Research Packet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

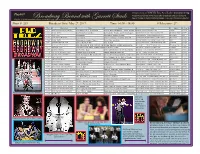

Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack

Originating on WMNR Fine Arts Radio [email protected] Playlist* Program is archived 24-48 hours after broadcast and can be heard Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack free of charge at Public Radio Exchange, > prx.org > Broadway Bound *Playlist is listed alphabetically by show (disc) title, not in order of play. Show #: 269 Broadcast Date: May 27, 2017 Time: 16:00 - 18:00 # Selections: 27 Time Writer(s) Title Artist Disc Label Year Position Comment File Number Intro Track Holiday Release Date Date Played Date Played Copy 3:24 Menken|Ashman|Rice|Beguelin Somebody's Got Your Back James Monroe Iglehart, Adam Jacobs & Aladdin Original Broadway Cast Disney 2014 Opened 3/20/2014 CDS Aladdin 15 2014 8/16/14 12/6/14 1/7/17 5/27/17 3:17 Irving Berlin Anything You Can Do Bernadette“friends” Peters and Tom Wopat Annie Get Your Gun - New Broadway Cast Broadway Angel 1999 3/4/1999 - 9/1/2001. 1045 perf. 2 Tony Awards: Best Revival. Best Actress, CDS Anni none 18 1999 6/7/08 5/27/17 Bernadette Peters. 3:30 Cole Porter Friendship Joel Grey, Sutton Foster Anything Goes - New Broadway Cast 2011 Ghostlight 2011 Opened 4/7/11 at the Stephen Sondheim Theater. THREE 2011 Tony Awards: Best Revival CDS Anything none 9 2011 12/10/113/31/12 5/27/17 of a Musical; Best Actress in a Musical: Sutton Foster; Best Choreography: Kathleen 2:50 John Kander/Fred Ebb Two Ladies Alan Cumming, Erin Hill & Michael Cabaret: The New Broadway Cast Recording RCA Victor 1998 3/19/1998 - 1/4/2004. -

Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street May 10 – June 7, 2020 Edu TABLE of CONTENTS

A NOISE WITHIN’S 2019-2020 REPERTORY THEATRE SEASON AUDIENCE GUIDE Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd The Demon Barber Of Fleet Street May 10 – June 7, 2020 Edu TABLE OF CONTENTS Character Map . 3 Synopsis . 4 About the Author: George Dibdin Pitt . 5 About the Adaptors: Christopher Bond, Hugh Wheeler, and Stephen Sondheim . 7 History of Sweeney Todd: A Timeline . 9 Change in the Air: The Transition from the Industrial Revolution to the Victorian Era . 10 Pretty Women: The Role of Women in 19th Century England . 11 The Great Divide: Social Inequality in Industrial and Victorian England . 14 Melodrama and Musicals . 15 The Evolution of the Sweeney Todd Story from Melodrama to Musical . 17 Themes . 18 Revenge . 18 Love and Desire . 18 Freedom and Captivity . 19 Madness . 19 Ken Booth Lighting Designer . 20 Additional Resources . 21 A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATION PROGRAMS MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY: Ann Peppers Foundation The Green Foundation Capital Group Companies Kenneth T . and Michael J . Connell Foundation Eileen L . Norris Foundation The Dick and Sally Roberts Ralph M . Parsons Foundation Coyote Foundation Steinmetz Foundation The Jewish Community Dwight Stuart Youth Fund Foundation 3 A NOISE WITHIN 2019/20 REPERTORY SEASON | Spring 2020 Study Guide Sweeney Todd CHARACTER MAP Mrs. Lovett The owner of a struggling meat pie shop . She knew Sweeney Todd before he was sent to Australia, and she helps him set up a barbershop when he returns to London . Sweeney Todd/Benjamin Barker An English barber formerly known Beggar Woman/Lucy Barker as Benjamin Barker . After spending A woman who has gone mad over 15 years wrongfully incarcerated in time . -

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV With onstage guests directors Brian Large and Jonathan Miller & former BBC Head of Music & Arts Humphrey Burton on Wednesday 30 April BFI Southbank’s annual Broadcasting the Arts strand will this year examine Opera on TV; featuring the talents of Maria Callas and Lesley Garrett, and titles such as Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) and The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), this season will show how television helped to democratise this art form, bringing Opera into homes across the UK and in the process increasing the public’s understanding and appreciation. In the past, television has covered opera in essentially four ways: the live and recorded outside broadcast of a pre-existing operatic production; the adaptation of well-known classical opera for remounting in the TV studio or on location; the very rare commission of operas specifically for television; and the immense contribution from a host of arts documentaries about the world of opera production and the operatic stars that are the motor of the industry. Examples of these different approaches which will be screened in the season range from the David Hockney-designed The Magic Flute (Southern TV/Glyndebourne, 1978) and Luchino Visconti’s stage direction of Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) to Peter Brook’s critically acclaimed filmed version of The Tragedy of Carmen (Alby Films/CH4, 1983), Jonathan Miller’s The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), starring Lesley Garret and Eric Idle, and ENO’s TV studio remounting of Handel’s Julius Caesar with Dame Janet Baker. Documentaries will round out the experience with a focus on the legendary Maria Callas, featuring rare archive material, and an episode of Monitor with John Schlesinger’s look at an Italian Opera Company (BBC, 1958). -

