Callicarpa Americana L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA Spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION for COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE By Ana Maria Metaxas Approved: James Hill Craddock Jennifer Boyd Professor of Biological Sciences Assistant Professor of Biological and Environmental Sciences (Director of Thesis) (Committee Member) Gregory Reighard Jeffery Elwell Professor of Horticulture Dean, College of Arts and Sciences (Committee Member) A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of the Graduate School CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE by Ana Maria Metaxas A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science May 2013 ii ABSTRACT Chestnut cultivars were evaluated for their commercial applicability under the environmental conditions in Hamilton County, TN at 35°13ꞌ 45ꞌꞌ N 85° 00ꞌ 03.97ꞌꞌ W elevation 230 meters. In 2003 and 2004, 534 trees were planted, representing 64 different cultivars, varieties, and species. Twenty trees from each of 20 different cultivars were planted as five-tree plots in a randomized complete block design in four blocks of 100 trees each, amounting to 400 trees. The remaining 44 chestnut cultivars, varieties, and species served as a germplasm collection. These were planted in guard rows surrounding the four blocks in completely randomized, single-tree plots. In the analysis, we investigated our collection predominantly with the aim to: 1) discover the degree of acclimation of grower- recommended cultivars to southeastern Tennessee climatic conditions and 2) ascertain the cultivars’ ability to survive in the area with Cryphonectria parasitica and other chestnut diseases and pests present. -

New Species and Combinations of Apocynaceae, Bignoniaceae, Clethraceae, and Cunoniaceae from the Neotropics

Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid 75 (2): e071 https://doi.org/10.3989/ajbm.2499 ISSN: 0211-1322 [email protected], http://rjb.revistas.csic.es/index.php/rjb Copyright: © 2018 CSIC. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial (by-nc) Spain 4.0 License. New species and combinations of Apocynaceae, Bignoniaceae, Clethraceae, and Cunoniaceae from the Neotropics Juan Francisco Morales 1,2,3 1 Missouri Botanical Garden 4344 Shaw Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63110, USA. 2 Bayreuth Center of Ecology and Environmental Research (BayCEER), University of Bayreuth, Universitätstrasse 30, 95447 Bayreuth, Germany. 3 Doctorado en Ciencias Naturales para el Desarrollo (DOCINADE), Universidad Estatal a Distancia, 474–2050 Montes de Oca, Costa Rica. [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8906-8567 Abstract. Mandevilla arenicola J.F.Morales sp. nov. from Brazil, Clethra Resumen. Se describen e ilustran Mandevilla arenicola J.F.Morales secazu J.F.Morales sp. nov. from Costa Rica, and Weinmannia abstrusa sp. nov. de Brasil, Clethra secazu J.F.Morales sp. nov. de Costa Rica y J.F.Morales sp. nov. from Honduras are described and illustrated and Weinmannia abstrusa J.F.Morales sp. nov. de Honduras y se discuten their relationships with morphologically related species are discussed. sus relaciones con otras especies de morfología semejante. Se designan Lectotypes are designated for Anemopaegma tonduzianum Kraenzl., lectotipos para Anemopaegma tonduzianum Kraenzl., Bignonia Bignonia sarmentosa var. hirtella Benth. and Paragonia pyramidata var. sarmentosa var. hirtella Benth. and Paragonia pyramidata var. tomentosa tomentosa Bureau & K. Schum., as well as these last two names have Bureau & K.Schum., así como también se combinan estos dos últimos been combined. -

