Mahabharata and Bhagavad Gita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

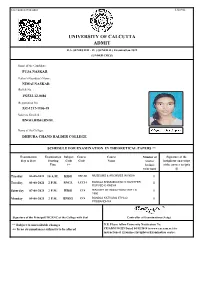

University of Calcutta Admit

532/1800865758/0401 5320942 UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA ADMIT B.A. SEMESTER - IV ( GENERAL) Examination-2021 (UNDER CBCS) Name of the Candidate : PUJA NASKAR Father's/Guardian's Name : NIMAI NASKAR Roll & No. : 192532-12-0486 Registration No. 532-1212-1106-19 Subjects Enrolled : BNGG,HISG,BNGL Name of the College : DHRUBA CHAND HALDER COLLEGE SCHEDULE FOR EXAMINATION IN THEORETICAL PAPERS ** Examination Examination Subject Course Course Number of Signature of the Day & Date Starting Code Code Name Answer invigilator on receipt Time ++ book(s) of the answer script/s to be used @ Tuesday 03-08-2021 10 A.M. HISG SEC-B1 MUSEUMS & ARCHIVES IN INDIA 1 Tuesday 03-08-2021 2 P.M. BNGL LCC2-1 BANGLA BHASABIGYAN O SAHITYER 1 RUPVED O KABYA Saturday 07-08-2021 2 P.M. HISG CC4 HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1 1950 Monday 09-08-2021 2 P.M. BNGG CC4 BANGLA KATHASAHITYA O 1 PROBANDHYA Signature of the Principal/TIC/OIC of the College with Seal Controller of Examinations (Actg.) ** Subject to unavoidable changes N.B. Please follow University Notification No. ++ In no circumstances subject/s to be altered CE/ADM/18/229 Dated 04/12/2018 in www.cuexam.net for instruction of Examinee/Invigilator/Examination centre. 532/1800908303/0402 5320963 UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA ADMIT B.A. SEMESTER - IV ( GENERAL) Examination-2021 (UNDER CBCS) Name of the Candidate : JABA MONDAL Father's/Guardian's Name : SUBARNA MONDAL Roll & No. : 192532-12-0487 Registration No. 532-1212-1126-19 Subjects Enrolled : HISG,SOCG,BNGL Name of the College : DHRUBA CHAND HALDER COLLEGE SCHEDULE FOR EXAMINATION IN THEORETICAL PAPERS ** Examination Examination Subject Course Course Number of Signature of the Day & Date Starting Code Code Name Answer invigilator on receipt Time ++ book(s) of the answer script/s to be used @ Tuesday 03-08-2021 10 A.M. -

Shankar Ias Academy Test 18 - Geography - Full Test - Answer Key

SHANKAR IAS ACADEMY TEST 18 - GEOGRAPHY - FULL TEST - ANSWER KEY 1. Ans (a) Explanation: Soil found in Tropical deciduous forest rich in nutrients. 2. Ans (b) Explanation: Sea breeze is caused due to the heating of land and it occurs in the day time 3. Ans (c) Explanation: • Days are hot, and during the hot season, noon temperatures of over 100°F. are quite frequent. When night falls the clear sky which promotes intense heating during the day also causes rapid radiation in the night. Temperatures drop to well below 50°F. and night frosts are not uncommon at this time of the year. This extreme diurnal range of temperature is another characteristic feature of the Sudan type of climate. • The savanna, particularly in Africa, is the home of wild animals. It is known as the ‘big game country. • The leaf and grass-eating animals include the zebra, antelope, giraffe, deer, gazelle, elephant and okapi. • Many are well camouflaged species and their presence amongst the tall greenish-brown grass cannot be easily detected. The giraffe with such a long neck can locate its enemies a great distance away, while the elephant is so huge and strong that few animals will venture to come near it. It is well equipped will tusks and trunk for defence. • The carnivorous animals like the lion, tiger, leopard, hyaena, panther, jaguar, jackal, lynx and puma have powerful jaws and teeth for attacking other animals. 4. Ans (b) Explanation: Rivers of Tamilnadu • The Thamirabarani River (Porunai) is a perennial river that originates from the famous Agastyarkoodam peak of Pothigai hills of the Western Ghats, above Papanasam in the Ambasamudram taluk. -

![Personality Development - English 1 Personality Development - English 2 Initiative for Moral and Cultural Training [IMCTF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8831/personality-development-english-1-personality-development-english-2-initiative-for-moral-and-cultural-training-imctf-168831.webp)

