BLACK LIVES MATTER and BLACK POWER By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art in America the EPIC BANAL

Art in America THE EPIC BANAL BY: Amy Sherald, Tyler Mitchell May 7, 2021 10:08am Tyler Mitchell: Untitled (Blue Laundry Line), 2019. Amy Sherald (https://www.artnews.com/t/amy-sherald/): A Midsummer Afternoon Dream, 2020, oil on canvas, 106 by 101 inches. Tyler Mitchell and Amy Sherald—two Atlanta-born, New York–based artists—both capture everyday joy in their images of Black Americans. Recurring motifs in Mitchell’s photographs, installations, and videos include outdoor space and fashionable friends. Sherald, a painter, shares similar motifs: her colorful paintings with pastel palettes show Black people enjoying American moments, their skin painted in grayscale, the backgrounds and outfits flat. Both are best known for high-profile portrait commissions: in 2018 Mitchell became the first Black photographer to have a work grace the cover of Vogue. That shot of Beyoncé was followed, more recently, by a portrait of Kamala Harris for the same publication. Michelle Obama commissioned Amy Sherald to paint her portrait, and last year Vanity Fair asked Sherald to paint Breonna Taylor for a cover too. Below, the artists discuss the influence of the South on their work, and how they navigate art versus commercial projects. —Eds. Amy Sherald: Precious jewels by the sea, 2019, oil on canvas, 120 by 108 inches. TYLER MITCHELL: Amy, we spoke before about finding freedom and making your own moments of joy. I think of Precious jewels by the sea [2019]—your painting of two couples at the beach, showing the men standing with the women on their shoulders—as a moment that you constructed. -

Amanda Gorman

1. Click printer icon (top right or center bottom). 2. Change "destination"/printer to "Save as PDF." English Self-Directed Learning Activities 3. Click "Save." Language Learning Center 77-1005, Passport Rewards SL53. Interesting People – Amanda Gorman SL 53. Interesting People – Amanda Gorman Student Name: _________________________________ Student ID Number: ________________________ Instructor: _____________________________________ Level: ___________Date: ___________________ For media links in this activity, visit the LLC ESL Tutoring website for Upper Level SDLAs. Find your SDLA number to see all the resources to finish your SDLA. Section 1: What is Interesting? Mark everything in the list below that you find interesting. Definition of Interesting from Longman’s Dictionary of Contemporary English: “if something is interesting, you give it your attention because it seems unusual or exciting or provides information that you did not know about.” Key vocabulary words are given in the next section. Having a twin sister. Writing poetry. Writing poetry and performing it for Michelle Obama, Nike ads, and the Super Bowl, to name a few. Being raised by a single mother in Los Angeles (L.A.) who is a middle school teacher in Watts. Being Black. Being a Black activist. Overcoming a speech impediment. Winning the first ever offered US National Youth Poet Laureate at 19-years-old. Winning the first ever offered L.A. Youth Poet Laureate at 16. Starting a nonprofit organization that encourages youth leadership and poetry workshops. Starting a nonprofit organization when 16 years old. Attending Harvard and graduating with a GPA over 3.5 (cum laude). Speaking at the US Presidential Inauguration. Being the youngest poet to ever present at a Presidential Inauguration. -

Standing Confident and Assured, She Took the Podium to Recite Her Poetry

Standing confident and assured, she took the podium to recite her poetry. Amanda Gorman, first national youth poet laureate of the United States, raised by a single mother, Harvard graduate, stood at the microphone safely distant and unmasked so that those listening could hear her powerful words delivered with passion. In her poem “The Hill We Climb” Gorman spoke into the time and circumstances of her life as young African-American woman with her words of honesty and hope. As she was in the process of writing that poem for President Joe Biden’s inauguration, a violent mob, stoked to anger by the damaging words of a man holding on to his power, stormed the Capitol in Washington, DC. Though the context of her poem was a moment of political transition in another country, Gorman’s words reached out across borders. She said that in writing her poem, her intent was speak healing into division. Not shying away from her country’s racist and colonial history, its struggles, and also its dreams, her words ultimately landed on hope for all people: Scripture tells us to envision that everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree and no one shall make them afraid. 1 Mark’s gospel this morning tells us of Jesus’ message and the call of those first disciples. But the story begins with words which hang ominously in the air: “Now after John was arrested.” Right at the beginning of Mark’s account there arises that very brief mention of John the Baptist’s arrest. Mark doesn’t explain the arrest until we get to chapter six of his gospel account. -

