Simple Binding Energy Computer Modelling in the Classroom (Part 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHEM 1412. Chapter 21. Nuclear Chemistry (Homework) Ky

CHEM 1412. Chapter 21. Nuclear Chemistry (Homework) Ky Multiple Choice Identify the choice that best completes the statement or answers the question. ____ 1. Consider the following statements about the nucleus. Which of these statements is false? a. The nucleus is a sizable fraction of the total volume of the atom. b. Neutrons and protons together constitute the nucleus. c. Nearly all the mass of an atom resides in the nucleus. d. The nuclei of all elements have approximately the same density. e. Electrons occupy essentially empty space around the nucleus. ____ 2. A term that is used to describe (only) different nuclear forms of the same element is: a. isotopes b. nucleons c. shells d. nuclei e. nuclides ____ 3. Which statement concerning stable nuclides and/or the "magic numbers" (such as 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82 or 128) is false? a. Nuclides with their number of neutrons equal to a "magic number" are especially stable. b. The existence of "magic numbers" suggests an energy level (shell) model for the nucleus. c. Nuclides with the sum of the numbers of their protons and neutrons equal to a "magic number" are especially stable. d. Above atomic number 20, the most stable nuclides have more protons than neutrons. e. Nuclides with their number of protons equal to a "magic number" are especially stable. ____ 4. The difference between the sum of the masses of the electrons, protons and neutrons of an atom (calculated mass) and the actual measured mass of the atom is called the ____. a. isotopic mass b. -

![Arxiv:1901.01410V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 1 Feb 2021 Mental Information Is Available, and One Has to Rely Strongly on Theoretical Predictions for Nuclear Properties](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8159/arxiv-1901-01410v3-astro-ph-he-1-feb-2021-mental-information-is-available-and-one-has-to-rely-strongly-on-theoretical-predictions-for-nuclear-properties-508159.webp)

Arxiv:1901.01410V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 1 Feb 2021 Mental Information Is Available, and One Has to Rely Strongly on Theoretical Predictions for Nuclear Properties

Origin of the heaviest elements: The rapid neutron-capture process John J. Cowan∗ HLD Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Oklahoma, 440 W. Brooks St., Norman, OK 73019, USA Christopher Snedeny Department of Astronomy, University of Texas, 2515 Speedway, Austin, TX 78712-1205, USA James E. Lawlerz Physics Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1150 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706-1390, USA Ani Aprahamianx and Michael Wiescher{ Department of Physics and Joint Institute for Nuclear Astrophysics, University of Notre Dame, 225 Nieuwland Science Hall, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA Karlheinz Langanke∗∗ GSI Helmholtzzentrum f¨urSchwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany and Institut f¨urKernphysik (Theoriezentrum), Fachbereich Physik, Technische Universit¨atDarmstadt, Schlossgartenstraße 2, 64298 Darmstadt, Germany Gabriel Mart´ınez-Pinedoyy GSI Helmholtzzentrum f¨urSchwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany; Institut f¨urKernphysik (Theoriezentrum), Fachbereich Physik, Technische Universit¨atDarmstadt, Schlossgartenstraße 2, 64298 Darmstadt, Germany; and Helmholtz Forschungsakademie Hessen f¨urFAIR, GSI Helmholtzzentrum f¨urSchwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany Friedrich-Karl Thielemannzz Department of Physics, University of Basel, Klingelbergstrasse 82, 4056 Basel, Switzerland and GSI Helmholtzzentrum f¨urSchwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany (Dated: February 2, 2021) The production of about half of the heavy elements found in nature is assigned to a spe- cific astrophysical nucleosynthesis process: the rapid neutron capture process (r-process). Although this idea has been postulated more than six decades ago, the full understand- ing faces two types of uncertainties/open questions: (a) The nucleosynthesis path in the nuclear chart runs close to the neutron-drip line, where presently only limited experi- arXiv:1901.01410v3 [astro-ph.HE] 1 Feb 2021 mental information is available, and one has to rely strongly on theoretical predictions for nuclear properties. -

