Woodham Walter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits Made Under S31(6) Highways Act 1980

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits made under s31(6) Highways Act 1980 and s15A(1) Commons Act 2006 For all enquiries about the contents of the Register please contact the: Public Rights of Way and Highway Records Manager email address: [email protected] Telephone No. 0345 603 7631 Highway Highway Commons Declaration Link to Unique Ref OS GRID Statement Statement Deeds Reg No. DISTRICT PARISH LAND DESCRIPTION POST CODES DEPOSITOR/LANDOWNER DEPOSIT DATE Expiry Date SUBMITTED REMARKS No. REFERENCES Deposit Date Deposit Date DEPOSIT (PART B) (PART D) (PART C) >Land to the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops Christopher James Harold Philpot of Stortford TL566209, C/PW To be CM22 6QA, CM22 Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton CA16 Form & 1252 Uttlesford Takeley >Land on the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops TL564205, 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. 6TG, CM22 6ST Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM1 4LN Plan Stortford TL567205 on behalf of Takeley Farming LLP >Land on east side of Station Road, Takeley, Bishops Stortford >Land at Newland Fann, Roxwell, Chelmsford >Boyton Hall Fa1m, Roxwell, CM1 4LN >Mashbury Church, Mashbury TL647127, >Part ofChignal Hall and Brittons Farm, Chignal St James, TL642122, Chelmsford TL640115, >Part of Boyton Hall Faim and Newland Hall Fann, Roxwell TL638110, >Leys House, Boyton Cross, Roxwell, Chelmsford, CM I 4LP TL633100, Christopher James Harold Philpot of >4 Hill Farm Cottages, Bishops Stortford Road, Roxwell, CMI 4LJ TL626098, Roxwell, Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton C/PW To be >10 to 12 (inclusive) Boyton Hall Lane, Roxwell, CM1 4LW TL647107, CM1 4LN, CM1 4LP, CA16 Form & 1251 Chelmsford Mashbury, Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM14 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. -

Initial Document Template

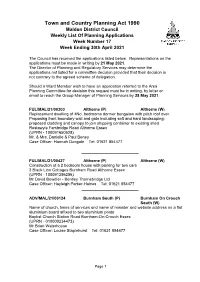

Town and Country Planning Act 1990 Maldon District Council Weekly List Of Planning Applications Week Number 17 Week Ending 30th April 2021 The Council has received the applications listed below. Representations on the applications must be made in writing by 21 May 2021. The Director of Planning and Regulatory Services may determine the applications not listed for a committee decision provided that their decision is not contrary to the agreed scheme of delegation. Should a Ward Member wish to have an application referred to the Area Planning Committee for decision this request must be in writing, by letter or email to reach the Group Manager of Planning Services by 28 May 2021. FUL/MAL/21/00300 Althorne (P) Althorne (W) Replacement dwelling of 4No. bedrooms dormer bungalow with pitch roof over. Proposing front boundary wall and gate including soft and hard landscaping; proposed cladding and canopy to join shipping container to existing shed Restawyle Fambridge Road Althorne Essex (UPRN - 100091650528) Mr. & Mrs. Danielle & Paul Beney Case Officer: Hannah Dungate Tel: 01621 854477 FUL/MAL/21/00427 Althorne (P) Althorne (W) Construction of a 2 bedroom house with parking for two cars 3 Black Lion Cottages Burnham Road Althorne Essex (UPRN - 100091256256) Mr David Bowdler - Bentley Thornebridge Ltd Case Officer: Hayleigh Parker-Haines Tel: 01621 854477 ADV/MAL/21/00124 Burnham South (P) Burnham On Crouch South (W) Name of church, times of services and name of minister and website address on a flat aluminium board affixed to two aluminium posts Baptist Church Station Road Burnham-On-Crouch Essex (UPRN - 010000234473) Mr Brian Waterhouse Case Officer: Louise Staplehurst Tel: 01621 854477 Page 1 HOUSE/MAL/21/00328 Burnham South (P) Burnham On Crouch South (W) Demolition of the existing garage and porch and proposed two storey side and single storey rear extensions, alterations to fenestration and new access gates. -

