Red Feather Journal, Volume 9, Issue 1, Spring 2018 a Touch of Color

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

TV Shows with Animals Instructions

TV Shows with Animals Instructions ● There will be trivia about different tv shows with animal as its main character from the 1950’s and 60’s ● After you guess the TV show you can go to the answer slide where there will be the answer along with a link to the TV show ● There will also be discussion questions for each show Trivia ● A show about a smart and fearless collie who performs a series of heroic tasks for her human owners and friends ● For the first several years of the series, she lived on family farms, before moving on to work with forest rangers in the wilderness and ultimately settling in at Holden ranch, a ranch for troubled children ● Can you guess the TV show? Answer ● Lassie ● Link to show: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BV1 Nyf_u1AA Discussion Questions ● Did you ever watch Lassie? ● Did you like it? ● Who did you watch it with? Trivia ● An American black bear befriends a family in the Everglades ● It is about their adventures in the Florida Everglades ● Can you guess the TV show? Answer ● Gentle Ben ● Link to show: https://www.youtube.com/w atch?v=zHt6tkUEhCI Discussion Questions ● Did you ever watch Gentle Ben? ● Did you like it? ● Who did you watch it with? Trivia ● This show is about a New York lawyer Oliver Wendell Douglas who longs for a simpler way of life, so he buys a farm, sight unseen, and moves there to live off the land, with his wife, Lisa ● The show highlights the collision of small-town life and Lisa's sophisticated ways ; she insists on wearing full-length gowns and ostentatious jewelry, even on the farm -

Production Information

Production Information Ladies’ man David teaches his dating tricks to his lonely, widowed grandfather Joe, while using those same tricks to meet Julie, the woman of his dreams. But as David's foolproof techniques prove to be anything but, the same techniques quickly transform Grandpa Joe into the Don Juan of the retirement community. But soon it's up to Grandpa Joe to teach David that the best way to win the game of love is not to play games at all. Story Films presents “Play The Game,” starring Paul Campbell, Andy Griffith, Doris Roberts, Marla Sokoloff and Liz Sheridan. The film is produced, written and directed by Marc Fienberg, and also features Clint Howard, Geoffrey Owens and Juliette Jeffers. The creative team includes Director of Photography Gavin Kelly, Production Designer Chris Anthony Miller, and Editor Kimberley Generous White. Jennifer Schaefer is the film’s Co-Producer, and the Music Supervisor is Robin Urdang. This film has been rated PG-13 for sexual content and language. The Story Twenty-eight year-old David (Paul Campbell) is an expert at using his psychological skills to manipulate customers in his job as a luxury car salesman – and manipulate women in his life as a ladies' man. He’s perfected his surefire steps, which include setting up elaborate “chance” encounters with women, never letting them discover that they're actually being pursued – only to be discarded. When David's lonely, widowed grandpa, Joe (Andy Griffith), asks for David's help in re- entering the dating world to find a companion, David agrees to teach him all his secret tricks. -

159 Minutes Directed & Produced by Robert Altman Written by Joan

APRIL 17, 2007 (XIV:13) (1975) 159 minutes Directed & produced by Robert Altman Written by Joan Tewkesbury Original music by Arlene Barnett, Jonnie Barnett, Karen Black, Ronee Blakley, Gary Busey, Keith Carradine, Juan Grizzle, Allan F.Nicholls, Dave Peel, Joe Raposo Cinematography by Paul Lohmann Film Editiors Dennis M. Hill and Sidney Levin Sound recorded by Chris McLaughlin Sound editor William A. Sawyer Original lyrics Robert Altman, Henry Gibson, Ben Raleigh, Richard Reicheg, Lily Tomlin Political campaign designer....Thomas HalPhillips David Arkin...Norman Barbara Baxley...Lady Pearl Ned Beatty...Delbert Reese Karen Black...Connie White Ronee Blakley...Barbara Jean Timothy Brown ...Tommy Brown Patti Bryant...Smokey Mountain Laurel Keith Carradine...Tom Frank Richard Baskin...Frog Geraldine Chaplin...Opal Jonnie Barnett...Himself Robert DoQui...Wade Cooley Vassar Clements...Himself Shelley Duvall...L. A. Joan Sue Barton...Herself Allen Garfield...Barnett Elliott Gould...Himself Henry Gibson...Haven Hamilton Julie Christie...Herself Scott Glenn...Private First Class Glenn Kelly Robert L. DeWeese Jr....Mr. Green Jeff Goldblum...Tricycle Man Gailard Sartain...Man at Lunch Counter Barbara Harris...Albuquerque Howard K. Smith...Himself David Hayward ...Kenny Fraiser Academy Award for Best Song: Keith Carradine, “I’m Easy” Michael Murphy...John Triplette Selected for the National Film Registry by the National Film Allan F. Nicholls...Bill Preservation Board Dave Peel...Bud Hamilton Cristina Raines...Mary ROBERT ALTMAN (20 February 1925, Kansas City, Bert Remsen...Star Missouri—20 November 2006, Los Angeles), has developed Lily Tomlin...Linnea Reese the form of interlocked narrative to a level that is frequently Gwen Welles ... Sueleen Gay copied (e.g. -

