Setauket Spy Ring Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spies That Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2020 Apr 27th, 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage Masaki Lew Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the History Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Lew, Masaki, "The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage" (2020). Young Historians Conference. 19. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2020/papers/19 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage Masaki Lew Humanities Western Civilization 102 March 16, 2020 1 Continental Spy Nathan Hale, standing below the gallows, spoke to his British captors with nothing less than unequivocal patriotism: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”1 American History idolizes Hale as a hero. His bravery as the first pioneer of American espionage willing to sacrifice his life for the growing colonial sentiment against a daunting global empire vindicates this. Yet, behind Hale’s success as an operative on -

The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1966 The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777 Bernard Mason State University of New York at Binghamton Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Mason, Bernard, "The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777" (1966). United States History. 66. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/66 The 'l(qpd to Independence This page intentionally left blank THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE The 'R!_,volutionary ~ovement in :J{£w rork, 1773-1777~ By BERNARD MASON University of Kentucky Press-Lexington 1966 Copyright © 1967 UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS) LEXINGTON FoR PERMISSION to quote material from the books noted below, the author is grateful to these publishers: Charles Scribner's Sons, for Father Knickerbocker Rebels by Thomas J. Wertenbaker. Copyright 1948 by Charles Scribner's Sons. The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., for John Jay by Frank Monaghan. Copyright 1935 by the Bobbs-Merrill Com pany, Inc., renewed 1962 by Frank Monaghan. The Regents of the University of Wisconsin, for The History of Political Parties in the Province of New York J 17 60- 1776) by Carl L. Becker, published by the University of Wisconsin Press. Copyright 1909 by the Regents of the University of Wisconsin. -

Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge the Following Excerpts Were Prepared by Col

Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge The following excerpts were prepared by Col. Benjamin Tallmadge THE SUBJECT OF THIS memoir was born at Brookhaven, on Long Island, in Suffolk county, State of New York, on the 25th of February, 1754. His father, the Rev. Benjamin Tallmadge, was the settle minister of that place, having married Miss Susannah Smith, the daughter of the Rev. John Smith, of White Plains, Westchester county, and State of New York, on the 16th of May, 1750. I remember my grandparents very well, having visited them often when I was young. Of their pedigree I know but little, but have heard my grandfather Tallmadge say that his father, with a brother, left England together, and came tot his country, one settling at East Hampton, on Long Island, and the other at Branford, in Connecticut. My father descended from the latter stock. My father was born at New Haven, in this State, January 1st, 1725, and graduated at Yale College, in the year 1747, and was ordained at Brookhaven, or Setauket, in the year 1753, where he remained during his life. He died at the same place on the 5th of February, 1786. My mother died April 21st, 1768, leaving the following children, viz.: William Tallmadge, born October 17, 1752, died in the British prison , 1776. Benjamin Tallmadge, born February 25, 1754, who writes this memoranda. Samuel Tallmadge, born November 23, 1755, died April 1, 1825. John Tallmadge, born September 19, 1757, died February 24, 1823. Isaac Tallmadge, born February 25, 1762. My honored father married, for his second wife, Miss Zipporah Strong, January 3rd, 1770, by whom he had no children. -

“Extracts from Some Rebel Papers”: Patriots, Loyalists, and the Perils of Wartime Printing

1 “Extracts from some Rebel Papers”: Patriots, Loyalists, and the Perils of Wartime Printing Joseph M. Adelman National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow American Antiquarian Society Presented to the Joint Seminar of the McNeil Center for Early American Studies And the Program in Early American Economy and Society, LCP Library Company of Philadelphia, 1314 Locust Street, Philadelphia 24 February 2012 3-5 p.m. *** DRAFT: Please do not cite, quote, or distribute without permission of the author. *** 2 The eight years of the Revolutionary War were difficult for the printing trade. After over a decade of growth and increasing entanglement among printers as their networks evolved from commercial lifelines to the pathways of political protest, the fissures of the war dispersed printers geographically and cut them off from their peers. Maintaining commercial success became increasingly complicated as demand for printed matter dropped, except for government printing, and supply shortages crippled communications networks and hampered printers’ ability to produce and distribute anything that came off their presses. Yet even in their diminished state, printers and their networks remained central not only to keeping open lines of communication among governments, armies, and civilians, but also in shaping public opinion about the central ideological issues of the war, the outcomes of battles, and the meaning of events affecting the war in North America and throughout the Atlantic world. What happened to printers and their networks is of vital importance for understanding the Revolution. The texts that historians rely on, from Common Sense and The Crisis to rural newspapers, almanacs, and even diaries and correspondence, were shaped by the commercial and political forces that printers navigated as they produced printed matter that defined the scope of debate and the nature of the discussion about the war. -

