Strategic Individuals and Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recorder 298.Pages

RECORDER RecorderOfficial newsletter of the Melbourne Labour History Society (ISSN 0155-8722) Issue No. 298—July 2020 • From Sicily to St Lucia (Review), Ken Mansell, pp. 9-10 IN THIS EDITION: • Oil under Troubled Water (Review), by Michael Leach, pp. 10-11 • Extreme and Dangerous (Review), by Phillip Deery, p. 1 • The Yalta Conference (Review), by Laurence W Maher, pp. 11-12 • The Fatal Lure of Politics (Review), Verity Burgmann, p. 2 • The Boys Who Said NO!, p. 12 • Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin (Review), by Nick Dyrenfurth, pp. 3-4 • NIBS Online, p. 12 • Dorothy Day in Australia, p. 4 • Union Education History Project, by Max Ogden, p. 12 • Tribute to Jack Mundey, by Verity Burgmann, pp. 5-6 • Graham Berry, Democratic Adventurer, p. 12 • Vale Jack Mundey, by Brian Smiddy, p. 7 • Tribune Photographs Online, p. 12 • Batman By-Election, 1962, by Carolyn Allan Smart & Lyle Allan, pp. 7-8 • Melbourne Branch Contacts, p. 12 • Without Bosses (Review), by Brendan McGloin, p. 8 Extreme and Dangerous: The Curious Case of Dr Ian Macdonald Phillip Deery His case parallels that of another medical doctor, Paul Reuben James, who was dismissed by the Department of Although there are numerous memoirs of British and Repatriation in 1950 for opposing the Communist Party American communists written by their children, Dissolution Bill. James was attached to the Reserve Australian communists have attracted far fewer Officers of Command and, to the consternation of ASIO, accounts. We have Ric Throssell’s Wild Weeds and would most certainly have been mobilised for active Wildflowers: The Life and Letters of Katherine Susannah military service were World War III to eventuate, as Pritchard, Roger Milliss’ Serpent’s Tooth, Mark Aarons’ many believed. -

Z432 Waterside Workers' Federation of Australia, Federal Office Deposit

Z432 Waterside Workers’ Federation of Australia, Federal Office deposit 6 Download list Amended July 2008 _______________________________________________________________ ANU ARCHIVES PROGRAM Telephone: +61 2 6125 2219 Noel Butlin Archives Centre Facsimile: +61 2 6125 0140 Email: [email protected] Incorporating the ANU Archives of Business & Labour Web: www.archives.anu.edu.au and the National AIDS Archive Collection WATERSIDE WORKERS FEDERATION Deposit No. Z432: Federal Office SITE LIST Receipt Dates Quantity Location 31 Mar 1992 5 cartons and 1 parcel (D1-D5) Stack 294-295 5 May 1992 12 cartons (D6-14) Stack 294-295 27 May 1992 9 cartons & 1 archives box (4-13) Stack 294-295 11 Nov 1992 69 cartons & 1 parcel (14-78) Stack 294-295 21 Dec 1992 2 cartons (80-81- No 79) Stack 294-295 18 May 1993 18 cartons Stack 294-295 13 Jul 1994 2 parcels Stack 294-295 13 Jun/23 Dec 1996 1 bundle (82-86) Stack 294-295 Notes: 31 Mar 1992 5 cartons and 1 parcel of donated ACTU material – circulars and Executive minutes (cartons D1 to D5) 5 May 1992 12 cartons containing donated material – newspaper clippings and ACTU Bulletins and Newsletters (cartons numbered D6 to D14) and copies of Port News in cartons 1-3 (Boxes 1-3) 27 May 1992 9 cartons and 1 archives box containing miscellaneous material, rules, instruction booklets, published histories, circulars and records of N. Docker. Records of CH Fitzgibbon were also sent, but these were removed to his personal collection at P101 (remaining cartons numbered Boxes 4-13) 11 Nov 1992 65 cartons and 1 parcel. -

