The Importance of Import Substitution in Marathon Economic Impact Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honolulu Marathon Media Guide 2017

HONOLULU MARATHON MEDIA GUIDE 2017 © HONOLULU MARATHON 3435 Waialae Avenue, Suite 200 • Honolulu, HI 96816 USA • Phone: (808) 734-7200 • Fax: (808) 732-7057 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.honolulumarathon.org 2017 Honolulu Marathon Media Guide MEDIA INFORMATION 3 MEDIA TEAM 3 MEDIA CENTER ONLINE 3 MEDIA OFFICE 3 ATHLETE PHOTO CALL 3 LIVE RACE DAY COVERAGE 3 POST RACE PRESS CONFERENCE 4 CHAMPIONS AUTOGRAPH SESSION 4 ACCREDITATION 4 SOCIAL MEDIA 4 RESULTS 4 IMAGE LIBRARY 5 2017 HONOLULU MARATHON GENERAL INFORMATION 7 ELITE FIELD 10 HTTP://WWW.HONOLULUMARATHON.ORG/MEDIA-CENTER/ELITE-RUNNERS/ 13 PRIZE MONEY 13 TIME BONUS 14 COURSE RECORDS 14 CHAMPIONS 1973-2016 14 2016 HONOLULU MARATHON IN NUMBERS 15 MARATHON HISTORY: 1973-2016 16 ENTRANTS AND FINISHERS 16 MARATHON ENTRANTS FROM JAPAN 1973 – 2016 18 ECONOMIC IMPACT (2005-2011) 19 TRIVIA IN NUMBERS 21 WHAT IT TAKES TO CONDUCT A WORLD-CLASS MARATHON 21 HONOLULU MARATHON page 2 of 21 2017 Honolulu Marathon Media Guide Media Information Media team Fredrik Bjurenvall 808 - 225 7599 [email protected] Denise van Ryzin 808 – 258 2209 David Monti 917 - 385 2666 [email protected] Taylor Dutch [email protected] Media Center Online https://www.honolulumarathon.org/media-center Media office We are located in the Hawaii Convention Center, room 306 during race week (December 07-09). On race day, Sunday December 10, we will be in the Press Tent next to the finish line in Kapiolani Park. Athlete Photo Call All elite athletes will convene for interviews and a photo call: Time: 1pm Friday December 8. -

DECEMBER 2010 NEWSLETTER Volume 7, Number 9

DECEMBER 2010 NEWSLETTER Volume 7, Number 9 NEWSLETTER CONTENTS Great Santa Run 2 Half Fanatics 2 Rock N Roll Las Vegas Marathon 3-4 2010 Year in Review 6 Titanium Maniacs 7 Honolulu Marathon 8-9 Pigtails Run 10 Happy Holidays from the Chicago Maniacs 11 Report from InSane AsyLum 11 Maniac Poll 12 Jacksonville Marathon 13 Social Networking 13 Promotions 14 Coming Up in January 15 Operation Jack Finale 16 New Maniacs 17 Discounts 18 Note from the Editor 19 Rhetorical Revelations from “The Rev” 20 A fun and festive December with the Maniacs!! Larry Macon and Yolanda Holder once again take home the top honors as Maniac of the Year. This time they each set the world record with 106 marathons in 2010! December 2010 Newsletter Angie Whitworth-Pace Tory Klementsen Marathon Maniacs running half marathons… YES, it’s true! Tired of running marathons and ultras (HA!!)? Need to back down on that weekly mileage and concentrate on getting faster? Then join the Half Fanatics (halffanatics.com). There are currently over 700 members in the Fanatic Asylum, and I’m sure you’ll recognize a few names in the group. So jump on the bandwagon now, get your qualifying races in These are just a few of the hundreds of Half Fanatics! and join this new, zany group! Okay now back to your regular scheduled Maniac newsletter… www.halffanatics.com 2 December 2010 Newsletter A collision of Maniacs and Fanatics in Sin City. Les Omura Noel Lazaro Garibay Sue Mantyla Elizabeth Culver Rick Deaver Anita Dabrowska 3 December 2010 Newsletter Jonathan Young Kino Dale Roberts Yolanda -

