History of the Hebrews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Timeline 6 BC to 70 AD One Clue Often Repeated Is Christ’S Birth Could Not Have Been in the Winter, Near December First Century Revelation 25

CODE 166 CODE 196 CODE 228 CODE 243 CODE 251 CODE 294 CODE 427 CODE 490 CODE 590 CODE 666 CODE 01010 COD E 1260 CODE 1447 CODE 1900 CODE 1975 CODE 2300 CODE 6000 CODE 144000 TIMELINE – 6 BCE to 70 CE by Floyd R. Cox (Revised 12-29-2018) Sources: HERE and HERE (Translation: Copy & paste into: https://www.freetranslation.com/) I did a Google search for “date of Herod’s death” and received 14,300 pages of hits. This is evidence there is lots of interest and considered to be importance. Why is it important? Christ born after Herod’s Death? http://code251.com/ If the generally accepted date for Herod’s death is correct (about March 30, 4 BC) then Jesus could not have been conceived in about December, 5 BC, and born 274 days later, on the Related Topics feast of Trumpets, the fall of 4 BC. In this view, Jesus was not born before Herod died. This suggests we should research earlier years and other clues for the conception and birth British Israelism in 5 or 6 BC. Revisited Born in the Winter? Timeline 6 BC to 70 AD One clue often repeated is Christ’s birth could not have been in the winter, near December First Century Revelation 25. Luke says the shepherds of Bethlehem were watching their sheep at night, and this would not likely be in the winter. However, I checked the weather for Bethlehem this year on and Restoring the First Century Context found the temperature in Bethlehem. It was 56 degrees on December 25, 59 degrees on December 26, and 54 on December 27. -

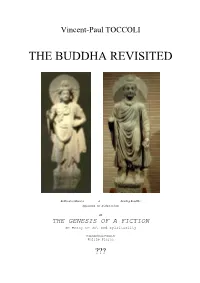

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition

Notes and Errata for Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition Nachum Dershowitz and Edward M. Reingold Cambridge University Press, 2008 4:00am, July 24, 2013 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.) —Walt Whitman: Song of Myself All those complaints that they mutter about. are on account of many places I have corrected. The Creator knows that in most cases I was misled by following. others whom I will spare the embarrassment of mention. But even were I at fault, I do not claim that I reached my ultimate perfection from the outset, nor that I never erred. Just the opposite, I always retract anything the contrary of which becomes clear to me, whether in my writings or my nature. —Maimonides: Letter to his student Joseph ben Yehuda (circa 1190), Iggerot HaRambam, I. Shilat, Maaliyot, Maaleh Adumim, 1987, volume 1, page 295 [in Judeo-Arabic] Cuiusvis hominis est errare; nullius nisi insipientis in errore perseverare. [Any man can make a mistake; only a fool keeps making the same one.] —Attributed to Marcus Tullius Cicero If you find errors not given below or can suggest improvements to the book, please send us the details (email to [email protected] or hard copy to Edward M. Reingold, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 31st Street, Suite 236, Chicago, IL 60616-3729 U.S.A.). If you have occasion to refer to errors below in corresponding with the authors, please refer to the item by page and line numbers in the book, not by item number. -

The Maccabees (Hasmoneans)

The Maccabees Page 1 The Maccabees (Hasmoneans) HASMONEANS hazʹme-nēʹenz [Gk Asamomaios; Heb ḥašmônay]. In the broader sense the term Hasmonean refers to the whole “Maccabean” family. According to Josephus (Ant. xii.6.1 [265]), Mattathias, the first of the family to revolt against Antiochus IV’s demands, was the great-grandson of Hashman. This name may have derived from the Heb ḥašmān, perhaps meaning “fruitfulness,” “wealthy.” Hashman was a priest of the family of Joarib (cf. 1 Macc. 2:1; 1 Ch. 24:7). The narrower sense of the term Hasmonean has reference to the time of Israel’s independence beginning with Simon, Mattathias’s last surviving son, who in 142 B.C. gained independence from the Syrian control, and ending with Simon’s great-grandson Hyrcanus II, who submitted to the Roman general Pompey in 63 B.C. Remnants of the Hasmoneans continued until A.D. 100. I. Revolt of the Maccabees The Hasmonean name does not occur in the books of Maccabees, but appears in Josephus several times (Ant. xi.4.8 [111]; xii.6.1 [265]; xiv.16.4 [490f]; xv.11.4 [403]; xvi.7.1 [187]; xvii.7.3 [162]; xx.8.11 [190]; 10.3 [238]; 10.5 [247, 249]; BJ i.7 [19]; 1.3 [36]; Vita 1 [2, 4]) and once in the Mishnah (Middoth i.6). These references include the whole Maccabean family beginning with Mattathias. In 166 B.C. Mattathias, the aged priest in Modein, refused to obey the order of Antiochus IV’s envoy to sacrifice to the heathen gods, and instead slew the envoy and a Jew who was about to comply. -