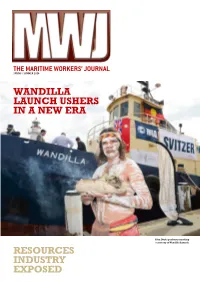

Wandilla Launch Ushers in a New Era Resources

THE MARITIME WORKERS’ JOURNAL SPRING / SUMMER 2014 WANDILLA LAUNCH USHERS IN A NEW ERA Glen Doyle performs smoking ceremony at Wandilla Launch. RESOURCES INDUSTRY EXPOSED p00_Cover.indd 1 19/11/13 9:07 AM CONTENTS 6 - 13 National Council: A meeting of minds 14 & 15 Chevron Campaign: BIS Shrapnel report shows resource industry loose with the truth 22 & 23 Vale Jimmy Tannock: Remembering retired National Deputy Secretary 35 Wandilla Launch: Tugboat signals beginning of new training initiative 41 Credit Union: MMPCU relocates as part of expansion 42 Financial Reports: MUA Concise Financial Report 2013 44 Dispute: Egyptian seafarers have a win in Kembla EDITOR IN CHIEF Paddy Crumlin COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR Jonathan Tasini EDITORIAL TEAM Ashleigh Telford Greig Kelbie DESIGN Magnesium Media PRINTER Printcraft Maritime Workers’ Journal 365-375 Sussex Street Sydney NSW 2000 Contact: 9267 - 9134 Fax: 9261 - 3481 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.mua.org.au MWJ reserves the right at all times to edit and/or reduce any articles or letters to be published. Publication No: 1235 MUA members out in force to celebrate World Maritime Day at the For all story ideas, letters, obituaries please email Australian National Maritime Museum on Darling Harbour. [email protected] LOGGING ON LOGGING ON world economy down the toilet. The company negotiated an EBA without and Port of Convenience campaigns are Who knows really, because the Libs never telling its workforce what it was up to. illustrative of the capacity of international LOGGING had to say anything in opposition? The little Patrick, then, compounded this moral lapse maritime workers to effectively network in time Abbott has been in office doesn’t look by using a type of guerrilla management pursuing justice and accountability in the promising, though. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13804-8 - Labor’s Conflict: Big Business, Workers and the Politics of Class Tom Bramble and Rick Kuhn Frontmatter More information LABOR’S CONFLICT Big business, workers and the politics of class Once widely regarded as the workers’ greatest hope for a better world, the ALP today would rather project itself as a responsible manager of Australian capitalism. Labor’s Conflict: Big Business, Workers and the Politics of Class provides an insightful account of the transformations in the Party’s policies, performance and structures since its formation. Seasoned political analysts Tom Bramble and Rick Kuhn offer an inci- sive appraisal of the Party’s successes and failures, betrayals and electoral triumphs in terms of its competing ties with bosses and workers. The early chapters outline diverse approaches to understanding the nature of the Party and then assess the ALP’s evolution in response to major social upheavals and events, from the strikes of the 1890s, through two World Wars, the Great Depression, and the post-war boom. The records of the Whitlam, Hawke, Keating, Rudd and Gillard governments are then dissected in detail. The compelling conclusion offers alternatives to the Australian Labor Party, for those interested in progressive change. Tom Bramble is Senior Lecturer in Industrial Relations in the School of Business at the University of Queensland. Rick Kuhn is Reader in Political Science in the School of Politics and Inter- national Relations at the Australian National University. © in this web -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

'Not One Pound of Wheat Will Go': Words and Actions

8. ‘Not one pound of wheat will go’: Words and actions The Holstein Express was crewed by Indonesian seamen, but it sailed under a Liberian flag.1 Its Australian agents, Dalgety and Patricks, had been charged with the shipment of 600 dairy cows to Chile. In the week of 4 December 1978, the ship attempted to dock in Newcastle to load but was black banned by Australian workers. Union members would not assist with loading the cargoes. They simply refused. After discussion between the workers’ representatives and the agents, it was agreed that the ship could anchor outside the harbour in Stockton Bight and receive water and stores.2 It remained off Newcastle for two weeks.3 In stop-work meetings on 19 December 1978, the Sydney, Port Kembla, Port Adelaide and Victorian branches of the SUA all passed motions of support for the actions of their Newcastle branch.4 And shortly thereafter a white flag was raised by the owners in the form of a communiqué shown to the maritime unions that the ship would depart for New Zealand without cattle if it was able to refuel. The maritime unions allowed the ship to dock and refuel and it set off on 22 December 1978, apparently without cows and apparently for New Zealand. The company was in the middle of a goosestep that spanned the State. The next day, Don Henderson, secretary of the Firemen and Deckhands’ Union, was urgently advised that the ship was in fact at the southern NSW town of Eden loading hay and cattle.5 The union delegate at Eden was contacted and subsequently the local fishermen who had been hired to load the cattle stopped work.6 The ship’s crew and the vendors were forced to load the cattle themselves and the vessel departed for New Zealand on Sunday, 24 December 1978. -