Personality Development - English 1 Personality Development - English 2 Initiative for Moral and Cultural Training [IMCTF]

Personality Development - English 1 Personality Development - English 2 Initiative for Moral and Cultural Training [IMCTF] Personality Development (English) Details Book Name : Personality Development (English) Edition : 2015 Pages : 224 Size : Demmy 1/8 Published by : Initiative for Moral and Cultural Training Foundation (IMCTF) Head Office : 4th Floor, Ganesh Towers, 152, Luz Church Road, Mylapore, Chennai - 600 004. Admin Office : 2nd Floor, “Gargi”, New No.6, (Old No.20) Balaiah Avenue, Luz, Mylapore, Chennai - 600 004. Email : [email protected], Website : www.imct.org.in This book is available on Website : www.imct.org.in Printed by : Enthrall Communications Pvt. Ltd., Chennai - 30 © Copy Rights to IMCTF Personality Development - English Index Class 1 1. Oratorical ................................................................................................12 2. Great sayings by Thiruvalluvar .........................................................12 3. Stories .......................................................................................................12 4. Skit ........................................................................................................15 Class 2 1. Oratorical .................................................................................................16 2. Poems .......................................................................................................16 3. Stories .......................................................................................................18 4. -

Indian Hieroglyphs

Indian hieroglyphs Indus script corpora, archaeo-metallurgy and Meluhha (Mleccha) Jules Bloch’s work on formation of the Marathi language (Bloch, Jules. 2008, Formation of the Marathi Language. (Reprint, Translation from French), New Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN: 978-8120823228) has to be expanded further to provide for a study of evolution and formation of Indian languages in the Indian language union (sprachbund). The paper analyses the stages in the evolution of early writing systems which began with the evolution of counting in the ancient Near East. Providing an example from the Indian Hieroglyphs used in Indus Script as a writing system, a stage anterior to the stage of syllabic representation of sounds of a language, is identified. Unique geometric shapes required for tokens to categorize objects became too large to handle to abstract hundreds of categories of goods and metallurgical processes during the production of bronze-age goods. In such a situation, it became necessary to use glyphs which could distinctly identify, orthographically, specific descriptions of or cataloging of ores, alloys, and metallurgical processes. About 3500 BCE, Indus script as a writing system was developed to use hieroglyphs to represent the ‘spoken words’ identifying each of the goods and processes. A rebus method of representing similar sounding words of the lingua franca of the artisans was used in Indus script. This method is recognized and consistently applied for the lingua franca of the Indian sprachbund. That the ancient languages of India, constituted a sprachbund (or language union) is now recognized by many linguists. The sprachbund area is proximate to the area where most of the Indus script inscriptions were discovered, as documented in the corpora. -

Download This PDF File

ISSN 1712-8056[Print] Canadian Social Science ISSN 1923-6697[Online] Vol. 8, No. 2, 2012, pp. 132-139 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.css.1923669720120802.1985 www.cscanada.org Iranian People and the Origin of the Turkish-speaking Population of the North- western of Iran LE PEUPLE IRANIEN ET L’ORIGINE DE LA POPULATION TURCOPHONE AU NORD- OUEST DE L’IRAN Vahid Rashidvash1,* 1 Department of Iranian Studies, Yerevan State University, Yerevan, exception, car il peut être appelé une communauté multi- Armenia. national ou multi-raciale. Le nom de Azerbaïdjan a été *Corresponding author. l’un des plus grands noms géographiques de l’Iran depuis Received 11 December 2011; accepted 5 April 2012. 2000 ans. Azar est le même que “Ashur”, qui signifi e feu. En Pahlavi inscriptions, Azerbaïdjan a été mentionnée Abstract comme «Oturpatekan’, alors qu’il a été mentionné The world is a place containing various racial and lingual Azarbayegan et Azarpadegan dans les écrits persans. Dans groups. So that as far as this issue is concerned there cet article, la tentative est faite pour étudier la course et is no difference between developed and developing les gens qui y vivent dans la perspective de l’anthropologie countries. Iran is not an exception, because it can be et l’ethnologie. En fait, il est basé sur cette question called a multi-national or multi-racial community. que si oui ou non, les gens ont résidé dans Atropatgan The name of Azarbaijan has been one of the most une race aryenne comme les autres Iraniens? Selon les renowned geographical names of Iran since 2000 years critères anthropologiques et ethniques de personnes dans ago. -