Here, a Single Source Is the Only Witness

The Spy Who Never Was The Strange Case of John Honeyman and Revolutionary War Espionage Alexander Rose sion so gravely threaten the John Honeyman is famed as Revolution’s survival. the secret agent who saved George Washington and the The problem is, John Honey- Continental Army during the man was no spy—or at least, dismal winter of 1776/77. At a not one of Washington’s. In this time when Washington had suf- essay I will establish that the fered an agonizing succession of key parts of the story were defeats at the hands of the Brit- The problem is, John invented or plagiarized long “ ish, it was Honeyman who after the Revolution and, Honeyman was no brought the beleaguered com- through repetition, have spy.…Key parts of his mander precise details of the become accepted truth. I exam- story were invented…and Hessian enemy’s dispositions at ine our knowledge of the tale, through repetition have Trenton, New Jersey. assess the veracity of its compo- become accepted truth. nents, and trace its DNA to the Soon afterwards, acting his single story—a piece of family part as double agent, Honey- history published nearly 100 man informed the gullible Col. years after the battle. 1 These Johann Rall, the Hessian com- historical explorations addition- ” ally will remind modern intelli- mander, that the colonials were in no shape to attack. Washing- gence officers and analysts that ton’s men, he said, were suffer- the undeclared motives of ing dreadfully from the cold and human sources may be as many were unshod. -

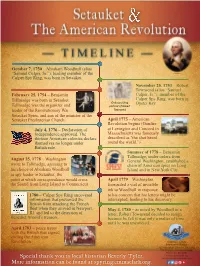

Special Thank You to Local Historian Beverly Tyler. More Information Can Be Found at Spyring.Emmaclark.Org

October 7, 1750 – Abraham Woodhull (alias “Samuel Culper, Sr.”), leading member of the Culper Spy Ring, was born in Setauket. November 25, 1753 – Robert Townsend (alias “Samuel February 25, 1754 – Benjamin Culper, Jr.”), member of the Tallmadge was born in Setauket. Culper Spy Ring, was born in Only surviving Oyster Bay. Tallmadge was the organizer and portrait of Robert leader of the Revolutionary War Townsend Setauket Spies, and son of the minister of the Setauket Presbyterian Church. April 1775 – American Revolution begins (Gunfire July 4, 1776 – Declaration of at Lexington and Concord in Independence approved. The Massachusetts was famously thirteen American colonies declare described as "the shot heard themselves no longer under round the world.”) British rule. Summer of 1778 – Benjamin Tallmadge, under orders from August 25, 1778 – Washington General Washington, established a wrote to Tallmadge, agreeing to chain of American spies on Long his choice of Abraham Woodhull Island and in New York City. as spy leader in Setauket, the point at which correspondence would cross April 1779 – Washington the Sound from Long Island to Connecticut. forwarded a vial of invisible ink to Woodhull in response 1780 – Culper Spy Ring uncovered to his concern that his letters might be information that prevented the intercepted, leading to his discovery. British from attacking the French fleet when they arrived in Newport, May 4, 1780 – as noted by Woodhull in a RI. and led to the detection of letter, Robert Townsend decided to resign Benedict Arnold’s treason. because he felt it was only a matter of time until he was uncovered. -