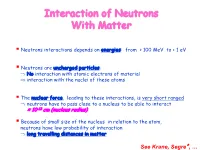

Interaction of Neutrons with Matter

Interaction of Neutrons With Matter § Neutrons interactions depends on energies: from > 100 MeV to < 1 eV § Neutrons are uncharged particles: Þ No interaction with atomic electrons of material Þ interaction with the nuclei of these atoms § The nuclear force, leading to these interactions, is very short ranged Þ neutrons have to pass close to a nucleus to be able to interact ≈ 10-13 cm (nucleus radius) § Because of small size of the nucleus in relation to the atom, neutrons have low probability of interaction Þ long travelling distances in matter See Krane, Segre’, … While bound neutrons in stable nuclei are stable, FREE neutrons are unstable; they undergo beta decay with a lifetime of just under 15 minutes n ® p + e- +n tn = 885.7 ± 0.8 s ≈ 14.76 min Long life times Þ before decaying possibility to interact Þ n physics … x Free neutrons are produced in nuclear fission and fusion x Dedicated neutron sources like research reactors and spallation sources produce free neutrons for the use in irradiation neutron scattering exp. 33 N.B. Vita media del protone: tp > 1.6*10 anni età dell’universo: (13.72 ± 0,12) × 109 anni. beta decay can only occur with bound protons The neutron lifetime puzzle From 2016 Istitut Laue-Langevin (ILL, Grenoble) Annual Report A. Serebrov et al., Phys. Lett. B 605 (2005) 72 A.T. Yue et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 111 (2013) 222501 Z. Berezhiani and L. Bento, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96 (2006) 081801 G.L. Greene and P. Geltenbort, Sci. Am. 314 (2016) 36 A discrepancy of more than 8 seconds !!!! https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/neutro -

Spontaneous Fission

13) Nuclear fission (1) Remind! Nuclear binding energy Nuclear binding energy per nucleon V - Sum of the masses of nucleons is bigger than the e M / nucleus of an atom n o e l - Difference: nuclear binding energy c u n r e p - Energy can be gained by fusion of light elements y g r e or fission of heavy elements n e g n i d n i B Mass number 157 13) Nuclear fission (2) Spontaneous fission - heavy nuclei are instable for spontaneous fission - according to calculations this should be valid for all nuclei with A > 46 (Pd !!!!) - practically, a high energy barrier prevents the lighter elements from fission - spontaneous fission is observed for elements heavier than actinium - partial half-lifes for 238U: 4,47 x 109 a (α-decay) 9 x 1015 a (spontaneous fission) - Sponatenous fission of uranium is practically the only natural source for technetium - contribution increases with very heavy elements (99% with 254Cf) 158 1 13) Nuclear fission (3) Potential energy of a nucleus as function of the deformation (A, B = energy barriers which represent fission barriers Saddle point - transition state of a nucleus is determined by its deformation - almost no deformation in the ground state - fission barrier is higher by 6 MeV Ground state Point of - tunneling of the barrier at spontaneous fission fission y g r e n e l a i t n e t o P 159 13) Nuclear fission (4) Artificially initiated fission - initiated by the bombardment with slow (thermal neutrons) - as chain reaction discovered in 1938 by Hahn, Meitner and Strassmann - intermediate is a strongly deformed -

Production and Properties Towards the Island of Stability

This is an electronic reprint of the original article. This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail. Author(s): Leino, Matti Title: Production and properties towards the island of stability Year: 2016 Version: Please cite the original version: Leino, M. (2016). Production and properties towards the island of stability. In D. Rudolph (Ed.), Nobel Symposium NS 160 - Chemistry and Physics of Heavy and Superheavy Elements (Article 01002). EDP Sciences. EPJ Web of Conferences, 131. https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201613101002 All material supplied via JYX is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, and duplication or sale of all or part of any of the repository collections is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for your research use or educational purposes in electronic or print form. You must obtain permission for any other use. Electronic or print copies may not be offered, whether for sale or otherwise to anyone who is not an authorised user. EPJ Web of Conferences 131, 01002 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201613101002 Nobel Symposium NS160 – Chemistry and Physics of Heavy and Superheavy Elements Production and properties towards the island of stability Matti Leino Department of Physics, University of Jyväskylä, PO Box 35, 40014 University of Jyväskylä, Finland Abstract. The structure of the nuclei of the heaviest elements is discussed with emphasis on single-particle properties as determined by decay and in- beam spectroscopy. The basic features of production of these nuclei using fusion evaporation reactions will also be discussed. 1. Introduction In this short review, some examples of nuclear structure physics and experimental methods relevant for the study of the heaviest elements will be presented. -

Fission and Fusion Can Yield Energy

Nuclear Energy Nuclear energy can also be separated into 2 separate forms: nuclear fission and nuclear fusion. Nuclear fusion is the splitting of large atomic nuclei into smaller elements releasing energy, and nuclear fusion is the joining of two small atomic nuclei into a larger element and in the process releasing energy. The mass of a nucleus is always less than the sum of the individual masses of the protons and neutrons which constitute it. The difference is a measure of the nuclear binding energy which holds the nucleus together (Figure 1). As figures 1 and 2 below show, the energy yield from nuclear fusion is much greater than nuclear fission. Figure 1 2 Nuclear binding energy = ∆mc For the alpha particle ∆m= 0.0304 u which gives a binding energy of 28.3 MeV. (Figure from: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/nucene/nucbin.html ) Fission and fusion can yield energy Figure 2 (Figure from: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/nucene/nucbin.html) Nuclear fission When a neutron is fired at a uranium-235 nucleus, the nucleus captures the neutron. It then splits into two lighter elements and throws off two or three new neutrons (the number of ejected neutrons depends on how the U-235 atom happens to split). The two new atoms then emit gamma radiation as they settle into their new states. (John R. Huizenga, "Nuclear fission", in AccessScience@McGraw-Hill, http://proxy.library.upenn.edu:3725) There are three things about this induced fission process that make it especially interesting: 1) The probability of a U-235 atom capturing a neutron as it passes by is fairly high. -