Integration of Entomopathogenic Fungi Into IPM Programs: Studies Involving Weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) Affecting Horticultural Crops

insects Review Integration of Entomopathogenic Fungi into IPM Programs: Studies Involving Weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) Affecting Horticultural Crops Kim Khuy Khun 1,2,* , Bree A. L. Wilson 2, Mark M. Stevens 3,4, Ruth K. Huwer 5 and Gavin J. Ash 2 1 Faculty of Agronomy, Royal University of Agriculture, P.O. Box 2696, Dangkor District, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 2 Centre for Crop Health, Institute for Life Sciences and the Environment, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Queensland 4350, Australia; [email protected] (B.A.L.W.); [email protected] (G.J.A.) 3 NSW Department of Primary Industries, Yanco Agricultural Institute, Yanco, New South Wales 2703, Australia; [email protected] 4 Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation (NSW Department of Primary Industries and Charles Sturt University), Wagga Wagga, New South Wales 2650, Australia 5 NSW Department of Primary Industries, Wollongbar Primary Industries Institute, Wollongbar, New South Wales 2477, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +61-46-9731208 Received: 7 September 2020; Accepted: 21 September 2020; Published: 25 September 2020 Simple Summary: Horticultural crops are vulnerable to attack by many different weevil species. Fungal entomopathogens provide an attractive alternative to synthetic insecticides for weevil control because they pose a lesser risk to human health and the environment. This review summarises the available data on the performance of these entomopathogens when used against weevils in horticultural crops. We integrate these data with information on weevil biology, grouping species based on how their developmental stages utilise habitats in or on their hostplants, or in the soil. -

The American Chestnut

Historic, Archive Document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. United States Department of Agriculture the American National Agricultural Library Chestnut: A Bibliography. State University of New York Geneseo Bibliographies and Literature of Agriculture Number 103 949140 United States Department of Agriculture The American National Agricultural Library Chestnut: J Agricultural Library A Bibliography State University Of New York A bibliography of references to Castanea dentata and other Geneseo chestnut species, and on Chestnut Blight and its causal pathogen of the fungal genus Endothia or Cryphonectria. By Bibliographies and Literature of Agriculture Herman S. Forest Number 103 State University of New York September 1 990 Geneseo Richard J. Cook Rochester, NY and Charles N. Bebee National Agricultural Library National Agricultural Library Beltsville, Maryland 1990 National Agricultural Library Cataloging Record: Forest, Herman S. The American chestnut : a bibliography of references to Castanea dentata and other chestnut species, and on chestnut blight and its causal pathogen of the fungal genus Endothia or Cryphonectria. (Bibliographies and literature of agriculture ; no. 103) 1. American chestnut — Bibliography. 2. Endothia parasitica — Bibliography. I. Cook, Richard J. II. Bebee, Charles N. III. Title. aZ5076.AlU54 no. 103 CONTENTS Dedication and Acknowledgments iv Preface v Key to References, Base List 1 Base Reference List 6 List Two, Key to References • 87 References, List Two 91 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We owe thanks to Jean Quinn Wade, who started with Dick Cook's collection of file cards and all manner of disorderly references given her over a 10-year period. Out of these she standardized, organized, and typed the preliminary edition of this bibliography (1986). -

Native Plants for Your Backyard

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Native Plants for Your Backyard Native plants of the Southeastern United States are more diverse in number and kind than in most other countries, prized for their beauty worldwide. Our native plants are an integral part of a healthy ecosystem, providing the energy that sustains our forests and wildlife, including important pollinators and migratory birds. By “growing native” you can help support native wildlife. This helps sustain the natural connections that have developed between plants and animals over thousands of years. Consider turning your lawn into a native garden. You’ll help the local environment and often use less water and spend less time and money maintaining your yard if the plants are properly planted. The plants listed are appealing to many species of wildlife and will look attractive in your yard. To maximize your success with these plants, match the right plants with the right site conditions (soil, pH, sun, and moisture). Check out the resources on the back of this factsheet for assistance or contact your local extension office for soil testing and more information about these plants. Shrubs Trees Vines Wildflowers Grasses American beautyberry Serviceberry Trumpet creeper Bee balm Big bluestem Callicarpa americana Amelanchier arborea Campsis radicans Monarda didyma Andropogon gerardii Sweetshrub Redbud Carolina jasmine Fire pink Little bluestem Calycanthus floridus Cercis canadensis Gelsemium sempervirens Silene virginica Schizachyrium scoparium Blueberry Red buckeye Crossvine Cardinal flower -