Spirit of Ame Rica Chee Rle a D E Rs

*schedule subject to change SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY MORNING MORNING MORNING MORNING MORNING MORNING MORNING Arrive at New York Hilton 7 am 8 am 6 am 8 am 5:30 am Shuttle Service Midtown for Event Check-in Coupon Breakfast Coupon Breakfast TODAY Show Coupon Breakfast Uniform Check Assemble/Depart Final Run Through Rhinelander 10 am–5 pm 8–11 am 9 am 8:30 am 9 am Grand Ballroom Gallery Luggage Drop-off Rehearsal Spectators and Performers Check out with Dress Rehearsal Rhinelander Gallery America’s Hall I Assemble/Check-out Spectator America’s Hall I 6 am America’s Hall I America’s Hall I Depart Hilton for Parade Event Check-in Spectators Return to hotel by 10:30 am America’s Hall I 8 am • Statue of Liberty Room Check. Move to Grand Ballroom 9 am–12 pm Assemble in • Harbor Cruise 92nd Macy’s Thanksgiving • Orientation Rhinelander Gallery for • 9/11 Memorial 9 am Spectators Day Parade!® • Packet Pick-up Big Apple Tour • One World Observatory Coupon Breakfast 10:30 am • Hotel Check-in Tour ends in Times Square View from 4th Floor Balcony 10 am–12 pm at 11 am 12:30 pm • Times Square Check out with • Central Park Spectator Return to hotel by Room Check. AFTERNOON AFTERNOON AFTERNOON AFTERNOON AFTERNOON AFTERNOON 10 am–5 pm 11:30 am Coupon Lunch 12 pm 1 pm 12 pm • If rooms are not available, Coupon Lunch Coupon Lunch Coupon Lunch Coupon Lunch Continue Activities Have a you may wait in safe America’s Hall II 1 pm 2 pm 2-6 pm TBD Aladdin journey Radio City Music Hall Macy’s / Empire State Building Check out with • Report to our New Amsterdam Theatre Christmas Spectacular Spectator home! Information Desk 214 W. -

AUGUSTANA COLLEGE THEATRE 2015-2016 Season Crime and Justice

AUGUSTANA COLLEGE THEATRE 2015-2016 Season Crime and Justice WVIK WVIKWVIK WVIis a proud WVIK partner in theWV Quad Cities’ WVIKarts and cultureWV WVIKcommunity WVIKWVIK WVIKWVIKWVIKwvik.org Augustana College Department of Theatre Arts, in conjunction with Opera@Augustana, proudly presents SWEENEY TODD The Demon Barber of Fleet Street A Musical Thriller Music and lyrics by Book by STEPHEN SONDHEIM HUGH WHEELER From an adaptation by CHRISTOPHER BOND Originally directed on Broadway by HAROLD PRINCE Orchestrations by JONATHAN TUNICK Originally produced on Broadway by RICHARD BARR, CHARLES WOODWARD, ROBERT FRYER, MARY LEA JOHNSON, MARTIN RICHARDS in association with DEAN and JUDY MANOS Directed by Music direction by JAY CRANFORD MICHELLE CROUCH SWEENEY TODD is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials also are supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR What a large undertaking in a short amount of time with Sondheim’s most difficult score! Kudos to the cast, crew, musical, technical and design team. Sondheim’s masterpiece about a wronged barber seeking revenge has long been a favorite of mine. Having seen the recent John Doyle Broadway revival on their final dress rehearsal, I caught Sondheim there looking perturbed. It had been deconstructed with the small cast playing their own instruments as they sang; clear storytelling had been lost. In our version, I wanted to focus completely on the relationships and reasons that drive Sweeney to action. A corrupt judge of powerful stature does the unimaginable, giving permission to a society in downward spiral to lose all sense of morality. -

