The Significance of Hindu Temple Architecture in the Pantomime Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting an Architectural Past Ram Raz and the Treatise in South Asia Author(S): Madhuri Desai Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol

Interpreting an Architectural Past Ram Raz and the Treatise in South Asia Author(s): Madhuri Desai Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 71, No. 4, Special Issue on Architectural Representations 2 (December 2012), pp. 462-487 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jsah.2012.71.4.462 Accessed: 02-07-2016 12:13 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians This content downloaded from 160.39.4.185 on Sat, 02 Jul 2016 12:13:51 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Figure 1 The relative proportions of parts of columns (from Ram Raz, Essay on the Architecture of the Hindus [London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1834], plate IV) This content downloaded from 160.39.4.185 on Sat, 02 Jul 2016 12:13:51 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Interpreting an Architectural Past Ram Raz and the Treatise in South Asia madhuri desai The Pennsylvania State University he process of modern knowledge-making in late the design and ornamentation of buildings (particularly eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century South Hindu temples), was an intellectual exercise rooted in the Asia was closely connected to the experience of subcontinent’s unadulterated “classical,” and more signifi- T 1 British colonialism. -

Common Elements of Dravidian Temple Architecture–A Study

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347–4564; ISSN (E): 2321–8878 Vol. 7, Issue 2, Feb 2019, 583–588 © Impact Journals COMMON ELEMENTS OF DRAVIDIAN TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE–A STUDY D. Gandhimathi & K. Arul Mary Research Scholar, Department of History, PSGR Krishnammal College for Women, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India Research Scholar, Department of History, PSGR Krishnammal College for Women, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India Received: 17 Feb 2019 Accepted: 21 Feb2019 Published: 28 Feb 2019 ABSTRACT The South Indian temple architecture is known as Dravidian architecture. The South Indian temple has many architectural features. This article will explain the common elements of the Shivan temples in Tamilnadu. KEYWORDS: South Indian Temple, Dravidian Architecture, Architecture, Kongu Region INTRODUCTION Hindu temple architecture as the fundamental type of Hindu architecture has numerous assortments of style, however the fundamental idea of the Hindu sanctuary continues as before, with the basic element an internal sanctum, the garbha griha or belly chamber, where the essential Murti or the picture of a god is housed in a straightforward uncovered cell. On the outside, the garbhagriha is delegated by a pinnacle like shikhara, additionally called the vimana in the south. The place of worship assembling frequently incorporates a walking for parikrama (circumambulation), a mandapa gathering lobby, and at times an antarala waiting room and yard among garbhagriha and mandapa. There may promote mandapas or different structures, associated or disconnected, in enormous sanctuaries, together with other little sanctuaries in the compound. These terminologies are common across all temples built in Dravidian architecture and not specific to Shiva temples in Tamil Nadu. -

The Evolution of the Temple Plan in Karnataka with Respect to Contemporaneous Religious and Political Factors

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 7, Ver. 1 (July. 2017) PP 44-53 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Evolution of the Temple Plan in Karnataka with respect to Contemporaneous Religious and Political Factors Shilpa Sharma 1, Shireesh Deshpande 2 1(Associate Professor, IES College of Architecture, Mumbai University, India) 2(Professor Emeritus, RTMNU University, Nagpur, India) Abstract : This study explores the evolution of the plan of the Hindu temples in Karnatak, from a single-celled shrine in the 6th century to an elaborate walled complex in the 16th. In addition to the physical factors of the material and method of construction used, the changes in the temple architecture were closely linked to contemporary religious beliefs, rituals of worship and the patronage extended by the ruling dynasties. This paper examines the correspondence between these factors and the changes in the temple plan. Keywords: Hindu temples, Karnataka, evolution, temple plan, contemporary beliefs, religious, political I. INTRODUCTION 1. Background The purpose of the Hindu temple is shown by its form. (Kramrisch, 1996, p. vii) The architecture of any region is born out of various factors, both tangible and intangible. The tangible factors can be studied through the material used and the methods of construction used. The other factors which contribute to the temple architecture are the ways in which people perceive it and use it, to fulfil the contemporary prescribed rituals of worship. The religious purpose of temples has been discussed by several authors. Geva [1] explains that a temple is the place which represents the meeting of the divine and earthly realms. -