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List Produced Under Section 36 of the Highways Act

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: MALDON Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: ALTHORNE ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS AUSTRAL WAY UNCLASSIFIED BARNES FARM DRIVE PRIVATE ROAD BRIDGEMARSH LANE PRIVATE ROAD BURNHAM ROAD B ROAD CHESTNUT FARM DRIVE PRIVATE ROAD CHESTNUT HILL PRIVATE ROAD DAIRY FARM ROAD UNCLASSIFIED FAMBRIDGE ROAD B ROAD GARDEN CLOSE UNCLASSIFIED GREEN LANE CLASS III HIGHFIELD RISE UNCLASSIFIED LOWER CHASE PRIVATE ROAD MAIN ROAD B ROAD OAKWOOD COURT UNCLASSIFIED RIVER HILL PRIVATE ROAD SOUTHMINSTER ROAD B ROAD STATION ROAD PRIVATE ROAD SUMMERDALE UNCLASSIFIED SUMMERHILL CLASS III SUNNINGDALE ROAD PRIVATE ROAD THE ENDWAY CLASS III UPPER CHASE PRIVATE ROAD WOODLANDS UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 23 Highways and Transportation Department Page 2 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: MALDON Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: ASHELDHAM ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS BROOK LANE PRIVATE ROAD GREEN LANE CLASS III HALL ROAD UNCLASSIFIED RUSHES LANE PRIVATE ROAD SOUTHMINSTER ROAD B ROAD SOUTHMINSTER ROAD UNCLASSIFIED TILLINGHAM ROAD B ROAD TOTAL 7 Highways and Transportation Department Page 3 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: MALDON Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: BRADWELL-ON-SEA ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS BACONS CHASE PRIVATE ROAD BACONS CHASE UNCLASSIFIED BATE DUDLEY DRIVE UNCLASSIFIED BRADWELL AIRFIELD PRIVATE ROAD BRADWELL ROAD B ROAD BRADWELL ROAD CLASS III BUCKERIDGE -

Parish Community Agent Email Address Phone Number Althorne Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Asheldham Kelly

Parish Community Agent Email Address Phone number Althorne Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Asheldham Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Bradwell-on-Sea Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Burnham-on-Crouch Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Cold Norton Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Dengie Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Goldhanger Eileen Smith [email protected] 07540720612 Great Braxted Eileen Smith [email protected] 07540720612 Great Totham Eileen Smith [email protected] 07540720612 Hazeleigh Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Heybridge Eileen Smith [email protected] 07540720612 Langford Eileen Smith [email protected] 07540720612 Latchingdon Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Little Braxted Eileen Smith [email protected] 07540720612 Little Totham Eileen Smith [email protected] 07540720612 Maldon Eileen Smith [email protected] 07540720612 Mayland Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Mundon Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 North Fambridge Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Purleigh Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 St. Lawrence Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Southminster Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Steeple Kelly Coombs [email protected] 07540720610 Stow Maries Kelly Coombs [email protected] -

The Forty Plus Cycling Club Year 1989

The Forty Plus Cycling Club Year 1989 I FORTY PLUS CYCLING iCLUB. ; . I .. ! " ? • • ^ i i ^ '•• 'ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AT ThE jdKN MARSHALL PULL, ^CHRISTCHURCH INDUSTRIAL CENTRE, 27 BLACKFRIARS RE., iLONDONt S.E.I.. ON 28TH JANUARY 1989 AT 11.00 A.M. i AGENDA 1. Election of Chairnsan for the Meeting 2, ! ;Minuties of A.G.M. 30th January 1988, as published with "Signpost", ! Decenber 1988 3".! Matters Arising froE Minutes - i k. \ General Secretary's Report 5. Treasurer's Report (Statecient of Accounts overleaf) 6. Meabership Secretary's Report 7. •Proposed by the Committee To consider the granting of;- honorary oeabership to peKbbrs reaching 90 years of age 8. Proposed by the ConDittee:- That nieuibers' annual subscriptions . be raised to £2,50 for individuals! and to £3.00 for narried couples, : with computed subscriptions i aidjusted "pro rata I" 9. Proposed by Mrs. E. Paine Rule ^(B) - CoEiiPittee Meetings Seconded " W.O. Paine" That the words "in London" be deleted 10. Proposed by Mrs. E. Paine Rule 5(A) ~ Subscriptions . Seconded " Wi.0. Paine ThatthQ existing wording be repl^jced by the following "The:appropriate annual subscrip• tion shall be payable on 1st j January each year; this payiaeht to cover cecabership until 31st DeceDber of that year". 11 iElection of Officers for 1989 ;1. President 7. "Signpost" Editor 2. Chairaan 8. " Printer 3. General Sec. 9. " Distributor ,k, treasurer 10, " Address Typist 5. Membership Sec. 11; Runs List Typist :6. Auditor 12. Section Secretaries - Sussex South Beds St. Albans , I East Herts. • Stevenage v : Eastern/Northern 'A' ; Eastern/Northern 'B' . -

