' Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Searching for Superwomen: Female Fans and Their Behavior

SEARCHING FOR SUPERWOMEN: FEMALE FANS AND THEIR BEHAVIOR _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by SOPHIA LAURIELLO Dr. Cynthia Frisby, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2017 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled SEARCHING FOR SUPERWOMEN: FEMALE FANS AND THEIR BEHAVIOR presented by Sophia Lauriello, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Cynthia Frisby Professor Amanda Hinnant Professor Lynda Kraxberger Professor Brad Desnoyer FEMALE FANS AND THEIR BEHAVIOR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge Dr. Cynthia Frisby for all of her work and support in helping this thesis go from an idea to a finished paper. Thank you to everyone on my committee who was as enthused about reading about comic books as I am. A huge acknowledgement to the staff of Star Clipper who not only were extremely kind and allowed me to use their game room for my research, but who also introduced me to comic book fandom in the first place. A thank you to Lauren Puckett for moderating the focus groups. Finally, I cannot thank my parents enough for not only supporting dropping out of the workforce to return to school, but for letting me (and my cat!) move back home for the last year and a half. Congratulations, you finally have your empty nest. ii FEMALE FANS AND THEIR BEHAVIOR TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... -

Koronaviruspandemian Vaikutus Elektroniseen Urheiluun

Koronaviruspandemian vaikutus elektroniseen urheiluun Rami Waly ja Tuomo Tammela 2021 Laurea Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu Koronaviruspandemian vaikutus elektroniseen urheiluun Rami Waly ja Tuomo Tammela Tietojenkäsittely Opinnäytetyö Huhtikuu 2021 Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu Tiivistelmä Tietojenkäsittely koulutusohjelma Tradenomi (AMK) Rami Waly, Tuomo Tammela Koronaviruspandemian vaikutus elektroniseen urheiluun Vuosi 2021 Sivumäärä 48 Opinnäytetyön tavoitteena on selvittää, kuinka koronaviruspandemia on vaikuttanut elektro- niseen urheiluun. Opinnäytetyössä käydään läpi mitä toimia elektronisen urheilun organisaa- tiot ja tapahtumien ylläpitäjät ovat ottaneet siirtääkseen toimintaansa LAN-pelaamisesta verkkopelaamiseen. Lisäksi opinnäytetyöstä selviää, millä tavoin e-urheilun tapahtumien jär- jestäminen on pyritty turvaamaan pandemian aikana. Opinnäytetyössä tutkittiin myös eri kil- pailullisten videopelien lajeja sekä elektronisen urheilun organisaatioita. Elektronisen urheilun kysynnän ja joukkueiden kilpailullisen hengen kasvaessa seuraajat jää- vät miettimään, kuinka pandemian vaikutukset muuttavat elektronista urheilua tulevina vuo- sina. E-urheilun tapahtumat ovat yleisesti toimineet paikallisesti, mutta turnauksia on aiem- min myös pidetty verkon kautta. Tämänhetkinen koronaviruspandemia pakotti kaikki elektro- nisen urheiluun liittyvät osapuolet sopeutumaan nopeasti uuteen tilanteeseen, sekä arvioi- maan uudelleen kaikki mahdolliset turvatoimet katsojien, pelaajien ja työntekijöiden vuoksi. Opinnäytetyössä tutkitaan myös latenssin -