1.1.3-Hss455

MANGALORE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY MA History Course No. HSS: 455 (Soft Core) ART AND ARCHITECTURE OF KARNATAKA TO AD 14TH CENTURY Learning objective: This paper’s main aim is to know the evolution of art and architecture in Karnataka and also to know more about the development of historical writings on Karnataka art and architecture. Learning outcome; After the course the students will come to know about the beginning of historical writings on art and architecture, various sources for the study of art and architecture and finally evolutions of art and architecture in Karnataka. I. Historiography and sources: James Fergusson, Percy Brown, Henry Cousens, Alexander Rea- Later works. Manasara, Inscriptions and monuments- the Nagara, Vesara and Dravida traditions. II. Pre-historic art and architecture: Rock paintings- megalithic structures-types- Pre-Badami Chalukya art and architecture: Sites connected with the Maurya and the Satavahana period art- The Kadambas- important monuments- main features, monuments of the Gangas of Talakad- sculptures, pillars. Role of ideology, religious groups. III. Badami Chalukya art and architecture- the cave temples-characteristic features, the experiments at Pattadakal, important sites of structural temples, main features, cave paintings. Rashtrakuta art and architecture; different types of temples-sites of rock-cut architecture, main features, structural temples, important sites. IV. The Chalukyas of Kalyan and the Hoysalas of Dorasamudra-places connected with the Chalukya monuments- -characteristic features, places connected with the Hoysala temple- Main features- differences and similarities between the two styles of architecture. SELECT READING LIST: 1. Acharya, P.K. Indian Architecture According to Manasara, (Oxford, 1921) 2. ______. Architecture of Manasara, (Oxford, 1933) 3. -

The South Indian Hindu Temple Building Design System on the Architecture of the Silpa Sastra and the Dravida Style

The South Indian Hindu temple building design system On the architecture of the Silpa Sastra and the Dravida style K. J. Oijevaar b1090127 September 2007 Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands [email protected] Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Vastupurusa ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Orientation - The gnomon .............................................................................................................. 8 Zoning in the temple – Using the grid ........................................................................................ 10 Defining the groundplan ................................................................................................................ 12 Going vertical - The temple as a house for the Gods ............................................................... 15 The Hindu order ............................................................................................................................. 18 Upapítha or pedestal .................................................................................................................. 19 Athisthána or base ...................................................................................................................... 21 Sthamba or pillar and the thickness of walls ......................................................................... -

Study of Indian Hindu Temple Architecture and Art of Two Shaiva Temples of Eastern Odisha Pjaee, 17(1) (2020)

STUDY OF INDIAN HINDU TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE AND ART OF TWO SHAIVA TEMPLES OF EASTERN ODISHA PJAEE, 17(1) (2020) STUDY OF INDIAN HINDU TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE AND ART OF TWO SHAIVA TEMPLES OF EASTERN ODISHA Dr. Ratnakar Mohapatra Assistant Professor, Department of History, KISS, Deemed to be University, Bhubaneswar, PIN-751024, Odisha, India. Dr. Ratnakar Mohapatra , Study Of Indian Hindu Temple Architecture And Art Of Two Shaiva Temples Of Eastern Odisha , Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(1). ISSN 1567-214x. Keywords: Hindu, temple, architecture, Shaiva , monument, Eastern, Odisha, India. Abstract: The building plans of the Shaiva temples of the Eastern Odisha are significant part of the Hindu temple engineering of India. The surviving temples of the Eastern piece of Odisha address the Kalinga style of temple engineering of India. Indeed, the structural highlights of the two Shaiva temples of the Eastern Odisha draw the consideration of craftsmanship antiquarians and archeologists to embrace research works. The two Shaiva temples of the Eastern Odisha, which are taken here for conversation, are like 1. Isvaranatha temple of Jiunti, 2. Gangamani temple of Gangesvaragarh. The current temple of Isvaranatha of Jiunti is totally a revamped temple of that region. In some cases, this temple is likewise said by the neighborhood individuals as Isvaradeva rather than Isvaranatha. It addresses one of the great examples of the block landmarks in the Eastern Odisha. This temple is momentous by its exquisite and smooth highlights. Albeit the temple of Gangamani of Gangesvaragarh is little in size still it is a memory of the Ganga landmark of middle age Odisha. -

PILGRIM CENTRES of INDIA (This Is the Edited Reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the Same Theme Published in February 1974)