Hālāwai Papa Alakaʻi Kūmau Keʻena Kuleana Hoʻokipa O Hawaiʻi Hālāwai Kino a Kikohoʻe In-Person and Virtual Regular

HĀLĀWAI PAPA ALAKAʻI KŪMAU KEʻENA KULEANA HOʻOKIPA O HAWAIʻI HĀLĀWAI KINO A KIKOHOʻE IN-PERSON AND VIRTUAL REGULAR BOARD MEETING HAWAI‘I TOURISM AUTHORITY Pōʻahā, 24 Iune 2021, 9:30 a.m. Thursday, June 24, 2021 at 9:30 a.m. Kikowaena Hālāwai O Hawaiʻi Hawaiʻi Convention Center Papahele ʻEhā | Lumi Nui C Fourth Floor | Ballroom C 1801 Alaākea Kalākaua 1801 Kalākaua Avenue Honolulu, Hawaiʻi 96815 Honolulu, Hawaiʻi 96815 ʻO ka hoʻopakele i ke ola o ka lehulehu ka makakoho The safety of the public is of the utmost nui. E maliu ana ke keʻena i ke kuhikuhina a nā loea no importance. Pursuant to expert guidance, HTA will ke kū kōwā, ka uhi maka, me nā koina pili olakino ʻē be following strict physical distancing, facial aʻe. Koi ʻia ke komo i ka uhi maka a me ke kū kōwā ma coverings, and other health-related requirements. nā keʻena a ma nā hālāwai. Face coverings and physical distancing are required in HTA offices and meetings. Koi ʻia ka hōʻoia i kou olakino maikaʻi ma mua o ke Entrance to the Hawaiʻi Convention Center requires komo i ke Kikowaena Hālāwai O Hawaiʻi ma ka ʻīpuka o a health screening at the center parking garage waena o ka hale hoʻokū kaʻa. E pāpā ʻia ke komo ʻana o entrance. Persons with a temperature of over ke kanaka nona ka piwa ma luna aʻe o ka 100.4°F. Inā 100.4°F will be denied entry. If you are not feeling ʻōmaʻimaʻi ʻoe, e ʻoluʻolu, e ʻimi i ke kauka nāna e well, we urge you to contact a healthcare provider. -

Table of Contents

Media Table of contents Media information & fast facts ......................................................................................................... 3 Important media information ....................................................................................................................................................4 Race week Media Center..............................................................................................................................................................4 Race week schedule of events ..................................................................................................................................................7 Quick Facts ...........................................................................................................................................................................................8 Top storylines ......................................................................................................................................................................................10 Prize purse .............................................................................................................................................................................................13 Time bonuses ......................................................................................................................................................................................14 Participant demographics ............................................................................................................................................................15 -

