Integrating Global Citizenship: a Self-Evaluation Framework For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Details of Files for This Subgroup

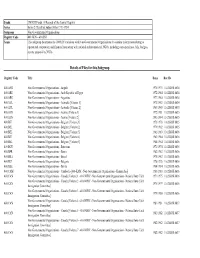

Fonds UNHCR Fonds 11 Records of the Central Registry Series Series 2 Classified Subject Files 1971-1984 Subgroup Non-Governmental Organisations Registry Code 400.GEN – 430.SSF Scope This subgroup documents the UNHCR’s relations with Non-Governmental Organisations. It contains information relating to operational cooperation and financial interaction with national and international NGOs, including correspondence, bills, budgets, reports prepared by NGOs. Details of Files for this Subgroup Registry Code Title Dates Box ID 400.ANG Non-Governmental Organisations - Angola 1975/1975 11.02.BOX.0634 400.ARE Non-Governmental Organisations - Arab Republic of Egypt 1972/1984 11.02.BOX.0634 400.ARG Non-Governmental Organisations - Argentina 1977/1984 11.02.BOX.0634 400.AUL Non-Governmental Organisations - Australia [Volume 1] 1973/1983 11.02.BOX.0634 400.AUL Non-Governmental Organisations - Australia [Volume 2] 1983/1985 11.02.BOX.0635 400.AUS Non-Governmental Organisations - Austria [Volume 1] 1972/1981 11.02.BOX.0635 400.AUS Non-Governmental Organisations - Austria [Volume 2] 1981/1984 11.02.BOX.0635 400.BEL Non-Governmental Organisations - Belgium [Volume 1] 1973/1978 11.02.BOX.0635 400.BEL Non-Governmental Organisations - Belgium [Volume 2] 1979/1982 11.02.BOX.0635 400.BEL Non-Governmental Organisations - Belgium [Volume 3] 1982/1983 11.02.BOX.0636 400.BEL Non-Governmental Organisations - Belgium [Volume 4] 1983/1984 11.02.BOX.0636 400.BEL Non-Governmental Organisations - Belgium [Volume 5] 1984/1984 11.02.BOX.0636 400.BOT Non-Governmental Organisations -

American Expatriate Writers and the Process of Cosmopolitanism a Dissert

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Beyond the Nation: American Expatriate Writers and the Process of Cosmopolitanism A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alexa Weik Committee in charge: Professor Michael Davidson, Chair Professor Frank Biess Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Don Wayne 2008 © Alexa Weik, 2008 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Alexa Weik is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii To my mother Barbara, for her everlasting love and support. iv “Life has suddenly changed. The confines of a community are no longer a single town, or even a single nation. The community has suddenly become the whole world, and world problems impinge upon the humblest of us.” – Pearl S. Buck v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………… iii Dedication………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph……………………………………………………………………. v Table of Contents…………………………………………………………… vi Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………. vii Vita………………………………………………………………………….. xi Abstract……………………………………………………………………… xii Introduction………………………………………………………………….. 1 Chapter 1: A Brief History of Cosmopolitanism…………...………………... 16 Chapter 2: Cosmopolitanism in Process……..……………… …………….... 33 -

Not for Publication United States District Court District of New Jersey : Moorish Science Temple of America 4Th & 5Th : Gene

Case 1:11-cv-07418-RBK-KMW Document 2 Filed 01/12/12 Page 1 of 12 PageID: <pageID> NOT FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY : MOORISH SCIENCE TEMPLE OF Civil Action No. 11-7418 (RBK) AMERICA 4TH & 5TH : GENERATION et al., : MEMORANDUM OPINION Plaintiff, AND ORDER : v. : SUPERIOR COURT OF NEW JERSEY at el., : Defendants. : This matter comes before the Court upon Plaintiff’s submission of a civil complaint, see Docket Entry No. 1, and an application to proceed in forma pauperis, see Docket Entry No. 1-1, and it appearing that: 1. The aforesaid complaint is executed in the style indicating that the draftor(s) was/were affected by “Moorish,” “Marrakush,” “Murakush” or akin perceptions, which often coincide with “redempotionist” and/or “sovereign citizen” socio-political beliefs. See Bey v. Stumpf, 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 120076, at *2-13 (D.N.J. Oct. 17, 2011) (detailing various aspects of said position). Moorish and Redemptionist Movements. Two concepts, which may or may not operate as interrelated, color the issues at hand. One of these concepts underlies ethnic/religious identification movement of certain groups of individuals who refer to themselves as “Moors,” while the other concept provides the basis for another movement of certain groups of individuals, which frequently produces these individuals’ denouncement of United States citizenship, self-declaration of other, imaginary Case 1:11-cv-07418-RBK-KMW Document 2 Filed 01/12/12 Page 2 of 12 PageID: <pageID> “citizenship” and accompanying self-declaration of equally imaginary “diplomatic immunity.” [a]. Moorish Movement In 1998, the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit - being one of the first courts to detail the concept of Moorish movement, observed as follows: [The Moorish Science Temple of America is a] black Islamic sect . -