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA A DISTINCTIVE CULTURAL MAGAZINE OF INDIA (A Half-Yearly Publication) Vol.38 No.2, 76th Issue Founder-Editor : MANANEEYA EKNATHJI RANADE Editor : P.PARAMESWARAN PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA (This is the edited reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the same theme published in February 1974) EDITORIAL OFFICE : Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan Trust, 5, Singarachari Street, Triplicane, Chennai - 600 005. The Vivekananda Kendra Patrika is a half- Phone : (044) 28440042 E-mail : [email protected] yearly cultural magazine of Vivekananda Web : www.vkendra.org Kendra Prakashan Trust. It is an official organ SUBSCRIPTION RATES : of Vivekananda Kendra, an all-India service mission with “service to humanity” as its sole Single Copy : Rs.125/- motto. This publication is based on the same Annual : Rs.250/- non-profit spirit, and proceeds from its sales For 3 Years : Rs.600/- are wholly used towards the Kendra’s Life (10 Years) : Rs.2000/- charitable objectives. (Plus Rs.50/- for Outstation Cheques) FOREIGN SUBSCRIPTION: Annual : $60 US DOLLAR Life (10 Years) : $600 US DOLLAR VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements 1 2. Editorial 3 3. The Temple on the Rock at the Land’s End 6 4. Shore Temple at the Land’s Tip 8 5. Suchindram 11 6. Rameswaram 13 7. The Hill of the Holy Beacon 16 8. Chidambaram Compiled by B.Radhakrishna Rao 19 9. Brihadishwara Temple at Tanjore B.Radhakrishna Rao 21 10. The Sri Aurobindo Ashram at Pondicherry Prof. Manoj Das 24 11. Kaveri 30 12. Madurai-The Temple that Houses the Mother 32 13. -

A Review Study on Architecture of Hindu Temple ______Prathamesh Gurme1,Prof

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT IN Volume-8,Issue-4,(Oct-17) TECHNOLOGY ISSN (O) :- 2349-3585 A REVIEW STUDY ON ARCHITECTURE OF HINDU TEMPLE __________________________________________________________________________________________ PRATHAMESH GURME1,PROF. UDAY PATIL2 1UG SCHOLAR,2HEAD OF DEPARTMENT, DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL ENGINEERINGBHARATI VIDHYAPEETH'S COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING , LAVALE , PUNE , INDIA ABSTRACT : Hinduism is the predominant religion of the and even the traditional arts make their appearances in Indian subcontinent. Dating back to the Iron Age , it is often many sculptures of Hindu origin. Sculpture is inextricably called the oldest living religion in the world. Hinduism has linked with architecture in Hindu temples, which are usually no single founder and is a conglomeration of diverse devoted to a number of different deities. The Hindu temple traditions and philosophies rather than a rigid set of beliefs. style reflects a synthesis of arts, the ideals of dharma , Most Hindus believe in a single supreme God who appears beliefs, values , and the way of life cherished under in many different manifestations as devas (celestial beings or Hinduism. Elaborately ornamented with sculpture deities), and they may worship specific devas as individual throughout, these temples are a network of art, pillars with facets of the same God. Hindu art reflects this plurality of carvings, and statues that display and celebrate the four beliefs, and Hindu temples, in which architecture and important and necessary principles of human life under sculpture are inextricably connected, are usually devoted to Hinduism—the pursuit of artha (prosperity, wealth), the different deities. Deities commonly worshiped include Shiva pursuit of kama (pleasure, sex), the pursuit of dharma the Destroyer; Vishnu in his incarnations as Rama and (virtues, ethical life), and the pursuit of moksha (release, Krishna; Ganesha, the elephant god of prosperity; and self-knowledge). -

Temples of India

TEMPLES OF INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOCRAPHY SUBMITTED !N PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iHagter of librarp Science 1989-90 BY ^SIF FAREED SIDDIQUI Roll. No. 11 Enrolment. No. T - 8811 Under the Supervision of MR. S. MUSTAFA K. Q. ZAIDI Lecturer DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIIVi UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1990 /> DS2387 CHECKED-2002 Tel t 29039 DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE AUGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202001 (India) September 9, 1990 This is to certify that the PI* Lib* Science dissertation of ^r* Asif Fareed Siddiqui on ** Temples of India t A select annotated bibliography " was compiled under my supervision and guidance* ( S. nustafa KQ Zaidi ) LECTURER Dedicated to my Loving Parents Who have always been a source of Inspiration to me CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENT i - ii LISTS OF PERIODICALS iii - v PART-I INTRODUCTION 1-44 PART-II ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY 45 - 214 PART-III INDEX 215 - 256 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. S.Mustafa K.Q. Zaidi, Lecturer, Department of Library Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh who inspite of his many pre-occupation spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step during the course of this study. His deep and critical understanding of the problem helped me a lot in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to Professor Mohd. Sabir Husain, Chairman, Department of Library Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for his able guidance and suggestions whenever needed. I am also highly indebted to Mr. Almuzaffar Khan,Reader, Department of Library Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh whose invaluable guidance and suggestions were always available to me. -

