Generation Iron: “No, You Couldn't Do What I Do”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SLS 21RS-918 ORIGINAL 2021 Regular Session SENATE

SLS 21RS-918 ORIGINAL 2021 Regular Session SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 63 BY SENATOR BERNARD COMMENDATIONS. Commends Ronnie Coleman on being inducted into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame. 1 A RESOLUTION 2 To commend Ronnie Coleman on being inducted into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame. 3 WHEREAS, Ronnie Dean Coleman was born in Monroe, Louisiana, on May 13, 4 1964, and was a native of Bastrop, Louisiana; and 5 WHEREAS, he reached a high-level playing football during high school which 6 motivated him to lift weights and set out on his fitness journey; and 7 WHEREAS, Ronnie's performance as a football player led to a scholarship offer to 8 Grambling State University to study accounting and play football; and 9 WHEREAS, he played football as a middle linebacker with the GSU Tigers under 10 coach Eddie Robinson; and 11 WHEREAS, Ronnie Coleman graduated cum laude from Grambling State University 12 in 1984 with a bachelor's degree in accounting; and 13 WHEREAS, upon graduation he moved to Texas in search of work and eventually 14 became a police officer in Arlington, Texas, where he was an officer from 1989 to 2000 and 15 a reserve officer until 2003; and 16 WHEREAS, Ronnie joined the world famous Metroflex Gym, where he quickly 17 developed a bond with the owner, Brian Dobson; and 18 WHEREAS, Mr. Dobson ultimately gave Ronnie a lifetime free membership if he Page 1 of 3 SLS 21RS-918 ORIGINAL SR NO. 63 1 allowed Mr. Dobson to train him for competition; and 2 WHEREAS, Ronnie's hard work and determination lead to him winning the 1990 Mr. -

'Freaky:' an Exploration of the Development of Dominant

From ‘Classical’ To ‘Freaky:’ an Exploration of the Development of Dominant, Organised, Male Bodybuilding Culture Dimitrios Liokaftos Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London Submitted for the Degree of PhD in Sociology February 2012 1 Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Dimitrios Liokaftos Signed, 2 Abstract Through a combination of historical and empirical research, the present thesis explores the development of dominant, organized bodybuilding culture across three periods: early (1880s-1930s), middle (1940s-1970s), and late (1980s-present). This periodization reflects the different paradigms in bodybuilding that the research identifies and examines at the level of body aesthetic, model of embodied practice, aesthetic of representation, formal spectacle, and prevalent meanings regarding the 'nature' of bodybuilding. Employing organized bodybuilding displays as the axis for the discussion, the project traces the gradual shift from an early bodybuilding model, represented in the ideal of the 'classical,' 'perfect' body, to a late-modern model celebrating the 'freaky,' 'monstrous' body. This development is shown to have entailed changes in notions of the 'good' body, moving from a 'restorative' model of 'all-around' development, health, and moderation whose horizon was a return to an unsurpassable standard of 'normality,' to a technologically-enhanced, performance- driven one where 'perfection' assumes the form of an open-ended project towards the 'impossible.' Central in this process is a shift in male identities, as the appearance of the body turns not only into a legitimate priority for bodybuilding practitioners but also into an instance of sport performance in bodybuilding competition. Equally central, and related to the above, is a shift from a model of amateur competition and non-instrumental practice to one of professional competition and extreme measures in search of the winning edge. -