Busiek • Dewey • Scharf • Farrell

BUSIEK • DEWEY • SCHARF • FARRELL BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! RATED RATED 0 0 5 1 1 $3.99 5 US T+ 7 5 9 6 0 6 2 0 0 0 8 5 NAMOR THE SUB-MARINER--SON OF AN ATLANTEAN PRINCESS FROM THE DEPTHS OF THE OCEAN AND A HUMAN SAILOR. BORN A MUTANT, WITH THE POWERS OF FLIGHT, INCREDIBLE STRENGTH AND DURABILITY. NOW THE RULER OF THE UNDERWATER EMPIRE OF ATLANTIS, HE HAS BEEN BOTH FRIEND AND FOE TO HUMANITY. CHAPTER 5 THE BREAKING WAVE OLDER THAN MEMORY AND IMPRISONED AT THE EDGE OF THE GALAXY FOR MILLENNIA, KNULL, THE GOD-KING OF THE SYMBIOTES, HAS BEEN FREED AND LED A HORDE OF MORE THAN ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND DRAGONS ACROSS THE COSMOS, WITH A TRAIL OF DEATH AND DESTRUCTION IN THEIR WAKE. THE KING IN BLACK HAS ARRIVED ON EARTH. BUT THE FIGHT TO STOP KNULL REACHES FAR INTO THE PAST, WHEN A YOUNG NAMOR ADMIRED THE GROUP OF ATLANTEAN WARRIORS KNOWN AS THE SWIFT TIDE. NAMOR, DORMA AND ATTUMA SET OUT ALONGSIDE THE SWIFT TIDE ON A MISSION TO RETRIEVE THE UNFORGOTTEN STONE, A POWERFUL MAGICAL RELIC. WHEN THE STONE RELEASED A BLAST OF DARK ELDRITCH ENERGY, THE SWIFT TIDE WAS CORRUPTED, TRANSFORMING INTO THE VICIOUS, MURDEROUS BLACK TIDE. NAMOR AND HIS ALLIES PURSUED THE WARRIORS AS THEY RAMPAGED ACROSS THE OCEAN. WITH THE BLACK TIDE NOW AT THE GATES OF ATLANTIS ITSELF, DORMA’S PET FISH, AMBROSE, REAPPEARED IN MONSTROUS, MUTATED FORM BUT WITH AN UNEXPECTED GIFT FOR NAMOR AND HIS ALLIES: THE UNFORGOTTEN STONE! KURT BUSIEK WRITER // BENJAMIN DEWEY ARTIST JONAS SCHARF PRESENT DAY SEQUENCE ARTIST TRÍONA FARRELL COLOR ARTIST KING IN BLACK: NAMOR No. -

Ottawa (Ontario, Canada) SELLER MANAGED Reseller Online Auction - Starwood Road

09/28/21 11:23:31 Ottawa (Ontario, Canada) SELLER MANAGED Reseller Online Auction - Starwood Road Auction Opens: Mon, Jun 29 5:00pm ET Auction Closes: Wed, Jul 8 7:30pm ET Lot Title Lot Title 0001 Gordie Howe Autographed Photo Framed with 0020 1999 Upper Deck Wayne Gretzky 22 karat Certificate of Authenticity A Gold Cards in original holder A 0002 1968 Marvel Comic Nick Fury Agent of 0021 1997-98 Kraft Hockey Card Set in Original S.H.I.E.L.D. # 1 Issue A Album A 0003 Box lot of 350+ sports cards hockey football 0022 1994 Upper Deck hockey Card Wax Box 24 baseball golf 1970's to Current A Packs 0004 1982 Empire Strikes Back Movie Poster A Maurice Richard Picture on box 1956-57 Parkhurst A 0005 Lot of 16 Older Rock Albums Zeppelin, Queen, Genesis, King Crimson A 0023 1992 Sporting News Conlin Collection Wax Box 36 Packs Vintage Baseball Players Babe 0006 1950's Original Davy Crockett Metal Thermos Ruth, Ty Cobb etc. A by Holtemp A 0024 1948 Maurice Richard Original Playing Card 0007 1960's Jello Automobile Coin Lot of 200 with Montreal Canadiens A Original Plastic Carousel A 0025 Bobby Orr Autographed Hockey Card Blue 0008 Lot of 650 + Red Rose Tea Cards from the Sharpie A 1960's A 0026 Mini Louisville slugger Baseball Bat from 0009 1983-84 OPC Hockey EMPTY Wax Pack Cooperstown New York A Display Box A 0027 1969 Marvel Comic The Incredible Hulk # 118 0010 1993 OPC Hockey Card Wax Box with A Original Seal A 0028 1966 Marvel Comic Fantastic Four # 58 A 0011 1992 Future Trends 1976 Canada Cup Hockey Card Wax Box 36 Packs with Original Seal -