Kamala Harris and Amanda Gorman

MARCH 2021 WOMEN OF INFLUENCE: Kamala Harris and Amanda Gorman TABLE OF CONTENTS Video Summary & Related Content 3 Video Review 4 Before Viewing 5 Talk Prompts 6 Digging Deeper 8 Activity: Poetry Analysis 13 Sources 14 News in Review is produced by Visit www.curio.ca/newsinreview for an CBC NEWS and Curio.ca archive of all previous News In Review seasons. As a companion resource, go to GUIDE www.cbc.ca/news for additional articles. Writer: Jennifer Watt Editor: Sean Dolan CBC authorizes reproduction of material VIDEO contained in this guide for educational Host: Michael Serapio purposes. Please identify source. Senior Producer: Jordanna Lake News In Review is distributed by: Supervising Manager: Laraine Bone Curio.ca | CBC Media Solutions © 2021 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation WOMEN OF INFLUENCE: Kamala Harris and Amanda Gorman Video duration – 14:55 In January 2021, Kamala Harris became the highest-ranking woman in U.S. history when she was sworn in as the first female vice-president — and the first Black woman and person of South Asian descent to hold the position. Born in California, Harris has ties to Canada having attended high school in Montreal. Another exciting voice heard at the U.S. presidential inauguration was a young woman who may well be changing the world with her powerful words. Amanda Gorman, 23, is an American poet and activist. In 2017, she became the first person in the U.S. to be named National Youth Poet Laureate. This is a look at these two Women of Influence for 2021. Related Content on Curio.ca • News in Review, December 2020 – U.S. -

2015 Year in Review

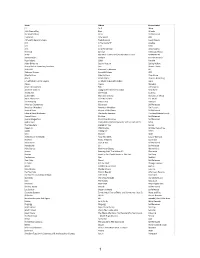

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday ESOL Choice

ESOL Choice Board for Grades 6-8: Week of February 8th Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Take a look at some excerpts from When writing, we place quotation Take a look at some excerpts Mari Copeny, also known Sometimes a writer does an article about Amanda Gorman, marks around the exact words that a from an article about Ian Brock, as “Little Miss Flint,” wrote not state everything the first National Youth Poet person says. These words are called the 15 year old founder of a letter to (then) President plainly. When you figure Laureate: a direct quotation. Most of the time, Chicago’s Dream Hustle Code Barack Obama in 2014 out details based on what you use a comma to separate the program: asking for help with the you know and what you “This afternoon, with her reading conversation words from the direct dirty, polluted drinking are reading, you are of an original composition titled quotation. Place a question mark or “Brock turned his anger over water in her hometown of making inferences. When The Hill We Climb, she did just an exclamation point, when used, experiences like these into Flint, Michigan. Mari’s you put together pieces that- and, in doing so, became the inside the quotation marks. action. At the age of eight, he recognition of a problem in of information in a text, youngest inaugural poet in United worked with his parents to her community and the you are drawing States history.” Click here to play Punctuation start the nonprofit Dream letter she wrote inspired conclusions. -