Download High-Intensity Training the Mike Mentzer Way, Mike

High-Intensity Training the Mike Mentzer Way, Mike Mentzer, John R. Little, McGraw-Hill, 2002, 0071383301, 9780071383301, 288 pages. A PAPERBACK ORIGINALHigh-intensity bodybuilding advice from the first man to win a perfect score in the Mr. Universe competitionThis one-of-a-kind book profiles the high-intensity training (HIT) techniques pioneered by the late Mike Mentzer, the legendary bodybuilder, leading trainer, and renowned bodybuilding consultant. His highly effective, proven approach enables bodybuilders to get results--and win competitions--by doing shorter, less frequent workouts each week. Extremely time-efficient, HIT sessions require roughly 40 minutes per week of training--as compared with the lengthy workout sessions many bodybuilders would expect to put in daily.In addition to sharing Mentzer's workout and training techniques, featured here is fascinating biographical information and striking photos of the world-class bodybuilder--taken by noted professional bodybuilding photographers--that will inspire and instruct serious bodybuilders and weight lifters everywhere.. DOWNLOAD HERE http://bit.ly/1f8Qgh8 The World Gym Musclebuilding System , Joe Gold, Robert Kennedy, 1987, Health & Fitness, 179 pages. Briefly describes the background of World's Gym, tells how to get started in bodybuilding, and discusses diet, workout routines, and competitions. The Gold's Gym Training Encyclopedia , Peter Grymkowski, Edward Connors, Tim Kimber, Bill Reynolds, Sep 1, 1984, Health & Fitness, 272 pages. Demonstrates exercises and weight training routines for developing one's biceps, chest, shoulders, back, thighs, hips, triceps, abdomen, and forearms. Solid gold training the Gold's Gym way, Bill Reynolds, 1985, Health & Fitness, 216 pages. Discusses the basics of bodybuilding and provides guidance on the use of free weights and exercise equipment to develop the body. -

Lou Ferrigno

Lou Ferrigno 1951-Present Early Life and His Athletic Success ● Born in Brooklyn, NY in 1951, Lou contracted an ear infection as a child that resulted in 80% hearing loss. ● Lou entered the bodybuilding scene by taking first place as Eastern Teenage Mr. America in 1971, and then went on to win over a dozen competition awards over 20 years from 1971-1994. ● During his role The Hulk on The Incredible Hulk, Ferrigno played professional football in Canada. Television and Movie Roles ● Ferrigno starred as The Hulk on The Incredible Hulk, which he had to beat out Arnold Schwarzenegger to get. ○ Lou’s success on television as The Hulk began in the late 1970s, which is still his lingering claim to fame. ● Lou has also participated in dozens of movies and television projects almost every year since, his most recent being John Bradley in a film entitled Instant Death. More Than a Movie Star ● Lou is currently putting in time as a peace officer with the San Luis Obispo County sheriff’s office. ○ Starting in 2012, Ferrigno has dedicated about 20 hours a month as a volunteer reserve. ○ Lou attended the police academy to properly prepare, stating, “People assume it’s just an honorary thing… I’m very happy to be a real-life hero, protecting life and property.” ● Ferrigno is also the inspiration and co-founder of Ferrigno Fit, “A lifestyle brand that celebrates positive, healthy living… to build personalized transformation programs aimed at helping individuals achieve their fitness goals.” ○ This venture is an understandable outcropping of his life experience as a professional bodybuilder, fitness trainer, and consultant. -

Aobs Newsletter

AOBS NEWSLETTER The Association of Oldetime Barbell & Strongmen An International Iron Game Organization – Organized in 1982 (Vic Boff – Founder and President 1917-2002) P.O Box 680, Whitestone, NY 11357 (718) 661-3195 E-mail: [email protected] Web-Site: www.aobs.cc AUGUST 2009 and excellence. I thank them all very deeply for Our Historic 26th Annual Reunion - A Great agreeing to grace us with their presence. Beginning To the “Second” 25 Years! Then there was the veritable “Who’s Who” that came Quite honestly, after the record-breaking attendance and from everywhere to honor these great champions and to cavalcade of stars at our 25th reunion last year, we were join in a celebration of our values. Dr. Ken Rosa will worried about being able to have an appropriately have more to say about this in his report on our event, strong follow-up in our 26th year, for three reasons. but suffice it to say that without the support of the First, so many people made a special effort to attend in famous and lesser known achievers in attendance, the 2008, there was a concern that we might see a big drop event wouldn’t have been what it was. off in 2009. Second, there was the economy, undoubtedly the worst in decades, surely the worst since Then there was the staff of, and accommodations our organization began. Third, there were concern about offered by, the Newark Airport Marriott Hotel. We had the “swine flu” that was disproportionately impacting a very positive experience with this fine facility last the NY Metropolitan area. -