Ramayana of * - Valmeeki RENDERED INTO ENGLISH with EXHAUSTIVE NOTES BY

THE Ramayana OF * - Valmeeki RENDERED INTO ENGLISH WITH EXHAUSTIVE NOTES BY (. ^ ^reenivasa jHv$oiu$ar, B. A., LECTURER S. P G. COLLEGE, TRICHINGj, Balakanda and N MADRAS: * M. K. PEES8, A. L. T. PRKS8 AND GUARDIAN PBE8S. > 1910. % i*t - , JJf Reserved Copyright ftpfiglwtd. 3 [ JB^/to PREFACE The Ramayana of Valmeeki is a most unique work. The Aryans are the oldest race on earth and the most * advanced and the is their first ; Ramayana and grandest epic. The Eddas of Scandinavia, the Niebelungen Lied of Germany, the Iliad of Homer, the Enead of Virgil, the Inferno, the Purgatorio, and the Paradiso of Dante, the Paradise Lost of Milton, the Lusiad of Camcens, the Shah Nama of Firdausi are and no more the Epics ; Ramayana of Valmeeki is an Epic and much more. If any work can clam} to be the Bible of the Hindus, it is the Ramayana of Valmeeki. Professor MacDonell, the latest writer on Samskritha Literature, says : " The Epic contains the following verse foretelling its everlasting fame * As long as moynfain ranges stand And rivers flow upon the earth, So long will this Ramayana Survive upon the lips of men. This prophecy has been perhaps even more abundantly fulfilled than the well-known prediction of Horace. No pro- duct of Sanskrit Literature has enjoyed a greater popularity in India down to the present day than the Ramayana. Its story furnishes the subject of many other Sanskrit poems as well as plays and still delights, from the lips* of reciters, the hearts of the myriads of the Indian people, as at the 11 PREFACE great annual Rama-festival held at Benares. -

Ravana Sends Shardula to Spy

“Om Sri Lakshmi Narashimhan Nahama” Valmiki Ramayana – Yuddha Kanda – Chapter 29 Ravana Sends Shardula to Spy Summary Ravana reprimands Shuka and Sarana, asking them to leave the assembly. He again sends some spies to the place of Rama and Lakshmana. Those spies were got caught by Vibhishana and the monkeys start harassing them. But the compassionate Rama gets them released and the spies reach back Lanka. Chapter [Sarga] 29 in Detail shukena tu samaakhyaataams taan dristvaa hari yuuthapaan | laksmanam ca mahaaviiryam bhujam raamasya daksinam || 2-29-1 samiipastham ca raamasya bhraataram svam vibhiisanam | sarva vaanara raajam ca sugriivam bhiima vikramam || 2-29-2 angadam caapi balinam vajrahastaatmajaatmajam | hanuumantam ca vikraantam jaambavantam ca durjayam || 2-29-3 susenam kumudam niilam nalam ca plavagarsabham | gajam gavaaksham sharabham vaindam ca dvividam tathaa || 2-29-4 kimcid aavigna hridayo jaata krodhah ca raavanah | bhartsayaam aasa tau viirau kathaa ante shuka saaranau || 2-29-5 Beholding those foremost of monkey leaders pointed out by Shuka- the most valiant Lakshmana; Rama’s right arm, his own brother Vibhishana standing close to Rama, the terribly powerful Sugreeva the king of all monkeys, the strong Angada grandson of Indra the wielder of thunderbolt, the powerful Hanuman, the invincible Jambavan, Sushena, Kumuda, Nila, Nala the excellent of monkeys, Gaja, Gavaaksha, Sharabha, Mainda and Dvivida- that Ravana – his heart became agitated a little, was enraged and then abused those two heroes Shuka and Sarana who had completed their report. Page 1 of 7 “Om Sri Lakshmi Narashimhan Nahama” Valmiki Ramayana – Yuddha Kanda – Chapter 29 adho mukhau tau pranataav abraviit shuka saaranau | rosa gadgadayaa vaacaa samrabdhah parusam vacah || 2-29-6 Ravana spoke (the following) excited and harsh words, in a voice choked in anger to Shuka and Sarana who stood saluting with their faces bent down. -

