Art in America the EPIC BANAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design by the Yard; Textile Printing from 800 to 1956

INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI_NVINOSHilWS S3 I a Vy a n_LI BRAR I ES SMITHS0N1AN_INSTITIJ S3iyvMan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi nvinoshiiws S3iyv S3iyvaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiJ-SNi nvinoshiiws saiav l"'lNSTITUTION^NOIinillSNl"'NVINOSHiIWS S3 I MVy 8 ll'^LI B RAR I ES SMITHSONIAN INSTITI r- Z r- > Z r- z J_ ^__ "LIBRARIES Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi nvinoshiiws S3IMV rs3 1 yvy an '5/ o ^INSTITUTION N0IiniliSNI_NVIN0SHilWS"S3 I H VM 8 IT^^LI B RAR I ES SMITHSONIANJNSTITl rS3iyvyan"LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN^INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHIIWS S3iav ^"institution NOIiniliSNI NviNOSHiiws S3iyvaan libraries Smithsonian instit 9'^S3iyvaan^LIBRARIEs'^SMITHS0NlAN INSTITUTION NOIifliliSNI NVINOSHilWs'^Sa ia\i IVA5>!> W MITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS S3ldVyan LI B R AR I ES SMITHSONI; Z > </> Z M Z ••, ^ ^ IVINOSHilWs'^S3iaVaan2LIBRARIES"'SMITHSONlAN2lNSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI_NVINOSHill JMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS S3IMVHan LIBRARIES SMITHSONI jviNOSHiiws S3iavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiifiiiiSNi nvinoshii I ES SMITHSONI MITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIifliliSNI NVIN0SHilWS"'S3 I ava a n~LI B RAR < |pc 351 r; iJt ^11 < V JVIN0SHilWS^S3iavaan~'LIBRARIES^SMITHS0NIAN"'lNSTITUTI0N NOIiniliSNI^NVINOSHil — w ^ M := "' JMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS S3iavaan LI B RAR I ES SMITHSONI ^^ Q X ' "^ — -«^ <n - ^ tn Z CO wiNOSHiiws S3iavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi_NviNOSHii _l Z _l 2 -• ^ SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS SSiavaail LIBRARIES SMITHSON NVINOSHilWS S3iavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiisNi nvinoshi t'' 2 .... W 2 v^- Z <^^^x E . ^ ^-^ /Si«w*t DESIGN BY THE YARD TEXTILE PRINTING FROM 800 TO 1956 THE COOPER UNION MUSEUM FOR THE ARTS OF DECORATION NEW YORK ACKNOWLEDGMENT In assembling material for the exhibition, the Museum has received most helpful suggestions and information from the following, to whom are given most grateful thanks: Norman Berkowitz John A. -

The Diaries of Mariam Davis Sidebottom Houchens

THE DIARIES OF MARIAM DAVIS SIDEBOTTOM HOUCHENS VOLUME 7 MAY 15, 1948-JUNE 9, 1957 Copyright 2015 © David P. Houchens TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 7 Page Preface i Table of Contents ii Book 69- Saturday, May 15, 1948-Wednesday, July 7, 1948 1 Book 70- Thursday, July 8, 1948-Wednesday, September 8, 1948 25 Book 71- Thursday, September 9, 1948-Saturday, December 11, 1948 29 Book72- Sunday, December 12, 1948-Wednesday, January 26, 1949 32 Book 73- Thursday, January 27, 1949-Wednesday, February 23, 1949 46 Book 74- Thursday, February 24, 1949-Saturday, March 26, 1949 51 Book 75- Sunday, March 27, 1949-Saturday, April 23, 1949 55 Book 76- Sunday, April 24, 1949-Thursday, Friday July 1, 1949 61 Book 77- Saturday, July 2, 1949-Tuesday, August 30, 1949 68 Book 78- Wednesday, August 31, 1949-Tuesday, November 22, 1949 78 Book79- Wednesday, November 23, 1949-Sunday, February 12, 1950 85 Book 80- Monday, February 13, 1950-Saturday, April 22, 1950 92 Book 81- Sunday, April 23, 1950-Friday, June 30, 1950 97 Book 82- Saturday, July 1, 1950-Friday, September 29, 1950 104 Book 83- Saturday, September 30, 1950-Monday, January 8, 1951 113 Book 84- Tuesday, January 9, 1951-Sunday, February 18, 1951 117 Book 85- Sunday, February 18, 1951-Monday, May 7, 1951 125 Book 86- Monday, May 7, 1951-Saturday, June 16, 1951 132 Book 87- Sunday, June 17, 1951-Saturday 11, 1951 144 Book 88- Sunday, November 11, 1951-Saturday, March 22, 1952 150 Book 89- Saturday, March 22, 1952-Wednesday, July 9, 1952 155 ii Book 90- Thursday, July 10, 1952-Sunday, September 7, 1952 164 -