Cultural Arts Among Deaf People Robert Panara

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Articles 1983 Cultural arts among deaf people Robert Panara Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/article Recommended Citation Panara, R. (1983). Cultual arts among deaf people. Gallaudet Today, 13(3), 12-16. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -- --- cultural Arts Among Deaf people by Robert F. Panara he publicationof that remarkable novel, Roots, by TAlex Haley,and its .dramatizationon nationaltelevision has probably created more awareness of "the Black . experience" in America than any other single work since 1852,when Harriet Beecher Stowe published Unde Tom~ Cabin. It is also important to note that Roots, unlike Unde Tom~ Cabin, was the work of a Blackauthor an~ that Black . persons played the leading roles on Tv. This "cultural breakthrough" has great significance when we consider the state of the cultural arts among deaf people. To begin with, there is.the outstanding achievement of the National Theatre of the Deaf which has helped awaken the public to "Deaf Awareness." Since its establishment in 1967, NTDhas influenced millions of hearing people, in the theatre and on TV.. In their han~s, the sign language of the so-called "deaf and dumb~' has '- "The Camel Driver" is a dry-point etching by Cadwallader Washbum. Mr. Washbum, who graduated from Gallaudet In 1890, was not only an artist of International note, but also a journalist, oologlst, entomologist, world traveler, and explorer. -

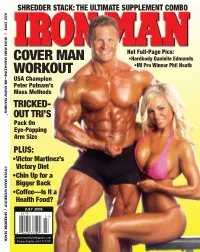

COVER MAN WORKOUT / SHREDDER STACK CC1 PP-JULY2008 F.Indd 1

SHREDDER STACK: THE ULTIMATE SUPPLEMENT COMBO JULY 2008 / IRON MAN MAGAZINE— JULY ™ Hot Full-Page Pics: COVER MAN •Hardbody Danielle Edmonds WORKOUT •IM Pro Winner Phil Heath WE KNOW TRAINING USA Champion Peter Putnam’s Mass Methods TRICKED- ™ OUT TRI’S Pack On Eye-Popping Arm Size PLUS: COVER MAN WORKOUT / SHREDDER STACK •Victor Martinez’s Victory Diet •Chin Up for a Bigger Back •Coffee—Is It a Health Food? JULY 2008 $5.99 www.IronManMagazine.com Please display until 7/1/08 CC1_PP-JULY2008_F.indd1_PP-JULY2008_F.indd 1 55/2/08/2/08 77:21:30:21:30 PMPM IM2902_A 8/1/05 11:43 AM Page 1 Hardcore internet company SDI-LABS offers mail order distribution to the public I Lift, Therefore ™ FREE LEGAL STEROIDS.com The Magazine with every purchase! ® 1 Bottle - $79.95 D-BOL 4 Bottles - $239.85 Save $79.95! *Since its introduction just over 18 months ago, D-BOL is fast becoming the most OH popular oral pro-anabolic available. D-BOL has a special formulation containing OH methadrostenol™ that may exert a pronounced ergogenic action in the body after oral HO H administration similar to those experienced by users of methandrostenolone. Methandrostenolone is the most popular oral anabolic steroid currently used today. OH D-BOL, however, lacks the c17 alpha alkylated configuration, which may HO comparatively lower the risks of certain associated side effects. Several users of D- H O BOL are reporting of extremely dramatic muscle size and strength gains. Empirical data suggests myocytic anabolism (muscle growth) relative to methandrostenolone **METHADROSTENOL™ tablets with notably less water retention. -

DVD Profiler

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure Animation Family Comedy2003 74 minG Coll.# 1 C Barry Bostwick, Jason Alexander, The endearing tale of Disney's animated classic '101 Dalmatians' continues in the delightful, all-new movie, '101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London A Martin Short, Bobby Lockwood, Adventure'. It's a fun-filled adventure fresh with irresistible original music and loveable new characters, voiced by Jason Alexander, Martin Short and S Susan Blakeslee, Samuel West, Barry Bostwick. Maurice LaMarche, Jeff Bennett, T D.Jim Kammerud P. Carolyn Bates C. W. Garrett K. SchiffM. Geoff Foster 102 Dalmatians Family 2000 100 min G Coll.# 2 C Eric Idle, Glenn Close, Gerard Get ready for outrageous fun in Disney's '102 Dalmatians'. It's a brand-new, hilarious adventure, starring the audacious Oddball, the spotless A Depardieu, Ioan Gruffudd, Alice Dalmatian puppy on a search for her rightful spots, and Waddlesworth, the wisecracking, delusional macaw who thinks he's a Rottweiler. Barking S Evans, Tim McInnerny, Ben mad, this unlikely duo leads a posse of puppies on a mission to outfox the wildly wicked, ever-scheming Cruella De Vil. Filled with chases, close Crompton, Carol MacReady, Ian calls, hilarious antics and thrilling escapes all the way from London through the streets of Paris - and a Parisian bakery - this adventure-packed tale T D.Kevin Lima P. Edward S. Feldman C. Adrian BiddleW. Dodie SmithM. David Newman 16 Blocks: Widescreen Edition Action Suspense/Thriller Drama 2005 102 min PG-13 Coll.# 390 C Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David From 'Lethal Weapon' director Richard Donner comes "a hard-to-beat thriller" (Gene Shalit, 'Today'/NBC-TV). -