Selznick, Brian Boy of a Thousand Faces Juv

GRAPHIC NOVELS- PRESCHOOL, ELEMENTARY& MIDDLE SCHOOL compiled by Sheila Kirven HYBRID Preschool Alborough, Jez Yes Juv.A3397y Cordell, Matthew Wolf in the snow Juv.C7946w Haughton, Chris Shh! We have a plan Juv. H3717s McDonald, Ross Bad Baby Juv.M13575b (Jack has a new baby sister) Reynolds, Aaron Creepy Carrots Juv.R462c Rex, Adam Pssst! Juv.R4552p Rocco, John Blackout Juv.R6715b Willems, Mo That is not a good idea! Juv.W699t Vere, Ed Getaway Juv.V4893g Elementary Buzzeo, Toni One cool friend Juv. B9928o Chin, Jason Island: A Story of the Galapagos Juv.508.86.C539i Craft, Jerry Big Picture: Juv.C8856m What you need to succeed! Dauvillier, Loie hidden Juv.D2448 (A young French girl is hidden away during the Holocaust in France) DiCamilio, Kate Flora & Ulysses: Juv. D545f The Illuminated Adventures (Rescuing a squirrel after an accident involving a vacuum cleaner, comic-reading cynic Flora Belle Buckman is astonished when the squirrel, Ulysses, demonstrates astonishing powers of strength and flight after being revived.) Gaiman, Neil The day I swapped my Dad for two Juv.G141di goldfish Holub, Joan Little Red Writing Juv.H7589L (A brave little pencil attempting to write a story with a basket of parts of speech outwits the Wolf 3000 pencil sharpener and saves Principal Granny.) Lane, Adam J.B. Stop Thief Juv. L2652s Law, Felicia & Castaway Code: Sequencing in Action Juv.L4152c Way, Steve Law, Felicia & Crocodile teeth: Geometric Shapes Juv.L4152ct Way, Steve in Action Law, Felicia & Mirage in the Mist: Measurement Juv.L4152ct Way, Steve in Action Law, Felicia & Mystery of Nine: Number Place Juv.L4152mn Way, Steve and Value in Action Law, Felicia & Storm at Sea: Sorting, Mapping and Juv.L4152ct Way, Steve Grids in Action sdk 6/08 rev. -

Is Battleworld! Charles Xavier Is Dead, and to The

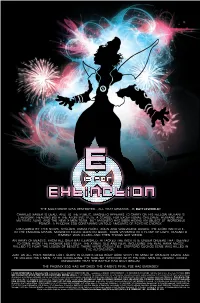

THE MULTIVERSE WAS DESTROYED…ALL THAT REMAINS…IS BATTLEWORLD! CHARLES XAVIER IS DEAD, AND TO THE PUBLIC, MAGNETO APPEARS TO CARRY ON HIS FELLOW MUTANT’S LIFEWORK: HEADING BOTH THE ATOM INSTITUTE--A SCHOOL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN, HUMANS AND MUTANTS ALIKE--AND THE NEW X-MEN TEAM. BUT MAGNETO HAS BEEN HIDING AN OBJECT OF INCREDIBLE POWER: A PHOENIX EGG CONTAINING UNTOLD AMOUNTS OF PSYCHIC ENERGY. DISTURBED BY THIS NEWS, CYCLOPS, EMMA FROST, XORN AND WOLVERINE RAIDED THE ATOM INSTITUTE. IN THE ENSUING CHAOS, MAGNETO KILLED QUENTIN QUIRE, XORN VANISHED IN A FLASH OF LIGHT, MAGNETO HIMSELF WAS KILLED--AND THEN THINGS GOT WEIRD. AN ARMY OF BEASTS, FROM ALL OVER BATTLEWORLD, ATTACKED THE INSTITUTE UNDER ORDERS THAT SEEMED TO COME FROM THE PHOENIX EGG ITSELF. THE X-MEN, OLD AND NEW, INCLUDING THE REAL HANK McCOY, RALLIED TO FIGHT THE LEGION OF BEASTS. THERE WERE CASUALTIES. STEPFORD CUCKOO ESME WAS KILLED IN THE ALTERCATION. JUST AS ALL HOPE SEEMED LOST, QUENTIN QUIRE’S DEAD BODY ROSE WITH THE MIND OF CHARLES XAVIER AND HE RALLIED HIS X-MEN. AFTER STERILIZING THE SUBLIME INFECTION WITH HIS VAST MENTAL POWER, XAVIER ANNOUNCED THAT THE BATTLE HAD ONLY BEGUN! THE PHOENIX EGG HAS HATCHED! THE X-MEN’S FINAL FOE HAS EMERGED! E IS FOR EXTINCTION No. 4, November 2015. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2015 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. -