Landscape Vines for Southern Arizona Peter L

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AZ1606 October 2013 LANDSCAPE VINES FOR SOUTHERN ARIZONA Peter L. Warren The reasons for using vines in the landscape are many and be tied with plastic tape or plastic covered wire. For heavy vines, varied. First of all, southern Arizona’s bright sunshine and use galvanized wire run through a short section of garden hose warm temperatures make them a practical means of climate to protect the stem. control. Climbing over an arbor, vines give quick shade for If a vine is to be grown against a wall that may someday need patios and other outdoor living spaces. Planted beside a house painting or repairs, the vine should be trained on a hinged trellis. wall or window, vines offer a curtain of greenery, keeping Secure the trellis at the top so that it can be detached and laid temperatures cooler inside. In exposed situations vines provide down and then tilted back into place after the work is completed. wind protection and reduce dust, sun glare, and reflected heat. Leave a space of several inches between the trellis and the wall. Vines add a vertical dimension to the desert landscape that is difficult to achieve with any other kind of plant. Vines can Self-climbing Vines – Masonry serve as a narrow space divider, a barrier, or a privacy screen. Some vines attach themselves to rough surfaces such as brick, Some vines also make good ground covers for steep banks, concrete, and stone by means of aerial rootlets or tendrils tipped driveway cuts, and planting beds too narrow for shrubs. -

Bignoniaceae)

Systematic Botany (2007), 32(3): pp. 660–670 # Copyright 2007 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists Taxonomic Revisions in the Polyphyletic Genus Tabebuia s. l. (Bignoniaceae) SUSAN O. GROSE1 and R. G. OLMSTEAD Department of Biology, University of Washington, Box 355325, Seattle, Washington 98195 U.S.A. 1Author for correspondence ([email protected]) Communicating Editor: James F. Smith ABSTRACT. Recent molecular studies have shown Tabebuia to be polyphyletic, thus necessitating taxonomic revision. These revisions are made here by resurrecting two genera to contain segregate clades of Tabebuia. Roseodendron Miranda consists of the two species with spathaceous calices of similar texture to the corolla. Handroanthus Mattos comprises the principally yellow flowered species with an indumentum of hairs covering the leaves and calyx. The species of Handroanthus are also characterized by having extremely dense wood containing copious quantities of lapachol. Tabebuia is restricted to those species with white to red or rarely yellow flowers and having an indumentum of stalked or sessile lepidote scales. The following new combinations are published: Handroanthus arianeae (A. H. Gentry) S. Grose, H. billbergii (Bur. & K. Schum). S. Grose subsp. billbergii, H. billbergii subsp. ampla (A. H. Gentry) S. Grose, H. botelhensis (A. H. Gentry) S. Grose, H. bureavii (Sandwith) S. Grose, H. catarinensis (A. H. Gentry) S. Grose, H. chrysanthus (Jacq.) S. Grose subsp. chrysanthus, H. chrysanthus subsp. meridionalis (A. H. Gentry) S. Grose, H. chrysanthus subsp. pluvicolus (A. H. Gentry) S. Grose, H. coralibe (Standl.) S. Grose, H. cristatus (A. H. Gentry) S. Grose, H. guayacan (Seemann) S. Grose, H. incanus (A. H. -

The Effect of Insects on Seed Set of Ozark Chinquapin, Castanea Ozarkensis" (2017)

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 The ffecE t of Insects on Seed Set of Ozark Chinquapin, Castanea ozarkensis Colton Zirkle University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Botany Commons, Entomology Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Zirkle, Colton, "The Effect of Insects on Seed Set of Ozark Chinquapin, Castanea ozarkensis" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1996. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1996 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. The Effect of Insects on Seed Set of Ozark Chinquapin, Castanea ozarkensis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology by Colton Zirkle Missouri State University Bachelor of Science in Biology, 2014 May 2017 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________________ Dr. Ashley Dowling Thesis Director ____________________________________ ______________________________________ Dr. Frederick Paillet Dr. Neelendra Joshi Committee Member Committee Member Abstract Ozark chinquapin (Castanea ozarkensis), once found throughout the Interior Highlands of the United States, has been decimated across much of its range due to accidental introduction of chestnut blight, Cryphonectria parasitica. Efforts have been made to conserve and restore C. ozarkensis, but success requires thorough knowledge of the reproductive biology of the species. Other Castanea species are reported to have characteristics of both wind and insect pollination, but pollination strategies of Ozark chinquapin are unknown. -

