SSHRC and the Conscientious Community: Reflecting and Acting on Indigenous Research and Reconciliation in Response to TRC Call to Action 65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 JUNO Award Nominees Updated: February 7, 2017

2017 JUNO Award Nominees Updated: February 7, 2017 JUNO FAN CHOICE (PRESENTED BY TD) Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal Belly Roc Nation*Universal Drake Cash Money*Universal Hedley Universal Justin Bieber Def Jam*Universal Ruth B Columbia*Sony Shawn Mendes Island*Universal The Strumbellas Six Shooter*Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal SINGLE OF THE YEAR Wild Things Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal One Dance ft. Wizkid & Kyla Drake Cash Money*Universal Treat You Better Shawn Mendes Island*Universal Spirits The Strumbellas Six Shooter*Universal Starboy ft. Daft Punk The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY IDLA ASSOCIATED LABEL DISTRIBUTION) Dangerous Woman Ariana Grande Republic*Universal A Head Full of Dreams Coldplay Parlophone*Warner Made in the A.M. One Direction Sony ANTI Rihanna Westbury Road*Universal This is Acting Sia RCA*Sony ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY MUSIC CANADA) Encore un Soir Céline Dion Sony Views Drake Cash Money*Universal You Want It Darker Leonard Cohen Sony Illuminate Shawn Mendes Island*Universal Starboy The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal ARTIST OF THE YEAR Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal Drake Cash Money*Universal Leonard Cohen Sony Shawn Mendes Island*Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal GROUP OF THE YEAR Arkells Arkells*Universal Billy Talent Warner Tegan and Sara Warner Bros. -

Legacy Schools Reconciliaction Guide Contents

Legacy Schools ReconciliACTION Guide Contents 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WELCOME TO THE LEGACY SCHOOLS PROGRAM 5 LEGACY SCHOOLS COMMITMENT 6 BACKGROUND 10 RECONCILIACTIONS 12 SECRET PATH WEEK 13 FUNDRAISING 15 MEDIA & SOCIAL MEDIA A Message from the Families Chi miigwetch, thank you, to everyone who has supported the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund. When our families embarked upon this journey, we never imagined the potential for Gord’s telling of Chanie’s story to create a national movement that could further reconciliation and help to build a better Canada. We truly believe it’s so important for all Canadians to understand the true history of Indigenous people in Canada; including the horrific truths of what happened in the residential school system, and the strength and resilience of Indigenous culture and peoples. It’s incredible to reflect upon the beautiful gifts both Chanie & Gord were able to leave us with. On behalf of both the Downie & Wenjack families -- Chi miigwetch, thank you for joining us on this path. We are stronger together. In Unity, MIKE DOWNIE & HARRIET VISITOR Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund 3 Introduction The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) is part of Gord Downie’s legacy and embodies his commitment, and that of his family, to improving the lives of Indigenous peoples in Canada. In collaboration with the Wenjack family, the goal of the Fund is to continue the conversation that began with Chanie Wenjack’s residential school story, and to aid our collective reconciliation journey through a combination of awareness, education and connection. Our Mission Inspired by Chanie’s story and Gord’s call to action to build a better Canada, the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) aims to build cultural understanding and create a path toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. -

