Mark Adamo: the Solo Vocal Works Through 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lusty Little Women: the Secret Desires of the March Sisters

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Lusty Little Women: The Secret Desires of the March Sisters The adventures of the March sisters are about to go into untapped realms... Introducing Lusty Little Women, a scintillating twist on Louisa May Alcott’s classic that infuses the original text with sexy new scenes that will surprise, arouse, and delight. Jo, Meg, Beth, and Amy are coming of age, and exhilarat- ing temptations await them around every corner. The handsome young neighbor, attentive doctor, and mysterious foreigner intro- duce the little women to the passion-filled world of desire, plea- sure, and satisfaction. Retold as a risque romance, this book follows the slightly older and much more adventurous sisters—and they’re all ready to plumb the depths of their previously constrained courtships. Will these steamy encounters fulfill their deepest yearnings? Have they found true love or been blinded by lust? “Rereading the Little Women series as an adult was a wonderful experience, reuniting me with characters I consider old friends,” explains author Margaret Pearl. “But as I read, the flirtations and attraction between the young women and their suitors left me imagining how Alcott may have written it if she were able to show what went on behind the curtain—and between the sheets!. Lusty Little Women is the result of a love of the characters and an ir- repressible desire to see them get the pleasure they truly deserve.” Complete with romantic, racy, and naughty scenarios fans $14.95, Trade Paper June 2014 from Ulysses Press have always fantasized about, Lusty Little Women will thrill both ISBN: 978-1-61243-302-8 well-versed and new readers of the classic novel. -

Schubert's Mature Operas: an Analytical Study

Durham E-Theses Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study Bruce, Richard Douglas How to cite: Bruce, Richard Douglas (2003) Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4050/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Richard Douglas Bruce Submitted for the Degree of PhD October 2003 University of Durham Department of Music A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without their prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. 2 3 JUN 2004 Richard Bruce - Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Submitted for the degree of Ph.D (2003) (Abstract) This thesis examines four of Franz Schubert's complete operas: Die Zwillingsbruder D.647, Alfonso und Estrella D.732, Die Verschworenen D.787, and Fierrabras D.796. -

Little-Women-Playbill.Pdf

Director’s Note Greetings and welcome to this year’s musical: “Little Women.” When I was asked “What musical are you doing this fall?” and responded with Little Women, most everyone said “Oh, I didn’t know there was a musical version.” Which isn’t too surprising, but I am glad you are here to enjoy it. Louisa May Alcott’s stories and the wonderful music of Mr. Howard are brought to life by the talented crew, costuming, tech, pit orchestra, actors, and actresses. Every single student is important to how successful this production has been, and to the family that is MV theatre. We always have an amazing team here in the theatre program. Lexi Runnals has been an amazing teammate to work with. She and I compliment each other’s strength’s well, creating one dynamic duo! Mikayla Meyer has taken on a bigger role this year, and we made a few changes to how things are run. The crew responded well, and has done an amazing job with everything. We were also fortunate to have the help of an MV alumni, in Jack Caughey. Jack was very involved in the theatre program during his time at Mounds View, and has been giving back by helping out with our technical team. And, of course, it wouldn’t be a musical without the pit orchestra, and Mr. Richardson has done it again, contributing a great sound that only makes the show more impressive. Where would MV Theatre be without BRAVO! I can’t thank them enough for all the time they spend volunteering for these productions, as well as their contributions to the program (such as a new table saw purchased for the crew this year!). -

Hearing Nostalgia in the Twilight Zone

JPTV 6 (1) pp. 59–80 Intellect Limited 2018 Journal of Popular Television Volume 6 Number 1 © 2018 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jptv.6.1.59_1 Reba A. Wissner Montclair State University No time like the past: Hearing nostalgia in The Twilight Zone Abstract Keywords One of Rod Serling’s favourite topics of exploration in The Twilight Zone (1959–64) Twilight Zone is nostalgia, which pervaded many of the episodes of the series. Although Serling Rod Serling himself often looked back upon the past wishing to regain it, he did, however, under- nostalgia stand that we often see things looking back that were not there and that the past is CBS often idealized. Like Serling, many ageing characters in The Twilight Zone often sentimentality look back or travel to the past to reclaim what they had lost. While this is a perva- stock music sive theme in the plots, in these episodes the music which accompanies the scores depict the reality of the past, showing that it is not as wonderful as the charac- ter imagined. Often, music from these various situations is reused within the same context, allowing for a stock music collection of music of nostalgia from the series. This article discusses the music of nostalgia in The Twilight Zone and the ways in which the music depicts the reality of the harshness of the past. By feeding into their own longing for the reclamation of the past, the writers and composers of these episodes remind us that what we remember is not always what was there. -

