Hope, Pain & Patience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Informal Peace Efforts

CMI BRIEF 2018:7 1 NUMBER 7 CMI BRIEF NOVEMBER 2018 Photo courtesy of Isis-WICCE Women’s informal peace efforts: Grassroots activism in South Sudan AUTHORS South Sudanese women have been grossly under-represented Helen Kezie-Nwoha in formal peace negotiations. However, they have been active Juliet Were in informal peacebuilding at the local level where peace means rebuilding society. Such informal peacebuilding is radically different to formal peace negotiations where male warlords and political leaders in new positions of power divide the spoils of war. This brief describes women’s informal peace work in South Sudan, and shows the extensive and valuable, but often unrecognized work that women’s organizations do. We also look at how women’s roles in formal processes are informed by women’s informal work. 2 CMI BRIEF 2018:7 Methodology In this study, we conducted individual and focus groups discussions with women activists from groups located in South Sudan and in Uganda. We completed 21 individual interviews, eight focus group discussions (with a total of 111 women) and two community meetings with 90 women in all. The interviews were conducted between June 2017 and July 2018. Fighting between different warring factions caused delays and made it difficult to access study locations. The long road to peace Women’s role in formal peace processes South Sudan gained independence from Sudan on 9 July 2011. Since then, South Sudan has been marred by internal conflicts. What started as a power struggle Women’s under-representation in peace between President Salva Kiir and his deputy, former negotiations is the norm rather than Vice President Riek Machar, quickly devolved into a war the exception. -

Childbirth in South Sudan: Preferences, Practice and Perceptions in the Kapoetas Heather M

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Childbirth in South Sudan: Preferences, practice and perceptions in the Kapoetas Heather M. Buesselera and James Yugib a American Refugee Committee International, Minneapolis, USA b American Refugee Committee International, Juba, South Sudan Correspondence to: Heather Buesseler [email protected] BACKGROUND: Focus group discussions (FGDs) were designed to better understand the community’s views and preferences around maternity care to design a communications campaign to increase facility deliveries and skilled attendance at birth in the three county catchment areas of Kapoeta Civil Hospital. METHODS: Twelve FGDs were conducted in Kapoeta South, Kapoeta East, and Kapoeta North counties. Four South Sudanese facilitators (two women, two men) were hired and trained to conduct sex-segregated FGDs. Each had 8-10 participants. Participants were adult women of reproductive age (18-49 years) and adult men (18+ years) married to women of reproductive age. RESULTS: The majority of participants’ most recent births took place at home, though most reportedly intended to give birth in a health facility and overwhelmingly desire a facility birth next time. Husbands and the couple’s mothers are the primary decision-makers about where a woman delivers. More men than women preferred home births, and they tend to have more negative opinions than women about health facility deliveries. Though participants acknowledge that health facilities can theoretically provide better care than home births, fear of surgical interventions, lack of privacy, and perceived poor quality of care remain barriers to facility deliveries. RECOMMENDATIONS: Interventions encouraging facility births should target the decision-makers—husbands and a couple’s mothers. Improvements in quality of care are needed in health facilities. -

Past, Present, and Future FIFTY YEARS of ANTHROPOLOGY in SUDAN

Past, present, and future FIFTY YEARS OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN SUDAN Munzoul A. M. Assal Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil Past, present, and future FIFTY YEARS OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN SUDAN Munzoul A. M. Assal Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil FIFTY YEARS OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN SUDAN: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE Copyright © Chr. Michelsen Institute 2015. P.O. Box 6033 N-5892 Bergen Norway [email protected] Printed at Kai Hansen Trykkeri Kristiansand AS, Norway Cover photo: Liv Tønnessen Layout and design: Geir Årdal ISBN 978-82-8062-521-2 Contents Table of contents .............................................................................iii Notes on contributors ....................................................................vii Acknowledgements ...................................................................... xiii Preface ............................................................................................xv Chapter 1: Introduction Munzoul A. M. Assal and Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil ......................... 1 Chapter 2: The state of anthropology in the Sudan Abdel Ghaffar M. Ahmed .................................................................21 Chapter 3: Rethinking ethnicity: from Darfur to China and back—small events, big contexts Gunnar Haaland ........................................................................... 37 Chapter 4: Strategic movement: a key theme in Sudan anthropology Wendy James ................................................................................ 55 Chapter 5: Urbanisation and social change in the Sudan Fahima Zahir El-Sadaty ................................................................ -