Canadian Journal of Archaeology Journal Canadien D'archéologie

Canadian Journal of Archaeology Journal Canadien d’Archéologie SPECIAL ISSUE: UNSETTLING ARCHAEOLOGY Guest Edited by Lisa Hodgetts and Laura Kelvin Volume 44, 2020 • Issue 1 Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal Canadien d’Archéologie Editor-in-Chief/Rédacteur en chef Associate Editor/Rédacteur adjoint John Creese Frédéric Dussault Department of Sociology and Anthropology [[email protected]] North Dakota State University Copy Editor/Réviseure Dept. 2350, PO Box 6050, Aleksa Alaica Fargo, ND, USA 58108-6050 Department of Anthropology, Ph: (701) 231-7434 University of Toronto [[email protected]] [[email protected]] Editorial Assistant/Adjointe à la rédaction Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus Cheryl Takahashi Katherine Patton Takahashi Design Anthropology Building, University of Toronto 4358 Island Hwy. S. 19 Russell Street, Toronto, ON M5S 2S2 Courtenay, BC V9N 9R9 Ph: (416) 946-3589 Ph: (250) 650-3766; [[email protected]] [[email protected]] EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD / COMITÉ CONSULTATIF DE RÉDACTION • Arctic—Peter Dawson, Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary • Subarctic—Scott Hamilton, Department of Anthropology, Lakehead University • Pacific Northwest—Alan McMillan, Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University • Prairie Region—Jack Brink, Royal Alberta Museum, Edmonton • Ontario—Neal Ferris, Department of Anthropology, University of Western Ontario • Quebec—André Costopoulos, Department of Anthropology, McGill University • Atlantic—Michael -

REVISED AGENDA (Revision Marked with Two Asterisks**) Page 1

REVISED AGENDA (Revision marked with two asterisks**) Page 1 Toronto Public Library Board Meeting No. 5: Monday, May 15, 2017, 6:00 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. Toronto Reference Library, Board Room, 789 Yonge Street, Toronto The Chair and members gratefully acknowledge that the Toronto Public Library Board meets on the traditional territory of the Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee, and Mississaugas of New Credit First Nation, and home to many diverse Indigenous peoples. Members: Mr. Ron Carinci (Chair) Ms. Dianne LeBreton Ms. Lindsay Colley (Vice Chair) Mr. Strahan McCarten Councillor Paul Ainslie Mr. Ross Parry Councillor Sarah Doucette Ms. Archana Shah Councillor Mary Fragedakis Ms. Eva Svec Ms. Sue Graham-Nutter Closed Meeting Requirements: If the Toronto Public Library Board wants to meet in closed session (privately), a member of the Board must make a motion to do so and give the reason why the Board has to meet privately (Public Libraries Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. P.44, s. 16.1). 1. Call to Order 2. Declarations of Conflicts of Interest 3. Approval of Agenda 4. Confirmation of April 13, 2017 City Librarian’s Performance Review Committee Meeting Minutes 5. Confirmation of April 13, 2017 City Librarian’s Performance Review Committee Closed Meeting Minutes 6. Confirmation of April 18, 2017 Toronto Public Library Board Meeting Minutes 7. Confirmation of April 18, 2017 Toronto Public Library Board Closed Meeting Minutes 8. Approval of Consent Agenda Items All Consent Agenda Items (*) are considered to be routine and are recommended for approval by the Chair. They may be enacted in one motion or any item may be held for discussion. -

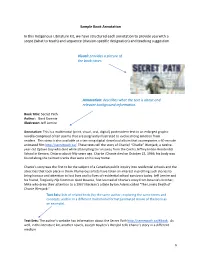

6 Sample Book Annotation in This Indigenous Literature Kit, We Have Structured Each Annotation to Provide You with a Scope

Sample Book Annotation In this Indigenous Literature Kit, we have structured each annotation to provide you with a scope (what to teach) and sequence (division-specific designation) and teaching suggestion. Visual: provides a picture of the book cover. Annotation: describes what the text is about and relevant background information. Book Title: Secret Path Author: Gord Downie Illustrator: Jeff Lemire Annotation: This is a multimodal (print, visual, oral, digital) postmodern text in an enlarged graphic novella comprised of ten poems that are poignantly illustrated to evoke strong emotion from readers. This story is also available as a ten-song digital download album that accompanies a 60-minute animated film http://secretpath.ca/. These texts tell the story of Chanie/ “Charlie” Wenjack, a twelve- year-old Ojibwe boy who died while attempting to run away from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario about fifty years ago. Charlie /Chanie died on October 22, 1966; his body was found along the railroad tracks that were on his way home. Chanie’s story was the first to be the subject of a Canadian public inquiry into residential schools and the atrocities that took place in them. Numerous artists have taken an interest in profiling such stories to bring honour and attention to lost lives and to lives of residential school survivors today. Jeff Lemire and his friend, Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, first learned of Chanie's story from Downie's brother, Mike who drew their attention to a 1967 Maclean's article by Ian Adams called "The Lonely Death of Chanie Wenjack." Text Sets: lists of related texts (by the same author; exploring the same terms and concepts; and/or in a different multimodal format (animated movie of the book as an example). -

