Environmental Matters and Disability Issues in Disney's Animations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Indigenous Body As Animated Palimpsest Michelle Johnson Phd Candidate, Dance Studies | York University, Toronto, Canada

CONTINGENT HORIZONS The York University Student Journal of Anthropology VOLUME 5, NUMBER 1 (2019) OBJECTS “Not That You’re a Savage” The Indigenous Body as Animated Palimpsest Michelle Johnson PhD candidate, Dance Studies | York University, Toronto, Canada Contingent Horizons: The York University Student Journal of Anthropology. 2019. 5(1):45–62. First published online July 12, 2019. Contingent Horizons is available online at ch.journals.yorku.ca. Contingent Horizons is an annual open-access, peer-reviewed student journal published by the department of anthropology at York University, Toronto, Canada. The journal provides a platform for graduate and undergraduate students of anthropology to publish their outstanding scholarly work in a peer-reviewed academic forum. Contingent Horizons is run by a student editorial collective and is guided by an ethos of social justice, which informs its functioning, structure, and policies. Contingent Horizons’ website provides open-access to the journal’s published articles. ISSN 2292-7514 (Print) ISSN 2292-6739 (Online) editorial collective Meredith Evans, Nadine Ryan, Isabella Chawrun, Divy Puvimanasinghe, and Katie Squires cover photo Jordan Hodgins “Not That You’re a Savage” The Indigenous Body as Animated Palimpsest MICHELLE JOHNSON PHD CANDIDATE, DANCE STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY, TORONTO, CANADA In 1995, Disney Studios released Pocahontas, its first animated feature based on a historical figure and featuring Indigenous characters. Amongst mixed reviews, the film provoked criti- cism regarding historical inaccuracy, cultural disrespect, and the sexualization of the titular Pocahontas as a Native American woman. Over the following years the studio has released a handful of films centered around Indigenous cultures, rooted in varying degrees of reality and fantasy. -

The Disney Strike of 1941: from the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, Ljohnson [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2008 The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Labor Relations Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Lisa, "The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective" (2008). Honors Projects Overview. 17. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/17 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective An Undergraduate Honors Project Presented By Lisa Johnson To The Department of History Approved: Project Advisor Date Chair, Department Honors Committee Date Department Chair Date The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective By Lisa Johnson An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of History The School of the Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2008 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 I. The Strike Page 5 II. The Unheard Struggles for Control: Intellectual Property Rights, Screen Credit, Workplace Environment, and Differing Standards of Excellence Page 17 III. The Historiography Page 42 Afterword Page 56 Bibliography Page 62 2 Introduction On May 28 th , 1941, seventeen artists were escorted out of the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. -

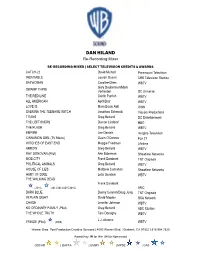

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS CATCH-22 David Michod Paramount Television INSATIABLE Lauren Gussis CBS Television Studios BATWOMAN Caroline Dries WBTV Gary Dauberman/Mark SWAMP THING Verheiden DC Universe THE RED LINE Cairlin Parrish WBTV ALL AMERICAN April Blair WBTV LOVE IS Mara Brock Akil OWN SABRINA THE TEENAGE WITCH Jonathan Schmock Viacom Productions TITANS Greg Berlanti DC Entertainment THE LEFTOVERS Damon Lindelof HBO THE FLASH Greg Berlanti WBTV EMPIRE Lee Daniels Imagine Television CINNAMON GIRL (TV Movie) Gavin O'Connor Fox 21 WITCHES OF EAST END Maggie Friedman Lifetime ARROW Greg Berlanti WBTV RAY DONOVAN (Pilot) Ann Biderman Showtime Networks MOB CITY Frank Darabont TNT Originals POLITICAL ANIMALS Greg Berlanti WBTV HOUSE OF LIES Matthew Carnahan Showtime Networks HART OF DIXIE Leila Gerstein WBTV THE WALKING DEAD Frank Darabont (2010) (2012/2014/2015/2016) AMC DARK BLUE Danny Cannon/Doug Jung TNT Originals IN PLAIN SIGHT David Maples USA Network CHASE Jennifer Johnson WBTV NO ORDINARY FAMILY (Pilot) Greg Berlanti ABC Studios THE WHOLE TRUTH Tom Donaghy WBTV J.J. Abrams FRINGE (Pilot) (2009) WBTV Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.7825 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS LIMELIGHT (Pilot) David Semel, WBTV HUMAN TARGET Jonathan E. Steinberg WBTV EASTWICK Maggie Friedman WBTV V (Pilot) Kenneth Johnson WBTV TERMINATOR: THE SARAH CONNER Josh Friedman CHRONICLES WBTV CAPTAIN -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

Info Fair Resources

………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… Info Fair Resources ………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS 209 East 23 Street, New York, NY 10010-3994 212.592.2100 sva.edu Table of Contents Admissions……………...……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Transfer FAQ…………………………………………………….…………………………………………….. 2 Alumni Affairs and Development………………………….…………………………………………. 4 Notable Alumni………………………….……………………………………………………………………. 7 Career Development………………………….……………………………………………………………. 24 Disability Resources………………………….…………………………………………………………….. 26 Financial Aid…………………………………………………...………………………….…………………… 30 Financial Aid Resources for International Students……………...…………….…………… 32 International Students Office………………………….………………………………………………. 33 Registrar………………………….………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Residence Life………………………….……………………………………………………………………... 37 Student Accounts………………………….…………………………………………………………………. 41 Student Engagement and Leadership………………………….………………………………….. 43 Student Health and Counseling………………………….……………………………………………. 46 SVA Campus Store Coupon……………….……………….…………………………………………….. 48 Undergraduate Admissions 342 East 24th Street, 1st Floor, New York, NY 10010 Tel: 212.592.2100 Email: [email protected] Admissions What We Do SVA Admissions guides prospective students along their path to SVA. Reach out -