South Sudan Country Portfolio

South Sudan Country Portfolio Overview: Country program established in 2013. USADF currently U.S. African Development Foundation Partner Organization: Foundation for manages a portfolio of 9 projects and one Cooperative Agreement. Tom Coogan, Regional Director Youth Initiative Total active commitment is $737,000. Regional Director Albino Gaw Dar, Director Country Strategy: The program focuses on food security and Email: [email protected] Tel: +211 955 413 090 export-oriented products. Email: [email protected] Grantee Duration Value Summary Kanybek General Trading and 2015-2018 $98,772 Sector: Agro-Processing (Maize Milling) Investment Company Ltd. Location: Mugali, Eastern Equatoria State 4155-SSD Summary: The project funds will be used to build Kanybek’s capacity in business and financial management. The funds will also build technical capacity by providing training in sustainable agriculture and establishing a small milling facility to process raw maize into maize flour. Kajo Keji Lulu Works 2015-2018 $99,068 Sector: Manufacturing (Shea Butter) Multipurpose Cooperative Location: Kajo Keji County, Central Equatoria State Society (LWMCS) Summary: The project funds will be used to develop LWMCS’s capacity in financial and 4162-SSD business management, and to improve its production capacity by establishing a shea nut purchase fund and purchasing an oil expeller and related equipment to produce grade A shea butter for export. Amimbaru Paste Processing 2015-2018 $97,523 Sector: Agro-Processing (Peanut Paste) Cooperative Society (APP) Location: Loa in the Pageri Administrative Area, Eastern Equatoria State 4227-SSD Summary: The project funds will be used to improve the business and financial management of APP through a series of trainings and the hiring of a management team. -

The Characteristics of Trauma

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Music and Trauma in the Contemporary South African Novel“ Verfasser Christian Stiftinger angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2011. Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 344 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: UF Englisch Betreuer: Univ. Prof. DDr . Ewald Mengel Declaration of Authenticity I hereby confirm that I have conceived and written this thesis without any outside help, all by myself in English. Any quotations, borrowed ideas or paraphrased passages have been clearly indicated within this work and acknowledged in the bibliographical references. There are no hand-written corrections from myself or others, the mark I received for it can not be deducted in any way through this paper. Vienna, November 2011 Christian Stiftinger Table of Contents 1. Introduction......................................................................................1 2. Trauma..............................................................................................3 2.1 The Characteristics of Trauma..............................................................3 2.1.1 Definition of Trauma I.................................................................3 2.1.2 Traumatic Event and Subjectivity................................................4 2.1.3 Definition of Trauma II................................................................5 2.1.4 Trauma and Dissociation............................................................7 2.1.5 Trauma and Memory...……………………………………………..8 2.1.6 Trauma -

Rhetoric and Resistance in Black Women's Autobiography

Rhetoric and Resistance in Black Women’s Autobiography Copyright 2003 by Johnnie M. Stover. This work is licensed under a modified Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No De- rivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. You are free to electronically copy, distribute, and transmit this work if you attribute authorship. However, all printing rights are reserved by the University Press of Florida (http://www.upf.com). Please con- tact UPF for information about how to obtain copies of the work for print distribution. You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permis- sion from the University Press of Florida. Nothing in this license impairs or restricts the author’s moral rights. Florida A&M University, Tallahassee Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton Florida Gulf Coast University, Ft. Myers Florida International University, Miami Florida State University, Tallahassee New College of Florida University of Central Florida, Orlando University of Florida, Gainesville University of North Florida, Jacksonville University of South Florida, Tampa University of West Florida, Pensacola Rhetoric and Resistance in Black Women’s Autobiography ° Johnnie M. Stover University Press of Florida Gainesville/Tallahassee/Tampa/Boca Raton Pensacola/Orlando/Miami/Jacksonville/Ft. Myers Copyright 2003 by Johnnie M. -

