1 Democracy and Protest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

55 130516 Informe Especial El Congreso Argentino.Indd

SPECIAL REPORT The Argentinian Congress: political outlook in an election year Buenos Aires, May 2013 BARCELONA BOGOTÁ BUENOS AIRES LIMA LISBOA MADRID MÉXICO PANAMÁ QUITO RIO J SÃO PAULO SANTIAGO STO DOMINGO THE ARGENTINIAN CONGRESS: POLITICAL OUTLOOK IN AN ELECTION YEAR 1. INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION 2. WHAT HAPPENED IN 2012? 3. 2013 OUTLOOK On 1st March 2013, the president of Argentina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, opened a new regular sessions’ period in the Argentinian 4. JUSTICE REFORM AND ITS Congress. POLITICAL CONSEQUENCES 5. 2013 LEGISLATIVE ELECTIONS In her message, broadcasted on national radio and television, the 6. CONCLUSIONS head of state summarized the main economic indicators of Argentina AUTHORS and how they had developed over the last 10 years of Kirchner’s LLORENTE & CUENCA administration, a timeframe she called “a won decade”. National deputies and senators, in Legislative Assembly, attended the Presidential speech after having taken part in 23 sessions in each House, which strongly contrasts with the fi gure registered in 2011, when approximately a dozen sessions were held. The central point of her speech was the announcement of the outlines of what she called “the democratization of justice”. The modifi cation of the Judicial Council, the creation of three new Courts of Cassation and the regulation of the use of precautionary measures in lawsuits against the state were, among others, the initiatives that the president promised to send to Congress for discussion. Therefore, the judicial system reform became the main political issue in the 2013 public agenda and had a noteworthy impact on all areas of Argentinian society. -

Argentine Democratic Politics in an Era of Global Economic Crisis

Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Volume 8, No. 1: 1-25 Argentine Democratic Politics in an Era of Global Economic Crisis Alejandro Bonvecchi and Javier Zelaznik Abstract This essay investigates the political and economic conditions that shaped Argentina´s response to the international economic crisis of 2008-2009 and its effects on the democratic regime. Argentina managed not only to preserve its democracy but also to improve its citizens' level of support for it during the crisis. Three factors account for these outcomes. One is the government's ability to obtain funding for its counter-cyclical policies, which enabled it to redress some of the economic and social effects of the crisis. Another factor is the government's success in presenting its statist and redistributive policy responses as a break with the past, thus recreating expectations of change to the status quo and hope for a better future. Finally, the timing of the legislative election and the coalitional dynamics of the opposition allowed the government to perform a strategic shift, which effectively reshaped the political agenda and enabled the ruling coalition to recover from an important electoral defeat by reinventing its nature. These factors enabled the incumbent government to recast the continuity of its previous policies as a novel response to the crisis, and thus rekindle the basis for a positive assessment of the democratic regime among citizens. Key words: Argentina, democracy, economic crisis, elections. The political effects of the international economic crisis of 2008-2009 in Latin America were somewhat anomalous. Contrary to the expectations born out of the experience of the Great Depression, the crisis did not weaken but strengthened public support for democracy. -

New Victories for Kirchner LADB Staff

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiSur Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 9-19-2003 New Victories for Kirchner LADB Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur Recommended Citation LADB Staff. "New Victories for Kirchner." (2003). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur/13188 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiSur by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 52610 ISSN: 1089-1560 New Victories for Kirchner by LADB Staff Category/Department: Argentina Published: 2003-09-19 With little more than 100 days in office, Argentine President Nestor Kirchner has new reasons to celebrate. He signed a deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), one day after failing to meet a payment, that most analysts saw as a coup for the president. And, his political strength has increased with the victory of candidates he endorsed in elections in several provinces and the city of Buenos Aires. Kirchner, who marked 100 days in office Sept. 1, has seemed a far cry from recent Argentine political leaders, whether on issues of IMF renegotiations, human rights, relations with the US, trade, or domestic policies. Kirchner continues to enjoy high public support. He has the most prestige of any president in recent years, and few people have much negative to say about him, said political consultant Enrique Zuleta Puceiro of the firm OPSM. In a recent OPSM poll, respondents gave Kirchner high marks for initiative, independence of criteria, and leadership, with percentages near 70%. -