Camera Stylo 2019 Inside Final 9

Moving Forward as a Nation: Chanie Wenjack and Canadian Assimilation of Indigenous Stories ANDALAH ALI Andalah Ali is a fourth year cinema studies and English student. Her primary research interests include mediated representations of death and alterity, horror, flm noir, and psychoanalytic theory. 66 The story of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old Ojibwe boy who froze to death in 1966 while fleeing from Cecilia Jeffery Indian Residential School,1 has taken hold within Canadian arts and culture. In 2016, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the young boy’s tragic and lonely death, a group of Canadian artists, including Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, comic book artist Jeff Lemire, and filmmaker Terril Calder, created pieces inspired by the story.2 Giller Prize-winning author Joseph Boyden, too, participated in the commemoration, publishing a novella, Wenjack,3 only a few months before the literary controversy wherein his claims to Indigenous heritage were questioned, and, by many people’s estimation, disproven.4 Earlier the same year, Historica Canada released a Heritage Minute on Wenjack, also written by Boyden.5 Ostensibly, the foregrounding of such a story within a cultural institution as mainstream as the Heritage Minutes functions as a means to critically address Canadian complicity in settler-colonialism. By constituting residential schools as a sealed-off element of history, however, the Heritage Minute instead negates ongoing Canadian culpability in the settler-colonial project. Furthermore, the video’s treatment of landscape mirrors that of the garrison mentality, which is itself a colonial construct. The video deflects from discourses on Indigenous sovereignty or land rights, instead furthering an assimilationist agenda that proposes absorption of Indigenous stories, and people, into the Canadian project of nation-building. -

2017 JUNO GALA Dinner & Award Winners

2017 JUNO GALA Dinner & Award Winners April 1, 2017 SINGLE OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY LIVE NATION CANADA) Hotel Paranoia Jazz Cartier Universal Spirits The Strumbellas Six Shooter*Universal DANCE RECORDING OF THE YEAR INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY IDLA Off the Ground ft. Shae Jacobs Bit Funk PhysiCal Presents*Universal ASSOCIATED LABEL DISTRIBUTION) A Head Full of DreaMs Coldplay Parlophone*Warner R&B/SOUL RECORDING OF THE YEAR Starboy The Weeknd The WeeknD XO*Universal ARTIST OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY TD) Leonard Cohen Sony REGGAE RECORDING OF THE YEAR Siren Exco Levi Reggaeville*Independent BREAKTHROUGH GROUP OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY FACTOR, THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA, CANADA’S PRIVATE RADIO BROADCASTERS, INDIGENOUS MUSIC ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY AND RADIO STARMAKER FUND) ABORIGINAL PEOPLES TELEVISION NETWORK) The Dirty Nil Dine Alone*Universal Tiny Hands Quantum Tangle Coax*Independent ADULT ALTERNATIVE ALBUM OF THE YEAR CONTEMPORARY ROOTS ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY Secret Path Gord Downie Arts & Crafts*Universal NATIONAL ARTS CENTRE) Earthly Days William Prince InDepenDent ALTERNATIVE ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY LONG & MCQUADE) TRADITIONAL ROOTS ALBUM OF THE YEAR Touch July Talk Sleepless*Universal Secret Victory The East Pointers The East Pointers*Fontana North ROCK ALBUM OF THE YEAR BLUES ALBUM OF THE YEAR Man Machine PoeM The Tragically Hip THE InCorporateD*Universal Ride The One Paul ReddiCk Stony Plain*Warner VOCAL JAZZ ALBUM OF THE YEAR CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL ALBUM OF THE YEAR Bria Bria Skonberg Sony Hootenanny! Tim Neufeld & the Glory Boys InDepenDent JAZZ ALBUM OF THE YEAR: SOLO WORLD MUSIC ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY CANADA Written in the Rocks Renee Rosnes Smoke Sessions*RED COUNCIL FOR THE ARTS) Okavango African Orchestra Okavango African Orchestra JAZZ ALBUM OF THE YEAR: GROUP (SPONSORED BY STINGRAY MUSIC) InDepenDent Twenty Metalwood Cellar Live*MVD JACK RICHARDSON PRODUCER OF THE YEAR INSTRUMENTAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR A Tribe Called Red “R.E.D. -

