Messe Des Morts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EARLY MUSIC NOW with SARA SCHNEIDER Broadcast Schedule — Winter 2019

EARLY MUSIC NOW WITH SARA SCHNEIDER Broadcast Schedule — Winter 2019 PROGRAM #: EMN 18-27 RELEASE: December 24, 2018 Gaudete! Music for Christmas This week's program features Christmas music from several centuries to help get you in the holiday spirit, with hymns and carols by Michael Praetorius and Johannes Brassart, a Christmas concerto by Francesco Manfredini, and a traditional German carol sung by Emma Kirkby. Other performers include La Morra and the Gabrieli Consort and Players. PROGRAM #: EMN 18-28 RELEASE: December 31, 2018 To Drive the Cold Winter Away This week, Early Music Now presents songs to usher out the old year, and welcome the new; plus ditties and dances to bring some cheer to the cold winter days! Our performers include Pomerium, Ensemble Gilles Binchois, and The Dufay Collective. PROGRAM #: EMN 18-29 RELEASE: January 7, 2019 La Serenissima The 16th century Venetian School influenced composers all over Europe- from the polychoral masterpieces of Gabrieli to the innovative keyboard music of Merulo. We'll also hear selections from the Odhecaton: the earliest music collection printed using movable type, published by Petrucci in Venice in 1501. PROGRAM #: EMN 18-30 RELEASE: January 14, 2019 Music at the court of Emperor Maximilian I Maximilian I of Austria employed some of the finest artists and musicians of his time to glorify his reign and create a permanent legacy. He was known for wanting music in his environment constantly, even when he was alone. We'll hear from the composers who served him, like Isaac and Senfl, plus some of the music that shaped his young adulthood at the Burgundian court. -

French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed As a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G. Cale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Cale, John G., "French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2112. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2112 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72-17,750 CALE, John G., 1922- FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College;, Ph.D., 1971 Music I University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by John G. Cale B.M., Louisiana State University, 1943 M.A., University of Michigan, 1949 December, 1971 PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. -

Johann Sebastian Bach Du Treuer Gott Leipzig Cantatas BWV 101 - 115 - 103

Johann Sebastian Bach Du treuer Gott Leipzig Cantatas BWV 101 - 115 - 103 Collegium Vocale Gent Philippe Herreweghe Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Nimm von uns, Herr, du treuer Gott, BWV 101 Mache dich, mein Geist, bereit, BWV 115 Ihr werdet weinen und heulen, BWV 103 Dorothee Mields Soprano Damien Guillon Alto Thomas Hobbs Tenor Peter Kooij Bass Collegium Vocale Gent Philippe Herreweghe Menu Tracklist ------------------------------ English Biographies Français Biographies Deutsch Biografien Nederlands Biografieën ------------------------------ Sung texts Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Nimm von uns, Herr, du treuer Gott, BWV 101 [1] 1. Coro: Nimm von uns, Herr, du treuer Gott ______________________________________________________________7’44 [2] 2. Aria (tenor): Handle nicht nach deinen Rechten ________________________________________________________3’30 [3] 3. Recitativo e choral (soprano): Ach! Herr Gott, durch die Treue dein__________________________________2’13 [4] 4. Aria (bass): Warum willst du so zornig sein? ___________________________________________________________ 4’14 [5] 5. Recitativo e choral (tenor): Die Sünd hat uns verderbet sehr _________________________________________ 2’11 [6] 6. Aria (soprano, alto): Gedenk an Jesu bittern Tod _______________________________________________________5’59 [7] 7. Choral: Leit uns mit deiner rechten Hand _______________________________________________________________0’55 Mache dich, mein Geist, bereit, BWV 115 [8] 1. Coro: Mache dich, mein Geist, bereit ____________________________________________________________________4’00 -