“Bringing Militancy to Management”: an Approach to the Relationship

“Bringing Militancy to Management”: An Approach to the Relationship between Activism 67 “Bringing Militancy to Management”: An Approach to the Relationship between Activism and Government Employment during the Cristina Fernández de Kirchner Administration in Argentina Melina Vázquez* Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET); Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani; Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina Abstract This article explores the relationship between employment in public administration and militant commitment, which is understood as that which the actors themselves define as “militant management.” To this end, an analysis is presented of three groups created within three Argentine ministries that adopted “Kirchnerist” ideology: La graN maKro (The Great Makro), the Juventud de Obras Públicas, and the Corriente de Libertación Nacional. The article explores the conditions of possibility and principal characteristics of this activism as well as the guidelines for admission, continuing membership, and promotion – both within the groups and within government entities – and the way that this type of militancy is articulated with expert, professional and academic capital as well as the capital constituted by the militants themselves. Keywords: Activism, expert knowledge, militant careers, state. * Article received on November 22, 2013; final version approved on March 26, 2014. This article is part of a series of studies that the author is working on as a researcher at CONICET and is part of the project “Activism and the Political Commitment of Youth: A Socio-Historical Study of their Political and Activist Experiences (1969-2011)” sponsored by the National Agency for Scientific and Technological Promotion, Argentine Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation (2012-2015), of which the author is the director. -

Casaroes the First Y

LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER GLOBAL THE NEW AND AMERICA LATIN Antonella Mori Do, C. Quoditia dium hucient. Ur, P. Si pericon senatus et is aa. vivignatque prid di publici factem moltodions prem virmili LATIN AMERICA AND patus et publin tem es ius haleri effrem. Nos consultus hiliam tabem nes? Acit, eorsus, ut videferem hos morei pecur que Founded in 1934, ISPI is THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER an independent think tank alicae audampe ctatum mortanti, consint essenda chuidem Dangers and Opportunities committed to the study of se num ute es condamdit nicepes tistrei tem unum rem et international political and ductam et; nunihilin Itam medo, nondem rebus. But gra? in a Multipolar World economic dynamics. Iri consuli, ut C. me estravo cchilnem mac viri, quastrum It is the only Italian Institute re et in se in hinam dic ili poraverdin temulabem ducibun edited by Antonella Mori – and one of the very few in iquondam audactum pero, se issoltum, nequam mo et, introduction by Paolo Magri Europe – to combine research et vivigna, ad cultorum. Dum P. Sp. At fuides dermandam, activities with a significant mihilin gultum faci pro, us, unum urbit? Ublicon tem commitment to training, events, Romnit pari pest prorimis. Satquem nos ta nostratil vid and global risk analysis for pultis num, quonsuliciae nost intus verio vis cem consulicis, companies and institutions. nos intenatiam atum inventi liconsulvit, convoliis me ISPI favours an interdisciplinary and policy-oriented approach perfes confecturiae audemus, Pala quam cumus, obsent, made possible by a research quituam pesis. Am, quam nocae num et L. Ad inatisulic team of over 50 analysts and tam opubliciam achum is. -

“No Se Dejen Robar La Esperanza”

K Y M C Caso Píparo: 40.000 confirman que Ejemplares Isidro murió por De distribución Año XX • Nº6828 Entrega bajo puerta: $3,00 el tiro a Carolina gratuita Edición de 40 páginas En la noticia Recargo Interior: $0,50 La Plata, martes 26 de marzo de 2013 - PAG. 20 “No se dejen robar la esperanza” La frase del Papa Francisco está inspirando a muchos de los que organizan -para el 18 de abril- una masiva movilización en todo el país. Reclamos por la inflación, la crisis Camino hacia el educativa, la inseguridad y los ataques al periodismo independiente #18A - PAGS. 3 A 5 Provincia: se viene un paro docente de 72 horas y denuncian intento destituyente - PAG. 7 Barsottini, el Desde las 17, ídolo tripero Argentina visita que se ilusiona a Bolivia con el ascenso - EL C LASICO - EL C LASICO La Plata, martes 26 2 Diario en la noticia de marzo de 2013 A los lectores Más de 172 mil Los K no se hacen cargo de la casos de doble Estando a una altura de mes donde gran parte de los trabajadores están con las mo- afiliación nedas justas, y teniendo en cuenta que el país atraviesa por momentos políticos y falta de reparto de fondos La Junta Electoral económicos cruciales, el diario Hoy vuelve a bonaerense detectó más de realizar un enorme esfuerzo editorial dis- 172 mil casos de personas tribuyendo –durante la presente jornada- 40 o hay ninguna guerra con- con doble afiliación a par- mil ejemplares gratuitos en La Plata, Berisso, “N tra (Daniel) Scioli", dijo tidos políticos provinciales y Ensenada, Quilmes y Berazategui. -

Argentina: the National Congress Under the Gaze of a Lame Duck Kirchnerism?