Azazel Historically, the Word Azazel Is an Idea and Rarely an Incarnate Demon

Azazel Historically, the word azazel is an idea and rarely an incarnate demon. Figure 1 Possible sigil of Azazel. Modern writings use the sigil for the planet Saturn as well. Vayikra (Leviticus) The earliest known mention of the word Azazel in Jewish texts appears in the late seventh century B.C. which is the third of the five books of the Torah. To modern American ( וַיִּקְרָ א ) book called the Vayikra Christians, this books is Leviticus because of its discussion of the Levites. In Leviticus 16, two goats are placed before the temple for selection in an offering. A lot is cast. One Goat is then sacrificed to Yahweh and the other goats is said to outwardly bear all the sends of those making the sacrifice. The text The general translation .( לַעֲזָאזֵל ) specifically says one goat was chosen for Yahweh and the for Az azel of the words is “absolute removal.” Another set of Hebrew scholars translate Azazel in old Hebrew translates as "az" (strong/rough) and "el" (strong/God). The azazel goat, often called the scapegoat then is taken away. A number of scholars have concluded that “azazel” refers to a series of mountains near Jerusalem with steep cliffs. Fragmentary records suggest that bizarre Yahweh ritual was carried out on the goat. According to research, a red rope was tied to the goat and to an altar next to jagged cliff. The goat is pushed over the cliff’s edge and torn to pieces by the cliff walls as it falls. The bottom of the cliff was a desert that was considered the realm of the “se'irim” class of demons. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Mystique Ultimate Collection Free

FREE MYSTIQUE ULTIMATE COLLECTION PDF Sean McKeever,Manuel Garcia | 264 pages | 06 Jul 2011 | Marvel Comics | 9780785155218 | English | New York, United States Mystique by Brian K. Vaughan: Ultimate Collection - Comics by comiXology: Web UK The series is a collection of special edition hardback graphic novelcollecting all the parts in a story-arc for one of Marvel 's best known superheroes, often a fan-favourite or "important" story from Marvel comics lore. The series proved so successful for publisher Hachette Partworks that they launched a Mystique Ultimate Collection series of fortnightly graphic novel hardbacks entitled Marvel's Mightiest Heroes Graphic Novel Collection and a third non-Marvel series of Mystique Ultimate Collection fortnightly graphic novel hardbacks entitled Judge Dredd: The Mega Collectiona fourth series of fortnightly graphic novel hardbacks called Transformers: The Definitive G1 Collection featuring Generation One strips from Marvel US and UK, Dreamwave and IDW and a fifth series of 80 fortnightly graphic novel hardbacks entitled AD: The Ultimate Collection. In Februaryit was announced that the collection would be re-released with alternative numbering. As well as the comic strip, each book features an introduction to the book, information on the character, writer and artist plus some of the artist's draft board sketches. In Aprila flyer accompanying Issue 62 revealed the artwork by Dell'Otto had been extended to cover volumes rather than the original Each issue number of the collection Mystique Ultimate Collection not the same as the books volume number e. Issue 1 was launched twice in the UK. Early subscribers to issue 1 volume 21 may have received an edition with a different spine from those that subscribed to the subsequent launch. -

Generation X: Workplace Issues with Today’S Emerging Workforce

Generation X: Workplace Issues with Today’s Emerging Workforce Terry A. Sanders Abstract Generation X, those persons born between 1961 and 1981, are the emerging workforce of the 1990's and beyond. This generation is the first to be born into a world where both parents are working to make ends meet, Corporate America is downsizing to work "smarter", and the world is a tumultuous place to exist. The intricacies of this generation’s upbringing have contributed to the dichotomies that make the generation unique. They exhibit an air of independence while seeking constant input as to their work product; they covet the team approach to problem solving while relishing their time away to escape and ‘do nothing’ and they are easily bored and want to change tasks while wanting to be a part of the future of their workplace. The situation remains that this is the generation that is poised to take America into the 21st. Century. Our role is to blend our workplace ideology with the Generation X philosophy of life, a task that is as interesting as any journey that America’s workplace has endeavored to go. Introduction The management and leadership of a workplace is a formidable task. Personnel, with their specific needs and expectations are neatly balanced with the needs and expectations of an organization that provides a service or expects a profit. What happens when the emerging workforce does not ‘fit’ into the existing paradigms of a corporation or governmental entity? Can you find another workforce; can the emerging workforce be ‘changed’ by placing them along side the existing workforce with the hope they will pattern their concepts to the existing ones? Generation X, the emerging workforce of the 90's is pushing the envelope of workplace structure as they exercise their concepts of how things are done. -