World Passport from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

World Passport From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The World Passport is a document issued by the World Service Authority, a non-profit organization founded by Garry Davis in 1954,[1] citing Article 13, Section 2, of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[2] Contents 1 Appearance and issuance fees 2 As a travel document 2.1 Notable acceptances 2.2 Notable rejections 2.2.1 Commonwealth of Independent States 2.2.2 United States 2.2.3 Other countries 2.3 Use by refugees and stateless persons 3 As an identity document 4 As a political statement 5 Counterfeits and fraudulent issuance 6 List of notable World Passport holders 7 See also 8 References 9 External links Appearance and issuance fees The World Passport is similar in appearance to a national passport or other travel document. The appearance is so similar that in 1974 a criminal case was lodged against Garry Davis in France regarding his issuance of World Passports.[3] In 1979, the World Passport was a 42-page document, with a dark blue cover, and text in English, French, Spanish, Russian, Arabic, Chinese, and Esperanto. It contained a five-page section for medical history and a six-page section for listing organisational affiliation. The fee charged at that time was $32 and postage for a three-year passport with the possibility of two years' extension of validity.[4] The latest edition of the World Passport was issued January 2007. It has an embedded "ghost" photo for security, covered with a plastic film. Its data page imitates the format of a machine-readable passport, with an alphanumeric code bar in the machine- readable zone (MRZ) enabling it to be scanned by an optical reader. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Beyond the nation : American expatriate writers and the process of cosmopolitanism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2bb925ff Author Weik, Alexa Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Beyond the Nation: American Expatriate Writers and the Process of Cosmopolitanism A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alexa Weik Committee in charge: Professor Michael Davidson, Chair Professor Frank Biess Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Don Wayne 2008 © Alexa Weik, 2008 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Alexa Weik is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii To my mother Barbara, for her everlasting love and support. iv “Life has suddenly changed. The confines of a community are no longer a single town, or even a single nation. The community has suddenly become the whole world, and world problems impinge upon the humblest of us.” – Pearl S. Buck v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………… iii Dedication………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph……………………………………………………………………. -

6005894379.Pdf

The Globalization Reader The Globalization Reader Fifth Edition Edited by Frank J. Lechner and John Boli This fifth edition first published 2015 Editorial material and organization © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd Edition history: Blackwell Publishers Ltd (1e, 2000), Blackwell Publishing Ltd (2e, 2004 and 3e, 2008), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (4e, 2012) Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Frank J. Lechner and John Boli to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

Mss 006 Ferry

RUTH LILLY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES Carol Bernstein Ferry and W. H. Ferry Papers, 1971-1997 Mss 006 Carol Bernstein Ferry and W.H. Ferry Papers, 1971-1997 Mss 006 22.4 c.f. (22 cartons and 1 document box) ABSTRACT Carol Bernstein Ferry and the late W. H. (Ping) Ferry were social change philanthropists who gave away a substantial part of their personal wealth to progressive social change groups, activities, and activists concentrating generally in the areas of war, racism, poverty, and injustice. The Ferrys were also board members of the DJB Foundation, established by Carol’s first husband, Daniel J. Bernstein, which focused its giving in similar areas. The papers, 1971-1996, document the individuals, organizations, and activities the Ferrys supported with their donations. ACCESS This collection is open to the public without restriction. The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. PREFERRED CITATION Cite as: Carol Bernstein Ferry and W. H. Ferry Papers, 1971-1997, Ruth Lilly Special Collections and Archives, University Library, Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis ACQUISITION Presented by Carol Bernstein Ferry and W. H. Ferry, December 1993. A93-89, A96-33 Processed by Brenda L. Burk and Danielle Macsay, February, 1998. Ferry Finding Aid - page 2 HISTORY Carol Bernstein Ferry was born Carol Underwood in 1924 in upstate New York and grew up in Portland, Maine. She attended a private girls’ school and graduated from Wells College, a small woman’s college near Auburn, New York, in 1945. She moved to New York City in 1946 and worked as a copy editor and proofreader, eventually freelancing in that capacity for McGraw- Hill. -