Bignonieae: Bignoniaceae) and Their Contribution to the Systematics of the Group

Botanical Sciences 90 (1): 13-20 BOTÁNICA ESTRUCTURAL VARIATION IN THE TRACHEOIDS OF SEEDS FROM THE SUBTRIBE PITHECOCTENIINAE (BIGNONIEAE: BIGNONIACEAE) AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO THE SYSTEMATICS OF THE GROUP CARLOS MANUEL BURELO-RAMOS1, FRANCISCO GERARDO LOREA-HERNÁNDEZ2 3, 4 AND GUILLERMO ANGELES 1Herbario UJAT, División Académica de Ciencias Biológicas. Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco 2Instituto de Ecología, A.C. Red de Biodiversidad y Sistemática 3Instituto de Ecología, A.C., Red de Ecología Funcional 4Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: The diversity of ornamentations present in the tracheoids of seed surface from species of the subtribe Pithecocteniinae (genera Amphilophium, Distictella, Distictis, Glaziovia, Haplolophium, and Pithecoctenium) in the Bignoniaceae is described. Three distinct ornamentation types were observed on the tracheoid surfaces: (1) Tracheoids without ornaments (in the genera Am- philophium, Glaziovia and Haplolophium), (2) ornaments in true helices (in the genera Distictis and Distictella), and (3) ornaments in pseudo-helices (in the genus Pithecoctenium). The taxonomic value of these tracheoid ornaments to establish possible relationships within the subtribe Pithecocteniinae is discussed. Key words: Bignoniaceae, cell-wall thickening, Pithecocteniinae, tracheoids, winged seeds. Resumen: Se describe la diversidad de ornamentaciones presentes en los traqueoides de las semillas de especies de la subtribu Pithecocteniinae (Bignoniaceae), la cual incluye a los géneros Amphilophium, Distictella, Distictis, Glaziovia, Haplolophium y Pithecoctenium. Se observaron tres tipos de ornamentación sobre las superficies de los traqueoides: (1) Traqueoides sin ornamen- taciones en tres géneros (Amphilophium, Glaziovia y Haplolophium), (2) ornamentaciones formando hélices verdaderas (en los géneros Distictis y Distictella) y (3) ornamentaciones en pseudo-hélices (en el género Pithecoctenium). -

Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping Chesapeake Bay Watershed Acknowledgments

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping Chesapeake Bay Watershed Acknowledgments Contributors: Printing was made possible through the generous funding from Adkins Arboretum; Baltimore County Department of Environmental Protection and Resource Management; Chesapeake Bay Trust; Irvine Natural Science Center; Maryland Native Plant Society; National Fish and Wildlife Foundation; The Nature Conservancy, Maryland-DC Chapter; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center; and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office. Reviewers: species included in this guide were reviewed by the following authorities regarding native range, appropriateness for use in individual states, and availability in the nursery trade: Rodney Bartgis, The Nature Conservancy, West Virginia. Ashton Berdine, The Nature Conservancy, West Virginia. Chris Firestone, Bureau of Forestry, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Chris Frye, State Botanist, Wildlife and Heritage Service, Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Mike Hollins, Sylva Native Nursery & Seed Co. William A. McAvoy, Delaware Natural Heritage Program, Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Mary Pat Rowan, Landscape Architect, Maryland Native Plant Society. Rod Simmons, Maryland Native Plant Society. Alison Sterling, Wildlife Resources Section, West Virginia Department of Natural Resources. Troy Weldy, Associate Botanist, New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Graphic Design and Layout: Laurie Hewitt, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office. Special thanks to: Volunteer Carole Jelich; Christopher F. Miller, Regional Plant Materials Specialist, Natural Resource Conservation Service; and R. Harrison Weigand, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Maryland Wildlife and Heritage Division for assistance throughout this project. -