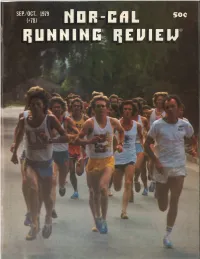

Norcal Running Review

UCLA, and just graduated from San Mateo High. Tom is primarily 'Dunc' showed them all that he was in record shape anyway with a cross-country runner but wants to run in several marathons in an 8:19+ (two miles) just after the Games. Then the biggie... the near future. Bob Hertan (26), 8043 Greenridge Dr., #11, an American record 13:19.4 in Sweden at an international meet. Oakland 94605 (Ph. 638-6220) is currently working on his Mas This time bettered Steve Prefontaine's mark of 13:22.8. Al ters in Physical Education & Kinesiology at Cal-State Hayward. though Dunc has paid his dues for the year, the time won't Bob runs well at most distances from the 100 thru the middle count as a club record because he competes for the Mid-Pacific distances. His PR's include: 9.9, 21.6 (21.OR), 49.0 (48.5R), Road Runners (Hawaii) during the year. See the cover shot of and 1:54. He has also done 1-1/2 miles in 6:37. With his na Dunc, taken at the Trials. Don Kardong, ex-WVTC'er now com tural speed and ability to run longer distances, Bob could be a peting for Club Northwest, was nothing but impressive in the 'class' 880-mile runner in the future. Kenneth McRae (33), Olympic Games Marathon as he grabbed an unexpected fourth, on 27525 Tyrrell Ave., #3, Hayward 94544 (Ph. 782-9458) works as a ly a few seconds out of third place. He set a PR of 2:11:15, Federal Employee and has been a familiar face at local races on finishing only 30 seconds behind Shorter and 1:20 out of the the LDR schedule this year. -

Honolulu Marathon Media Guide 2019

HONOLULU MARATHON MEDIA GUIDE 2019 © HONOLULU MARATHON 3435 Waialae Avenue, Suite 200 • Honolulu, HI 96816 USA • Phone: (808) 734-7200 • Fax: (808) 732-7057 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.honolulumarathon.org 2019 Honolulu Marathon Media Guide Media Information Media team Fredrik Bjurenvall 808 - 225 7599 [email protected] Denise Van Ryzin 808 - 258 2209 David Monti 917 - 385 2666 [email protected] Taylor Dutch 951-847 1289 [email protected] Media Center Online https://www.honolulumarathon.org/media-center Media office We are located in the Hawaii Convention Center, room 306 during race week (December 5-7). See Accreditation section for hours. On race day, Sunday December 8, we will be in the Press Tent next to the finish line in Kapiolani Park. Athlete Photo Call All elite athletes will convene for interviews and a photo call: Time: 1pm Friday December 6. Place: Outrigger Reef on the Beach Hotel – near lobby Live Race Day Coverage KITV – ABC TV affiliate: http://www.kitv.com The official marathon broadcast will feature Robert Kekaula, Toni Reavis and Todd Iacovelli in the studio with live broadcast units reporting from the course. Radio - KSSK 92.3 Hawaii : 5am – 7am (Direct Link to feed) Post Race Press Conference Immediately after the male winner finishes. Approx Time: 7:30am Convene at 7am just outside Press Tent. HONOLULU MARATHON page 2 of 13 2019 Honolulu Marathon Media Guide Champions Autograph Session Male and female champions will sign autographs for the general public on Monday December 9 Place: Hawaii Convention Center, by Certificate Pick Up Time: 9am, Monday, December 9 Accreditation All media are asked to pre register for accreditation online at: https://www.honolulumarathon.org/media-accreditation Accreditation of all press will take place at the Media office during normal expo hours: • Thursday, December 5, 9AM-6PM • Friday, December 6, 9AM-7PM • Saturday, December 7, 10AM-1PM For accreditation we require proof of affiliation and valid id. -