Corporatism As a Process of Working-Class Containment and Roll-Back: the Recent Experiences of South Africa and South Korea

Corporatism as a process of working-class containment and roll-back: The recent experiences of South Africa and South Korea Tom Bramble School of Business University of Queensland Brisbane Q 4072 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] and Neal Ollett This paper has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Industrial Relations and the final version of this paper will be published in the Journal of Industrial Relations vol. 49, issue 4, September 2007 by Sage Publications Ltd. All rights reserved. © For more information please visit: www.sagepublications.com. ABSTRACT In this article we argue that recent debates in the corporatist literature about whether corporatism is best understood as a process of structured interest representation or political dialogue miss the point as to corporatism’s central task – the shift of material resources and power away from the working class to the capitalist class, in which two processes are evident – containment and roll- back. We discuss these processes in the context of successive waves of corporatism in Western Europe from the 1940s to the 1990s before moving on to an analysis of the contrasting fortunes of corporatism in South Africa and South Korea during democratic transition. We conclude that the ability of corporatism to carry out the processes of containment and roll back in these two cases have been dependent on the existence (or absence) of supportive prior political relationships between organised labour and the state. Corporatism as a process of working-class containment and roll-back: The recent experiences of South Africa and South Korea INTRODUCTION Traditional interpretations of corporatism have focused on institutionalised structures of interest representation (Molina and Rhodes, 2002). -

Full Thesis Draft No Pics

A whole new world: Global revolution and Australian social movements in the long Sixties Jon Piccini BA Honours (1st Class) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of History, Philosophy, Religion & Classics Abstract This thesis explores Australian social movements during the long Sixties through a transnational prism, identifying how the flow of people and ideas across borders was central to the growth and development of diverse campaigns for political change. By making use of a variety of sources—from archives and government reports to newspapers, interviews and memoirs—it identifies a broadening of the radical imagination within movements seeking rights for Indigenous Australians, the lifting of censorship, women’s liberation, the ending of the war in Vietnam and many others. It locates early global influences, such as the Chinese Revolution and increasing consciousness of anti-racist struggles in South Africa and the American South, and the ways in which ideas from these and other overseas sources became central to the practice of Australian social movements. This was a process aided by activists’ travel. Accordingly, this study analyses the diverse motives and experiences of Australian activists who visited revolutionary hotspots from China and Vietnam to Czechoslovakia, Algeria, France and the United States: to protest, to experience or to bring back lessons. While these overseas exploits, breathlessly recounted in articles, interviews and books, were transformative for some, they also exposed the limits of what a transnational politics could achieve in a local setting. Australia also became a destination for the period’s radical activists, provoking equally divisive responses. -

2009 Annual Report 25 Years of Linking Australian Workers with the World Executive Officer’S Report

Union Aid Abroad APHEDA The overseas humanitarian aid agency of the ACTU 2009 Annual Report 25 years of linking Australian workers with the world Executive Officer’s Report Union Aid Abroad – APHEDA was established in 1984 by the ACTU under the name APHEDA (Australian People for Union Aid Abroad – APHEDA Health, Education and Development Abroad) as the Australian union movement’s celebrates 25 years overseas aid arm. We assist projects in South East Asia, the of international solidarity. Pacific, the Middle East and southern Africa, working through local partner organisations and unions to deliver training in vocational skills, health and workers’ rights so women and men may commitment to assisting for workers, especially for have decent work that provides other workers in greater women workers, for a living wage, reasonable need. Their generous disabled youth and for conditions and a safe support is a tribute to their trafficked women. workplace. Our international program seeks to empower belief in justice and a fair go women and men in developing for all. Thanks to donors and countries so they and their partners families might live with their Decent Work essential None of this training is human rights respected, both to overcome poverty possible, of course, without in their workplace and in their society. The ILO, the global union two very special groups of As Union Aid Abroad – movement and the ACTU people – our donors and OUR MISSION APHEDA celebrates 25 all advocate Decent Work our partners. Without the As the ACTU’s humanitarian aid agency, Union Aid Abroad years of international as essential to overcoming generous and growing – APHEDA expresses the solidarity on behalf of the poverty. -