Dec 21 to 27.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Dec. 21 - 27, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 12/21/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto, Op. 3, No. 10 6:12 AM TRADITIONAL Gabriel's Message (Basque carol) 6:17 AM Francisco Javier Moreno Symphony 6:29 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Sonata No.4 6:42 AM Johann Christian Bach Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Cello 7:02 AM Various In dulci jubilo/Wexford Carol/N'ia gaire 7:12 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata No. 7 7:30 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for Trumpet and Violin 7:43 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Concerto 8:02 AM Henri Dumont Magnificat 8:15 AM Johann ChristophFriedrich Bach Oboe Sonata 8:33 AM Franz Krommer Concerto for 2 Clarinets 9:05 AM Joaquin Turina Sinfonia Sevillana 9:27 AM Philippe Gaubert Three Watercolors for Flute, Cello and 9:44 AM Ralph Vaughan Williams Fantasia on Christmas Carols 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Prelude & Fugue after Bach in d, 10:07 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata No. 9 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 29 10:50 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Prelude (Fantasy) and Fugue 11:01 AM Mily Balakirev Symphony No. 2 11:39 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Overture (suite) for 3 oboes, bsn, 2vns, 12:00 PM THE CHRISTMAS REVELS: IN CELEBRATION OF THE WINTER SOLSTICE 1:00 PM Richard Strauss Oboe Concerto 1:26 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 2:00 PM James Pierpont Jingle Bells 2:07 PM Julius Chajes Piano Trio 2:28 PM Francois Devienne Symphonie Concertante for flute, 2:50 PM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto, "Il Riposo--Per Il Natale" 3:03 PM Zdenek Fibich Symphony No. -

Direction 2. Ile Fantaisies

CD I Josquin DESPREZ 1. Nymphes des bois Josquin Desprez 4’46 Vox Luminis Lionel Meunier: direction 2. Ile Fantaisies Josquin Desprez 2’49 Ensemble Leones Baptiste Romain: fiddle Elisabeth Rumsey: viola d’arco Uri Smilansky: viola d’arco Marc Lewon: direction 3. Illibata dei Virgo a 5 Josquin Desprez 8’48 Cappella Pratensis Rebecca Stewart: direction 4. Allégez moy a 6 Josquin Desprez 1’07 5. Faulte d’argent a 5 Josquin Desprez 2’06 Ensemble Clément Janequin Dominique Visse: direction 6. La Spagna Josquin Desprez 2’50 Syntagma Amici Elsa Frank & Jérémie Papasergio: shawms Simen Van Mechelen: trombone Patrick Denecker & Bernhard Stilz: crumhorns 7. El Grillo Josquin Desprez 1’36 Ensemble Clément Janequin Dominique Visse: direction Missa Lesse faire a mi: Josquin Desprez 8. Sanctus 7’22 9. Agnus Dei 4’39 Cappella Pratensis Rebecca Stewart: direction 10. Mille regretz Josquin Desprez 2’03 Vox Luminis Lionel Meunier: direction 11. Mille regretz Luys de Narvaez 2’20 Rolf Lislevand: vihuela 2: © CHRISTOPHORUS, CHR 77348 5 & 7: © HARMONIA MUNDI, HMC 901279 102 ITALY: Secular music (from the Frottole to the Madrigal) 12. Giù per la mala via (Lauda) Anonymous 6’53 EnsembleDaedalus Roberto Festa: direction 13. Spero haver felice (Frottola) Anonymous 2’24 Giovanne tutte siano (Frottola) Vincent Bouchot: baritone Frédéric Martin: lira da braccio 14. Fammi una gratia amore Heinrich Isaac 4’36 15. Donna di dentro Heinrich Isaac 1’49 16. Quis dabit capiti meo aquam? Heinrich Isaac 5’06 Capilla Flamenca Dirk Snellings: direction 17. Cor mio volunturioso (Strambotto) Anonymous 4’50 Ensemble Daedalus Roberto Festa: direction 18. -

Psalms to Plainchant: Seventeenth-Century Sacred Music in New England and New France

