And John Moffatt (University of Saskatchewan)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seth, Rabagliati, Deforge, Ollmann, Carroll, Mcfadzean Short-Listed for 2014 Doug Wright Awards

Seth, Rabagliati, DeForge, Ollmann, Carroll, McFadzean short-listed for 2014 Doug Wright Awards Members of historic “Canadian Whites” to be inducted into Hall of Fame during 10th annual ceremony March 28, 2014, Toronto, ON — The Doug Wright Awards for Canadian Cartooning are proud to announce their 2014 finalists which includes a roster of new faces, past winners and industry stalwarts. The nominees for the 2014 Doug Wright Award for Best Book are: • Palookaville #21 by Seth (Drawn and Quarterly) • Paul Joins the Scouts by Michel Rabagliati (Conundrum Press) • Science Fiction by Joe Ollmann (Conundrum Press) • Susceptible by Geneviève Castrée (Drawn and Quarterly) • Very Casual by Michael DeForge (Koyama Press) The nominees for the 2014 Doug Wright Spotlight Award (a.k.a. “The Nipper”) which recognizes Canadian cartoonists deserving of wider recognition are: • Connor Willumsen for “Calgary: Death Milks a Cow,” “Treasure Island,” “Mooncalf,” and “Passionfruit” • Dakota McFadzean for Other Stories and the Horse You Rode in On (Conundrum Press) • Patrick Kyle for Distance Mover #7 – 12, New Comics #1 - 2 • Steven Gilbert for The Journal of the Main Street Secret Lodge • Georgia Webber for Dumb # 1 – 3 And the nominees for the 2014 Pigskin Peters Award, which recognizes the best in experimental or avant-garde comics, are: • “Calgary: Death Milks a Cow” by Connor Willumsen • Flexible Tube with Stink Lines by Seth Scriver • Journal by Julie Delporte (Koyama Press) • “Out of Skin” by Emily Carroll • Very Casual by Michael DeForge (Koyama Press) A feature event of the Toronto Comic Arts Festival (TCAF), The Doug Wright Awards are pleased to announce that the pioneering artists of the Second World War “Canadian Whites” comics will be formally inducted into The Giants of the North: The Canadian Cartoonists Hall of Fame during the ceremony on Saturday May 10, 2014 in Toronto. -

Legacy Schools Reconciliaction Guide Contents

Legacy Schools ReconciliACTION Guide Contents 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WELCOME TO THE LEGACY SCHOOLS PROGRAM 5 LEGACY SCHOOLS COMMITMENT 6 BACKGROUND 10 RECONCILIACTIONS 12 SECRET PATH WEEK 13 FUNDRAISING 15 MEDIA & SOCIAL MEDIA A Message from the Families Chi miigwetch, thank you, to everyone who has supported the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund. When our families embarked upon this journey, we never imagined the potential for Gord’s telling of Chanie’s story to create a national movement that could further reconciliation and help to build a better Canada. We truly believe it’s so important for all Canadians to understand the true history of Indigenous people in Canada; including the horrific truths of what happened in the residential school system, and the strength and resilience of Indigenous culture and peoples. It’s incredible to reflect upon the beautiful gifts both Chanie & Gord were able to leave us with. On behalf of both the Downie & Wenjack families -- Chi miigwetch, thank you for joining us on this path. We are stronger together. In Unity, MIKE DOWNIE & HARRIET VISITOR Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund 3 Introduction The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) is part of Gord Downie’s legacy and embodies his commitment, and that of his family, to improving the lives of Indigenous peoples in Canada. In collaboration with the Wenjack family, the goal of the Fund is to continue the conversation that began with Chanie Wenjack’s residential school story, and to aid our collective reconciliation journey through a combination of awareness, education and connection. Our Mission Inspired by Chanie’s story and Gord’s call to action to build a better Canada, the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) aims to build cultural understanding and create a path toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. -

Annual Report 2019 / 2020 5

reconciliaction love acknowledgment forgiveness education openness recognition reflection connection love awareness truth respect hope exploration leadership forgiveness communication grace curiosity inspiration education legacy reconciliaction respect truth understanding compassion acknowledgment education reconciliaction love forgiveness respect awareness connection inspiration truth reconciliaction caring education humility openness recognition reflection connection recognition reflection curiosity acknowledgment forgiveness love acknowledgment forgiveness love exploration patience communication exploration patience communication ANNUA L caring grace curiosity hope truth REPORT legacy grace curiosity hope truth reconciliaction love humility 2019 - 2020 communication curiosity inspiration grace exploration awareness forgiveness reconciliaction curiosity inspiration grace education legacy reconciliaction respect truth understanding compassion acknowledgment education reconciliaction love forgiveness respect awareness connection inspiration truth education respect openness caring Contents Land Acknowledgement ............................................................................................. 3 Message from the Families ......................................................................................... 4 Message from CEO ...................................................................................................... 5 Our Purpose ................................................................................................................ -