Lamiales – Synoptical Classification Vers

Lamiales – Synoptical classification vers. 2.6.2 (in prog.) Updated: 12 April, 2016 A Synoptical Classification of the Lamiales Version 2.6.2 (This is a working document) Compiled by Richard Olmstead With the help of: D. Albach, P. Beardsley, D. Bedigian, B. Bremer, P. Cantino, J. Chau, J. L. Clark, B. Drew, P. Garnock- Jones, S. Grose (Heydler), R. Harley, H.-D. Ihlenfeldt, B. Li, L. Lohmann, S. Mathews, L. McDade, K. Müller, E. Norman, N. O’Leary, B. Oxelman, J. Reveal, R. Scotland, J. Smith, D. Tank, E. Tripp, S. Wagstaff, E. Wallander, A. Weber, A. Wolfe, A. Wortley, N. Young, M. Zjhra, and many others [estimated 25 families, 1041 genera, and ca. 21,878 species in Lamiales] The goal of this project is to produce a working infraordinal classification of the Lamiales to genus with information on distribution and species richness. All recognized taxa will be clades; adherence to Linnaean ranks is optional. Synonymy is very incomplete (comprehensive synonymy is not a goal of the project, but could be incorporated). Although I anticipate producing a publishable version of this classification at a future date, my near- term goal is to produce a web-accessible version, which will be available to the public and which will be updated regularly through input from systematists familiar with taxa within the Lamiales. For further information on the project and to provide information for future versions, please contact R. Olmstead via email at [email protected], or by regular mail at: Department of Biology, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195, USA. -

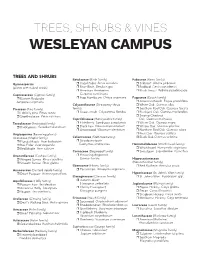

Trees, Shrubs & Vines

TREES, SHRUBS & VINES WESLEYAN CAMPUS TREES AND SHRUBS Betulaceae (Birch family) Fabaceae (Bean family) Gymnosperms r Hazel Alder Alnus serrulata r Silktree† Albizia julibrissin (plants with naked seeds) r River Birch Betula nigra r Redbud Cercis canadensis r American Hornbeam r Black Locust Robinia pseudoacacia Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Carpinus caroliniana r Eastern Redcedar r Hop-Hornbeam Ostrya virginiana Fagaceae (Beech family) Juniperus virginiana r American Beech Fagus grandifolia Calycanthaceae (Strawberry-shrub r White Oak Quercus alba Pinaceae (Pine family) family) r Southern Red Oak Quercus falcata r Loblolly pine Pinus taeda r Sweet-shrub Calycanthus floridus r Blackjack Oak Quercus marilandica r Shortleaf pine Pinus echinata r Swamp Chestnut Caprifoliaceae (Honeysuckle family) Oak Quercus michauxii Taxodiaceae (Redwood family) r Elderberry Sambucus canadensis r Water Oak Quercus nigra r Baldcypress Taxodium distichum r Black haw Viburnum prunifolium r Willow Oak Quercus phellos r Arrowwood Viburnum dentatum r Northern Red Oak Quercus rubra Angiosperms (flowering plants) r Post Oak Quercus stellata Aceraceae (Maple family) Celastraceae (Staff-tree family) r Black Oak Quercus velutina r Florida Maple Acer barbatum r Strawberry bush r Box Elder Acer negundo Euonymus americanus Hamamelidaceae (Witch hazel family) r Red Maple Acer rubrum r Witch hazel Hamamelis virginiana Cornaceae (Dogwood family) r Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Anacardiaceae (Cashew family) r Flowering dogwood r Winged Sumac Rhus copallina Cornus florida Hippocastanaceae r Smooth Sumac Rhus glabra (Horsechestnut family) Ebenaceae (Ebony family) r Red Buckeye Aesculus pavia Annonaceae (Custard Apple family) r Persimmon Diospyros virginiana r Dwarf Pawpaw Asimina parviflora Hypericaceae (St. John’s-Wort family) Elaeagnaceae (Oleaster family) r St.