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1989 Psalms to Plainchant: Seventeenth-Century Sacred Music in New England and New France Caroline Beth Kunkel College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Recommended Citation Kunkel, Caroline Beth, "Psalms to Plainchant: Seventeenth-Century Sacred Music in New England and New France" (1989). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625537. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-874z-r767 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PSALMS TO PLAINCHANT Seventeenth-Century Sacred Music in New England and New France A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Caroline B. Kunkel 1989 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Caroline B. Kunkel Approved, May 1990 < 3 /(yCeJU______________ James Axtell A )ds Dale Cockrell Department of Music (IlliM .d (jdb&r Michael McGiffertA / I All the various affections of our soul have modes of their own in music and song by which they are stirred up as by an indescribable and secret sympathy. - St. Augustine Sermo To my parents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS........ -

The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music After the Revolution

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2013-8 The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Connolly, D. (2013) The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution. Doctoral Thesis. Dublin, Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D76S34 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly, BA, MA, HDip.Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama Supervisor: Dr David Mooney Conservatory of Music and Drama August 2013 i I certify that this thesis which I now submit for examination for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in Music, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. This thesis was prepared according to the regulations for postgraduate study by research of the Dublin Institute of Technology and has not been submitted in whole or in part for another award in any other third level institution. -

2-11 Juin 2011

e Cathédrale XXVIII de Maguelone 2 -11 JUIN 2011 musiqueancienneamaguelone.com Le XXVIIIe Festival de Musique à Maguelone est organisé par l’Association “Les Amis du Festival de Maguelone” Direction du Festival : Philippe Leclant avec le concours du Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication du Département de l’Hérault des Villes de Palavas-les-Flots et de Villeneuve-les-Maguelone du Réseau Européen de Musique Ancienne (REMA) en collaboration avec l'Association des Compagnons de Maguelone en partenariat avec e-mecenes.com partenaires média Un regard sur les saisons passées English Concert Ensemble 415 Hespèrion XXI Eric Bellocq Chichester Cathedral Choir Paul O’Dette Ensemble Concordia Ensemble William Byrd La Grande Ecurie Alla Francesca Françoise Masset Stéphanie-Marie Degand et la Chambre du Roy Gérard Lesne Ensemble XVIII-21 Violaine Cochard Concerto Rococo Daedalus Hélène Schimtt Ensemble Amarillis Chœurs Orthodoxes Pascal Montheilhet Dialogos Amandine Beyer du Monastère de Zagorsk Jérome Hantaï Céline Frisch Chœur du Patriarcat Russe Olivier Baumont Marianne Muller Jordi Savall The Tallis Scholars La Simphonie du Marais Les Paladins L’Arpeggiata Musica Antiqua de Cologne Ensemble Huelgas Ensemble Faenza Blandine Rannou Chœurs Liturgiques La Colombina Guido Balestracci Ensemble Marin Mersenne Arméniens d’Erevan Pierre Hantaï Neapolis Ensemble Les Sacqueboutiers de Toulouse Ensemble Organum Les Talens Lyriques Ensemble Jachet de Mantoue Paolo Pandolfo La Fenice Patrizia Bovi, Gigi Casabianca Fretwork Quatuor Madrigalesca A Sei -