Doug Wright Final Interior:Layout 1 11/11/08 12:44 PM Page 1

doug_wright_final_interior:Layout 1 11/11/08 12:44 PM Page 1 doug_wright_final_interior:Layout 1 11/11/08 12:45 PM Page 2 doug_wright_final_interior:Layout 1 11/11/08 12:45 PM Page 3 doug_wright_final_interior:Layout 1 11/11/08 12:48 PM Page 12 FLYING OFFICER DOUGLAS AUSTIN WRIGHT (above) circa 1942 to 1945. SELF–PORTRAIT (opposite) circa late 1930s. doug_wright_final_interior:Layout 1 11/11/08 12:48 PM Page 13 doug_wright_final_interior:Layout 1 11/11/08 12:49 PM Page 16 THE VIEW FROM WRIGHT’S WINDOW 2005 MansTeld street, Apartment #10, Montreal, circa 1938–40. doug_wright_final_interior:Layout 1 11/11/08 12:49 PM Page 17 doug_wright_final_interior:Layout 1 11/11/08 12:51 PM Page 20 Qis large and very polished full page strip is quite likely part of a package of sample comics which Wright sent down to the U.S. syndicates in the early 1950s. doug_wright_final_interior:Layout 1 11/11/08 12:51 PM Page 21 Creator of the internationally syndicated comic strip { FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE } hen the paper came, my dad was the ^rst to read the comics. He didn’t just read them, he studied them and encouraged me to do the same. He was particularly fond of comic art that had structure and substance and the kind of subtle wit that brought the reader into the gag the way a storyteller tells a tale. Len Norris of the Vancouver Sun was one of his favorites, Doug Wright was another. When the Star Weekly came, he would turn to Doug Wright’s Family and smile. -

REVISED AGENDA (Revision Marked with Two Asterisks**) Page 1

REVISED AGENDA (Revision marked with two asterisks**) Page 1 Toronto Public Library Board Meeting No. 5: Monday, May 15, 2017, 6:00 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. Toronto Reference Library, Board Room, 789 Yonge Street, Toronto The Chair and members gratefully acknowledge that the Toronto Public Library Board meets on the traditional territory of the Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee, and Mississaugas of New Credit First Nation, and home to many diverse Indigenous peoples. Members: Mr. Ron Carinci (Chair) Ms. Dianne LeBreton Ms. Lindsay Colley (Vice Chair) Mr. Strahan McCarten Councillor Paul Ainslie Mr. Ross Parry Councillor Sarah Doucette Ms. Archana Shah Councillor Mary Fragedakis Ms. Eva Svec Ms. Sue Graham-Nutter Closed Meeting Requirements: If the Toronto Public Library Board wants to meet in closed session (privately), a member of the Board must make a motion to do so and give the reason why the Board has to meet privately (Public Libraries Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. P.44, s. 16.1). 1. Call to Order 2. Declarations of Conflicts of Interest 3. Approval of Agenda 4. Confirmation of April 13, 2017 City Librarian’s Performance Review Committee Meeting Minutes 5. Confirmation of April 13, 2017 City Librarian’s Performance Review Committee Closed Meeting Minutes 6. Confirmation of April 18, 2017 Toronto Public Library Board Meeting Minutes 7. Confirmation of April 18, 2017 Toronto Public Library Board Closed Meeting Minutes 8. Approval of Consent Agenda Items All Consent Agenda Items (*) are considered to be routine and are recommended for approval by the Chair. They may be enacted in one motion or any item may be held for discussion. -

Get Ebooks Black Hammer Volume 1: Secret Origins Once They Were Heroes, but the Age of Heroes Has Long Since Passed