Available Videos for TRADE (Nothing Is for Sale!!) 1

Available Videos For TRADE (nothing is for sale!!) 1/2022 MOSTLY GAME SHOWS AND SITCOMS - VHS or DVD - SEE MY “WANT LIST” AFTER MY “HAVE LIST.” W/ O/C means With Original Commercials NEW EMAIL ADDRESS – [email protected] For an autographed copy of my book above, order through me at [email protected]. 1966 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS and NBC Fall Schedule Preview 1997 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS Fall Schedule Preview (not for trade) Many 60's Show Promos, mostly ABC Also, lots of Rock n Roll movies-“ROCK ROCK ROCK,” “MR. ROCK AND ROLL,” “GO JOHNNY GO,” “LET’S ROCK,” “DON’T KNOCK THE TWIST,” and more. **I ALSO COLLECT OLD 45RPM RECORDS. GOT ANY FROM THE FIFTIES & SIXTIES?** TV GUIDES & TV SITCOM COMIC BOOKS. SEE LIST OF SITCOM/TV COMIC BOOKS AT END AFTER WANT LIST. Always seeking “Dick Van Dyke Show” comic books and 1950s TV Guides. Many more. “A” ABBOTT & COSTELLO SHOW (several) (Cartoons, too) ABOUT FACES (w/o/c, Tom Kennedy, no close - that’s the SHOW with no close - Tom Kennedy, thankfully has clothes. Also 1 w/ Ben Alexander w/o/c.) ACADEMY AWARDS 1974 (***not for trade***) ACCIDENTAL FAMILY (“Making of A Vegetarian” & “Halloween’s On Us”) ACE CRAWFORD PRIVATE EYE (2 eps) ACTION FAMILY (pilot) ADAM’S RIB (2 eps - short-lived Blythe Danner/Ken Howard sitcom pilot – “Illegal Aid” and rare 4th episode “Separate Vacations” – for want list items only***) ADAM-12 (Pilot) ADDAMS FAMILY (1ST Episode, others, 2 w/o/c, DVD box set) ADVENTURE ISLAND (Aussie kid’s show) ADVENTURER ADVENTURES IN PARADISE (“Castaways”) ADVENTURES OF DANNY DEE (Kid’s Show, 30 minutes) ADVENTURES OF HIRAM HOLLIDAY (8 Episodes, 4 w/o/c “Lapidary Wheel” “Gibraltar Toad,”“ Morocco,” “Homing Pigeon,” Others without commercials - “Sea Cucumber,” “Hawaiian Hamza,” “Dancing Mouse,” & “Wrong Rembrandt”) ADVENTURES OF LUCKY PUP 1950(rare kid’s show-puppets, 15 mins) ADVENTURES OF A MODEL (Joanne Dru 1956 Desilu pilot. -

On the Auto Body, Inc

FINAL-1 Sat, Oct 14, 2017 7:52:52 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of October 21 - 27, 2017 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3 ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 10/31/17 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnetts H1artnett x 5” On the Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 run DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Emma Dumont stars 15 WATER STREET in “The Gifted” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Now that their mutant abilities have been revealed, teenage siblings must go on the lam in a new episode of “The Gifted,” airing Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 Monday. ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents Massachusetts’ First Credit Union • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents Located at 370 Highland Avenue, Salem John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks St. Jean's Credit Union • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3” With 35 years experience on the North Serving over 15,000 Members •3 A Partx 3 of your Community since 1910 Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs The LawOffice of Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Auto • Homeowners 978.739.4898 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com Business -