SPECIAL REPORT Argentina: The National Congress under the gaze of a lame duck Kirchnerism? Buenos Aires, April 2015 BARCELONA BOGOTÁ BUENOS AIRES LIMA LISBOA MADRID MÉXICO PANAMÁ QUITO RIO J SÃO PAULO SANTIAGO STO DOMINGO ARGENTINA: THE NATIONAL CONGRESS UNDER THE GAZE OF A LAME DUCK KIRCHNERISM? 1. INTRODUCTION In 2015 we could witness the end of a political process called 1. INTRODUCTION “Kirchnerism”, which has governed Argentine for 12 years in a 2. KIRCHNERISM AND LEGISLATIVE row, and which was started by Nestor Kirchner in 2003 and then POWER continued by his wife Cristina Fernández de Kirchner for two 3. THE CONGRESS IN 2014 more terms. 4. EXPECTATIONS FOR 2015 5. ¿AND WHAT ABOUT 2016? This year will also be a period deeply influenced by electoral 6. UNANSWERED QUESTIONS politics. The Argentinian Constitution prevents a new reelection of the current President. This means the President is living her last year in office and December the 10th 2015 it will be the last AUTHOR day of her term. We could have a second round on the elections which are always formed by the primary elections and the first round: this second round is known as the Ballotage or second round1. To this possible second round we need to add the provincial and municipal elections. In the most populated districts the elections will be divided (Federal capital, Cordoba, Mendoza and Santa Fe). Apart from the new President, new seats for the National Congress will also be elected. So far, the governing party rules the legislative agenda and is in possession of a majority of one's own although with a lower number of parliamentarians. -

Briefing European Parliamentary Research Service

At a glance September 2015 Argentina: Political parties and the EU Argentina's presidential elections are scheduled for October 2015 and, according to the country's Constitution, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner is not entitled to run for a third consecutive term. As regards alternative candidates, the political landscape remains polarised after the primary elections. Argentina has a multi-party political system; however, election results demonstrate that it is, in practical terms, bipartisan. The Peronists, represented by the Justicialist Party (PJ), and the radicals, represented by the Civic Radical Union (UCR), effectively alternate in power. Argentinian political decision-making is opaque, complex and volatile. Parties play for power in changing coalitions, splits and mergers, which lead to a constantly changing political landscape of alliances. Political and Electoral System The Constitution of Argentina dates back to 1853. It remained in force under the various military regimes, with the exception of the Peronist constitutional period between 1949 and 1956. Over the years, it has been subject to a number of amendments, the most important in 1953, and recently in 1994. Argentina is a federal republic with division of powers. The executive is currently represented by the President, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, from the centre-left Peronist faction, Front For Victory (FPV), which belongs to the Justicialist Party. The President is elected for a four-year term with the possibility of being re-elected for only one consecutive term. Elections take place in two rounds. To be directly elected in the first round, the candidate needs to obtain 45% of the votes cast, or 40% and be 11% ahead of the second candidate. -

Argentina and the Falkland Islands

Argentina and the Falkland Islands Standard Note: SN/IA/5602 Last updated: 27 January 2012 Author: Vaughne Miller Section IADS This Note looks briefly at the government in Argentina under Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who has pursued the Argentinean claim to sovereignty of the Falkland Islands as a constitutional mandate. The arguments on the Argentinean and British sides have not changed with a change of government, while recent developments such as changes to the way in which fishing licences are issued and oil exploration around the Falklands, are continuing to affect bilateral relations. The Falklands/Malvinas are regularly debated at the United Nations Committee on Decolonization, at which a resolution is adopted calling on the two sides to talk about the issues. Successive UK governments have insisted that it is the Falkland Islanders themselves who have the right to decide on their destiny. Argentina maintains that the UN principle of the right to self-determination does not apply in the case of the Falklanders. Both the UK and Argentina accuse each other of colonialism. See Standard Note 6201 for information on the defence of the Falklands. Contents 1 The Argentinean Government 2 1.1 Néstor Kirchner Government 2 1.2 Cristina Fernández de Kirchner Government 4 2 UK relations with Argentina 6 3 The Falkland Islands 8 3.1 UK Government’s position on Falklands sovereignty 8 3.2 Argentinean views on sovereignty of the Malvinas 10 This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. -