July 2020, Volume 19, No

The Barnesville Lantern Barnesville Baptist Church 17917 Barnesville Road/P.O. Box 69 Barnesville, Maryland 20838 301-407-0500 (phone/fax) www.barnesvillebaptist.org [email protected] July 2020, Volume 19, No. 2 Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path (Psalm 119:105). The Pastor’s Spotlight In This Edition: In Bible times, the Egyptian pharaoh was the most powerful The Pastor’s Spotlight, Page 1 man in the world. As portrayed by Yul Brynner in the 1956 Upcoming Events, Page 1 movie The Ten Commandments, Pharaoh’s word was law: The Pew Perspective, Page 2 “So let it be written, so let it be done”! But when the Lord had Biblical Garments Scramble and Word Search, Page 2 Moses tell Pharaoh to “Let my people go”, God overturned July Birthdays, Page 3 Pharaoh’s world until God’s Word was fulfilled. God’s Word Prayer Concerns, Page 3 can create anything or turn any situation around (Genesis 1:1; Business Meeting Briefs, Page 3 John 1:1). He made Israel a free nation when freedom was humanly impossible, just as easily as He called the universe COTCD Cartoon, Page 3 into existence out of nothingness. “God…gives life to the Biblical Garments Scramble Answers, Page 3 dead and calls those things which do not exist as though they News You Can Use, Page 4 did” (Romans 4:17). So as we go through this evil world, we July 2020 Calendar, Page 5 need to focus on God’s Word and better understand that God’s Holy Word is alive and has the power to move and Upcoming Events pierce our own hearts as well as change the entire world. -

Persian Royal Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY PERSIAN ROYAL ANCESTRY Achaemenid Dynasty from Greek mythical Perses, (705-550 BC) یشنماخه یهاشنهاش (Achaemenid Empire, (550-329 BC نايناساس (Sassanid Empire (224-c. 670 INTRODUCTION Persia, of which a large part was called Iran since 1935, has a well recorded history of our early royal ancestry. Two eras covered are here in two parts; the Achaemenid and Sassanian Empires, the first and last of the Pre-Islamic Persian dynasties. This ancestry begins with a connection of the Persian kings to the Greek mythology according to Plato. I have included these kind of connections between myth and history, the reader may decide if and where such a connection really takes place. Plato 428/427 BC – 348/347 BC), was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. King or Shah Cyrus the Great established the first dynasty of Persia about 550 BC. A special list, “Byzantine Emperors” is inserted (at page 27) after the first part showing the lineage from early Egyptian rulers to Cyrus the Great and to the last king of that dynasty, Artaxerxes II, whose daughter Rodogune became a Queen of Armenia. Their descendants tie into our lineage listed in my books about our lineage from our Byzantine, Russia and Poland. The second begins with King Ardashir I, the 59th great grandfather, reigned during 226-241 and ens with the last one, King Yazdagird III, the 43rd great grandfather, reigned during 632 – 651. He married Maria, a Byzantine Princess, which ties into our Byzantine Ancestry. -

200 Bc - Ad 400)

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 171-191 P. ARNAUD 171 BEIRUT: COMMERCE AND TRADE (200 BC - AD 400) PASCAL ARNAUD We know little of Beirut's commerce and trade, and shall probably continue to know little about this matter, despite a lecture given by Mrs Nada Kellas in 19961. In fact, the history of Commerce and Trade relies mainly on both ar- chaeological and epigraphical evidence. As far as archaeological evidence is concerned, one must remember that only artefacts strongly linked with ceram- ics, i.e. vases themselves and any items, carried in amphoras, (predominantly, but not solely, liquids, can give information about the geographical origin, date and nature of such products. The huge quantities of materials brought to the light by recent excavations in Beirut should, one day, provide us with new evi- dence about importations of such products in Beirut, but we will await the complete study of this material, which, until today by no means provided glo- bal statistics valid at the whole town scale. The evidence already published still allows nothing more than mere subjective impressions about the origins of the material. I shall try nevertheless to rely on such impressions about that ma- terial, given that we lack statistics, and that it is impossible to infer from any isolated sherd the existence of permanent trade-routes and commercial flows. The results of such an inquiry would be, at present, worth little if not con- fronted with other evidence. On the other hand, it should be of great interest to identify specific Berytan productions among the finds from other sites in order to map the diffusion area of items produced in Beirut and the surrounding territory. -