Achieving "The Franchise": the Comcast-Nbc Universal Merger and the New Media Marketplace

ACHIEVING "THE FRANCHISE": THE COMCAST-NBC UNIVERSAL MERGER AND THE NEW MEDIA MARKETPLACE Thomas Curtint I. INTRODUCTION In 1997, then-Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission ("FCC" or "Commission") Reed Hundt delivered a speech to the leaders of the cable industry in which he described the future of cable television in terms of what he called "the Franchise."' According to Hundt, this model "consists of the core package of the most popular TV channels and the most popular way to deliver them." Hundt acknowledged that the cable industry "has made huge inroads on the delivery side," and classified broadcast television as "the other side of the Franchise." 2 The Chairman further forecasted that "the core pro- gramming package may or may not be possessed by local broadcasters in the future."' Nearly thirteen years after Chairman Hundt foretold an all-in-one entertain- ment content and delivery service, the Comcast Corporation ("Comcast") is on its way to realizing this vision of "the Franchise," as the media delivery giant undertakes efforts to merge with NBC Universal.' If successful, the merger would give the nation's largest cable corporation control over NBC Univer- t J.D. Candidate, May 2011. Tom would like to thank his parents, Thomas and Donna Curtin, his brother Frank and his extended family for always encouraging the writing proc- ess. He would also like to thank his friends for their constant support, and the Editors and Associates of COMMLAW CONSPECTUS Volumes 18 and 19 for their valued input and advice. I Reed Hundt, Chairman, Fed. Commc'ns Comm'n, Speech at the National Cable Television Association: Cable, Broadcasting, and The Franchise (Mar. -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation. -

… … Mushi Production

1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … Mushi Production (ancien) † / 1961 – 1973 Tezuka Productions / 1968 – Group TAC † / 1968 – 2010 Satelight / 1995 – GoHands / 2008 – 8-Bit / 2008 – Diomédéa / 2005 – Sunrise / 1971 – Deen / 1975 – Studio Kuma / 1977 – Studio Matrix / 2000 – Studio Dub / 1983 – Studio Takuranke / 1987 – Studio Gazelle / 1993 – Bones / 1998 – Kinema Citrus / 2008 – Lay-Duce / 2013 – Manglobe † / 2002 – 2015 Studio Bridge / 2007 – Bandai Namco Pictures / 2015 – Madhouse / 1972 – Triangle Staff † / 1987 – 2000 Studio Palm / 1999 – A.C.G.T. / 2000 – Nomad / 2003 – Studio Chizu / 2011 – MAPPA / 2011 – Studio Uni / 1972 – Tsuchida Pro † / 1976 – 1986 Studio Hibari / 1979 – Larx Entertainment / 2006 – Project No.9 / 2009 – Lerche / 2011 – Studio Fantasia / 1983 – 2016 Chaos Project / 1995 – Studio Comet / 1986 – Nakamura Production / 1974 – Shaft / 1975 – Studio Live / 1976 – Mushi Production (nouveau) / 1977 – A.P.P.P. / 1984 – Imagin / 1992 – Kyoto Animation / 1985 – Animation Do / 2000 – Ordet / 2007 – Mushi production 1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … 1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … Tatsunoko Production / 1962 – Ashi Production >> Production Reed / 1975 – Studio Plum / 1996/97 (?) – Actas / 1998 – I Move (アイムーヴ) / 2000 – Kaname Prod. -

Vol. 3 Issue 4 July 1998

Vol.Vol. 33 IssueIssue 44 July 1998 Adult Animation Late Nite With and Comics Space Ghost Anime Porn NYC: Underground Girl Comix Yellow Submarine Turns 30 Frank & Ollie on Pinocchio Reviews: Mulan, Bob & Margaret, Annecy, E3 TABLE OF CONTENTS JULY 1998 VOL.3 NO.4 4 Editor’s Notebook Is it all that upsetting? 5 Letters: [email protected] Dig This! SIGGRAPH is coming with a host of eye-opening films. Here’s a sneak peak. 6 ADULT ANIMATION Late Nite With Space Ghost 10 Who is behind this spandex-clad leader of late night? Heather Kenyon investigates with help from Car- toon Network’s Michael Lazzo, Senior Vice President, Programming and Production. The Beatles’Yellow Submarine Turns 30: John Coates and Norman Kauffman Look Back 15 On the 30th anniversary of The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, Karl Cohen speaks with the two key TVC pro- duction figures behind the film. The Creators of The Beatles’Yellow Submarine.Where Are They Now? 21 Yellow Submarine was the start of a new era of animation. Robert R. Hieronimus, Ph.D. tells us where some of the creative staff went after they left Pepperland. The Mainstream Business of Adult Animation 25 Sean Maclennan Murch explains why animated shows targeted toward adults are becoming a more popular approach for some networks. The Anime “Porn” Market 1998 The misunderstood world of anime “porn” in the U.S. market is explored by anime expert Fred Patten. Animation Land:Adults Unwelcome 28 Cedric Littardi relates his experiences as he prepares to stand trial in France for his involvement with Ani- meLand, a magazine focused on animation for adults.