Aexodusftwhiteoutrrmy

X-Men Villains - Free Printable Wordsearch AEXODUSFTWHITEO UTRRM YNRIPTIDEYLUEA NVDOKX GUIVESSELWANROU LETTE IJGTMPKIUNUSCI ONEOUM SMHPSADVANISHER RSWPD GMOTTHSEDKENMKZU EZXJ PAGJRSBTHOEZTOA DZEYQ NIZKOEMQEDARKBE ASTSK AXLABNKZMROREAP ERYPE WZYHEYPUUCMVSEL BYUQP QOKKEAIDLAPIEQ NKBJNF AZCYPKPPCAHCNET EMPOL MSGYAAEMBSNATDFR DNHF PBDJBFRGXEMGBI AOLYED SPOORELGLAONATV IXMWU VIRNWBRIFPLBST UXRBBR IBFOEVTPUCQEBHH OXJAG BFKEGSYLKERHAWL RIAKT OOMFEUZTCIXFJG MNMVEF LUMPJHETFJYKZC DTQGBC KULAN GATH ROULETTE VESSEL SPOOR MASTERMIND VANISHER D KEN PIPER PESTILENCE SENYAKA REESE TOAD DARK BEAST RIPTIDE CYBER LUPO UNUSCIONE EXODUS TEMPO MOJO FIRESTAR STROBE SELBY XORN WHITEOUT REAPER ROGUE GAZA FOXBAT AHAB Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. Use freely for any use, please give a link or credit if you do. X-Men Villains - Free Printable Wordsearch GXOFATALELRNMHU NWVIX LSAURONFLETHARC LIGHT KMWQBQMADEATHBIR DLNX XFRIGBWVFSROGAU NTLET FNCQLEGMTVFENRI STZIZ DUBANDALBRIWAHL WNUWA ECEOLLSYVRJNRA MRODMH MYTGDLAIKFAHDWO RMOSO HSIEOCIADATIWA XICQGY FQBPETMSBEBBNAL SNICU HEGDOGIETXBIEC AOTPKJ JVSAAPKMTOOFCLH ROTRG EMEMFJMMETWHEAEI QDAB TDRUQWWATSOBMVTPL MKH SLAPGPLFMTHVQJP SDDOG TUFBKCURUMMAWSSQ EHAO RPINQTSOXJOHDD JCJYSW EANEILQSPJAMIO LUJNEV ATAQEPOTYADKAKWC AIMC MPTXTOANMTSIMXG HTSMA BRAINCHILD SERAFINA VERTIGO MAGMA TIMESHADOW GAUNTLET BEDLAM SKIDS EMMA FROST CALLISTO SAURON DECAY STONEWALL ARCLIGHT FATALE FUEGO DEATHBIRD WILDSIDE RAMROD LUPA JETSTREAM MAMMOMAX KRAKOA HANS VINDALOO BELASCO FENRIS NUWA CATSEYE WORM Free Printable Wordsearch from -

X-Men/Avengers: Onslaught Vol

X-MEN/AVENGERS: ONSLAUGHT VOL. 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jeph Loeb | 448 pages | 29 Oct 2020 | Marvel Comics | 9781302923990 | English | New York, United States X-men/avengers: Onslaught Vol. 2 PDF Book In July during a revamp of the X-Men franchise, its title changed to New X-Men , featuring an ambigram logo issue X-Men: Legacy initially followed the Professor's presumed road to recovery as well as the encounters he faced, such as a battle with the mutant Exodus on the psychic plane [12] and discoveries about his past that include Mr. Comic book series. Log in Sign up. This was particularly unique during the late s when most X-Men titles frequently had story arcs that were several issues long. Iron Boy, Quicksilver, Black Panther and Hank Pym are making their way through the sewers looking for safety at the Wakanda embassy as the Sentinels continue to attack New York city above. This listing has ended. Cancel Update. Similar sponsored items Feedback on our suggestions - Similar sponsored items. And the goblin faces his greatest enemy - his self-esteem! To this end he got the assistance of Hellfire Club's leader Sebastian Shaw and Nate's old nemesis Holocaust , [12] however Holocaust was soon defeated. See details. It's the final battle that will change the landscape of the Marvel Universe! Onslaught's threat to the world became apparent when the heroes noticed that the creature used Franklin's powers to create a second sun that was drawing closer to the Earth, threatening to wipe out all life upon its approach.