Get Ebooks Black Hammer Volume 1: Secret Origins Once they were heroes, but the age of heroes has long since passed. Banished from existence by a multiversal crisis, the old champions of Spiral City--Abraham Slam, Golden Gail, Colonel Weird, Madame Dragonfly, and Barbalien--now lead simple lives in an idyllic, timeless farming village from which there is no escape! But as they employ all of their super abilities to free themselves from this strange purgatory, a mysterious stranger works to bring them back into action for one last adventure! Collects Black Hammer #1-#6.The first chapter in Jeff Lemire (The Underwater Welder, The Complete Essex County, Animal Man) and Dean Ormston's (Lucifer) acclaimed series! Series: Black Hammer Paperback: 152 pages Publisher: Dark Horse Books (April 11, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 1616557869 ISBN-13: 978-1616557867 Product Dimensions: 6.7 x 0.3 x 10.2 inches Shipping Weight: 14.4 ounces (View shipping rates and policies) Average Customer Review: 5.0 out of 5 stars 13 customer reviews Best Sellers Rank: #22,760 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #30 in Books > Comics & Graphic Novels > Publishers > Dark Horse #143 in Books > Comics & Graphic Novels > Graphic Novels > Superheroes New York Times Bestselling author, Jeff Lemire, is the creator of the acclaimed graphic novels Sweet Tooth, Essex County, The Underwater Welder and Trillium. His upcoming projects include the original graphic novel Roughneck from Simon and Schuster, as well as the sci-fi series Descender for Image Comics (with Dustin Nguyen) and Black Hammer for Dark Horse Comics (with Dean Ormston). -

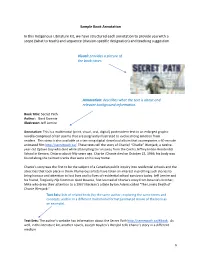

6 Sample Book Annotation in This Indigenous Literature Kit, We Have Structured Each Annotation to Provide You with a Scope

Sample Book Annotation In this Indigenous Literature Kit, we have structured each annotation to provide you with a scope (what to teach) and sequence (division-specific designation) and teaching suggestion. Visual: provides a picture of the book cover. Annotation: describes what the text is about and relevant background information. Book Title: Secret Path Author: Gord Downie Illustrator: Jeff Lemire Annotation: This is a multimodal (print, visual, oral, digital) postmodern text in an enlarged graphic novella comprised of ten poems that are poignantly illustrated to evoke strong emotion from readers. This story is also available as a ten-song digital download album that accompanies a 60-minute animated film http://secretpath.ca/. These texts tell the story of Chanie/ “Charlie” Wenjack, a twelve- year-old Ojibwe boy who died while attempting to run away from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario about fifty years ago. Charlie /Chanie died on October 22, 1966; his body was found along the railroad tracks that were on his way home. Chanie’s story was the first to be the subject of a Canadian public inquiry into residential schools and the atrocities that took place in them. Numerous artists have taken an interest in profiling such stories to bring honour and attention to lost lives and to lives of residential school survivors today. Jeff Lemire and his friend, Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, first learned of Chanie's story from Downie's brother, Mike who drew their attention to a 1967 Maclean's article by Ian Adams called "The Lonely Death of Chanie Wenjack." Text Sets: lists of related texts (by the same author; exploring the same terms and concepts; and/or in a different multimodal format (animated movie of the book as an example). -

MUNDANE INTIMACIES and EVERYDAY VIOLENCE in CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in Partial Fulfilm

MUNDANE INTIMACIES AND EVERYDAY VIOLENCE IN CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2020 © Copyright by Kaarina Louise Mikalson, 2020 Table of Contents List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v Abstract ............................................................................................................................. vii Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 Comics in Canada: A Brief History ................................................................................. 7 For Better or For Worse................................................................................................. 17 The Mundane and the Everyday .................................................................................... 24 Chapter outlines ............................................................................................................. 30 Chapter 2: .......................................................................................................................... 37 Mundane Intimacy and Slow Violence: ........................................................................... -

Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 14.1.14 Halifax Regional Council December 12, 2017 TO: Mayor Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council SUBMITTED BY: Jacques Dubé, Chief Administrative Officer DATE: November 30, 2017 SUBJECT: The Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project ORIGIN July 18, 2017 Regional Council Motion: MOVED by Mayor Savage, seconded by Councillor Outhit, that Regional Council request a staff report to: 1. Evaluate the municipality’s potential participation in the Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project, including through an annual $5,000 contribution for 5 years to the Downie Wenjack Fund; and 2. Evaluate the viability of establishing a Legacy Room within City Hall as a dedicated space for the display of aboriginal art. MOTION PUT AND PASSED UNANIMOUSLY LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Halifax Regional Municipality Charter, S.N.S. 2008, c. 39, section 79 (1) The Council may expend money required by the Municipality for … (av) a grant or contribution to … (vii) a registered Canadian charitable organization; RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that Halifax Regional Council: 1. Approve a one-time contribution in the amount of $25,000 from Account M311- Grants and Tax Concession to the Tides Canada Foundation to support cross-cultural reconciliation projects funded under the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund; …RECOMMENDATION CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 The Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project Council Report - 2 - December 12, 2017 2. Establish a Downie Wenjack Legacy Room in the Main Floor Boardroom at City Hall as per the terms of the Downie Wenjack Fund; 3. Authorize the Chief Administrative Officer to negotiate and execute an agreement to participate in the Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project with the Tides Canada Initiatives Society; 4. -