Title: Song Analysis

Janine Pelletier, 2019 Werklund Graduate Title: Song Analysis - “We are the Halluci Nation” by A Tribe Called Red Subject: ELA 10, ELA 20, ELA 30 Time: 50 minutes Janine Pelletier was born in Calgary, Alberta. She has a life-long passion for literature and Indigenous studies, and strives to create inclusive, engaging learning activities with real world connections to enable her students to learn about the subject, themselves, and the world around them. Resources used and Song: “We Are the Halluci Nation” by A Tribe Called Red possible concerns Author/creator - A Tribe Called Red is an Indigenous DJ group out of and/or literature Ottawa, Canada made of 2 members, Bear Witness background and 2oolman. “They are part of a vital new generation of artists making a cultural and social impact in Canada alongside a renewed Aboriginal rights movement called Idle No More”. ("Press Kit - A Tribe Called Red", 2020). They have been producing music since 2008, and have a Juno win and a Polaris Music Prize short list appearance.. Their sound is a mix of modern hip-hop, traditional pow wow drums and vocals, blended with edgy electronic music production styles. - “The Halluci Nation [album] is a concept given to them by one of their idols, John Trudell, a renowned one-time leader in the American Indian Movement... it was written to include a broader audience of all races and backgrounds in promoting social justice. ("A Tribe Called Red The Halluci Nation Is Real", 2020) UPE course Literacy, Language, and Culture: connections (not - This lesson plan encourages students to view popular exhaustive) media as a text that can be analyzed to gain insight into different cultures. -

Indigenous Literature Kit: Growing Our Collective Understanding of Truth and Reconciliation

Indigenous Literature Kit: Growing Our Collective Understanding of Truth and Reconciliation Kindergarten - Grade 12 Billie-Jo Grant, Vincent J Maloney Junior High School Charlotte Kirchner, Vincent J Maloney Junior High School Phyllis Kelly, JJ Nearing Elementary School Nicole Wenger, JJ Nearing Elementary School Rhonda Nixon, Division Office, Deputy Superintendent Yvonne Stang, Division Office, Literacy and ELL Consultant A Collaborative Professional Learning Project Copyright © 2021, 2017 by Greater St. Albert School District (GSACRD), Edmonton Regional Learning Consortium (ERLC), and St. Albert-Sturgeon Regional Collaborative Service Delivery region (RCSD) For more information, contact: Rhonda Nixon, Deputy Superintendent Greater St. Albert Catholic School Division (GSACRD) 6 St. Vital Avenue St. Albert, Alberta T8N 1K2 Ph: 780-459-7711 Yvonne Stang, Literacy and ELL Consultant Greater St. Albert Catholic School Division (GSACRD) 6 St. Vital Avenue St. Albert, Alberta T8N 1K2 Ph: 780-459-7711 2 Acknowledgements This collaborative project began with a mission – to create a professional learning resource that would support educators to grow in their collective understanding of Truth and Reconciliation. In the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (2012) report, the Canadian government defined “reconciliation” as learning what it means to establish and maintain mutually respectful relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. To that end, there must be awareness of the past, acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour (pp. 6–7). The TRC presented 94 Calls to Action that outline concrete steps that can be taken to begin the process of reconciliation, and we focused on Education for Reconciliation, 62-65 (pp. -