The History of Bodybuilding: International and Hungarian Aspects

Művelődés-, Tudomány- és Orvostörténeti Folyóirat 2020. Vol. 10. No. 21. Journal of History of Culture, Science and Medicine e-ISSN: 2062-2597 DOI: 10.17107/KH.2020.21.165-178 The History of Bodybuilding: International and Hungarian Aspects A testépítés története: nemzetközi és magyar vonatkozások Petra Németh doctoral student dr. Andrea Gál docent Doctoral School of Sport Sciences, University of Physical Education [email protected], [email protected] Initially submitted Sept 2, 2020; accepted for publication Oct..20, 2020 Abstract Bodybuilding is a scarcely investigated cultural phenomenon in social sciences, and, in particular, historiography despite the fact that its popularity both in its competitive and leisure form has been on the rise, especially since the 1950s. Development periods of this sport are mainly identified with those iconic competitors, who were the most dominant in the given era, and held the ‘Mr. Olympia’ title as the best bodybuilders. Nevertheless, sources reflecting on the evolution of organizational background and the system of competitions are more difficult to identify. It is similarly challenging to investigate the history of female bodybuilding, which started in the 19th century, but its real beginning dates back to the 1970s. For analysing the history of international bodybuilding, mainly American sources can be relied on, but investigating the Hungarian aspects is hindered by the lack of background materials. Based on the available sources, the objective of this study is to discover the development -

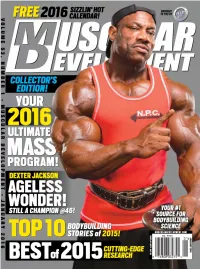

Muscular Development Is Your Number-One Source for Building Muscle, and for the Latest Research and Best Science to Enable You to Train Smart and Effectively

BONUS SIZE BONUS SIZE %MORE % MORE 20 FREE! 25 FREE! MUSCLETECH.COM MuscleTech® is America’s #1 Selling Bodybuilding Supplement Brand based on cumulative wholesale dollar sales 2001 to present. Facebook logo is owned by Facebook Inc. Read the entire label and follow directions. © 2015 NEW! PRO SERIES The latest innovation in superior performance from This complete, powerful performance line features the MuscleTech® is now available exclusively at Walmart! same clinically dosed key ingredients and premium The all-new Pro Series is a complete line of advanced quality you’ve come to trust from MuscleTech® over supplements to help you maximize your athletic the last 20 years. So you have the confi dence that potential with best-in-class products for every need: you’re getting the best research-based supplements NeuroCore®, an explosive, fast-acting pre-workout; possible – now at your neighborhood Superstore! CreaCore®, a clinically dosed creatine amplifier; MyoBuild®4X, a powerful amino BCAA recovery formula; AlphaTest®, a Clinically dosed, lab-tested key ingredients max-strength testosterone booster; and Muscle Builder, Formulated and developed based on the extremely powerful, clinically dosed musclebuilder. multiple university studies Plus, take advantage of the exclusive Bonus Size of Fully-disclosed formulas – no hidden blends our top-selling sustained-release protein – PHASE8TM. Instant mixing and amazing taste ERICA M ’S A # SELLING B Gŭŭ S OD IN UP YBUILD ND PLEMENT BRA BONUS SIZE MORE 33%FREE! EDITOR’s LETTER BY STEVE BLECHMAN, Publisher and Editor-in-Chief DEXTER JACKSON IS ‘THE BLADE’ BODYBUILDING’S NEXT GIFT? eing the number-one bodybuilder in the world is an achievement that commands respect from fans and fellow competitors alike. -