Hugh Lindsay, Strabo and the Shape of His Historika Hypomnemata

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME TWENTY-EIGHT: 2014 NUMBERS 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson David Hollander Timothy Howe Joseph Roisman John Vanderspoel Pat Wheatley Sabine Müller ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 28 (2014) Numbers 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Carol Thomas, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume twenty-eight Numbers 1-2 1 Hugh Lindsay, Strabo and the shape of his Historika Hypomnemata 20 Paul McKechnie, W.W. Tarn and the philosophers 37 Monica D’Agostini, The Shade of Andromache: Laodike of Sardis between Homer and Polybios 61 John Shannahan, Two Notes on the Battle of Cunaxa NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Leuven), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Carol Thomas (University of Washington), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel and Pat Wheatley. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

High Priests Garments and History

THE HIGH PRIEST - GARMENTS AND HISTORY Historical Significance and Symbolism Joseph Martinez Manassas Chapter #81, RAM THE HIGH PRIEST • Brief Introduction • Appearance in the VSL • Garments – Biblical Explanations – Use in Royal Arch • Observations Joseph Martinez Manassas Chapter #81, RAM TRIVIA • Master of the Chapter – in United States – Excellent High Priest, King, and Scribe • In United Kingdom – First, Second, Third Principal • In Ireland – Excellent King, High Priest and Chief Scribe Joseph Martinez Manassas Chapter #81, RAM TRIVIA • In United Kingdom – First, Second, Third Principal – Most Excellent Zerubbabel Joseph Martinez Manassas Chapter #81, RAM THE HIGH PRIEST • Master of a Chapter • Member of the Grand Council • Past High Priest – Wears a distinctive Symbol Joseph Martinez Manassas Chapter #81, RAM ROYAL ARCH - HIGH PRIEST SYMBOL • Is the Breastplate of the High Priest of Israel • Described in Exodus 28 • Created in Exodus 39 • Worn by Aaron in Leviticus 8 Joseph Martinez Manassas Chapter #81, RAM THE HIGH PRIEST OF ISRAEL • Aaron was the first – Exodus 28 • Was to be successive through Aaron’s line – Aaron Eleazar Phinehas Abishua Bukki Uzzi – Ithamar Eli Ahitub Ahijah Ahimelech Abiathar • Solomon – Abiathar Zadok (High Priest at completion of the First Temple) Joseph Martinez Manassas Chapter #81, RAM THE FIRST TEMPLE • David – Abiathar and Zadok were High Priests in tandem • Solomon – When Adonijah tries to claim power and kingship • Abiathar sides with Adonijah’s camp – David near death proclaims Solomon -

"New Bible Translations," Scripture 4 No. 4

102 SCRIPTURE difficulties of publication will not long delay the greatly desired works. Back numbers of SCRIPTURE. Complete sets are still a comprehensive price of 15 s. 6d. (1946 to date). Single copies each. Please apply to the Treasurer, 43 Palace Street, London It is now possible to subscribe to SCRIPTURE (6s. 6d. per: without becoming a member of the C.B.A. This facility use especially to overseas subscribers. BOOKS AND PERIODICALS RECEIVED . We acknowledge with thanks the following: Cultllra Biblica, Catholic Biblical Quarterly, Collationes Brugenses, Pax, Verbum Domini, Reunion. From Burns Oates and Washbourne: Knox translation The Gospel according to St. Matthew, The Gospel St. Mark, The Gospel according to St. Luke, The Gospel according Separately in paper covers. The Old Testament, Vo!. n. Palanque &c., The Church in the Christian Roman Empire, Vol. I. F. R. Hoare, The Gospel according to St. John. From the Catholic University of America: Heidt, Angelology of the Old Testament. From T. Nelson and Sons, Edinburgh: Harrison, The Bible in Britain. From Letouzey and Ane, Paris: Pirot-Clamer, La Sainte Bible, Tome IV (Par.-'-Job). NEW BIBLE TRANSLATIONS! HE June number of Theology contains an informing attiC: Dr. Hendry of Princeton Theological Seminary on t T translations of the Bible that are being prepared in Engla.' the United States. Each of the two versions is to be a new trans not a revision of any existing version; it will avoid all archaie and phrases (" the second person singular shall be employed q prayer "); it is to be based on what scholars consider to be th available texts, which for the Hebrew Old Testament means ... -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th.