RIGHTS CLAIMS THROUGH MUSIC a Study on Collective Identity and Social Movements

RIGHTS CLAIMS THROUGH MUSIC A study on collective identity and social movements Dzeneta Sadikovic Department of Global and Political Studies Human Rights III (MR106S) Bachelor thesis, 15hp 15 ETC, Fall/2019 Supervisor: Dimosthenis Chatzoglakis Abstract This study is an analysis of musical lyrics which express oppression and discrimination of the African American community and encourage potential action for individuals to make a claim on their rights. This analysis will be done methodologically as a content analysis. Song texts are examined in the context of oppression and discrimination and how they relate to social movements. This study will examine different social movements occurring during a timeline stretching from the era of slavery to present day, and how music gives frame to collective identities as well as potential action. The material consisting of song lyrics will be theoretically approached from different sociological and musicological perspectives. This study aims to examine what interpretative frame for social change is offered by music. Conclusively, this study will show that music functions as an informative tool which can spread awareness and encourage people to pressure authorities and make a claim on their Human Rights. Keywords: music, politics, human rights, freedom of speech, oppression, discrimination, racism, culture, protest, social movements, sociology, musicology, slavery, civil rights, African Americans, collective identity List of Contents 1. Introduction p.2 1.1 Topic p.2 1.2 Aim & Purpose p.2 1.3 Human Rights & Music p.3 1.4 Research Question(s) p.3 1.5 Research Area & Delimitations p.3 1.6 Chapter Outline p.5 2. Theory & Previous Research p.6 2.1 Music As A Tool p.6 2.2 Social Movements & Collective Behavior p.8 2.2.1 Civil Rights Movement p.10 3. -

Milwaukee Holiday Lights Festival

MILWAUKEE HOLIDAY LIGHTS FESTIVAL — 20 SEASONS OF LIGHTS & SIGHTS — NOVEMBER 15, 2018 - JANUARY 1, 2019 DOWNTOWN MILWAUKEE • milwaukeeholidaylights.com IT’S THE MOST WONDERFUL TIME OF THE Y’EAR! MILWAUKEE HOLIDAY LIGHTS FESTIVAL – MILWAUKEE HOLIDAY LIGHTS FESTIVAL 20 SEASONS OF LIGHTS & SIGHTS KICK-OFF EXTRAVAGANZA November 15, 2018 – January 1, 2019 Thu, November 15 | 6:30pm Nobody does the holidays quite like Milwaukee! In celebration of our 20th Pre-show entertainment beginning at 5:30pm season, we’re charging up the town to light millions of faces. From all-day Pere Marquette Park adventures to evening escapes, guests of all ages will delight in our merry In celebration of 20 seasons, we’re delivering measures. So hop to something extraordinary! a magical lineup full of holiday cheer. Catch performances by Platinum, Prismatic Flame, #MKEholidaylights Milwaukee Youth Symphony Orchestra, Jenny Thiel, Young Dance Academy, and cast members from Milwaukee Repertory Theater’s “A Christmas Carol” and Black Arts MKE’s “Black Nativity” presented by Bronzeville Arts Ensemble. Fireworks and a visit from Santa will top off the night. Plus, after the show, take in downtown’s newly lit scenes with free Jingle Bus rides presented by Meijer and powered by Coach USA. If you can’t make the party, tune into WISN 12 for a live broadcast from 6:30pm to 7pm. “WISN 12 Live: Holiday Lights Kick-Off” will be co-hosted by Adrienne Pedersen and Sheldon Dutes. 3RD 2ND SCHLITZ PARK TAKE IN THE SIGHTS ABOARD THE JINGLE BUS CHERRY presented by meijer LYON Thu – Sun, November 15 – December 30 | 6pm to 8:20pm VLIET WATER OGDEN PROSPECT AVENUE FRANKLIN Plankinton Clover Apartments – 161 W. -

Blacklivesmatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2021 #BlackLivesMatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change Jamillah Bowman Williams Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Naomi Mezey Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Lisa O. Singh Georgetown University, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2387 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3860435 California Law Review Online, Vol. 12, Reckoning and Reformation symposium. This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law and Society Commons #BlackLivesMatter— Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change Jamillah Bowman Williams*, Naomi Mezey**, and Lisa Singh*** Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 I. Methodology ............................................................................................ 5 II. BLM: From Contemporary Social Movement to Structural Change ..... 6 A. Black Lives Matter as a Social Media Powerhouse ................. 6 B. Tweets and Streets: The Dynamic Relationship between Online and Offline Activism ................................................. 12 C. A Theory of How to Move from Social Media -