Along the Pacific

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 All Along the Pacific Corina Brittleston Calsing University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Calsing, Corina Brittleston, "All Along the Pacific" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 928. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/928 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. All Along the Pacific A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Film, Theatre and Communication Arts By Corina Bittleston Calsing BA, English, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo May 2009 Copyright 2009, Corina Calsing ii Dedication This work is dedicated to all men in my family who are members of E Clampus Vitus. They instilled in me a love for the historical, the hysterical, and the bizarre. -

The Obama Portraits, in Art History and Beyond Richard J

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. contents Foreword Kim Sajet vi Unveiling the Unconventional: Kehinde Wiley’s Portrait of Barack Obama Taína Caragol 1 “Radical Empathy”: Amy Sherald’s Portrait of Michelle Obama Dorothy Moss 25 The Obama Portraits, in Art History and Beyond Richard J. Powell 51 The Obama Portraits and the National Portrait Gallery as a Site of Secular Pilgrimage Kim Sajet 83 The Presentation of the Obama Portraits: A Transcript of the Unveiling Ceremony 98 Notes 129 Selected Bibliography 137 Credits 139 For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Taína Caragol Unveiling the Unconventional Kehinde Wiley’s Portrait of Barack Obama On February 12, 2018, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery unveiled the portraits of President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama. The White House and the museum had worked together to commission the paintings, and, in many ways, the lead- up to the ceremony had followed tradition. But this time something was different. The atmosphere was infused with the coolness of the there- present Obamas, and the event, which was made memorable with speeches from the sitters, the artists, and Smithsonian officials, erupted with applause at the first glimpse of these two highly unconventional portraits. Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of the president portrays a man of extraordinary presence, sitting on an ornate chair in the midst of a lush botanical setting (p. -

Valeska Soares B

National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels As of 8/11/2020 1 Table of Contents Instructions…………………………………………………..3 Rotunda……………………………………………………….4 Long Gallery………………………………………………….5 Great Hall………………….……………………………..….18 Mezzanine and Kasser Board Room…………………...21 Third Floor…………………………………………………..38 2 National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels The large-print guide is ordered presuming you enter the third floor from the passenger elevators and move clockwise around each gallery, unless otherwise noted. 3 Rotunda Loryn Brazier b. 1941 Portrait of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, 2006 Oil on canvas Gift of the artist 4 Long Gallery Return to Nature Judith Vejvoda b. 1952, Boston; d. 2015, Dixon, New Mexico Garnish Island, Ireland, 2000 Toned silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Susan Fisher Sterling Top: Ruth Bernhard b. 1905, Berlin; d. 2006, San Francisco Apple Tree, 1973 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Sharon Keim) 5 Bottom: Ruth Orkin b. 1921, Boston; d. 1985, New York City Untitled, ca. 1950 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Joel Meyerowitz Mwangi Hutter Ingrid Mwangi, b. 1975, Nairobi; Robert Hutter, b. 1964, Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany For the Last Tree, 2012 Chromogenic print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Tony Podesta Collection Ecological concerns are a frequent theme in the work of artist duo Mwangi Hutter. Having merged names to identify as a single artist, the duo often explores unification 6 of contrasts in their work. -

Annual Report 2018-2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 1 2 CONTENTS A Letter from Our Executive Director 4 A Letter from the Chair of the Board 5 Our Namesakes 6 Celebrating Our History: 50 Years of LGBTQ Health 8 Timeline 12 Reflections on our History 14-17 Our Patients 18 A Year in Photos 22 Our Staff 24 Callen-Lorde Brooklyn 26 Board of Directors 28 Senior Leadership 29 Howard J. Brown Society 30 Our Supporters 32 ABOUT US Callen-Lorde is the global leader in LGBTQ healthcare. Since the days of Stonewall, we have been transforming lives in LGBTQ communities through excellent comprehensive care, provided free of judgment and regardless of ability to pay. In addition, we are continuously pioneering research, advocacy and education to drive positive change around the world, because we believe healthcare is a human right. 3 A LETTER FROM OUR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, Supporters, and Community Members, Fifty years ago, Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson were among the first brick throwers in the Stonewall Rebellions, igniting the fire that began – slowly – to change LGBTQ lives. That same year, the beginnings of Callen- Lorde started when two physicians opened the St. Mark’s Health Clinic to provide free healthcare services to the ‘hippies, freaks, and queers’ in the East Village. Today, that little clinic is Callen-Lorde Community Health Center - a network of health centers soon to be in three boroughs of New York City and improving LGBTQ health worldwide. What has not changed in 50 years is our commitment to serving people regardless of ability to pay, our passion for health equity and justice for our diverse LGBTQ communities and people living with HIV, and our belief that access to healthcare is a human right and not a privilege. -