1 Chapter 16 Stable and Radioactive Isotopes Jim Murray 5/7/01 Univ

Chapter 16 Stable and Radioactive Isotopes Jim Murray 5/7/01 Univ. Washington Each atomic element (defined by its number of protons) comes in different flavors, depending on the number of neutrons. Most elements in the periodic table exist in more than one isotope. Some are stable and some are radioactive. Scientists have tallied more than 3600 isotopes, the majority are radioactive. The Isotopes Project at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab in California has a web site (http://ie.lbl.gov/toi.htm) that gives detailed information about all the isotopes. Stable and radioactive isotopes are the most useful class of tracers available to geochemists. In almost all cases the distributions of these isotopes have been used to study oceanographic processes controlling the distributions of the elements. Radioactive isotopes are especially useful because they provide a way to put time into geochemical models. The chemical characteristic of an element is determined by the number of protons in its nucleus. Different elements can have different numbers of neutrons and thus atomic weights (the sum of protons plus neutrons). The atomic weight is equal to the sum of protons plus neutrons. The chart of the nuclides (protons versus neutrons) for elements 1 (Hydrogen) through 12 (Magnesium) is shown in Fig. 16-1. The Valley of Stability represents nuclides stable relative to decay. Examples: Atomic Protons Neutrons % Abundance Weight (Atomic Number) Carbon 12C 6P 6N 98.89 13C 6P 7N 1.11 14C 6P 8N 10-10 Oxygen 16O 8P 8N 99.76 17O 8P 9N 0.024 18O 8P 10N 0.20 Several light elements such as H, C, N, O, and S have more than one stable isotope form, which show variable abundances in natural samples. -

Quest for Superheavy Nuclei Began in the 1940S with the Syn Time It Takes for Half of the Sample to Decay

FEATURES Quest for superheavy nuclei 2 P.H. Heenen l and W Nazarewicz -4 IService de Physique Nucleaire Theorique, U.L.B.-C.P.229, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium 2Department ofPhysics, University ofTennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996 3Physics Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831 4Institute ofTheoretical Physics, University ofWarsaw, ul. Ho\.za 69, PL-OO-681 Warsaw, Poland he discovery of new superheavy nuclei has brought much The superheavy elements mark the limit of nuclear mass and T excitement to the atomic and nuclear physics communities. charge; they inhabit the upper right corner of the nuclear land Hopes of finding regions of long-lived superheavy nuclei, pre scape, but the borderlines of their territory are unknown. The dicted in the early 1960s, have reemerged. Why is this search so stability ofthe superheavy elements has been a longstanding fun important and what newknowledge can it bring? damental question in nuclear science. How can they survive the Not every combination ofneutrons and protons makes a sta huge electrostatic repulsion? What are their properties? How ble nucleus. Our Earth is home to 81 stable elements, including large is the region of superheavy elements? We do not know yet slightly fewer than 300 stable nuclei. Other nuclei found in all the answers to these questions. This short article presents the nature, although bound to the emission ofprotons and neutrons, current status ofresearch in this field. are radioactive. That is, they eventually capture or emit electrons and positrons, alpha particles, or undergo spontaneous fission. Historical Background Each unstable isotope is characterized by its half-life (T1/2) - the The quest for superheavy nuclei began in the 1940s with the syn time it takes for half of the sample to decay. -

Nuclear Binding & Stability

Nuclear Binding & Stability Stanley Yen TRIUMF UNITS: ENERGY Energy measured in electron-Volts (eV) 1 volt battery boosts energy of electrons by 1 eV 1 volt -19 battery 1 e-Volt = 1.6x10 Joule 1 MeV = 106 eV 1 GeV = 109 eV Recall that atomic and molecular energies ~ eV nuclear energies ~ MeV UNITS: MASS From E = mc2 m = E / c2 so we measure masses in MeV/c2 1 MeV/c2 = 1.7827 x 10 -30 kg Frequently, we get lazy and just set c=1, so that we measure masses in MeV e.g. mass of electron = 0.511 MeV mass of proton = 938.272 MeV mass of neutron=939.565 MeV Also widely used unit of mass is the atomic mass unit (amu or u) defined so that Mass(12C atom) = 12 u -27 1 u = 931.494 MeV = 1.6605 x 10 kg nucleon = proton or neutron “nuclide” means one particular nuclear species, e.g. 7Li and 56Fe are two different nuclides There are 4 fundamental types of forces in the universe. 1. Gravity – very weak, negligible for nuclei except for neutron stars 2. Electromagnetic forces – Coulomb repulsion tends to force protons apart ) 3. Strong nuclear force – binds nuclei together; short-ranged 4. Weak nuclear force – causes nuclear beta decay, almost negligible compared to the strong and EM forces. How tightly a nucleus is bound together is mostly an interplay between the attractive strong force and the repulsive electromagnetic force. Let's make a scatterplot of all the stable nuclei, with proton number Z versus neutron number N. -