North Fambridge Church Road, North Fambridge, Essex CM3 6LU

Mayfields - North Fambridge Church Road, North Fambridge, Essex CM3 6LU MMayfields_A4_16pp.inddayfields_A4_16pp.indd 1 227/02/20177/02/2017 15:1715:17 MMayfields_A4_16pp.inddayfields_A4_16pp.indd 2 227/02/20177/02/2017 15:1715:17 welcome to Mayfields North Fambridge Ideally located on Church Road in the heart of the pretty Essex village of North Fambridge, Mayfields offers a mix of eight 2 and 3 bedroom bungalows and 4 bedroom houses. Traditionally built with an excellent specification. The village has a railway station just half a mile from the development which offers direct peak time trains to London Liverpool Street. The A130 is nearby, offering easy access to both the A12 and the A127. At the end of the road is North Fambridge Yacht Club and Marina with great walks and a friendly cafe. The village is also home to The Ferry Boat Inn, a 500 year old riverside pub. For a friendly and relaxed lifestyle Mayfields is perfect. www.moodyhomes.co.uk MMayfields_A4_16pp.inddayfields_A4_16pp.indd 3 227/02/20177/02/2017 15:1715:17 mayfields in no rth fambridge “the ideal quiet village LI fe and just a stone s throw from the river Crouch” A502 Silver End A131 Layer M11 Marney Witham A414 Mersea A414 Island A130 A12 A10 Chelmsford Little 7 Baddow Maldon M11 A414 A414 A1114 Tillingham A12 24 M25 25 27 Maylandsea 26 6 North Fambridge A12 5 A130 A10 M25 M11 Billericay Burnham-on-Crouch A406 28 Brentwood Wickford Rayleigh A12 A127 29 London Basildon Southend A406 A127 Airport A12 M25 A13 Southend London Leigh-on-Sea Liverpool St. -

The Woodham Walter Village Design Statement

APPENDIX 1 Woodham Walter Parish Council The Woodham Walter Village Design Statement 2016 APPENDIX 1 Village Design Statement 2016 Woodham Walter Parish Council Contents and Foreword Foreword Contents Following the introduction of neighbourhood planning by Central Government, in the spring of 2013, Foreword the Woodham Walter Parish Council set up a Working Party to prepare a Village Design Statement Page document as part of the community led planning initiative. 1 Introduction 1 During 2014 every household in the Parish was circulated with a Questionnaire designed to gauge 2 Evolution public views on how they wished to see their village environment developing in the future. The Geology, Topography and Boundaries 2 response to this Questionnaire was outstanding, in excess of 75% returns and the results were Settlement Growth 3 Landscape Characteristics 4 published at Bell Meadow Day 2014 as well as being incorporated on the Parish Council Website. Areas of Defined Settlement 5 Those results have now been collated into this document, the first draft of which was exhibited at the Area Settlement Characteristics and Views 6 Building Styles 18 2015 Annual Parish Meeting and has now been submitted to the Maldon District Council for approval Heritage Assets 21 as a supplementary document to the Maldon District Characterisation Document that in turn will Conservation Area 23 relate to the Council Local Development Plan and therefore is pertinent to the planning process. Threats to Character 24 This Village Design Statement is Woodham Walter specific and gives a detailed description of the 3 The Built Environment existing character and main features of design in the village and guidelines for how this should be Background 25 respected in any new development. -