Becoming Christian: Personhood and Moral Cosmology in Acholi South

Becoming Christian: Personhood and Moral Cosmology in Acholi South Sudan Ryan Joseph O’Byrne Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Department of Anthropology, University College London (UCL) September, 2016 1 DECLARATION I, Ryan Joseph O’Byrne, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where material has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Ryan Joseph O’Byrne, 21 September 2016 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines contemporary entanglements between two cosmo-ontological systems within one African community. The first system is the indigenous cosmology of the Acholi community of Pajok, South Sudan; the other is the world religion of evangelical Protestantism. Christianity has been in the region around 100 years, and although the current religious field represents a significant shift from earlier compositions, the continuing effects of colonial and early missionary encounters have had significant impact. This thesis seeks to understand the cosmological transformations involved in all these encounters. This thesis provides the first in-depth account of South Sudanese Acholi – a group almost entirely absent from the ethnographic record. However, its largest contributions come through wider theoretical and ethnographic insights gained in attending to local Acholi cosmological, ontological, and experiential orientations. These contributions are: firstly, the connection of Melanesian ideas of agency and personhood to Africa, demonstrating not only the relational nature of Acholi personhood but an understanding of agency acknowledging nonhuman actors; secondly, a demonstration of the primarily relational nature of local personhood whereby Acholi and evangelical persons and relations are similarly structured; and thirdly, an argument that, in South Sudan, both systems are ultimately about how people organise the moral fabric of their society. -

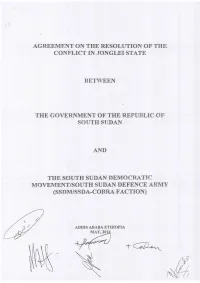

Movement/South Sudan Defence Army (§Sdm/Ssda-Cobra Faction)

AGREEMENT ON THE RESOLUTION OF THE CONFLICT iN JONGLEI STA'JfE BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTHSUDAN AND THE SOUTH SUDAN DEMOCRATIC MOVEMENT/SOUTH SUDAN DEFENCE ARMY (§SDM/SSDA-COBRA FACTION) ADDIS ABABA ETHIOPIA ~~ 1 PREAMBLE The Government of the Republic of South Sudan and the South Sudan Democratic Movement/Defense Army Cobra Faction met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia between April 30 to May 9 2014 under the auspices of the Church Leadership Mediation Initiative (CLMI) on Jonglei peace dialogue chaired by Bishop Paride Taban: DETERMINED to achieve peace and promote unity amongst the different ethnic communities in the region including the Dinka, Nuer, Murle, Anyuak, Kechipo and Jie being multicultural, multi-lingual and multi-religious; COMMITTED to abandon the culture of rev.enge including inhuman activities such as child abduction, murder, rape and torture; MINDFUL of the fact that the country is in need ofa peaceful and durable solution to the conf1ict that made the SSDM/A, Cobra Faction resort to armed option; A W ARE of the current engagement in negotiations to find solutions to the conflicts taking place in the Country generally in order to reach a comprehensive peace deal; CONSCIOUS of the need to end the problem of internal displacement amongst the population; and NOW THEREFORE, the parties agree to abide by the terms of this agreement and respect its implementation to the letter and spirit: ~ +~ ,.. Ar 2 ~1}/1J 2 GUIDING PRINCIPLES 2. ı The Republic of South Sudan is governed on the hasis ofa decentralizcd democratic system and is an all-embracing homeland for its people generally; 2. -

Women's Experiences with Abortion Complications in the Post War Context of South Sudan