Share the Story of Your First Marathon! See Page 8 Shawna Thompkins

Volume 8, Number 8 NEWSLETTER CONTENTS White River 50 2 Park City Marathon 3 Half Fanatics 3 First Call Summer Marathon 4-5 Social Networking 5 Maniac Art #2 6 ET Midnight Marathon 7 My First Marathon! 8-9 Beast of Burden 10 Maniac Poll 10 Marathon Show Marathon II 11 Cascade Crest 100 12 Report from InSane AsyLum 13 Promotions 14 Coming Up in August 15 New Maniacs 16 Note from the Editor 17 Discounts 18 Rhetorical Revelations from “The Rev” 19 Share the story of your first marathon! See Page 8 Shawna Thompkins White River 50 (7/30): Jenny Appel, *Hotrod*, Eric Barnes, Tracy Brown, Carsten Buus, Francesca Carmichael, Kevin "Captain" Carrothers, Paul Grove, Matt "Pooky" Hagen, Francie Hankins, Bob Hearn, Rob "Rattler" Hester, Genia "Tiptoes" Kacey, Dean Kayler, Scott Krell, Ashley "rogue wave" Kuhlmann, LoneWolf, Deby Kumasaka, Sonny "Tranquilrunner" LaForm, Stevie Ray Lopez, Mike Mahanay, Sara Malcolm, King Arthur Martineau, Janice Moyer, Bob 'BobO" OBrien, Ryan Ordway, Kristin Parker, Cliff "quack, quack" Richards, EatDrinkRunWoman, Rob Stretz, Karen"Evil Twin" Vollan, Francine Weigeldt, Karen Wiggins Rob Stretz Cliff Richards Ashley Kuhlmann Daniel Kuhlmann Mike Mahanay Sonny LaForm Bill Barmore http://www.marathonmaniacs.com 2 Sue Mantyla Teresa Baker Park City Marathon (8/20): Teresa Baker, Tomer Benyair, John Bozung, Earl Fulcher, Galen Garrison, Liz Gotter, Scott Hardy, Ted Hobart, Steve Kissell, Franz Kolb, Stevie Ray Lopez, Vincent Ma, Bill Mandler, Sue "Italian Stallion" Mantyla, John Oster, Laurie Osterberg, Blaine Phillips, Angie Whitworth Pace Vincent, Sue and Angie Angie Whitworth Pace and Galen Garrison Larry Macon and Vincent Ma Marathon Maniacs running half Elaine Green marathons… HALF-MARATHON CRAZY YES, it’s true! Tired of running marathons and ultras (HA!!)? Need to back down on that weekly mileage and concentrate on getting faster? Then join the Half Fanatics (halffanatics.com). -

100 Marathon Club Roster 08-01-20

100 MARATHON CLUB NORTH AMERICA Founded March 31, 2001 by Bob and Lenore Dolphin MEMBERSHIP ROSTER Updated: August 1, 2020 ! Director: Ron Fowler EMail roster updates to: [email protected] NOTICE: Given the on-going, worldwide Covid-19 pandemic, we are suspending updating of the club's on-line roster and production of the monthly newsletter. Ron Fowler, August 1, 2020 NAME ST CITY AGE M # EVENT LOCATION DATE ACHIEVEMENTS Adair, Tom GA Alpharetta 68 1 Atlanta Marathon Atlanta, GA 11/19/1994 Past President 50 States Marathon Club 100 Atlanta Marathon Atlanta, GA 11/23/2000 Past VP 100 Marathon Club – Japan 200 Hot to Trot 8 Hour Run Atlanta, GA 8/6/2005 7 continents finisher 300 Darkside Marathon Peachtree City, GA 5/25/2009 3 time 50 states finisher 11-2008 in DE Raced 149 consecutive months 1995-2008 Total = 308 marathons as of 12-31-13 Adams, Ron BC North 65 1 Vancouver International Vancouver, BC 5/3/1981 Completed 6 ironman triathlons, Western Vancouver 100 Diez Vista 50K Coquitlam, BC 4/7/2007 States 100 Mile, Knee Knackering North Shore Trail Run 23 times (tied for most) Race director Whistler 50 Mile Ultra PR 2:49:03 set in 1990 at age 41 Aguirre, Andrew OK Tulsa 37 1 Route 66 Marathon Tulsa, OK 11/21/2010 50 states & DC finisher 2017 Honolulu 100 Honolulu Marathon Honolulu, HI 12/10/2017 PR 4:02:30 set in 2015 at age 35 Current total = 77 marathons and 23 ultras Aldous, David CO Denver 59 1 Houston Marathon Houston, TX 1/15/1995 50 states & DC finisher 2015 Maui 100 Salt Lake City Marathon Salt Lake City, UT 4/18/2015 PR 3:51 set in 1996 at age 39 Allen, Herb WA Bainbridge 71 1 Island 100 Yakima River Canyon M. -