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020 1 7 Anti-Racist Books Recommended by Educators and Activists from the New York Magazine https://nymag.com/strategist/article/anti-racist-reading- list.html?utm_source=insta&utm_medium=s1&utm_campaign=strategist By The Editors of NY Magazine With protests across the country calling for systemic change and justice for the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, many people are asking themselves what they can do to help. Joining protests and making donations to organizations like Know Your Rights Camp, the ACLU, or the National Bail Fund Network are good steps, but many anti-racist educators and activists say that to truly be anti-racist, we have to commit ourselves to the ongoing fight against racism — in the world and in us. To help you get started, we’ve compiled the following list of books suggested by anti-racist organizations, educators, and black- owned bookstores (which we recommend visiting online to purchase these books). They cover the history of racism in America, identifying white privilege, and looking at the intersection of racism and misogyny. We’ve also collected a list of recommended books to help parents raise anti-racist children here. Hard Conversations: Intro to Racism - Patti Digh's Strong Offer This is a month-long online seminar program hosted by authors, speakers, and social justice activists Patti Digh and Victor Lee Lewis, who was featured in the documentary film, The Color of Fear, with help from a community of people who want and are willing to help us understand the reality of racism by telling their stories and sharing their resources. -

23 Black Leaders Who Are Shaping History Today

23 Black Leaders Who Are Shaping History Today Published Mon, Feb 1 20219:45 AM EST Updated Wed, Feb 10 20211:08 PM EST Courtney Connley@CLASSICALYCOURT Vice President Kamala Harris, poet Amanda Gorman, Sen. Raphael Warnock, nurse Sandra Lindsay and NASA astronaut Victor Glover. Photo credit: Getty; Photo Illustration: Gene Kim for CNBC Make It Black Americans have played a crucial role in helping to advance America’s business, political and cultural landscape into what it is today. And since 1976, every U.S. president has designated the month of February as Black History Month to honor the achievements and the resilience of the Black community. While CNBC Make It recognizes that Black history is worth being celebrated year-round, we are using this February to shine a special spotlight on 23 Black leaders whose recent accomplishments and impact will inspire many generations to come. These leaders, who have made history in their respective fields, stand on the shoulders of pioneers who came before them, including Shirley Chisholm, John Lewis, Maya Angelou and Mary Ellen Pleasant. 6:57 How 7 Black leaders are shaping history today Following the lead of trailblazers throughout American history, today’s Black history-makers are shaping not only today but tomorrow. From helping to develop a Covid-19 vaccine, to breaking barriers in the White House and in the C-suite, below are 23 Black leaders who are shattering glass ceilings in their wide-ranging roles. Kamala Harris, 56, first Black, first South Asian American and first woman Vice President Vice President Kamala Harris. -

The Apology | the B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero Scene & Heard

November-December 2017 VOL. 32 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES N O . 6 IN THIS ISSUE One Week and a Day | Poverty, Inc. | The Apology | The B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero scene & heard BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Learn more about Baker & Taylor’s Scene & Heard team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications Experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Baker & Taylor is the Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, most experienced in the backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging business; selling A/V expertise products to libraries since 1986. 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review One Week and a Day and target houses that are likely to be empty while mourners are out. Eyal also goes to the HHH1/2 hospice where Ronnie died (and retrieves his Oscilloscope, 98 min., in Hebrew w/English son’s medical marijuana, prompting a later subtitles, not rated, DVD: scene in which he struggles to roll a joint for Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.99, Blu-ray: $39.99 the first time in his life), gets into a conflict Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood Wr i t e r- d i r e c t o r with a taxi driver, and tries (unsuccessfully) to hide in the bushes when his neighbors show Editorial Assistant: Christopher Pitman Asaph Polonsky’s One Week and a Day is a up with a salad.