English.Pdf Purchasing Power Parity [PPP])—Much Lower Than 2 World Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Arab Emirates (Uae)

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: United Arab Emirates, July 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: UNITED ARAB EMIRATES (UAE) July 2007 COUNTRY اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴّﺔ اﻟﻤﺘّﺤﺪة (Formal Name: United Arab Emirates (Al Imarat al Arabiyah al Muttahidah Dubai , أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ (The seven emirates, in order of size, are: Abu Dhabi (Abu Zaby .اﻹﻣﺎرات Al ,ﻋﺠﻤﺎن Ajman , أ مّ اﻟﻘﻴﻮﻳﻦ Umm al Qaywayn , اﻟﺸﺎرﻗﺔ (Sharjah (Ash Shariqah ,دﺑﻲّ (Dubayy) .رأس اﻟﺨﻴﻤﺔ and Ras al Khaymah ,اﻟﻔﺠﻴﺮة Fajayrah Short Form: UAE. اﻣﺮاﺗﻰ .(Term for Citizen(s): Emirati(s أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ .Capital: Abu Dhabi City Major Cities: Al Ayn, capital of the Eastern Region, and Madinat Zayid, capital of the Western Region, are located in Abu Dhabi Emirate, the largest and most populous emirate. Dubai City is located in Dubai Emirate, the second largest emirate. Sharjah City and Khawr Fakkan are the major cities of the third largest emirate—Sharjah. Independence: The United Kingdom announced in 1968 and reaffirmed in 1971 that it would end its treaty relationships with the seven Trucial Coast states, which had been under British protection since 1892. Following the termination of all existing treaties with Britain, on December 2, 1971, six of the seven sheikhdoms formed the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The seventh sheikhdom, Ras al Khaymah, joined the UAE in 1972. Public holidays: Public holidays other than New Year’s Day and UAE National Day are dependent on the Islamic calendar and vary from year to year. For 2007, the holidays are: New Year’s Day (January 1); Muharram, Islamic New Year (January 20); Mouloud, Birth of Muhammad (March 31); Accession of the Ruler of Abu Dhabi—observed only in Abu Dhabi (August 6); Leilat al Meiraj, Ascension of Muhammad (August 10); first day of Ramadan (September 13); Eid al Fitr, end of Ramadan (October 13); UAE National Day (December 2); Eid al Adha, Feast of the Sacrifice (December 20); and Christmas Day (December 25). -

National Coordination Meeting

National Coordination Meeting Kyiv, 20 January 2021 Business of the Day 1. Q&A on Health Reform. Guest speakers: • Dr. Elina Dale, Adviser on Health Policy at WHO Ukraine • Anastasiya Brylova, Officer on Service Delivery, WHO Ukraine 2. Health Cluster Calendar 2021 3. Situation update: COVID-19 and ECA - WHO & partners 4. Update on Public Health Situation Analysis (PHSA) and ongoing assessments 5. Health Cluster M&E Framework 6. AOB • Update on Q4 2020 HRP and COVID-19 reporting • Update on COVID-19 Distribution Planning Tool (4W) • Health Cluster Assessment Database Health Cluster Meeting Q&A on Health Reform in Ukraine Dr. Elina Dale, Adviser on Health Policy Anastasiya Brylova , Officer on Service Delivery WHO Ukraine 2. HС Calendar Q1 & Q2 2021 # Month Date Q&A topics (TBC) 1 January 20 Health reform HeRAMS, Attacks on Health 2 February 3 Facilities 3 February 17 IPC & WASH 4 March 3 MHPSS 5 March 17 HIV/TB 6 April 14 Laboratories 7 April 28 Field focus: GCA & NGCA 8 May 12 Post COVID Rehab Human Rights/Protection and 9 May 26 Health 10 June 2 Epi and Surveillance 11 June 9 Behavioral Insights 12 June 16 Comms in Health 4. Public Health Situation Analysis (PHSA) • PHSA is part of the Public Health Information Services (PHIS) tools of the Global Health Cluster. • Provides all health sector partners with a common and comprehensive understanding of the public health situation in a crisis in order to inform evidence-based collective humanitarian health response planning. Focus of the assessment: Donetska & Luhanska Oblasts Eastern Ukraine -