Area Served by South Woodham Mobile Library (SWM) 2016/17

Area served by South Woodham mobile library (SWM) 2016/17 Week 1 Tuesday visits Fortnightly Week 1 Dates Location Stop Name Arrives Leaves Ramsden Bellhouse Bellhouse Pre School 9.30 10.00 Ramsden Heath Ramsden Heath Pre School 10.05 10.35 Nov – 8, 22 Downham Downham Road 10.45 11.10 Dec – 6 Jan – 3, 17, 31 Runwell The Greenway 11.30 11.50 Feb – 14, 28 Ramsden Heath Allens Road 13.45 14.15 Mar – 14, 28 Ramsden Heath Short Lane 14.20 16.00 Ramsden Bellhouse Village Hall 16.10 16.30 Wednesday visits Fortnightly Week 1 Dates Location Stop Name Arrives Leaves Mayland Whitefield Court 9.30 9.50 Mayland Little Nipperz Playgroup 9.55 10.15 Maylandsea George Cardnell Way 10.20 10.40 Maylandsea Lawling Playing Field 10.45 11.15 Nov – 9, 23 Purleigh Snows Corner 11.40 12.00 Dec – 7 Purleigh The Bell 12.05 12.20 Jan – 4, 18 Stow Maries Church Hall 12.30 12.45 Feb – 1, 15 Mar – 1, 15, 29 Cold Norton Village Hall 13.50 14.20 East Hanningfield Old Church Road 14.35 14.55 East Hanningfield Village Hall Car Park 15.15 16.00 Rettendon Salforal Close 16.05 16.25 Rettendon Meadow Road 16.30 16.45 South Woodham Mobile (SWM Wk 1) continued Thursday visits Fortnightly Week 1 Dates Location Stop Name Arrives Leaves Ulting Does Corner 9.40 9.55 Ulting Ulting Lane / Water Co. Houses 10.00 10.15 Nov – 10, 24 Heybridge Colne House 10.45 11.15 Dec – 8 Heybridge Coopers Avenue 11.20 11.50 Jan – 5, 19 Heybridge Basin Bus Stop 12.00 12.15 Feb – 2, 16 Heybridge Daisy Meadows Car Park 12.20 12.50 Mar – 2, 16, 30 Goldhanger Village Hall 14.00 14.30 Heybridge Plantation -

Wepray Aug - Sept 2019

WEPRAY AUG - SEPT 2019 Praying for each other in Essex & East London #chelmsdioprayers Chelmsford Diocese Prayer Diary August “Before they call I will answer; while they are still speaking I will hear” Isaiah 65:24 Thu 1 Southminster (St Leonard) and Steeple (St Lawrence and All Saints) Clergy: Peter Begley (PIC). Southminster Primary School: Pauline Ward (Executive HT), Chris Beazeley (Interim Head of School). The Missionary District of Oeste-Brasil, the Diocese of Boga (Congo) and the Diocese of Port Elizabeth (Southern Africa) Fri 2 Woodham Mortimer (St Margaret) w Hazeleigh and Woodham Walter (St Michael) Clergy: Vacancy (PIC), Julie Willmot (A). Woodham Walter School: Sue Dodd (HT). Mayland (St Barnabas) and Latchingdon (Christ Church) Clergy: Vacancy (R). The Dioceses of Offa (Nigeria), Bolivia (South America) and Karimnagar (South India) Sat 3 One of today’s readings – Leviticus 25.1, 8-17 – tells us about the year of Jubilee, the fiftieth year. In the Old Testament Jubilee is a radical concept – that every fiftieth year there will be a redistribution of property and wealth. This rooted in the conviction that everything is a gift from God anyway and that gifts are for sharing. There is a real challenge for us, not just about property and money but about the whole way we understand the gifts God gives us. It is too easy to think that these are our possessions which we need to protect when of course they are always gifts for sharing. The Dioceses of Karnataka Central, Karnataka North and Karnataka South (South India) Please refer to the Notes and Abbreviations on the back cover. -