Click to Download

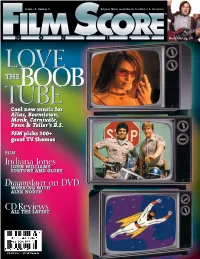

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

1968-May.Pdf

-.. -4 --,- - ANOK - mw~ AE OooWN 40_ f .A l -- -_ - _-; - I, " -, - 4--':.LL-9jL - ~·~:o~~_·r+·T~R ~ ~~~ __ - ~.,, ~~~-- L_-··-__et_r4- · ,---- 7,~ -;ami: is as Ad~,~4'f~ - rW.-. .r9 a :cr mok,~~~~~~~c. --.z-.TB 3A1aW ,5l.11 I -. -1 i" \.J . ., t ' q:i t gI~ 1wDn'' fI 1 it U 0 C IA R E TT s 20 - =l~awlaqlk j Oh b vd guideIF VOO DOO may, 1968 =·\ Transformer Wesley Mo ore Attenuator Jim Tagga rt University Insuranc Commercial Gary Blau Generator Ed "The H ick" Salzburg Agency, Inc. Screw-Up John Jurewicz BoYL5ToN ST. W5sToN Antenna Rich Rosen (oYP? PRUDENTYL CENTER) Resistor Raisa Berlin Video Valve Mike Brom berg Autonobile and Motoreycle Triode Scotly Rho( es Insutrance Ionisphere Charles Deber, Ph.D., Hs. C. Sybsystem Art Polansl :y Noise Generator Mark Mariinch Ghosts Alan Chapi nan ALL RISKS ACCEPTED FOR LIABILITY, Flicks Finder and Lavin FIRE/THEFT AND COLLISION COVERAGE Nielsen Trv Simnn-'Steve Gallant Static Harold Federow Phosphor PhosphorusS "FOR PERSONAL SERVICE, CALL ON VooDoo is published 9 times ayear(Oct. thru May, and US AT THE UNIVERSITY" in August) by the VooDoo Managing Board, 84 Massa- TELEPHONE: 536 - 9555 chusetts Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02139; en- tered as Second Class Mail at the Boston Post Office, I i , ' ;L ·r 111~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ _ Year subscription Three Dollars. Volume 51, Number 8, --Z - L-C May, 1968. Thank God. ON V. D. GUIDE'S COVER THIS WEEK ... rFF Shown on V.D. Guide's cover this week are the rising new stars Connie Linkes and Rod Fellas, hard at work on their new show, "Annie, Gotcha 'Gain" premiering &PIZZAthis week on Channel 69, Tuesdays at 8:30. -

The Films of Uwe Boll Vol. 1

THE FILMS OF UWE BOLL VOL. 1 THE VIDEO GAME MOVIES (2003-2014) MAT BRADLEY-TSCHIRGI MOON BOOKS PUBLISHING CONTENTS Foreword Introduction 1. House of the Dead 2. Alone in the Dark 3. BloodRayne 4. BloodRayne 2: Deliverance 5. In the Name of the King: A Dungeon Siege Tale 6. Postal 7. Far Cry 8. BloodRayne: The Third Reich 9. In the Name of the King 2: Two Worlds 10. Blubberella 11. In the Name of the King 3: The Last Mission Acknowledgments About the Author INTRODUCTION Video games have come a long way, baby. What started as an interactive abstract take on ping pong has morphed into a multi-billion dollar a year industry. When certain video game franchises started making oodles and oodles of money, Hollywood came a knockin' to adapt these beloved properties for the silver screen. Street Fighter, Mortal Kombat, and Resident Evil notwithstanding, audiences didn't flock to the cinema to watch their interactive favorites writ large. However, they sell pretty well on DVD and Blu-ray and tend to be made on a meager budget. Thus, video game movies continue to be released. No director has made more live-action video game feature films than Uwe Boll. Holding a PhD in Literature from The University of Siegen, Dr. Boll has shot nearly a dozen of these pictures. It should be noted his full filmography is quite varied and not just limited to video game adaptations; his other movies are often dramas with political elements and shall be covered in two more forthcoming volumes: The Films of Uwe Boll Vol. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

CBS, Rural Sitcoms, and the Image of the South, 1957-1971 Sara K

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Rube tube : CBS, rural sitcoms, and the image of the south, 1957-1971 Sara K. Eskridge Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Eskridge, Sara K., "Rube tube : CBS, rural sitcoms, and the image of the south, 1957-1971" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3154. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3154 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. RUBE TUBE: CBS, RURAL SITCOMS, AND THE IMAGE OF THE SOUTH, 1957-1971 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Sara K. Eskridge B.A., Mary Washington College, 2003 M.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2006 May 2013 Acknowledgements Many thanks to all of those who helped me envision, research, and complete this project. First of all, a thank you to the Middleton Library at Louisiana State University, where I found most of the secondary source materials for this dissertation, as well as some of the primary sources. I especially thank Joseph Nicholson, the LSU history subject librarian, who helped me with a number of specific inquiries.