Little Women Synopsis

LITTLE WOMEN, A LITTLE MUSICAL SYNOPSIS - ACT I PROLOGUE—Attic of the March home. SCENE 1—New England Village in winter. Cast enters—coming and going on a busy village street (JOYOUS DAY). The March girls are taking dinner to the Hummels. Marmee stops to post a letter (MY LITTLE WOMEN). SCENE 2—March home. March girls are bemoaning Christmas with no money. Marmee comes home with a letter from Father. Suddenly, Aunt March blusters in, bringing one dollar for each of them. They hurry off to the shops to spend it. Marmee reads Father’s letter. They sing together±—he away at war, and she at home (JOYOUS DAY REPRISE 1/MY PRAYER). SCENE 3—Willoughby's store. The March girls are buying presents for themselves. Beth decides to get something for Marmee instead. The rest follow (JOYOUS DAY REPRISE 2). SCENE 4—March home. The girls speculate about "that Laurence boy" next door. Jo's dress catches fire. They receive an invitation (TO THE BALL). SCENE 5—Laurence Mansion. Party guests arrive (TO THE BALL REPRISE). Guests move to the ballroom (THE PALACE BEAUTIFUL), leaving Laurie and Jo alone in the antechamber. They meet and dance the polka together (JO & LAURIE'S POLKA). Meg reenters with a sprained ankle. Mr. Brook dotes on her and offers to take her home. Jo and Laurie sing about love (LOVE DOESN'T HAPPEN THAT WAY). SCENE 6— Laurence Mansion. Jo visits the "ailing Mr. Laurence." Jo sings about her dreams (I WILL FLY). Old Mr. Laurence introduced. SCENE 7—March home. -

APR 9, 2017 LYRICS by MINDI DICKSTEIN | DIRECTED by VALERIE JOYCE About Villanova University

VILLANOVA THEATRE PRESENTS BOOK BY ALLAN KNEE | MUSIC BY JASON HOWLAND MAR 28 - APR 9, 2017 LYRICS BY MINDI DICKSTEIN | DIRECTED BY VALERIE JOYCE About Villanova University Since 1842, Villanova University’s Augustinian Catholic intellectual tradition has been the cornerstone of an academic community in which students learn to think critically, act compassionately and succeed while serving others. There are more than 10,000 undergraduate, graduate and law students in the University’s six colleges – the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the Villanova School of Business, the College of Engineering, the College of Nursing, the College of Professional Studies and the Villanova University School of Law. As students grow intellectually, Villanova prepares them to become ethical leaders who create positive change everywhere life takes them. In Gratitude The faculty, staff, and students of Villanova Theatre extend sincere gratitude to those generous benefactors who have established endowed funds in support of our efforts: Marianne M. and Charles P. Connolly, Jr. ’70 Dorothy Ann and Bernard A. Coyne, Ph.D. ̓55 Patricia M. ’78 and Joseph C. Franzetti ’78 The Donald R. Kurz Family Peter J. Lavezzoli ’60 Msgr. Joseph F. X. McCahon ’65 Mary Anne C. Morgan ̓70 and Join Villanova Theatre online! Family & Friends of Brian G. Morgan ̓67, ̓70 Anthony T. Ponturo ’74 Follow Villanova Follow Villanova Like Villanova Theatre on Twitter Theatre on Twitter For information about how you can support the Theatre Theatre on Facebook! @VillanovaTheatr @VillanovaTheatre Department, please contact Heather Potts-Brown, Director of Annual Giving, at (610) 519-4583. Find VillanovaTheatre on Tumblr Villanova Theatre gratefully acknowledges the generous support of its many patrons & subscribers. -

PRESENTS Table of Contents

PRESENTS Table of Contents Welcome................................................................................................................. 3 Staff and Board of Directors..........................................................................6 About Pittsburgh Festival Opera.................................................................7 Cornetti’s Candid Concert and After-Party | July 10................................8 Marianne: Unstaged | July 11, 18, and 25.................................................10 Pit Crew: Singer-Free Sundays | July 12, 19, and 26..............................13 Leitmotif: Walking through Wagner | July 16..........................................17 I, Too, Sing | July 17...........................................................................................18 Composer Spotlight: Mark Adamo | July 23.............................................20 Putting it Together: Online Young Artists Program | July 24..........21 2020 OYAP Faculty........................................................................................... 26 Rusalka: A Mermaid’s Tale | July 25............................................................27 Contributions, Gifts, and Institutional Support................................. 29 Welcome from the President We need 20-20 vision to view the events of 2020. Much of what we took for granted, including the highest ever level of our economy and the lowest ever level of unemployment, suggested a bright future for the performing arts. We at Pittsburgh Festival Opera were especially -