Benjamin Tallmadge Trail Guide.P65

Suffolk County Council, BSA The Benjamin Tallmadge Historic Trail Suffolk County Council, BSA Brookhaven, New York The starting point of this Trail is the Town of Brookhaven parking lot at Cedar Beach just off Harbor Beach Road in Mount Sinai, NY. Hikers can be safely dropped off at this loca- tion. 90% of this trail follows Town roadways which closely approximate the original route that Benjamin Tallmadge and his contingent of Light Dragoons took from Mount Sinai to the Manor of St. George in Mastic. Extreme CAUTION needs to be observed on certain heavily traveled roads. Some Town roads have little or no shoulders at all. Most roads do not have sidewalks. Scouts should hike in a single line fashion facing the oncoming traffic. They should be dressed in their Field Uniforms or brightly colored Class “B” shirt. This Trail should only be hiked in the daytime hours. Since this 21 mile long Trail is designed to be hiked over a two day period, certain pre- arrangements must be made. The overnight camping stay can be done at Cathedral Pines County Park in Middle Island. Applications must be obtained and submitted to the Suffolk County Parks Department. On Day 2, the trail veers off Smith Road in Shirley onto a ser- vice access road inside the Wertheim National Wildlife Refuge for about a mile before returning to the neighborhood roads. As a courtesy, the Wertheim Refuge would like a letter three weeks in advance informing them that you will be hiking on their property. There are no water sources along this hike so make sure you pack enough. -

A Counterintelligence Reader, Volume 1, Chapter 1

CHAPTER 1 The American Revolution and the Post-Revolutionary Era: A Historical Legacy Introduction From 1774 to 1783, the British government and its upstart American colony became locked in an increasingly bitter struggle as the Americans moved from violent protest over British colonial policies to independence As this scenario developed, intelligence and counterintelligence played important roles in Americas fight for freedom and British efforts to save its empire It is apparent that British General Thomas Gage, commander of the British forces in North America since 1763, had good intelligence on the growing rebel movement in the Massachusetts colony prior to the Battles of Lexington and Concord His highest paid spy, Dr Benjamin Church, sat in the inner circle of the small group of men plotting against the British Gage failed miserably, however, in the covert action and counterintelligence fields Gages successor, General Howe, shunned the use of intelligence assets, which impacted significantly on the British efforts General Clinton, who replaced Howe, built an admirable espionage network but by then it was too late to prevent the American colonies from achieving their independence On the other hand, George Washington was a first class intelligence officer who placed great reliance on intelligence and kept a very personal hand on his intelligence operations Washington also made excellent use of offensive counterintelligence operations but never created a unit or organization to conduct defensive counterintelligence or to coordinate its -

Immigrant Printers and the Creation of Information Networks in Revolutionary America Joseph M. Adelman Program in Early American

1 Immigrant Printers and the Creation of Information Networks in Revolutionary America Joseph M. Adelman Program in Early American Economy and Society The Library Company of Philadelphia A Paper Submitted to ―Ireland, America, and the Worlds of Mathew Carey‖ Co-Sponsored by: The McNeil Center for Early American Studies The Program in Early American Economy and Society The Library Company of Philadelphia, The University of Pennsylvania Libraries Philadelphia, PA October 27-29, 2011 *Please do not cite without permission of the author 2 This paper is a first attempt to describe the collective experience of those printers who immigrated to North America during the Revolutionary era, defined here as the period between 1756 and 1796. It suggests these printers integrated themselves into the colonial part of an imperial communications structure and then into a new national communications structure in order to achieve business success. Historians have amply demonstrated that the eighteenth century Atlantic economy relied heavily on the social and cultural capital that people amassed through their connections and networks.1 This reliance was even stronger in the printing trade because the trade depended on the circulation of news, information, and ideas to provide the raw material for its products. In order to be successful, one had to cultivate other printers, ship captains, leading commercial men, and far-flung correspondents as sources of news and literary production. Immigrants by and large started at a slight disadvantage to their native-born competitors because they for the most part lacked these connections in a North American context. On the other hand, some immigrant printers had an enormous advantage in the credit and networks they had developed in Europe, and which they parlayed into commercial and political success once they landed in North America. -

Tory David Spat of Pennsnia and the Death of Amein Priolners of War Pilip Rale Huxtff Ce4kv