Le Temple De La Gloire

april insert 4.qxp_Layout 1 5/10/17 7:08 AM Page 15 A co-production of Cal Performances, Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale, and Centre de musique baroque de Versailles Friday and Saturday, April 28 –29, 2017, 8pm Sunday, April 30, 2017, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Jean-Philippe Rameau Le Temple de la Gloire (The Temple of Glory) Opera in three acts with a prologue Libretto by Voltaire featuring Nicholas McGegan, conductor Marc Labonnette Camille Ortiz-Lafont Philippe-Nicolas Martin Gabrielle Philiponet Chantal Santon-Jeffery Artavazd Sargsyan Aaron Sheehan New York Baroque Dance Company Catherine Turocy, artistic director Brynt Beitman Caroline Copeland Carly Fox Horton Olsi Gjeci Alexis Silver Meggi Sweeney Smith Matthew Ting Andrew Trego Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale Bruce Lamott, chorale director Catherine Turocy, stage director and choreographer Scott Blake, set designer Marie Anne Chiment, costume designer Pierre Dupouey, lighting designer Sarah Edgar, assistant director Cath Brittan, production director Major support for Le Temple de la Gloire is generously provided by Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale supporters: David Low & Dominique Lahaussois, The Waverley Fund, Mark Perry & Melanie Peña, PBO’s Board of Directors, and The Bernard Osher Foundation. Cal Performances and Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale dedicate Le Temple de la Gloire to Ross E. Armstrong for his extraordinary leadership in both our organizations, his friendship, and his great passion for music. This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Susan Graham Harrison and Michael A. Harrison, and Francoise Stone. Additional support made possible, in part, by Corporate Sponsor U.S. Bank. april insert 4.qxp_Layout 1 5/10/17 7:08 AM Page 16 Title page of the original 1745 libretto of Le Temple de la Gloire . -

Judith Van Wanroij • Robert Getchell Juan Sancho • Lisandro Abadie Capriccio Stravagante Les 24 Violons Collegium Vocale G

RAMEAU’S FUNERAL Paris 27. IX. 1764 Jean Gilles • Messe des Morts Judith van Wanroij • Robert Getchell Juan Sancho • Lisandro Abadie Capriccio Stravagante Les 24 Violons Collegium Vocale Gent Skip Sempé RAMEAU’S FUNERAL 4 Graduel I 3’37 Le Service Funèbre de Rameau 5 Graduel II 5’06 Robert Getchell, haute-contre Paris 27. IX. 1764 6 Offertoire 8’29 Judith van Wanroij, dessus 7 Sanctus 1’59 Robert Getchell, haute-contre 8 Hommage à Rameau Juan Sancho, taille Tristes apprêts (Castor et Pollux) 3’18 Lisandro Abadie, basse Jasu Moisio, hautbois Capriccio Stravagante Les 24 Violons 9 Elévation 8’22 Collegium Vocale Gent Judith van Wanroij, dessus Skip Sempé 10 Benedictus 1’59 11 Agnus Dei 3’53 12 Communion 4’06 Jean Gilles (1668-1705) Messe des Morts 13 Sommeil éternel de Rameau (Paris version, 27. IX. 1764) Rondeau tendre (Dardanus) 2’55 14 Apothéose de Rameau Hommages à Rameau (1683-1764) Air des esprits infernaux (Zoroastre) 2’30 1 Introit 11’38 2 Kyrie 4’05 Total time 63’35 3 Hommage à Rameau Gravement (Dardanus) 1’37 2 3 Capriccio Stravagante Les 24 Violons Collegium Vocale Gent Dessus de violon Sophie Gent, Jacek Kurzydło, Maite Larburu, Louis Créac’h Dessus David Wish, Yannis Roger, Marie Rouquié Griet De Geyter, Katja Kunze Haute-contre de violon Aleksandra Lewandowska, Dominique Verkinderen Tuomo Suni, Joanna Huszcza Gabriel Grosbard, Aira Maria Lehtipuu, Myriam Mahnane Taille de violon Haute-contre Simon Heyerick, Martha Moore Sofia Gvirts, Cécile Pilorger Quinte de violon Alexander Schneider, Bart Uvyn David Glidden, Samantha Montgomery -