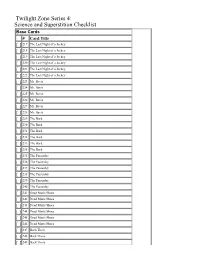

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

FY19 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2018–19 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 6 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 20 Our Patrons On the cover: Yannick Nézet-Séguin takes a bow after his first official performance as Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director PHOTO: JONATHAN TICHLER / MET OPERA 2 Introduction The 2018–19 season was a historic one for the Metropolitan Opera. Not only did the company present more than 200 exiting performances, but we also welcomed Yannick Nézet-Séguin as the Met’s new Jeanette Lerman- Neubauer Music Director. Maestro Nézet-Séguin is only the third conductor to hold the title of Music Director since the company’s founding in 1883. I am also happy to report that the 2018–19 season marked the fifth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so, as we recorded a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Saint-Saëns’s epic Samson et Dalila and also included three other new productions, as well as three exhilarating full cycles of Wagner’s Ring and a full slate of 18 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 13th season, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office, media, and presentations) totaled $121 million. As in past seasons, total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. The new productions in the 2018–19 season were the work of three distinguished directors, two having had previous successes at the Met and one making his company debut. -

Proquest Dissertations

The use of the glissando in piano solo and concerto compositions from Domenico Scarlatti to George Crumb Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Lin, Shuennchin Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 08:04:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288715 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fihns the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fice, whfle others may be from any type of computer primer. The qaality^ of this rqirodnctioii is dependent upon the quality of the copy sabmitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and hnproper alignmem can adverse^ affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., nu^s, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing fi'om left to right m equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Press Release Central City Opera Announces Casting

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CONTACT: Valerie Hamlin, PR/Communications Director Dec. 11, 2006 303-292-6500, ext. 108; [email protected] CENTRAL CITY OPERA ANNOUNCES CASTING FOR 75TH ANNIVERSARY 2007 FESTIVAL LA TRAVIATA /POET LI BAI-World Premiere/ CINDERELLA/THE SAINT OF BLEECKER STREET 2007 Festival Features Four Operas with World Renowned Artists *=Central City Opera Debut Denver, Colo.— The artists have been selected for Central City Opera’s (CCO) historic 2007 75th Anniversary Festival. This monumental year is celebrated with the world premiere of Chinese opera, Poet Li Bai, presented in partnership with the Asian Performing Arts of Colorado as a special offering with only six performances. The company’s regular 2007 festival season features three new productions, including Verdi’s La Traviata, Massenet’s Cinderella and Menotti’s The Saint of Bleecker Street. Four operas will be presented in one festival for the first time in the history of Central City Opera during the 2007 Festival, which runs June 30 through Aug. 19 at the Central City Opera House in Central City, CO. “As we celebrate a landmark anniversary for Central City Opera, we are proud to showcase some of the best artists from around the globe,” states General/Artistic Director Pelham G. Pearce. “The high caliber of singers, designers and directors we have contracted for 2007 is a testament to how far this company has come in its 75 years and to the direction we are going in the future.” La Traviata (June 30 – Aug. 12) – The 2007 Festival opens with Verdi’s popular Italian opera about a young courtesan stricken with consumption and her tumultuous love affair with a nobleman in Paris. -

The Choral Cycle

THE CHORAL CYCLE: A CONDUCTOR‟S GUIDE TO FOUR REPRESENTATIVE WORKS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY RUSSELL THORNGATE DISSERTATION ADVISORS: DR. LINDA POHLY AND DR. ANDREW CROW BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2011 Contents Permissions ……………………………………………………………………… v Introduction What Is a Choral Cycle? .............................................................................1 Statement of Purpose and Need for the Study ............................................4 Definition of Terms and Methodology .......................................................6 Chapter 1: Choral Cycles in Historical Context The Emergence of the Choral Cycle .......................................................... 8 Early Predecessors of the Choral Cycle ....................................................11 Romantic-Era Song Cycles ..................................................................... 15 Choral-like Genres: Vocal Chamber Music ..............................................17 Sacred Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era ................................20 Secular Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era .............................. 22 The Choral Cycle in the Twentieth Century ............................................ 25 Early Twentieth-Century American Cycles ............................................. 25 Twentieth-Century European Cycles ....................................................... 27 Later Twentieth-Century American