United Nations Juridical Yearbook, 1993

Extract from: UNITED NATIONS JURIDICAL YEARBOOK 1993 Part Two. Legal activities of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations Chapter VI. Selected legal opinions of the Secretariats of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations Copyright (c) United Nations CONTENTS (continued) Page the non-renewal of appointment the Director-General must observe the general principles that govern the in- ternational civil service and safeguard the independence of the Organization and its officials—Question whether the complainant was on secondment—A staff member should not be made to suffer for the Organization's fail- ure to follow its own rules 327 9. Judgement No. 1250 (10 February 1993): Peña-Montenegro v. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Dismissal because of staff member's refusal to transfer- Regulation 301.012 of the Staff Regulations—Question of a staff member's family circumstances upon consid- eration of transfer—Refusal to transfer amounted to mis- conduct—Principle of proportionality in disciplinary mea- sure taken 328 10. Judgement No. 1278 (14 July 1993): Rogatko v. World Health Organization Non-renewal of fixed-term contract—Question of a substan- tive promise by an international organization and its en- forcement (Judgement No. 782 (in re Gieser)) 329 C. DECISIONS OF THE WORLD BANK ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNAL Decision No. 131 (10 December 1993): John Láveme King III v. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development Rescission of disciplinary measures—Rule 8.01 of the Staff Rules- Basic principles of due process in disciplinary matters—Ques- tion of proof of misconduct 330 CHAPTER VI. SELECTED LEGAL OPINIONS OF THE SECRETARIES OF THE UNITED NATIONS AND RELATED INTERGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS A. -

OMORUYI-THESIS.Pdf (1.375Mb)

TAKING SUFFERING SERIOUSLY: A ROBUST APPROACH TO ENFORCING THE RIGHT TO NATIONALITY OF STATELESS PEOPLE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Laws In the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Benjamin Aiwehia Omoruyi © Copyright Benjamin Omoruyi, December 2013. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Laws degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of the University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Dean of the College of Law. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean of the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5A6 Canada i ABSTRACT This thesis interrogates the continued statelessness of more than 12 million stateless people around the world, in the face of Article 15 of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which provides that everyone has a right to a nationality. -

Thanks for Coming: Four Archival Collections and the Counterculture

Thanks for coming: four archival collections and the counterculture Article (Published Version) Field, Douglas, Scott, Alison, Smith, Jessica, Wragg, Richard and Wilkinson, Bruce (2020) Thanks for coming: four archival collections and the counterculture. Counterculture Studies, 3 (1). pp. 1-28. ISSN 2209-8003 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/91537/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Thanks for Coming: Four Archival Collections and the Counterculture Introduction Douglas Field, Senior Lecturer in Twentieth Century American Literature, University of Manchester, UK. -

Luis Kutner Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0g502372 No online items Inventory of the Luis Kutner papers Finding aid prepared by Aparna Mukherjee and David Jacobs Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2007, revised 2013 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Luis Kutner 82015 1 papers Title: Luis Kutner papers Date (inclusive): 1880-1993 Collection Number: 82015 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 304 manuscript boxes, 5 oversize boxes, 1 phonotape reel(128.8 Linear Feet) Abstract: Includes writings, correspondence, legal briefs, and printed matter relating to international civil rights cases, world federation, and attempts to secure international recognition of habeas corpus and due process of law by an American lawyer who was both chairman of the Commission for International Due Process of Law and the World Habeas Corpus Commission. Sound use copy of sound recording available. Creator: Kutner, Luis, 1908-1993 Creator: Commission for International Due Process of Law Creator: World Habeas Corpus Commission Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information The Kutner papers were acquired in 1982. Incremental materials in boxes 116 to 240 were added from 1983 to 1993. Incremental materials in boxes 241 to 309 were added in 2011. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Luis Kutner papers, [Box no., Folder no. -

MATTER of DAVIS in Exclusion Proceedings A-7449011

Interim Decision #2650 MATTER OF DAVIS In Exclusion Proceedings A-7449011 Decided by Board May 24, 1978 (1) In cases involving loss of American citizenship, the law and the facts are to be construed as far as reasonably possible in favor of the claimant. (2) Under the provisions of section 3t9(c) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, the burden is on the one asserting that a loss of citizenship occurred to prove that claim by a preponderance of the evidence. (3) A voluntary renunciation of nationality in accordance with section 401(f) of the Na- tionality Act of 1940 (coati= 549(a)(G), Immigration and Nationality Act), woo effective to accomplish expatriation even if the former citizen did not acquire another nationality, and became stateless. (4) An Oath of Renunciation pursuant to section 401(f) of the Nationality Act of 1940 accomplished expatriation where the 2e was a specific intent tv renuuuce all allegiance to the United States and to become a "world" citizen. (5) Since the United States is not a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, U.N. Dec. A/CONF. 9/15 (August 29, 1961), its provisions have no applicability to loss of United States citizenship. Even if this were not the case, the Convention provides for voluntary renunciation of citizenship with resulting statelessness "where the national _ . gives definite evidence of his determination to repudiate his allegiance." (6) One who has lost United States citizenship by a voluntary oath of renunciation is no longer a national of the United States since a renunciation of citizenship embraces a renunciation of American nationality- as well.