Women's Experiences with Abortion Complications in the Post War Context of South Sudan Author: Monica Adhiambo Onyango Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1836 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2010 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College William F. Connell School of Nursing WOMEN’S EXPERIENCES WITH ABORTION COMPLICATIONS IN THE POST WAR CONTEXT OF SOUTH SUDAN A dissertation by MONICA ADHIAMBO ONYANGO Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 © Copyright by MONICA ADHIAMBO ONYANGO 2010 ii Women’s experiences with abortion complications in the post war context of South Sudan Monica Adhiambo Onyango Dissertation Chair: Rosanna Demarco, PhD, PHCNS-BC, ACRN, FAAN Committee Members: Sandra Mott, PhD, RNC and Pamela Grace, PhD, APRN Abstract For 21 years (1983-2004), the civil war in Sudan concentrated in the South resulting in massive population displacements and human suffering. Following the comprehensive peace agreement in 2005, the government of South Sudan is rebuilding the country’s infrastructure. However, the post war South Sudan has some of the worst health indicators, lack of basic services, poor health infrastructure and severe shortage of skilled labor. The maternal mortality ratio for example is 2,054/100,000 live births, currently the highest in the world. Abortion complication leads among causes of admission at the gynecology units. This research contributes nursing knowledge on reproductive health among populations affected by war. The purpose was to explore the experiences of women with abortion complications in the post war South Sudan. -

Annex 2 USAID South Sudan Gender Based Violence Prevention And

USAID/SOUTH SUDAN GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP SEPTEMBER 2019 Contract No.: AID-OAA-TO-17-00018 September 26, 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Banyan Global. Contract No.: AID-OAA-TO-17-00018 Submitted to: USAID/South Sudan DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. Recommended Citation: Gardsbane, Diane and Aluel Atem. USAID/South Sudan Gender-Based Violence Prevention and Response Roadmap. Prepared by Banyan Global. 2019. Cover photo credit: USAID Back Cover photo credit: USAID USAID/SOUTH SUDAN GENDER- BASED VIOLENCE PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP SEPTEMBER 2019 Contract No.: AID-OAA-TO-17-00018 4 USAID/SOUTH SUDAN GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 9 1.1 ROADMAP OBJECTIVE 9 1.2 STRUCTURE OF ROADMAP 9 2. INTEGRATING GBV IN THE USAID/SOUTH SUDAN OPERATIONAL FRAMEWORK 11 2.1 THEORY OF CHANGE 11 2.2 INTEGRATING THE THEORY OF CHANGE INTO THE USAID/SOUTH SUDAN OPERATIONAL FRAMEWORK 12 3. GBV PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP PROGRAMMATIC GUIDING PRINCIPLES 19 4. BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER – GBV PREVENTION, MITIGATION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP 27 5. GUIDELINES TO ADDRESS GBV IN MONITORING, EVALUATION AND LEARNING 39 6. KEY RESOURCES 41 ANNEX A: GBV PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP LITERATURE REVIEW 57 ANNEX B: PROGRAM AND DONOR REPORT 73 ANNEX C: GBV LITERACY TRAINING 95 ANNEX D: LIST OF KEY DOCUMENTS CONSULTED 99 ANNEX E. -

An Analysis of Pibor County, South Sudan from the Perspective of Displaced People

Researching livelihoods and services affected by conflict Livelihoods, access to services and perceptions of governance: An analysis of Pibor county, South Sudan from the perspective of displaced people Working Paper 23 Martina Santschi, Leben Moro, Philip Dau, Rachel Gordon and Daniel Maxwell September 2014 About us Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) aims to generate a stronger evidence base on how people make a living, educate their children, deal with illness and access other basic services in conflict-affected situations (CAS). Providing better access to basic services, social protection and support to livelihoods matters for the human welfare of people affected by conflict, the achievement of development targets such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and international efforts at peace- and state-building. At the centre of SLRC’s research are three core themes, developed over the course of an intensive one- year inception phase: . State legitimacy: experiences, perceptions and expectations of the state and local governance in conflict-affected situations . State capacity: building effective states that deliver services and social protection in conflict- affected situations . Livelihood trajectories and economic activity under conflict The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the lead organisation. SLRC partners include the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in Sri Lanka, Feinstein International Center (FIC, Tufts University), the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), the Sustainable Development Policy -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings ..............................................................................................................................................