Djibouti Health Expenditure Profile

Djibouti Health expenditure profile HEALTH SPENDING IN BRIEF WHO PAYS FOR HEALTH? 0.6% Health spending (% of GDP) 3.5 27.8% Health expenditure per capita (US$) 70 Public Out-of-pocket 45.8% Public spending on health per capita (US$) 32 Voluntary prepayment External Other GDP per capita (US$) 2,004 25.8% Life expectancy, both sexes (years) 62 RICHER COUNTRIES SPEND MORE ON HEALTH… …BUT NOT NECESSARILY AS A SHARE OF GDP 10,000 25 20 1,000 15 10 100 Health spending % of GDP 5 Health spending per capita (US$, log scale) 10 0 100 1,000 10,000 100,000 100 1,000 10,000 100,000 GDP per capita (US$, log scale) GDP per capita (US$, log scale) MORE GOVERNMENT SPENDING ON HEALTH IS ASSOCIATED WITH LOWER OUT-OF-POCKET SPENDING DOES GOVERNMENT SPEND ENOUGH ON HEALTH? 100 100 10 80 80 8 60 60 6 % US$ 40 40 4 20 20 2 Out-of-pocket spending % of health 0 0 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 Public spending on health % of GDP Health spending per capita (US$, bars) Government health spending % of total government spending (line) Djibouti PRIORITY OF HEALTH IN BUDGET ALLOCATION IS A POLITICAL CHOICE 25 20 15 10 5 Government health spending % of total government spending 0 India Egypt Kenya Congo Nigeria Angola Kiribati Ghana Bhutan SudanBoliviaJordan Tunisia Djibouti Vanuatu Armenia Ukraine Zambia Morocco Georgia Eswatini Lao PDRPakistan Myanmar TajikistanMongolia IndonesiaSri LankaViet Nam Honduras Cameroon MauritaniaMicronesia Cambodia Philippines Uzbekistan GuatemalaNicaraguaEl Salvador Timor-LesteBangladesh Côte d'Ivoire Cabo Verde Solomon -

Trends Gross and Net Spending Non-Cash Benefits

8. PUBLIC EXPENDITURE ON PENSIONS Key Results Public spending on cash old-age pensions and survivors’ benefits in the OECD increased from an average of 6.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) to 8.0% between 2000 and 2015. Public pensions are often the largest single item of social expenditure, accounting for 18.4% of total government spending on average in 2015. Greece spent the largest proportion of national income Trends on public pensions among OECD countries in 2015: 16.9% of Public pension spending was fairly stable as a GDP. Other countries with high gross public pension proportion of GDP over the period 1990-2015 in spending are in continental Europe, with Italy at 16.2% and ten countries: Australia, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Lithuania, Austria, France and Portugal at between 13% and 14% of New Zealand, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden and Switzerland. GDP. Public pensions generally account for between one- fourth and one-third of total public expenditure in these Public pension expenditure increased by more than 4 countries. points of GDP between 2000 and 2015 in Finland, Greece, Portugal and Turkey, and between 2 and 3 percentage points Iceland and Mexico spent 2.1% and 2.2% of GDP on in France, Italy, Japan and Spain. public pensions, respectively. Korea is also a low spender at 2.9% of GDP. Mexico has a relative young population, which Gross and net spending is also the case but to a lesser extent in Iceland, where much of retirement income is provided by compulsory The penultimate column of the table shows public occupational schemes (see the next indicator of “Pension- spending in net terms: after taxes and contributions paid on benefit expenditures: Public and private”), leaving a lesser benefits. -

Mauritius Budget Highlights 2020-2021

Mauritius Budget Highlights 2020/21 June 4, 2020 KPMG.com/mu Contents 03 KPMG View 08 Budget Financials 10 Economic Outlook Global Business & 14 Regulatory 19 Corporate Tax 23 Personal Tax 26 Indirect Taxes 31 Tax Administration 34 Appendices © 2020 KPMG,KPMG Taxa Mauritian Services partnership Ltd, a Mauritian and a limited member liability firm of company the KPMG and network a member of independent firm of the KPMG member network firms ofaffiliated independent with KPMG memb Inteer firmsrnational affiliated Cooperative, with KPMG a Swiss International entity. All Cooperative, rights reserved.. a Swiss 2 entity. All rights reserved.. Document Classification: KPMG Confidential FOREWORD KPMG View An array of social measures for economic revival The Minister of Finance, Economic Planning and economy, building of a pharmaceutical industry and Development, presented on 4 June 2020 the 2020- promotion of regional partnerships. 2021 budget speech entitled “Our new normal: the The tourism industry received a number of incentives economy of life”. such as the possibility to convert hotels into service The Government has embarked into the post COVID- apartments which can be sold individually, a two year 19 era with measures presented under a “Plan de no-licence fee period for Tourism and Beach Authority Relance de L’Investissement et de L’Economie”, operators, a waiver of rental of State land for one year, “Major Structural Reforms” and “Securing and the increase in the rebate scheme for renovation Sustainable and Inclusive Development”. and restructuring to 100% until 2022. As the country navigates its way out of the COVID-19 Reducing concentration and promoting local pandemic with a projected contraction of 11% this manufacturing year, we also face an ageing population and a high Local manufacturers will benefit with supermarkets gross public sector debt ratio of 83.4% (net 72.7%). -