The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund

Confidential 2021 Competition Final Round The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund May 11, 2021 The Request for Proposals in this document was developed for the Student Evaluation Case Competition for educational purposes. It does not entail any commitment on the part of the Canadian Evaluation Society (CES), the Canadian Evaluation Society Educational Fund (CESEF), The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund, or any related sponsor or service delivery partner. We thank The Gord Downie & Wenjack Fund for graciously agreeing to participate in the final round of the 2021 competition. Thanks to Lisa Prinn, Manager, Education and Activation and Sarah Midanik, President and CEO for their input in preparing this case. The Case Competition is proudly sponsored by: Confidential Introduction Congratulations to all three teams for qualifying for the Final Round of the 2021 CES/CESEF Student Evaluation Case Competition! Your consulting firm has been invited to respond to the attached Request for Proposals (RFP) issued by The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) to tell the story of how DWF’s activities have contributed to positive impacts on the lives of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. The charity, supported by an advisory group of external evaluation experts, has requested a briefing from each firm on their proposal. Your proposal should demonstrate your understanding of the assignment and include a logic model, a proposed methodology, an evaluation matrix, a mitigation strategy to address anticipated evaluation challenges and a discussion of an evaluation competency that is important for a successful evaluation of this organization.1 Section 2.2 of the RFP identifies the proposal requirements in more detail. -

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada This report is in the public domain. Anyone may, without charge or request for permission, reproduce all or part of this report. 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Website: www.trc.ca Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future : summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Issued also in French under title: Honorer la vérité, réconcilier pour l’avenir, sommaire du rapport final de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada. Electronic monograph in PDF format. Issued also in printed form. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-660-02078-5 Cat. no.: IR4-7/2015E-PDF 1. Native peoples--Canada--Residential schools. 2. Native peoples—Canada--History. 3. Native peoples--Canada--Social conditions. 4. Native peoples—Canada--Government relations. 5. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 6. Truth commissions--Canada. I. Title. II. Title: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. E96.5 T78 2015 971.004’97 C2015-980024-2 Contents Preface ........................................................................................................ -

Music and Belonging / Musique Et Appartenance

Canada 150: Music and Belonging / Musique et appartenance Joint meeting / Congrès mixte Canadian Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres / Association canadienne des bibliothèques, archives et centres de documentation musicaux Canadian Society for Traditional Music / Société canadienne pour les traditions musicales Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes International Association for the Study of Popular Music, Canada Branch Faculty of Music University of Toronto 25-27 May 2017 / 25-27 mai 2017 Welcome / Bienvenue The Faculty of Music at the University of Toronto is pleased to host the conference Canada 150: Music and Belonging / Musique et appartenance from May 25th to May 27th, 2017. This meeting brings together four Canadian scholarly societies devoted to music: CAML / ACBM (Canadian Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres / Association canadienne des bibliothèques, archives et centres de documentation musicaux), CSTM / SCTM (Canadian Society for Traditional Music / Société canadienne pour les traditions musicales), IASPM Canada (International Association for the Study of Popular Music, Canada Branch), and MusCan (Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes). We are expecting 300 people to attend the conference. As you will see in this program, there will be scholarly papers (ca. 200 of them), recitals, keynote speeches, workshops, an open mic session and a dance party – something for everyone. The multiple award winning Gryphon Trio will be giving a free recital for conference delegates on Friday evening, May 26th from 7:00 to 8:15 pm. Visitors also have the opportunity to take in many other Toronto events this weekend: music festivals by the Royal Conservatory of Music and CBC; concerts by Norah Jones, Rheostatics, The Weeknd, and the Toronto Symphony; a Toronto Blue Jays baseball game; the Inside Out LGBT Film Festival, and a host of other events at venues large and small across the city.