Ofutopiasfinalnewvrindaban

Caila Drew-Morin June 1, 2017 The Palace of Gold On the top of a hill that is on one side overlooking the Appalachian hills and valleys and on the other the Americanized Hindu community, the Palace of Gold at New Vrindaban West Virginia is an impressive product of American interpretations of Hinduism.1 The community, started by Keith Gordon Ham who was to become known by his Hindu name, Kirtanananda, was an effort to make Hinduism accessible to Americans. Moving towards this goal Kirtanananda relied extensively upon his teacher, Abhay Charanaravinda Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada a man of seventy years old by the time he first came from India to America to spread Hinduism.2 In addition to teaching Prabhupada created an international Hindu network to connect Hindu projects all over the world. As part of these goals of spreading Hinduism Prabhupada encouraged the first North American Hindu community to be created and so New Vrindaban was born. Not only in how the devotees chose to interpret and practice Hinduism, valuing some parts of the religion more than others, but also the ideological differences of these American Hindus versus traditional Indian Hindus are displayed in the architecture at New Vrindaban. The main temple room of the Palace of Gold can be seen in figure 1 and will work as a jumping off point for the analysis of how Americanized Hindu architecture contrasts with Hindu temples India both in terms of materials present as well as how these materials are utilized in construction. 1 "Attractions," America's Taj Mahal Palace of Gold, last modified 2013, accessed May 29, 2017, http://www.palaceofgold.com/attractions.html. -

Chapter 6 Temple Architecture

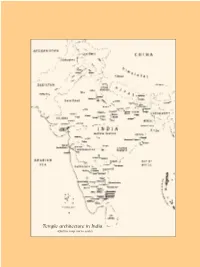

Temple architecture in India (Outline map not to scale) 6 TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURE OST of the art and architectural remains that survive Today when we say 'temple' Mfrom Ancient and Medieval India are religious in in English we generally nature. That does not mean that people did not have art in mean a devalaya, devkula their homes at those times, but domestic dwellings and mandir, kovil, deol, the things in them were mostly made from materials like devasthanam or prasada wood and clay which have perished, or were made of metal depending on which part of India we are in. (like iron, bronze, silver and even gold) which was melted down and reused from time to time. This chapter introduces us to many types of temples from India. Although we have focussed mostly on Hindu temples, at the end of the chapter you will find some information on major Buddhist and Jain temples too. However, at all times, we must keep in mind that religious shrines were also made for many local cults in villages and forest areas, but again, not being of stone the ancient or medieval shrines in those areas have also vanished. Kandariya Mahadeo temple, Khajuraho THE BASIC FORM OF THE HINDU TEMPLE The basic form of the Hindu temple comprises the following: (i) a cave-like sanctum (garbhagriha literally ‘womb-house’), which, in the early temples, was a small cubicle with a single entrance and grew into a larger chamber in time. The garbhagriha is made to house the main icon which is itself the focus of much ritual attention; (ii) the entrance to the temple which may be a portico or colonnaded hall that incorporates space for a large number of worshippers and is known as a mandapa; (iii) from the fifth century CE onwards, freestanding temples tend to have a mountain- like spire, which can take the shape of a curving shikhar in North India and a pyramidal tower, called a vimana, in South India; (iv) the vahan, i.e., the mount or vehicle of the temple’s main deity along with a standard pillar or dhvaj is placed axially before the sanctum. -

Glimpses of Indian Traditional Architecture

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 07 Issue: 05 | May 2020 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Glimpses of Indian Traditional Architecture Ar. Tania Bera Assistant Professor, Dept. of Architecture, G L Bajaj Group of Institutions, Mathura, U.P., India -------------------------------------------------------------------------***------------------------------------------------------------------------ Abstract- This paper narrates an essay on the major means it is a structure allocated for religious activities distinctive styles of traditional architecture of India from its such as prayer and sacrifice in front of deity. Here, some different regions which has acquired a lot of fame in the sort of offerings is made to the deity and other rituals are worldwide over decades. It’s a matter of pride to all the also performed [2]. A typical temple has a main building Indians for getting such an opportunity to experience and a larger precinct, sometimes containing many other varieties of traditional architecture spread throughout their buildings related with temple activity too. motherland as it has a huge asset of heritage and antiquity. A range of architectural varieties have developed in the 2.1. Temple Architecture: parts of the country due to its diversified socio-cultural, traditional and religious background as well as most The architecture of Hindu temples evolved since importantly climatic variations. Among all the aspects, the history with a great variety in it. Hindu temples are of different shapes and sizes— rectangular, octagonal and religious diversity has played a vital role in the development circular with different types of domes and gates. of distinctive architectural styles chronologically. It is the result of above-mentioned aspects which contributed towards the formation of a set of architectural assets within a single piece of land.