82322 Essex CC X85.Indd

Essex County Council (Footpath 4, Burnham-on-Crouch) (Temporary Prohibition of Use) Order 2018 Notice is hereby given that the above Order made by Essex County Council, under s14 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, has been continued in force with the consent of the Secretary of State for the Department for Transport until 3 January 2020. Effect of the order: To temporarily close that length of Footpath 4, Burnham-on-Crouch in the District of Maldon, from its junction with Creeksea Lane south east for a distance of approximately 370 metres. The alternative route will be via Creeksea Lane, B1010 Maldon Road, Springfield Road, Footpath 4 and vice versa. The closure commenced on 3 July 2018 and is required for the safety of the public while the upgrading of Footpath 4 is undertaken. (Footpath 3 & 5, Cold Norton and Footpath 11 & 13, Purleigh) (Temporary Prohibition of Use) Order 2019 Notice is hereby given that the Essex County Council has made the above Order under Section 14(1) of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984. Effect of the order: To temporarily close the following length of Footpath 3 & 5, Cold Norton and Footpath 11 & 13, Purleigh in the District of Maldon: Road Description Footpath 3, From the junction with Flambirds Chase and Cold Norton/ Footpath 3, Cold Norton, east to the junction with Footpath 13, Hackmans Lane and Footpath 13, Purleigh. Purleigh Footpath 11, From the junction with Flambirds Chase and Purleigh/ Footpath 11, Purleigh, south for a distance of Footpath 5, approximately 1620 metres to the junction with Cold Norton Footpath 5, Cold Norton and Footpath 4, Stow Maries. -

Parish Profile for the Parishes of St Margaret, Woodham Mortimer with Hazeleigh and St Michael the Archangel, Woodham Walter

Parish Profile for the Parishes of St Margaret, Woodham Mortimer with Hazeleigh and St Michael the Archangel, Woodham Walter St Margaret’s has the following Parish Church prayer: Loving Lord God, enable this church to do your will Make us vulnerable that we may speak with calm humility Make us outward looking, that we may care deeply Make us a community of peacemakers and bridge builders In the midst of turbulence let the church make space For the hearing of your still small voice Amen 1. Summary of the Churches and District: The benefice comprises the rural villages of Woodham Mortimer with Hazeleigh and Woodham Walter, near Maldon in Essex. Both St Margaret’s and St Michael’s churches follow varied “middle of the road” traditions, and are working towards being part of the Diocesan Vision “Transforming Presence”. The congregation of St Margaret’s is on average 25 and St Michael’s has an average congregation of 24. We are looking for a priest to work on a House for Duty basis which we have found works well. We would like the new priest to have a visible presence within the parishes, particularly in association with the Church School in Woodham Walter. 2. Gifts/Skills/Experience: Ideally the new priest will have the skills to merge the traditional values of the church with modern approaches, while taking into account the age profile of our congregation. The new priest should have the ability to lead and teach our current members, and work to attract new and younger members of the non church-going community into our congregation. -

Eb056b Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment Site

EB056b Maldon District Council Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment Volume 2: Final Site Schedules May 2012 EB056b Maldon SHLAA Volume 2 – Site Schedules Introduction Site area (ha): This is the gross site area measured in hectares. If a site has been found suitable and available, it becomes an In many cases, the ‘developable area’ of a site has been used ‘accepted’ SHLAA site. It is then tested for ‘achievability’. as the basis of the site assessment, which is smaller than This report represents Volume 2 of the Maldon District Council the gross site area. This is because some of the site is not If a site is shown as unsuitable or unavailable, it is discounted. Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) considered to be suitable for housing because of, e.g. flood risk, Update 2012. topography or an environmental designation such as a Nature Achievable (H/M/L): This is the viability assessment of the Reserve. site. A site is considered viable if it makes economic sense to It has been undertaken by URS planning consultants on behalf develop the site. The results of a viability modelling exercise of Maldon District Council. Current and surrounding use: This describes the current use of indicate whether a site has high, medium or low viability. If a the site and its surrounding use, if relevant. site is assessed as High, it is above the viability threshold set The Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) in the model; if it is Medium, it is below the viable threshold is a technical assessment of sites which could potentially Within Development Boundary (Y/N/Adjoining).