185 - = Tory David Spat of Pennsnia and the Death of Amein Priolners of War Pilip Rale Huxtff Ce4kV The Old -e hAwX Amerias historical memory i very fagile. Today few recall tde fate of American naval prisoners held in New York during die Revoluionary War Of course, people of the 1780s and 1790s had a vivid scene in New York to jog thdir memories. Near tde location of the notorious British prison ships, slceletal r of dead American captives wer visible for yam Gradually destroyed by natural dements, the satred remnants were collected only in 1792. And in the eady years of the twentieth century, exavationsu for a subway tunnel dislosed still more bones assumed to belong to Anman prisoners of war' These pitiful tr aes notwithstanding, scholars have tended to attack the credibility of the numerous personal accounts-moedy memoirs-that claimed to portray conditions on board the floatig prisons. In 1909 James Ienox Banks, in an essay on Pnnsylvanian David Sproat, who was responsible for naval prisoners for some years, insisted that the memoirs presented unproved charge? of brutality V 61?N-w2 Ape 119 186 based on anti-British sentiments. Several decades later, Philip Davidson, in his well-regarded book, Propagandaand theAmerican Revolution, devoted some attention to the prison ships. He dismissed the revolutionaries' attacks as "war propaganda" and quoted some extreme examples as evidence. Davidson noted that during 1778 Elias Boudinot of New Jersey, who then investigated the matter, found the treatment of American naval prisoners to be acceptable. Significantly, Davidson's book was published in 1941, the year when the United States and Great Britain were to join in an alliance to destroy Nazi Germany.2 Although Davidson's opinion about the earlier outbreak of the Second World War is unknown, it can be guessed. -

The Culper Ring

ACTIVITY 2 REPRODUCIBLE MASTER THE CULPER RING or generations, history books have taught us that Nathan Hale was America’s first spy during the Revolutionary War, which is why his statue stands outside CIA headquarters. But, as AMC’s TURN: FWashington’s Spies reveals, there was actually a wide network of spies providing General George Washington with secret intelligence throughout the war. Unlike the eloquent Hale, however, these spies were never caught, so their identities have remained largely unknown and rarely acknowledged in history books. The Culper Ring was a group of childhood friends who were dedicated to the Patriot DISCOVERY cause and able to collect and disseminate Here is some background on Washington’s espionage operation intelligence that ultimately helped the Patriots and the members of the Culper Ring featured in AMC’s TURN: win the war. The majority of intelligence Washington’s Spies. Research the following individuals and their approach to espionage. collected by the group was about the Abraham Woodhull – A young farmer from movements of British troops and their plans for Setauket, Long Island, who concealed his New York and the surrounding area. Perhaps identity with the name Samuel Culper, Woodhull ran the group’s daily business. He frequently their most notable accomplishment was the traveled between New York and Long Island in interception of treasonous correspondence order to collect information. In TURN, Woodhull between Britain’s intelligence officer John finds himself conflicted by his loyalty to his father, Andre and Major General Benedict Arnold of a Tory, and his dedication to the Patriot cause. General George Washington’s army. -

Frederick De Bary - New York the Lure of America………

Frederick de Bary - New York The Lure of America………. “The most phenomenal migration of modern times began after the Napoleonic Wars – a tremendous movement of peoples which expanded for a full century. One phase of this movement was the ever- increasing flow of European migrants to the Americas…………..Between 1815 and 1865, some five million persons forsook the soil of Europe…………Of those who put their faith in the United States, the huge majority were Irish and Germans, not because of national characteristics, but because they were the most numerous of those who experienced the profound economic and social changes in the first half of the nineteenth century. Many left voluntarily when they saw little hope of altering their depressed legal or political status; others who tried to change this condition found it necessary to flee as exiles…………” From Robert Ernst: Immigrant Life in New York City: 1825 – 1863 - THE LURE OF AMERICA Google Books http://books.google.co.in/books?id=XQLYeUUdceoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false Samuel Frederick de Bary……. In 1851, Frederick De Bary became the sole marketing agent in the United States and in Canada for P. A. Mumm which was located in Frankfurt am-Main and G. H. Mumm et Cie which was located in Reims. De Bary also became the sole agent for the Apollinaris Company Ltd. of London, U.K. in New York and in Canada. In 1852, de Bary began his business in America in Manhattan, New York at 60 New Street; his home was at 81 Woodhull Street in Brooklyn.