Nuclear Physics

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 22.02 INTRODUCTION to APPLIED NUCLEAR PHYSICS Spring 2012 Prof. Paola Cappellaro Nuclear Science and Engineering Department [This page intentionally blank.] 2 Contents 1 Introduction to Nuclear Physics 5 1.1 Basic Concepts ..................................................... 5 1.1.1 Terminology .................................................. 5 1.1.2 Units, dimensions and physical constants .................................. 6 1.1.3 Nuclear Radius ................................................ 6 1.2 Binding energy and Semi-empirical mass formula .................................. 6 1.2.1 Binding energy ................................................. 6 1.2.2 Semi-empirical mass formula ......................................... 7 1.2.3 Line of Stability in the Chart of nuclides ................................... 9 1.3 Radioactive decay ................................................... 11 1.3.1 Alpha decay ................................................... 11 1.3.2 Beta decay ................................................... 13 1.3.3 Gamma decay ................................................. 15 1.3.4 Spontaneous fission ............................................... 15 1.3.5 Branching Ratios ................................................ 15 2 Introduction to Quantum Mechanics 17 2.1 Laws of Quantum Mechanics ............................................. 17 2.2 States, observables and eigenvalues ......................................... 18 2.2.1 Properties of eigenfunctions ......................................... -

The Delimiting/Frontier Lines of the Constituents of Matter∗

The delimiting/frontier lines of the constituents of matter∗ Diógenes Galetti1 and Salomon S. Mizrahi2 1Instituto de Física Teórica, Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), São Paulo, SP, Brasily 2Departamento de Física, CCET, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, SP, Brasilz (Dated: October 23, 2019) Abstract Looking at the chart of nuclides displayed at the URL of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) [1] – that contains all the known nuclides, the natural and those produced artificially in labs – one verifies the existence of two, not quite regular, delimiting lines between which dwell all the nuclides constituting matter. These lines are established by the highly unstable radionuclides located the most far away from those in the central locus, the valley of stability. Here, making use of the “old” semi-empirical mass formula for stable nuclides together with the energy-time uncertainty relation of quantum mechanics, by a simple calculation we show that the obtained frontier lines, for proton and neutron excesses, present an appreciable agreement with the delimiting lines. For the sake of presenting a somewhat comprehensive panorama of the matter in our Universe and their relation with the frontier lines, we narrate, in brief, what is currently known about the astrophysical nucleogenesis processes. Keywords: chart of nuclides, nucleogenesis, nuclide mass formula, valley/line of stability, energy-time un- certainty relation, nuclide delimiting/frontier lines, drip lines arXiv:1909.07223v2 [nucl-th] 22 Oct 2019 ∗ This manuscript is based on an article that was published in Brazilian portuguese language in the journal Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Física, 2018, 41, e20180160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/ 1806-9126-rbef-2018-0160. -

The R-Process of Stellar Nucleosynthesis: Astrophysics and Nuclear Physics Achievements and Mysteries

The r-process of stellar nucleosynthesis: Astrophysics and nuclear physics achievements and mysteries M. Arnould, S. Goriely, and K. Takahashi Institut d'Astronomie et d'Astrophysique, Universit´eLibre de Bruxelles, CP226, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium Abstract The r-process, or the rapid neutron-capture process, of stellar nucleosynthesis is called for to explain the production of the stable (and some long-lived radioac- tive) neutron-rich nuclides heavier than iron that are observed in stars of various metallicities, as well as in the solar system. A very large amount of nuclear information is necessary in order to model the r-process. This concerns the static characteristics of a large variety of light to heavy nuclei between the valley of stability and the vicinity of the neutron-drip line, as well as their beta-decay branches or their reactivity. Fission probabilities of very neutron-rich actinides have also to be known in order to determine the most massive nuclei that have a chance to be involved in the r-process. Even the properties of asymmetric nuclear matter may enter the problem. The enormously challenging experimental and theoretical task imposed by all these requirements is reviewed, and the state-of-the-art development in the field is presented. Nuclear-physics-based and astrophysics-free r-process models of different levels of sophistication have been constructed over the years. We review their merits and their shortcomings. The ultimate goal of r-process studies is clearly to identify realistic sites for the development of the r-process. Here too, the challenge is enormous, and the solution still eludes us.