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): Analysis of Economic Studies

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): Analysis of Economic Studies James K. Jackson Specialist in International Trade and Finance June 30, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44551 The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): Analysis of Economic Studies Summary Congress plays a major role in formulating and implementing U.S. trade policy through its legislative and oversight responsibilities. Under the U.S. Constitution, Congress has the authority to regulate foreign commerce, while the President has the authority to conduct foreign relations. In 2015, Congress reauthorized Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) that( 1) sets trade policy objectives for the President to negotiate in trade agreements; (2) requires the President to engage with and keep Congress informed of negotiations; and (3) provides for Congressional consideration of legislation to implement trade agreements on an expedited basis, based on certain criteria. The United States is considering the recently-concluded Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) among the United States and 11 other countries. The 12 TPP countries signed the agreement in February 2016, but the agreement must be ratified by each country before it can enter into force. In the United States this requires implementing legislation by Congress. The agreement is viewed by the participants as a “comprehensive and high standard” mega- regional free trade agreement that may hold the promise of greater economic opportunities and closer economic and strategic ties among the negotiating parties. For Members of Congress and others, international trade and trade agreements may offer the prospect of improved national economic welfare. Such agreements, however, have mixed effects on U.S. domestic and foreign interests, both economic and political. -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Budget Analysis for Investments in Children in Saint Lucia

Budget Analysis for Investments in Children in Saint Lucia BUDGET ANALYSIS FOR INVESTMENTS IN CHILDREN IN SAINT LUCIA Published by UNICEF Office for the Eastern Caribbean Area First Floor, UN House Marine Gardens, Hastings Christ Church Barbados Tel: (246) 467 6000 Fax: (246) 426 3812 Email: [email protected] Website: www.unicef.org/easterncaribbean This Study was commissioned by the UNICEF Office for the Eastern Caribbean Area and UN Women Multi-Country Office - Caribbean The contents do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of the organizations. Authors: Zina Nimeh, Arthur Van de Meerendonk, Franziska Gassmann, Jouke Wortelboer, Eli Stoykova and Daphne Francoise Nimeh, Z., Van de Meerendonk, A., Gassmann, F., Wortelboer, J. and Stoykova, E., Francoise, D. (2015). Budget Analysis for Investments in Children in Saint Lucia, UNICEF Office for the Eastern Caribbean Area. All rights reserved. 2015 Budget Analysis for Investments in Children in Saint Lucia CONTENTS Acknowledgments x Executive summary 2 1 Introduction 12 1.1 Structure of the report 13 1.2 Government actors 13 1.3 Data and methodology 13 1.4 Limitations 14 1.5 Process 14 2 Economic and Social Context 16 2.1 Economic and fiscal environment 16 2.2 Fiscal operations and management and the social budget 19 2.3 Demographic trends 21 2.4 Labour market 23 2.5 Poverty and child well-being 25 2.6 Conclusion 30 3 Education 32 3.1 Short overview of the education system in Saint. Lucia 32 3.2 Policies and planning 33 3.2.1 Laws and other basic regulations concerning education -

Fiscal and Structural Reforms in Saint Lucia: Towards a Comprehensive

FISCAL AND STRUCTURAL REFORMS IN SAINT LUCIA: TOWARDS A COMPREHENSIVE AGENDA NOVEMBER 2016 FISCAL AND STRUCTURAL REFORMS IN SAINT LUCIA: TOWARDS A MORE COMPREHENSIVE AGENDA vi Disclaimer Copyright © Caribbean Development Bank (CDB). The opinions, findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the staff of CDB and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of CDB, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent. This work may be reproduced, with attribution to CDB, for any non-commercial purpose. The use of CDB's name for any purpose other than for attribution, and the use of CDB's logo shall be subject to a separate written licence agreement between CDB and the user and is not authorized as part of this licence. No derivative work is allowed. CDB does not necessarily own each component of the content contained within this document and therefore does not warrant that the use of any third-party owned individual component or part contained in this work will not infringe on the rights of those third parties. Any risks of claims resulting from such infringement rest solely with the user. CDB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. Any dispute related to the use of the works of CDB that cannot be settled amicably shall be submitted to arbitration pursuant to the UNCITRAL rules. Nothing herein shall constitute or be deemed to constitute a waiver of the privileges and immunities of CDB, all of which are specifically reserved. FISCAL AND STRUCTURAL REFORMS IN SAINT LUCIA: TOWARDS A MORE COMPREHENSIVE AGENDA ii Acknowledgements The Caribbean Development Bank expresses appreciation to the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank for its contribution to the Report, as well as to the Staff of the Ministry of Finance, especially the Research and Policy Unit, who provided invaluable assistance on this project. -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

