. P. terraenovae is one of the only blow fly species usable in this way. Blow flies are also one of the first species to arrive on a cadaver. Due to early arrival, they can be the most informative for postmortem investigations. Scientists will collect, note, rear, and identify the species to determine life cycles and developmental rates. Once determined, they can calculate approximate death. This species is also known to cause myiasis in livestock, causing wound strike and death. References: Species Protophormia terraenovae. (n.d.). Retrieved September 04, 2020, from https://bugguide.net/node/view/862102 Byrd, J. -

Use of DNA Sequences to Identify Forensically Important Fly Species in the Coastal Region of Central California (Santa Clara County)

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Summer 2013 Use of DNA Sequences to Identify Forensically Important Fly Species in the Coastal Region of Central California (Santa Clara County) Angela T. Nakano San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Nakano, Angela T., "Use of DNA Sequences to Identify Forensically Important Fly Species in the Coastal Region of Central California (Santa Clara County)" (2013). Master's Theses. 4357. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.8rxw-2hhh https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4357 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USE OF DNA SEQUENCES TO IDENTIFY FORENSICALLY IMPORTANT FLY SPECIES IN THE COASTAL REGION OF CENTRAL CALIFORNIA (SANTA CLARA COUNTY) A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Biological Sciences San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Angela T. Nakano August 2013 ©2013 Angela T. Nakano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled USE OF DNA SEQUENCES TO IDENTIFY FORENSICALLY IMPORTANT FLY SPECIES IN THE COASTAL REGION OF CENTRAL CALIFORNIA (SANTA CLARA COUNTY) by Angela T. Nakano APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY August 2013 Dr. Jeffrey Honda Department of Biological Sciences Dr. -

Test Key to British Blowflies (Calliphoridae) And

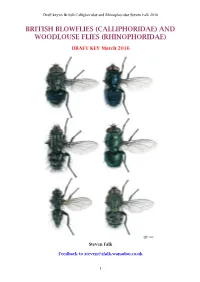

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016 BRITISH BLOWFLIES (CALLIPHORIDAE) AND WOODLOUSE FLIES (RHINOPHORIDAE) DRAFT KEY March 2016 Steven Falk Feedback to [email protected] 1 Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016 PREFACE This informal publication attempts to update the resources currently available for identifying the families Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae. Prior to this, British dipterists have struggled because unless you have a copy of the Fauna Ent. Scand. volume for blowflies (Rognes, 1991), you will have been largely reliant on Van Emden's 1954 RES Handbook, which does not include all the British species (notably the common Pollenia pediculata), has very outdated nomenclature, and very outdated classification - with several calliphorids and tachinids placed within the Rhinophoridae and Eurychaeta palpalis placed in the Sarcophagidae. As well as updating keys, I have also taken the opportunity to produce new species accounts which summarise what I know of each species and act as an invitation and challenge to others to update, correct or clarify what I have written. As a result of my recent experience of producing an attractive and fairly user-friendly new guide to British bees, I have tried to replicate that approach here, incorporating lots of photos and clear, conveniently positioned diagrams. Presentation of identification literature can have a big impact on the popularity of an insect group and the accuracy of the records that result. Calliphorids and rhinophorids are fascinating flies, sometimes of considerable economic and medicinal value and deserve to be well recorded. What is more, many gaps still remain in our knowledge. -

Key for Identification of European and Mediterranean Blowflies (Diptera, Calliphoridae) of Forensic Importance Adult Flies

Key for identification of European and Mediterranean blowflies (Diptera, Calliphoridae) of forensic importance Adult flies Krzysztof Szpila Nicolaus Copernicus University Institute of Ecology and Environmental Protection Department of Animal Ecology Key for identification of E&M blowflies, adults The list of European and Mediterranean blowflies of forensic importance Calliphora loewi Enderlein, 1903 Calliphora subalpina (Ringdahl, 1931) Calliphora vicina Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 Calliphora vomitoria (Linnaeus, 1758) Cynomya mortuorum (Linnaeus, 1761) Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann, 1819) Chrysomya marginalis (Wiedemann, 1830) Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius, 1794) Phormia regina (Meigen, 1826) Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) Lucilia ampullacea Villeneuve, 1922 Lucilia caesar (Linnaeus, 1758) Lucilia illustris (Meigen, 1826) Lucilia sericata (Meigen, 1826) Lucilia silvarum (Meigen, 1826) 2 Key for identification of E&M blowflies, adults Key 1. – stem-vein (Fig. 4) bare above . 2 – stem-vein haired above (Fig. 4) . 3 (Chrysomyinae) 2. – thorax non-metallic, dark (Figs 90-94); lower calypter with hairs above (Figs 7, 15) . 7 (Calliphorinae) – thorax bright green metallic (Figs 100-104); lower calypter bare above (Figs 8, 13, 14) . .11 (Luciliinae) 3. – genal dilation (Fig. 2) whitish or yellowish (Figs 10-11). 4 (Chrysomya spp.) – genal dilation (Fig. 2) dark (Fig. 12) . 6 4. – anterior wing margin darkened (Fig. 9), male genitalia on figs 52-55 . Chrysomya marginalis – anterior wing margin transparent (Fig. 1) . 5 5. – anterior thoracic spiracle yellow (Fig. 10), male genitalia on figs 48-51 . Chrysomya albiceps – anterior thoracic spiracle brown (Fig. 11), male genitalia on figs 56-59 . Chrysomya megacephala 6. – upper and lower calypters bright (Fig. 13), basicosta yellow (Fig. 21) . Phormia regina – upper and lower calypters dark brown (Fig.