The Apology | the B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero Scene & Heard

November-December 2017 VOL. 32 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES N O . 6 IN THIS ISSUE One Week and a Day | Poverty, Inc. | The Apology | The B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero scene & heard BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Learn more about Baker & Taylor’s Scene & Heard team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications Experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Baker & Taylor is the Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, most experienced in the backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging business; selling A/V expertise products to libraries since 1986. 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review One Week and a Day and target houses that are likely to be empty while mourners are out. Eyal also goes to the HHH1/2 hospice where Ronnie died (and retrieves his Oscilloscope, 98 min., in Hebrew w/English son’s medical marijuana, prompting a later subtitles, not rated, DVD: scene in which he struggles to roll a joint for Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.99, Blu-ray: $39.99 the first time in his life), gets into a conflict Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood Wr i t e r- d i r e c t o r with a taxi driver, and tries (unsuccessfully) to hide in the bushes when his neighbors show Editorial Assistant: Christopher Pitman Asaph Polonsky’s One Week and a Day is a up with a salad. -

The 2020 TJFP Team

On the Precipice of Trans Justice Funding Project 2020 Annual Report Contents 2 Acknowledgements 4 Terminology 5 Letter from the Executive Director 11 Our Grantmaking Year in Review 20 Grantees by Region and Issue Areas 22 The 2020 TJFP Team 27 Creating a Vision for Funding Trans Justice 29 Welcoming Growth 34 Funding Criteria 35 Some of the Things We Think About When We Make Grants 37 From Grantee to Fellow to Facilitator 40 Reflections From the Table 43 Our Funding Model as a Non-Charitable Trust 45 Map of 2020 Grantees 49 Our 2020 Grantees 71 Donor Reflections 72 Thank You to Our Donors! This report and more resources are available at transjusticefundingproject.org. Acknowledgements We recognize that none of this would have been possible without the support of generous individuals and fierce communities from across the nation. Thank you to everyone who submitted an application, selected grantees, volunteered, spoke on behalf of the project, shared your wisdom and feedback with us, asked how you could help, made a donation, and cheered us on. Most of all, we thank you for trusting and supporting trans leadership. A special shoutout to our TJFP team, our Community Grantmaking Fellows and facilitators; Karen Pittelman; Nico Amador; Cristina Herrera; Zakia Mckensey; V Varun Chaudhry; Stephen Switzer at Rye Financials; Raquel Willis; Team Dresh, Jasper Lotti; butch.queen; Shakina; Nat Stratton-Clarke and the staff at Cafe Flora; Rebecca Fox; Alex Lee of the Grantmakers United for Trans Communities program at Funders for LGBT Issues; Kris -

Annual Report 2019 - 2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 - 2020 1 2 ABOUT US Callen-Lorde is the global leader in LGBTQ healthcare. Since the days of Stonewall, we have been transforming lives in LGBTQ communities through excellent comprehensive care, provided free of judgment and regardless of ability to pay. In addition, we are continuously pioneering research, advocacy and education to drive positive change around the world, because we believe healthcare is a human right. CONTENTS History and Namesakes . 4 A Letter from our Executive Director Wendy Stark . 6 A Letter from our Board Chair Lanita Ward-Jones ������������������������������������������������������������ 7 COVID-19 Impact . 8 Callen-Lorde Brooklyn ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������10 Advocacy & Policy ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������10 The Keith Haring Nurse Practitioner Postgraduate Fellowship in LGBTQ+ Health ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 12 Callen-Lorde by the Numbers . 14 Senior Staff and Board of Directors ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 16 Howard J. Brown Society . .17 John B. Montana Society �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������17 -