The Aquitanian Sacred Repertoire in Its Cultural Context

THE AQUITANIAN SACRED REPERTOIRE IN ITS CULTURAL CONTEXT: AN EXAMINATION OF PETRI CLA VIGER! KARl, IN HOC ANNI CIRCULO, AND CANTUMIRO SUMMA LAUDE by ANDREA ROSE RECEK A THESIS Presented to the School ofMusic and Dance and the Graduate School ofthe University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2008 11 "The Aquitanian Sacred Repertoire in Its Cultural Context: An Examination ofPetri clavigeri kari, In hoc anni circulo, and Cantu miro summa laude," a thesis prepared by Andrea Rose Recek in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master ofArts degree in the School ofMusic and Dance. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Dr. Lori Kruckenberg, Chair ofth xamining Committee Committee in Charge: Dr. Lori Kruckenberg, Chair Dr. Marc Vanscheeuwijck Dr. Marian Smith Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School 111 © 2008 Andrea Rose Recek IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Andrea Rose Recek for the degree of Master ofArts in the School ofMusic and Dance to be taken September 2008 Title: THE AQUITANIAN SACRED REPERTOIRE IN ITS CULTURAL CONTEXT: AN EXAMINATION OF PETRI CLA VIGER! KARl, INHOC ANNI CIRCULO, AND CANTU MIRa SUMMA LAUDE Approved: ~~ _ Lori Kruckenberg Medieval Aquitaine was a vibrant region in terms of its politics, religion, and culture, and these interrelated aspects oflife created a fertile environment for musical production. A rich manuscript tradition has facilitated numerous studies ofAquitanian sacred music, but to date most previous research has focused on one particular facet of the repertoire, often in isolation from its cultural context. This study seeks to view Aquitanian musical culture through several intersecting sacred and secular concerns and to relate the various musical traditions to the region's broader societal forces. -

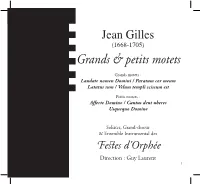

Grands & Petits Motets

Jean Gilles (1668-1705) Grands & petits motets Grands motets : Laudate nomen Domini / Paratum cor meum Lætatus sum / Velum templi scissum est Petits motets : Afferte Domino / Cantus dent uberes Usquequo Domine Solistes, Grand-chœur & Ensemble Instrumental des ees d’Orphée Direction : Guy Laurent 1 Grands & petits motets Grand motet Laudate nomen Domini 19’53 1 Prélude / Récit de Taille / Chœur, avec Duos et Trios 4’26 2 Prélude / Récits de Basse et de Haute-Contre / Chœur 2’42 3 Récit de Haute-Contre 2’12 4 Prélude / Chœur, avec Trio 3’01 5 Récit de Taille 1’33 6 Prélude / Récit de Baryton / Duo de Baryton et Basse 2’19 7 Prélude / Récit de Taille / Chœur, avec Récits de Taille et Trios 3’37 Petit motet Afferte Domino 4’12 8 Afferte Domino 2’36 9 Lætentur cæli 1’36 Grand motet Paratum cor meum 10’35 10 Prélude / Récit de Baryton / Duo de Dessus et Baryton 2’58 11 Prélude / Récits de Haute-Contre, Chœur et Dessus 2’58 12 Trio de Dessus, Baryton et Basse 1’42 13 Récit de Taille / Chœur 2’57 2 Petit motet Cantus dent uberes 6’00 14 Cantus dent uberes 2’03 15 Sub panis 2’05 16 Verus Deus 1’52 Grand motet Lætatus sum 9’36 17 Récit de Haute-Contre 1’39 18 Chœur, avec Duo et Trio 1’05 19 Récit de Baryton / Duo de Haute-Contre et Baryton 2’13 20 Prélude / Récit de Taille 1’37 21 Chœur, avec Trio 1’27 22 Récit de Basse / Chœur avec Trios 1’35 Petit motet Usquequo Domine 5’19 23 Prélude / Récit de Baryton / Duo de Dessus et Baryton 2’19 24 Prélude / Récits de Haute-Contre, Chœur et Dessus 0’52 25 Trio de Dessus, Baryton et Basse 2’08 Grand motet