2021 : RRCA Distance Running Hall of Fame : 1971 RRCA DISTANCE RUNNING HALL of FAME MEMBERS

2021 : RRCA Distance Running Hall of Fame : 1971 RRCA DISTANCE RUNNING HALL OF FAME MEMBERS 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 Bob Cambell Ted Corbitt Tarzan Brown Pat Dengis Horace Ashenfleter Clarence DeMar Fred Faller Victor Drygall Leslie Pawson Don Lash Leonard Edelen Louis Gregory James Hinky Mel Porter Joseph McCluskey John J. Kelley John A. Kelley Henigan Charles Robbins H. Browning Ross Joseph Kleinerman Paul Jerry Nason Fred Wilt 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 R.E. Johnson Eino Pentti John Hayes Joe Henderson Ruth Anderson George Sheehan Greg Rice Bill Rodgers Ray Sears Nina Kuscsik Curtis Stone Frank Shorter Aldo Scandurra Gar Williams Thomas Osler William Steiner 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 Hal Higdon William Agee Ed Benham Clive Davies Henley Gabeau Steve Prefontaine William “Billy” Mills Paul de Bruyn Jacqueline Hansen Gordon McKenzie Ken Young Roberta Gibb- Gabe Mirkin Joan Benoit Alex Ratelle Welch Samuelson John “Jock” Kathrine Switzer Semple Bob Schul Louis White Craig Virgin 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 Nick Costes Bill Bowerman Garry Bjorklund Dick Beardsley Pat Porter Ron Daws Hugh Jascourt Cheryl Flanagan Herb Lorenz Max Truex Doris Brown Don Kardong Thomas Hicks Sy Mah Heritage Francie Larrieu Kenny Moore Smith 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 Barry Brown Jeff Darman Jack Bacheler Julie Brown Ann Trason Lynn Jennings Jeff Galloway Norm Green Amby Burfoot George Young Fred Lebow Ted Haydon Mary Decker Slaney Marion Irvine 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Ed Eyestone Kim Jones Benji Durden Gerry Lindgren Mark Curp Jerry Kokesh Jon Sinclair Doug Kurtis Tony Sandoval John Tuttle Pete Pfitzinger 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Miki Gorman Patti Lyons Dillon Bob Kempainen Helen Klein Keith Brantly Greg Meyer Herb Lindsay Cathy O’Brien Lisa Rainsberger Steve Spence 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Deena Kastor Jenny Spangler Beth Bonner Anne Marie Letko Libbie Hickman Meb Keflezighi Judi St. -

MPRR Summer(8-1/2X11)

The Mid-Pacific Road Runner 40th ANNIVERSARY EDITION Post Office Box 2571 • Honolulu, Hawaii 96803 • www.mprrc.com • Vol III, Number 25 • Summer 2002 SUMMER 2002 The President’s Forum Club Members Pursue Spring, Summer Success, Gearing up now for Marathon Season By Bill Beauchamp This year’s run was dedicated MPRRC President to Jack Wyatt, running and water sports writer for the It’s a pleasure to report Star-Bulletin, tragically killed that our year so far has been in mid-June. Tightened securi- going great. Our spring ty at Hickam Air Force Base meeting at the Hale Koa was caused the relocation of the a resounding success with an event, and we are considering a inspiring talk by member Ed new site for the race next year. Cadman, dean of the UH With 500-plus entries for Medical School. We had the first race in the readiness more than 100 members and series, the popularity of the guests in attendance. series seems to be continuing Our running program is into the fifth year. We judge going great guns with strong from an early count of series participation in our signature applications that we’ll have a Oahu Perimeter, Johnny number of participants com- Faerber and Norman parable to last year. Tamanaha runs. The new This year is our 40th sprint series earlier in the anniversary as a club. We’re 11 Bill Beauchamp, club president, year was very well received, gestures exuberance at the finish years older than the Honolulu of the Norman Tamanaha 15K in April. and Clint Iizuka-Sheeley, who Marathon, so it looks like directed the series, promises we’re here to stay! The social committee also has set up even better next year. -