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Broadway Green Alliance

Written and Edited by Michael Crow[ey BROADWAY green#alliance5 r tl a g w a v a r a © n € a rm ffi®img Wateries§ Water-Saving Technology Learn how theaters on Broadway and across the country are playing their part to conserve water. .i.. ``-I Theatre Manager Joseph Leads Way Find out how MTC is saving energy (and money) by using energy efficient HVAC and lighting technology. ffiGAm M©m©ify' B©aifdi Check Out Pies From Recent Events "wi;ife;#;7:nrtoe:d:ea;t%erre:=S£:[£°c::dw::he 44ot/c.. Cor4¢.72 B/ce! . a/ In The Heights See the back page of The Greer} Sheet for and Mj3redith Viein are joined by members photos of the BGA Times Square E-Waste of B;Wa!y Kids Care cnd Caap Broadray Event and BGA activities at Kids' Night. two recent winter events the BGA atKids'NightonBroatoay2olo. is continuing to educate and engage the Broadway community about reducing Beloev: Am E-:Waste Eueut cowection fiile, our industry's impact on the courtesy of evem s|]oin5orTmeRecycle! environment. ifefe trfuifegivefroe~" The BGA was on hand at Kids' Night on Broadway 2olo. Kids performing in Broadway shows and young patrons created "eco-art" displaying why they feel FOLLOW THE BGA ON: the BGA is so important. Similarly, the Broadway community braved the cold on Above: Dorothy Marring and George, December 16th to join us for our Times AND I faceb®ok^ I AkramfromL,VJest§ideStorysbaretbeir Square E-Waste Collection Event. sbowl eco-tips at the BGA E-Waste Eueut. -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No. -

329 Hill Street San Francisco CA 94114 O

Conservatory of Vocal Arts and Music Theater American Conservatory Theater San Francisco Conservatory of Music ! " # " $ % & ' " ( # ) * " Peter Maleitzke has recently completed a ten year residence at the American Conservatory Theater as Associate Artist and Music Director. This past year he continued on to Music Direct the first San Francisco performances of Adam Guettel's Myths and Hymns and as the Master Singing Teacher in the M.F.A. program. Recent projects: composing an original score for The Gamester, winning the Bay Area Theater Critics Circle Award for best Original Score, work-shopping Far From The Maddening Crowd, directing a cabaret production of Pippin, arranger and composer for The Three Sisters; musical direction for Carey Perloff's The Colossus of Rhodes; Brecht’s and Weill’s Happy End (featuring Betty Buckley); and the Gershwin's Of Thee I Sing (performed in three cities to sold out houses), world-premiere A.C.T. productions of The Difficulty of Crossing a Field ( Featuring Julia Migenes and Kronos) and Blitzstein's No for an Answer, A.C.T.'s The Threepenny Opera featuring Bebe Neuworth, Nancy Dusault, Lisa Vroman and Anika Noni Rose (Mr Maleitzke won the Bay Area Theatre Critics' Circle Award and BackStageWest Garland Award for this production). He was the conductor of the first national production of The Phantom of the Opera. His regional credits include Gypsy (Dean Goodman Award), A Little Night Music, Rags, and The Most Happy Fella and Closer Than Ever. Mr Maleitzke has worked extensively as a vocal coach, studio recording pianist and producer for most of the major networks and studios of Los Angeles, most notibly the series: Taken: Executive Producer: Steven Spielberg. -

JULIA CARTA Hair Stylist and Make-Up Artist

JULIA CARTA Hair Stylist and Make-Up Artist www.juliacarta.com PRESS JUNKETS/PUBLICITY EVENTS Matt Dillon - Grooming - WAYWARD PINES - London Press Junket Jeremy Priven - Grooming - BAFTA Awards - London Christian Bale - Grooming - AMERICAN HUSTLE - BAFTA Awards - London Naveen Andrews - Grooming - DIANA - London Press Junket Bruce Willis and Helen Mirren - Grooming - RED 2 - London Press Conference Ben Affleck - Grooming - ARGO - Sebastián Film Festival Press Junket Matthew Morrison - Grooming - WHAT TO EXPECT WHEN YOU’RE EXPECTING - London Press Junket Clark Gregg - Grooming - THE AVENGERS - London Press Junket Max Iron - Grooming - RED RIDING HOOD - London Press Junket and Premiere Mia Wasikowska - Hair - RESTLESS - Cannes Film Festival, Press Junket and Premiere Elle Fanning - Make-Up - SUPER 8 - London Press Junket Jamie Chung - Hair & Make-Up - SUCKERPUNCH - London Press Junket and Premiere Steve Carell - Grooming - DESPICABLE ME - London Press Junket and Premiere Mark Strong and Matthew Macfayden - Grooming - Cannes Film Festival, Press Junket and Premiere Michael C. Hall - Grooming - DEXTER - London Press Junket Jonah Hill - Grooming - GET HIM TO THE GREEK - London Press Junket and Premiere Laura Linney - Hair and Make-Up - THE BIG C - London Press Junket Ben Affleck - Grooming - THE TOWN - London and Dublin Press and Premiere Tour Andrew Lincoln - Grooming - THE WALKING DEAD - London Press Junket Rhys Ifans - Grooming - NANNY MCPHEE: THE BIG BANG (RETURNS) - London Press Junket and Premiere Bruce Willis - Grooming - RED - London