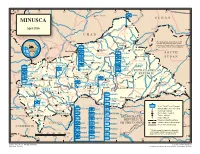

MINUSCA T a Ou M L B U a a O L H R a R S H Birao E a L April 2016 R B Al Fifi 'A 10 H R 10 ° a a ° B B C H a VAKAGA R I CHAD

14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° ZAMBIA Am Timan é Aoukal SUDAN MINUSCA t a ou m l B u a a O l h a r r S h Birao e a l April 2016 r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh Garba The boundaries and names shown ouk ahr A Ouanda and the designations used on this B Djallé map do not imply official endorsement Doba HQ Sector Center or acceptance by the United Nations. CENTRAL AFRICAN Sam Ouandja Ndélé K REPUBLIC Maïkouma PAKISTAN o t t SOUTH BAMINGUI HQ Sector East o BANGORAN 8 BANGLADESH Kaouadja 8° ° SUDAN Goré i MOROCCO u a g n i n i Kabo n BANGLADESH i V i u HAUTE-KOTTO b b g BENIN i Markounda i Bamingui n r r i Sector G Batangafo G PAKISTAN m Paoua a CAMBODIA HQ Sector West B EAST CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro Yangalia RWANDA CENTRAL AFRICAN BANGLADESH m a NANA Mbrès h OUAKA REPUBLIC OUHAM u GRÉBIZI HAUT- O ka Bria Yalinga Bossangoa o NIGER -PENDÉ a k MBOMOU Bouca u n Dékoa MAURITANIA i O h Bozoum C FPU CAMEROON 1 OUHAM Ippy i 6 BURUNDI Sector r Djéma 6 ° a ° Bambari b ra Bouar CENTER M Ouar Baoro Sector Sibut Baboua Grimari Bakouma NANA-MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO- BASSE MBOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KOTTO m Bossembélé GRIBINGUI M b angúi bo er ub FPU BURUNDI 1 mo e OMBELLA-MPOKOYaloke Zémio u O Rafaï Boali Kouango Carnot L Bangassou o FPU BURUNDI 2 MAMBÉRÉ b a y -KADEI CONGO e Bangui Boda FPU CAMEROON 2 Berberati Ouango JTB Joint Task Force Bangui LOBAYE i Gamboula FORCE HQ FPU CONGO Miltary Observer Position 4 Kade HQ EGYPT 4° ° Mbaïki Uele National Capital SANGHA Bondo Mongoumba JTB INDONESIA FPU MAURITANIA Préfecture Capital Yokadouma Tomori Nola Town, Village DEMOCRATICDEMOCRATIC Major Airport MBAÉRÉ UNPOL PAKISTAN PSU RWANDA REPUBLICREPUBLIC International Boundary Salo i Titule g Undetermined Boundary* CONGO n EGYPT PERU OFOF THE THE CONGO CONGO a FPU RWANDA 1 a Préfecture Boundary h b g CAMEROON U Buta n GABON SENEGAL a gala FPU RWANDA 2 S n o M * Final boundary between the Republic RWANDA SERBIA Bumba of the Sudan and the Republic of South 0 50 100 150 200 250 km FPU SENEGAL Sudan has not yet been determined. -

Security Sector Reform in the Central African Republic

Security Sector Reform in the Central African Republic: Challenges and Priorities High-level dialogue on building support for key SSR priorities in the Central African Republic, 21-22 June 2016 Cover Photo: High-level dialogue on SSR in the CAR at the United Nations headquarters on 21 June 2016. Panellists in the center of the photograph from left to right: Adedeji Ebo, Chief, SSRU/OROLSI/DPKO; Jean Willybiro-Sako, Special Minister-Counsellor to the President of the Central African Republic for DDR/SSR and National Reconciliation; Miroslav Lajčák, Minister of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic; Joseph Yakété, Minister of Defence of Central African Republic; Mr. Parfait Onanga-Anyanga, Special Representative of the Secretary-General for the Central African Republic and Head of MINUSCA. Photo: Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic The report was produced by the Security Sector Reform Unit, Office of Rule of Law and Security Institutions, Department of Peacekeeping Operations, United Nations. © United Nations Security Sector Reform Unit, 2016 Map of the Central African Republic 14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° AmAm Timan Timan The boundaries and names shown and the designations é oukal used on this map do not implay official endorsement or CENTRAL AFRICAN A acceptance by the United Nations. t a SUDAN lou REPUBLIC m u B a a l O h a r r S h Birao e a l r B Al Fifi 'A 10 10 h r ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh k Garba Sarh Bahr Aou CENTRAL Ouanda AFRICAN Djallé REPUBLIC Doba BAMINGUI-BANGORAN Sam