Norcal Running Review, After Such an Effort

Sep,/Oct 1979 (#78) N O R - C A L RUNNING REVIEW 1238 WOLFE ROAD 245-1381 EL CAMINO-WOLFE CENTER SUNNYVALE, CALIF. 94086 Trac shacsh o e s f o r a l l f e a t s OPEN IN SUNNYVALE 10-6 Weekdays; 'til 9 Thursdays & 10-5 Saturdays ADIDAS • BROOKS • CONVERSE • EATON • MITRE • NIKE • N E W BALANCE • PONY • PUMA • SAUCONY • TIGER Stop in and see our selection of GORE-TEX and ALL-WEATHER suits. We also have the Casio F-200, E.R.G., lots of top shoes and plenty of gift ideas (including gift certificates). SEE YOU AT THE RACES!! Athletic DeparmentWEAthletic M E E T E V E R Y R U N N I N G N E E D : ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT) O N S A L E WHILE THEY LAST -- Dolfin Singlets; Champion Singlets; SAI Women's Singlets and Shorts... REDUCED PRICES — Nike Lady Waffle Trainers EXPECTED SOON — A large shipment of Nike "Tailwinds" 2114 Addison St., Berkeley Hours: Mon-Fri. 10-6; Sat. 10-5 ( 8 4 3 - 7 7 6 7 ) Piedmont Music Foundation p r e s e n t s \ • SECOND ANNUAL PIEDMONT 5 & 10 K F O O T R A C E Saturday, October 3 | M 9 7 9 9 a.m. listration before O c t A D U L T S $ 4 F A M I L Y $ 8 3 o r m o r e A D U L T S 5 5 D i v i s i o n s o s t o n In consideration of your accepting m y entry, I, intending to be legally bound, hereby for myself, m y heirs, executors and administrators, waive and release any and all rights and claims against the persons and organizations affiliated with the race while participating in or traveling to the Piedmont Music Foundation Foot Race, October 27, 1979.1 fur ther attest that I a m physically fit and have sufficiently trained for this event. -

Honolulu Marathon Expo 2019

EXHIBITOR MANUAL ORDER FORMS FOR: Honolulu Marathon Expo 2019 @ Hawaii Convention Center December 5-7, 2019 Dear HONOLULU MARATHON EXPO 2019 Exhibitors, It is a great pleasure to have been selected as your Official Service Contractor. We will make every effort to make this a successful event for you. Attached are the Exhibitors Service Order Forms for additional services you may require for your booth. Please review, complete and submit your order forms as early as possible to take advantage of our discount pricing. We welcome you to use our safe and secure online ordering website to place your order. Please log in using your email address and temporary password provided via a separate email for all of you first time users. If you do not receive your password or have forgotten it, please call or email us for assistance. Please don’t hesitate to contact us with any concerns regarding services for your booth. You may reach us via the following: Main Office #808-832-2430 Main Fax #808-832-2431 Email: [email protected] We look forward to serving you. Sincerely, CoC Hawaii BBB Hawaii I.C.S. Management 1004 Makepono Street, Building A • Honolulu, Hawaii 96819 • Tel (808) 832-2430 • Fax (808) 832-2431 • www.IcsHawaii.net Honolulu Marathon Expo 2019 HAWAII CONVENTION CENTER DECEMBER 5-7, 2019 Cover Page Welcome Letter General Information Show Information 4 Trade Show Tips 6 Payment & Calculation Form 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Payment Terms & Conditions 8 Safety First 9 Fire & Safety Regulations 10 Limits of Liability & Responsibility 12 Material