Resisting Howard's Industrial Relations

RESISTING HOWARD’S INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS ‘REFORMS’: AN ASSESSMENT OF ACTU STRATEGY Tom Bramble ‘We are facing the fight of our lives. The trade union movement will be judged on how effectively we meet this challenge’ (AMWU National Secretary, Doug Cameron, May 2005). Howard’s planned industrial relations (IR) legislation confronts Australian unions with their worst nightmare. This is obviously the case for rank and file members who face a savage attack on their conditions, but the legislation is also terrifying for the union bureaucracy. Since Federation, Australian capitalism has operated on the basis of mediating class conflict at the workplace through arbitration and conciliation. This did not mean that class conflict was absent, or that the arbitration system was not itself a weapon in this conflict, only that at the base of any such conflict was a recognition by employers and the state of the legitimacy of the union bureaucracy in the industrial relations process. With its WorkChoices legislation, the Howard government has signalled an onslaught on this entire system and, with it, the central role of union officials in the system of structured class relationships. The purpose of this article is to provide a critical assessment of the strategy drawn up by the ACTU to resist WorkChoices. Although there are differences of emphasis within their ranks, the ACTU executive and office bearers have pursued a strategy with five main components. First, to convince employers that they are wrong to break from the system that has served them well for a century. Second, to lobby the ALP at state and federal levels. -

ANTI-COMMUNISM in TASMANIA in the LATE 1950S with SPECIAL REFERENCE to the HURSEY CASE

ANTI-COMMUNISM IN TASMANIA IN THE LATE 1950s WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE HURSEY CASE Peter D. Jones M.A. (Oxon.), Dip.Ed. (Oxon.) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities December 1995 UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the Thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except when due acknowledgement is made in the text of the Thesis. This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. SYNOPSIS. While the strength of the Democratic Labor Party (DLP) was concentrated in Victoria, Tasmania was also significant for several reasons : it was the electoral base of Senator George Cole, the DLP's leader in the Senate up to 1964; Hobart was the venue of the ALP Federal Conference when the Split occurred in 1955; and it was the only state with a Labor Government throughout the Menzies years. While the Anti-Communist Labour Party, later the DLP, contested all State and Federal elections after 1956, they failed to make significant inroads into the ALP vote, although Senator George Cole (first elected on the ALP ticket in 1949) was able to maintain his Senate seat until 1964 - largely because of the Tasmanian tradition of voting for personalities rather than ideologies. The DLP vote in both State and Federal elections failed to affect the overall results, except in the 1959 state election, when DLP preferences in Franklin gave an extra unexpected extra seat to the Liberal Party and resulted in a situation where two Independents held the balance of power. -

The Rise and Fall of Australian Maoism

The Rise and Fall of Australian Maoism By Xiaoxiao Xie Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Studies School of Social Science Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide October 2016 Table of Contents Declaration II Abstract III Acknowledgments V Glossary XV Chapter One Introduction 01 Chapter Two Powell’s Flowing ‘Rivers of Blood’ and the Rise of the ‘Dark Nations’ 22 Chapter Three The ‘Wind from the East’ and the Birth of the ‘First’ Australian Maoists 66 Chapter Four ‘Revolution Is Not a Dinner Party’ 130 Chapter Five ‘Things Are Beginning to Change’: Struggles Against the turning Tide in Australia 178 Chapter Six ‘Continuous Revolution’ in the name of ‘Mango Mao’ and the ‘death’ of the last Australian Maoist 220 Conclusion 260 Bibliography 265 I Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968.