Bed and Bath Essentials

BED AND BATH ESSENTIALS Pillows, Sheets, Blankets, Towels and Other Textile Basics for Healthcare 1 MEDLINE Superior Quality and Value Enhancing Patient Satisfaction Medline Bed and Bath Essentials Where Innovation Never Sleeps. As one of the leading providers of textile products and solutions to the healthcare market, Medline never stops innovating. For more than 100 years, we’ve continually introduced cutting edge fabrics, products and services to help make you more efficient, cost effective, patient-centered and environmentally friendly. » INNOVATIONS THAT ADVANCE CARE: In this catalog, you will find the healthcare industry’s finest and broadest collection of quality pillows, blankets, sheets, towels and other textile necessities, including our latest innovations that focus on skin health, patient comfort and durability. Look for products with the lightbulb symbol to indicate our newest advancements. Innovation » OUR EXCLUSIVE FEELS LIKE HOME® COLLECTION: Indicated with the Feels Like Home® icon, these elegant sheets, ultra-soft blankets and plush towels are designed to pamper patients while enhancing the perception of your facility. Look for our newest item—the lightweight, two-tone spread blanket (page 27) that keeps patients warm without weighing them down. Feels Like Home® » PERFORMAX™ SUSTAINABLE TEXTILES: Engineered with advanced 100% polyester fabric, our new PerforMAX textiles are designed to look better and perform longer, even after repeated washings. PerforMAX products also have the greensmart logo to signify they have undergone a rigorous review for sustainability throughout the entire greensmart™ product lifecycle. Look for new PerforMAX products, including the LT Silvertouch underpad (page 34), Envelope Contour Sheets (page 22) and Spectrum Spread Blankets (page 28). -

Amy Sherald-Inspired Portraits

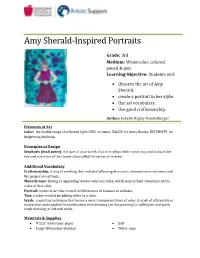

Amy Sherald-Inspired Portraits Grade: 3rd Medium: Watercolor, colored pencil & pen Learning Objective: Students will: • Observe the art of Amy Sherald. • create a portrait in her style. • Use art vocabulary. • Use good craftsmanship. Author: Juliette Ripley-Dunkelberger Elements of Art Color: the visible range of reflected light. HUE: its name; VALUE: its tints/shades; INTENSITY: its brightness/dullness. Principles of Design Emphasis (focal point): the part of an artwork that is emphasized in some way and attracts the eye and attention of the viewer; also called the center of interest. Additional Vocabulary Craftsmanship: A way of working that includes following directions, demonstrates neatness and the proper use of tools. Monochrome: having or appearing to have only one color, which may include variations on the value of that color. Portrait: works of art that record the likenesses of humans or animals. Tint: a value created by adding white to a color Wash: a painting technique that leaves a semi-transparent layer of color. A wash of diluted ink or watercolor paint applied in combination with drawing (on dry painting) is called pen and wash, wash drawing, or ink and wash. Materials & Supplies • 9”x12” watercolor paper • Salt • Large Watercolor brushes • Water cups • Cardstock – print body worksheet • Erasers • Pencils • Body templates • Drawing pens • Masking tape • 3 Skin color sets of colored pencils • Colored pencils • Pattern sheet • Paper towels • Ruler Context (History and/or Artists) Amy Sherald, (American b. Columbus, GA 1973) received degrees in painting from 2 different colleges. She was an International Artist-in-Residence in Panama. Sherald was the first woman to win the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition grand prize. -

Amy Sherald the Great American Fact

Press Release Amy Sherald The Great American Fact 20 March – 6 June 2021 Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles South Gallery Los Angeles… On 20 March, Amy Sherald, one of America’s defining contemporary portraitists, will unveil new paintings in her first West Coast solo exhibition. On view at Hauser & Wirth’s Downtown Arts District complex in Los Angeles, ‘The Great American Fact’ presents five works produced in 2020 that extend the artist’s technical innovations and distinctive visual language. Sherald is acclaimed for paintings of Black Americans at leisure that achieve the authority of landmarks in the grand tradition of social portraiture – a tradition that for too long excluded the Black men, women, and families whose lives have been inextricable from the narrative of the American experience. Subverting the genre of portraiture and challenging accepted notions of American identity, Sherald attempts to restore a broader, fuller picture of humanity. She positions her subjects as ‘symbolic tools that shift perceptions of who we are as Americans, while transforming the walls of museum galleries and the canon of art history – American art history, to be more specific.’ Sherald routinely draws upon literary references in her exhibition and the titles for her paintings. With ‘The Great American Fact’ she is referencing the 1892 book by educator Anna Julia Cooper, who wrote that Black people are ‘‘the great American fact’; the one objective reality on which scholars sharpened their wits, and at which orators and statesmen fired their eloquence.’ Sherald here employs Cooper’s statement as a framework for considering ‘public Blackness’ – the way Black American identity is shaped in the public realm.