Né Pour Briller, Né Pour Réussir Avec Une Maîtrise Parfaite, Le Pr. Lal

Né pour briller, né pour réussir Avec une maîtrise parfaite, le Pr. Lal insère des explications dans le texte même, s’épargnant ainsi les notes. Critique, par Pradip Bhattacharya. Le Mahabharata de Vyasa. Le Karna Parva (livre de Karna), transcréé du sanskrit par le Pr Lal, Writers Workshop, Rps 1000 (broché). Tirage spécial en 50 exemplaires numérotés, avec un frontiscipe original peint à la main, Rps 2000. La bataille du Kurukshetra présente un double point fort : le duel Karna-Arjuna et la confrontation finale Bhima-Duryodhana. Nous arrivons au troisième livre de la bataille, l’ancienne génération est tombée ; et en même temps qu’elle, ses obsessions. La soif de revanche de Drupada sur Bhishma et Drona a été assouvie par deux de ses fils, engendrés dans ce but. Avant d’être décapité, Drona tue deux des principaux alliés des Pandava : Drupada et Virata. L’ancien Bahlika, Bhagadatta, Bhurishrava – tous sont tués. Rien ne fait plus obstacle au désir de Duryodhana de nommer Karna commandant en chef, un désir auquel il avait dû renoncer par deux fois. Bien que Karna ait fui au moins par trois fois du champ de bataille durant le commandement de Drona, Duryodhana s’accroche à son invincibilité avec une foi aveugle, avec le désespoir d’un homme qui se noie. Le lecteur notera un trait unique du style du Pr. Lal dans sa transcréation : l’utilisation de doublets chaque fois que Vyasa n’emploie pas le nom usuel d’un personnage. Ainsi, avec une maîtrise parfaite, il insère des explications dans le texte même, s’épargnant les notes. -

The Concept of Mother Goddess in the Art and Literature of Orissa Jayanti Rath

Orissa Review September - 2009 The Concept of Mother Goddess in the Art and Literature of Orissa Jayanti Rath The concept of Mother Goddess probably accommodates the largest number of paradoxes. She is a virgin and yet she is also the mother, a mother goddess. She is the Saivite Parvati and also a Vaishnavi. She is the purest of the pure. She is blood-thirsty Kali and also the very embodiment of the merciful and beautiful Amba or Lalita. She is invincible; she is the slayer of demons. She is Durga, with many arms. She is Sakti, the divine principle. This multiplicity of paradoxes proves the continuous popularity of the Sakti cult in India over the centuries. The very word Sakti denotes power. She can be seen through the different phenomenan of life. Durga Saptasati says that everyone has inherent power called Sakti, which is a manifestation of Para Sakti, the supreme goddess. In the Sakta scheme of cosmogonical evolution, the unmanifested prakarti alone existed before creation. She wished to create, and having assumed the form of the great mother, created Brahma, Vishnu and Siva. Referring to the Mother Goddess cult of Mohenjodaro, Marshall rightly observed that it was in the later Sakta phase of Saktism gained prominence in the epic the primitive Mother Goddess cult that the Devi became the manifestation of the all-powerful period when gods receded into the background. female principle, viz. the Prakriti or Sakti having In the Mahabharata Aditi is regarded as mother associated with the male principle, the Purusa. of the Adityas. She is also the mother of Vasus She becomes Jagadamba or Jagatmata, the and Rudras. -

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 5, Issue 4 April 2011

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 5, Issue 4 April 2011 HARI OM March 1st, Swamiji returned from India where he visited holy places and sister branch in Bangalore. And a fruitful trip to Maha Sarovar (West Kolkata) water to celebrate Mahashivatri here in our temple Sunnyvale. Shiva Abhishekham was performed every 3 hrs with milk, yogurt, sugar, juice and other Dravyas. The temple echoed with devotional chanting of Shiva Panchakshari Mantram, Om Namah Shivayah. During day long Pravachan Swamiji narrated 2 special stories. The first one was about Ganga, and why we pour water on top of Shiva Linga and the second one about Bhasmasura. King Sagar performed powerful Ashwamedha Yagna (Horse sacrifice) to prove his supremacy. Lord Indra, leader of the Demi Gods, fearful of the results of the yagna, stole the horse. He left the horse at the ashram of Kapila who was in deep meditation. King Sagar's 60,000 sons (born to Queen Sumati) and one son Asamanja (born to queen Keshini) were sent to search the horse. When they found the horse at Shri N. Swamiji performing Aarthi KapilaDeva's Ashram, they concluded he had stolen it and prepared to attack him. The noise disturbed the meditating Rishi/Sage VISAYA VINIVARTANTE NIRAHARASYA DEHINAH| KapilaDeva and he opened his eyes and cursed the sons of king sagara for their disrespect to such a great personality. Fire emanced RASAVARJAM RASO PY ASYA from their own bodies and they were burned to ashes instantly. Later PARAM DRSTVA NIVARTATE || king Sagar sent his Grandson Anshuman to retreive the horse.