Camera Stylo 2019 Inside Final 9

Moving Forward as a Nation: Chanie Wenjack and Canadian Assimilation of Indigenous Stories ANDALAH ALI Andalah Ali is a fourth year cinema studies and English student. Her primary research interests include mediated representations of death and alterity, horror, flm noir, and psychoanalytic theory. 66 The story of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old Ojibwe boy who froze to death in 1966 while fleeing from Cecilia Jeffery Indian Residential School,1 has taken hold within Canadian arts and culture. In 2016, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the young boy’s tragic and lonely death, a group of Canadian artists, including Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, comic book artist Jeff Lemire, and filmmaker Terril Calder, created pieces inspired by the story.2 Giller Prize-winning author Joseph Boyden, too, participated in the commemoration, publishing a novella, Wenjack,3 only a few months before the literary controversy wherein his claims to Indigenous heritage were questioned, and, by many people’s estimation, disproven.4 Earlier the same year, Historica Canada released a Heritage Minute on Wenjack, also written by Boyden.5 Ostensibly, the foregrounding of such a story within a cultural institution as mainstream as the Heritage Minutes functions as a means to critically address Canadian complicity in settler-colonialism. By constituting residential schools as a sealed-off element of history, however, the Heritage Minute instead negates ongoing Canadian culpability in the settler-colonial project. Furthermore, the video’s treatment of landscape mirrors that of the garrison mentality, which is itself a colonial construct. The video deflects from discourses on Indigenous sovereignty or land rights, instead furthering an assimilationist agenda that proposes absorption of Indigenous stories, and people, into the Canadian project of nation-building. -

Residential Schools in Canada: an Education Guide

RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map of residential schools in Canada (courtesy of National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, University of Manitoba). Thomas Moore, Regina Indian Industrial School, c. 1874 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/NL-022474). “ When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that the Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.” — Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, Official report of the debates of the Table of Contents House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada, 9 May 1883, 1107–1108 Introduction: Residential Schools 2 Introduction: residential schools Message to Teachers 3 Residential schools were government-sponsored religious schools established to assimilate The Legacy of Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian society. Successive Canadian governments used Indian Residential Schools 4 legislation to strip Indigenous peoples of basic human and legal rights, dignity and integrity, Timeline 5 and to gain control over the peoples, their lands and natural rights and resources. The Indian Act, Historical Significance: first introduced in 1876, gave the Canadian government license to control almost every aspect Timeline Activity 8 of Indigenous peoples’ lives. -

1 PRESS KIT, Nina Bunjevac Updated: August 2019 [email protected] PUBLISHING HISTORY/ BOOKS • BEZIMENA, Graphic Novel

PRESS KIT, Nina Bunjevac Updated: August 2019 [email protected] PUBLISHING HISTORY/ BOOKS • BEZIMENA, graphic novel, Fantagraphics, 2019; int. language rights sold in French, Italian, German, Danish, Czech, Portuguese (Brasil), Slovenian, Spanish and Serbian • FATHERLAND, graphic novel, Jonathan Cape, 2014; translated and published in French, German, Italian, Serbian, Croatian, Slovenian, Czech, Spanish and Swedish • HEARTLESS, collection of short graphic fiction, Conundrum Press, 2012; translated and published in Serbian and French PUBLISHING HISTORY/ SELECTED ANTHOLOGIES AND PERIODICALS • Best American Comics 2016, anthology of North American graphic fiction, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, select pages from FATHERLAND/ 2016 • Le Monde Diplomatique, German edition, High Arctic Relocation, graphic fiction/ January 2016 • Taddle Creek Comics Issue, Fatherland II, graphic fiction/ winter 2015 • Best American Comics 2014, anthology of North American graphic fiction, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt/ 2015, select pages from HEARTLESS • National Post, What is Killing the Mecca of Comics? Graphic fiction/ May 2015 • ArtReview, Left, Right, Left, graphic fiction /November 2012, commissioned comic plus interview by Paul Gravett • Taddle Creek magazine, Socially Inept, graphic fiction/ summer 2012 • ELQ/Exile Literary Quarterly, August 1997, graphic fiction/ summer 2011 • BLACK, comics anthology, Waiting for Chip, graphic fiction, Coconino Press/ Italy, 2011 • Carte Blanche, Journal of the Quebec Association of Writers, Waiting for Chip/ 2011 • Le Dernier