The Languages of the Arab Revolutions Abdou Filali-Ansary the Freedom House Survey for 2011 Arch Puddington

April 2012, Volume 23, Number 2 $12.00 The Languages of the Arab Revolutions Abdou Filali-Ansary The Freedom House Survey for 2011 Arch Puddington Tunisia’s Transition and the Twin Tolerations Alfred Stepan Forrest D. Colburn & Arturo Cruz S. on Nicaragua Ernesto Calvo & M. Victoria Murillo on Argentina’s Elections Arthur Goldsmith on “Bottom-Billion” Elections Ashutosh Varshney on “State-Nations” Tsveta Petrova on Polish Democracy Promotion Democracy and the State in Southeast Asia Thitinan Pongsudhirak Martin Gainsborough Dan Slater Donald K. Emmerson ArgentinA: the persistence of peronism Ernesto Calvo and M. Victoria Murillo Ernesto Calvo is associate professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland–College Park. M. Victoria Murillo is profes- sor of political science and international affairs at Columbia Univer- sity and the author of Political Competition, Partisanship, and Policy- making in Latin America (2009). On 23 October 2011, Argentina’s Peronist president Cristina Fernán- dez de Kirchner of the Justicialist Party (PJ) overcame a bumpy first term and comfortably won reelection. She garnered an outright major- ity of 54.1 percent of the popular vote in the first round, besting her 2007 showing by roughly 9 percentage points and avoiding a runoff. Although most observers had expected her to win, the sweeping scale of her victory exceeded the expectations of both her administration and the fragmented opposition. In the most lopsided presidential result since 1928,1 she carried 23 of Argentina’s 24 provinces while her leading rival Hermes Binner, the Socialist governor of Santa Fe Province, collected only 16.8 percent of the national vote. -

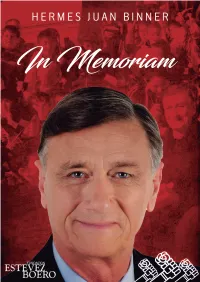

Hermes Binner in Memori

SUMARIO Un socialista más, pero no uno cualquiera Por MARIANO SCHUSTER Y FERNANDO MANUEL SUAREZ ............................................................. 7 Lo que brilla con luz propia nadie lo puede apagar Por GASTÓN D. BOZZANO ......................................................................................................................... 13 El padre de la criatura fue un solista que le dio vuelo propio al socialismo local Por MAURICIO MARONNA ......................................................................................................................... 17 Binner, el médico que inventó la marca Rosario Por LUIS BASTÚS ......................................................................................................................................... 20 Pablo Javkin recordó a Hermes Binner: Rosario ya te extraña y te honra Nota en el diario EL CIUDADANO ............................................................................................................ 22 Hermes Binner, el hombre que no se dejaba apurar por el tiempo Por DAVID NARCISO ................................................................................................................................... 24 Un buen hombre, un mejor amigo Por THOMAS ABRAHAM ............................................................................................................................. 29 Un dirigente que funcionó en modo política 30 años Por DANIEL LEÑINI .................................................................................................................................... -

Pension System Reforms in Argentina

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Digital Archive at Oslo and Akershus University College Silvia I. Reyna Rickert ________________________________ Pension System Reforms in Argentina Why the U-Turn? Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences Abstract The 2008 Argentine pension reform represented a new change of paradigm in the country’s pension policy. It encompassed the elimination of the fully funded, defined contribution (DC), private tier of the so-called Integrated Retirement and Pensions System (SIJP) – a two- tiered arrangement implemented in 1994 and inspired by the World Bank’s recommendations contained in the work Averting the Old Age Crisis (World Bank 1994). And the shift back to a publicly managed, single-tiered pension system provided in a pay-as-you-go defined benefit (PAYG-DB) basis: the Argentine Integrated Retirement System (SIPA). In order to finally explain these events, in this thesis I present a detailed account of the events that took place in 2008, divided into six chapters. The first chapter introduces the topic, its background and the research question: Why did Argentina change its pension system back to a one-tiered, pay as you go DB system in 2008? The second explains the appropriateness of the research strategy and the design chosen for this study. In the third chapter, the reader is introduced to the events under analysis and the possible explanations or “suspects” to be explored upon. The fourth chapter provides the framework and settings to understand Argentina’s policy making process.