Attaining Olympus: a Critical Analysis of Performance-Enhancing Drug Law and Policy for the 21St Century

Franco Book Proof (Do Not Delete) 4/16/19 11:35 PM ATTAINING OLYMPUS: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF PERFORMANCE-ENHANCING DRUG LAW AND POLICY FOR THE 21ST CENTURY ALEXANDRA M. FRANCO1 ABSTRACT While high-profile doping scandals in sports always garner attention, the public discussion about the use of performance-enhancing substances ignores the growing social movement towards enhancement outside of sports. This Article discusses the flaws in the ethical origins and justifications for modern anti-doping law and policy. It analyzes the issues in the current regulatory scheme through its application to different sports, such as cycling and bodybuilding. The Article then juxtaposes those issues to general anti-drug law applicable to non-athletes seeking enhancement, such as students and professionals. The Article posits that the current regulatory scheme is harmful not only to athletes but also to people in general—specifically to their psychological well-being—because it derives from a double social morality that simultaneously shuns and encourages the use of performance-enhancing drugs. I. INTRODUCTION “Everybody is going to do what they do.” — Phil Heath, Mr. Olympia champion.2 The relationship between performance-enhancing drugs and American society has been problematic for the past several decades. High- profile doping scandals regularly garner media attention—for example, 1. © Alexandra M. Franco, J.D. The Author is an Affiliated Scholar at the Institute for Science, Law and Technology at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. She previously worked as a Judicial Law Clerk for the Honorable Franklin U. Valderrama in the Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois (the views expressed in this Article are solely those of the Author, and do not represent those of Equal Justice Works or Cook County). -

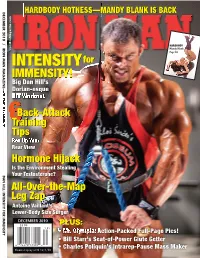

Intensityfor

DECEMBER 2010 / IRON MAN MAGAZINE— DECEMBER 2010 / IRON MAN MAGAZINE— HARDBODY HOTNESS—MANDY BLANK IS BACK TERRY, ™ Vertical Web ad- dress is obscured by logo. HARDBODY Mandy Blank IronManMagazine.com Page 182 INTENSITY for IMMENSITY! Big Dan Hill’s WE KNOW TRAINING Dorian-esque HIT Workout Back-Attack ™ 6Training DAN HILL: INTENSITY FOR IMMENSITY Tips Rev Up Your Rear View Hormone Hijack Is the Environment Stealing Your Testosterone? All-Over-the-Map Leg Zap Antoine Vaillant’s Lower-Body Size Surger DECEMBER 2010 $5.99 PLUS: • Mr. Olympia: Action-Packed Full-Page Pics! • Bill Starr’s Seat-of-Power Glute Getter • Charles Poliquin’s Intrarep-Pause Mass Maker Please display until 12/1/10 FC_DEC_2010_F.indd 1 10/5/10 12:14:35 PM CONTEWE KNOW TRAINING™ NTS DECEMBER 2010 80 FEATURES DAN HILL 56 TRAIN, EAT, GROW 134 Hit the growth threshold with 4X training, and you’ll build new mass—guaranteed. 80 INTENSITY FOR IMMENSITY New pro Dan Hill, 24, works at getting huge—in and out of the gym. 98 HORMONE HIJACK Is the environment stealing your muscle gains? It’s very possible, and Jerry Brainum has some solutions. 116 A BODYBUILDER IS BORN: GENERATIONS Ron Harris hammers home some old-school iron wisdom: Treat all your children the same. 120 CANADIAN WHEELS Cory Crow gets the lowdown on Antoine Vaillant’s all-over-the-map leg zap. 120 CANADIAN WHEELS Contents_F.indd 18 10/4/10 5:49:56 PM DECEMBER 2010 / IRON MAN MAGAZINE— HARDBODY HOTNESS—MANDY BLANK IS BACK Dan Hill appears ™ Vertical Web ad- on this month’sdress is obscured HARDBODY Mandy Blank IronManMagazine.com cover.