Rifaximin (XIFAXAN)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antibiotic Treatment in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Rifaximin, a New Possible Approach

European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 1999; 3: 27-30 Review – Antibiotic treatment in inflammatory bowel disease: rifaximin, a new possible approach P. GIONCHETTI, F. RIZZELLO, A. VENTURI, F. UGOLINI*, M. ROSSI**, P. BRIGIDI**, R. JOHANSSON, A. FERRIERI***, G. POGGIOLI*, M. CAMPIERI Clinica Medica I, Nuove Patologie, Bologna University (Italy) *Istituto di Clinica Chirurgica II, Bologna University (Italy) **Dipartimento di Scienze Farmaceutiche, Bologna University (Italy) ***Direzione Medica Alfa Wassermann, Bologna (Italy) Abstract. – The etiology of inflammatory ported the presence of a breakdown of toler- disease is still unknown, but a body of evidence ance to the normal commensal intestinal flora from clinical and experimental observation indi- in active IBD2-3. Reduction of microflora by cates a role for intestinal microflora in the pathogenesis of this disease. Reduction of mi- antibiotics, bowel rest and fecal diversion de- croflora using antibiotics, bowel rest and fecal creases inflammatory activity in Crohn’s dis- diversion decreases activity in Crohn’s disease ease and to a lesser extent in ulcerative colitis and in ulcerative colitis. Several trials have been (UC). The pathogenetic role of intestinal mi- carried out on the use of antibiotic treatment in croflora is further suggested by the observa- patients with active ulcerative colitis with con- tion that experimental colitis, in germ-free or trasting results. A number of trials have been antibiotic treated animals, is less severe com- carried out using Rifaximin, a non-absorbable broad-spectrum antibiotic, confirming the ab- pared to that inducible in normal animals or sence of systemic bioavalaibility of the drug at times is not inducible at all. -

FDA Warns About an Increased Risk of Serious Pancreatitis with Irritable Bowel Drug Viberzi (Eluxadoline) in Patients Without a Gallbladder

FDA warns about an increased risk of serious pancreatitis with irritable bowel drug Viberzi (eluxadoline) in patients without a gallbladder Safety Announcement [03-15-2017] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is warning that Viberzi (eluxadoline), a medicine used to treat irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D), should not be used in patients who do not have a gallbladder. An FDA review found these patients have an increased risk of developing serious pancreatitis that could result in hospitalization or death. Pancreatitis may be caused by spasm of a certain digestive system muscle in the small intestine. As a result, we are working with the Viberzi manufacturer, Allergan, to address these safety concerns. Patients should talk to your health care professional about how to control your symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D), particularly if you do not have a gallbladder. The gallbladder is an organ that stores bile, one of the body’s digestive juices that helps in the digestion of fat. Stop taking Viberzi right away and get emergency medical care if you develop new or worsening stomach-area or abdomen pain, or pain in the upper right side of your stomach-area or abdomen that may move to your back or shoulder. This pain may occur with nausea and vomiting. These may be symptoms of pancreatitis, an inflammation of the pancreas, an organ important in digestion; or spasm of the sphincter of Oddi, a muscular valve in the small intestine that controls the flow of digestive juices to the gut. Health care professionals should not prescribe Viberzi in patients who do not have a gallbladder and should consider alternative treatment options in these patients. -

Formulary Additions

JUNE 2016 FORMULARY ADDITIONS MELOXICAM (MOBIC®) Rationale for Addition: Meloxicam is a once daily NSAID used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Meloxicam will provide another oral NSAID option to Celecoxib for patients who are being discharged home and whose insurance does not cover celecoxib. Adverse Effects: abdominal pain, diarrhea, dyspepsia, flatulence, nausea, edema, influenza-like symptoms, dizziness, headache, rash Contraindications: peri-operative pain in setting of coronary artery bypass graft surgery Drug Interactions: other NSAIDS, antiplatelet agents, calcium polysterene sulfonate, cyclosporine, digoxin, lithium, methotrexate, vancomycin, vitamin K antagonist, corticosteroids Dosage & Administration: meloxicam 7.5 mg PO daily, some patients my experience some benefit by increasing to 15 mg PO daily Renal Impairment: not recommended in patients with renal function ≤ 20 mL/min Dosage Form & Cost: meloxicam 7.5 mg tablet $0.02/day meloxicam 15 mg $0.03/day IVABRADINE (CORLANOR®) *Restrictions*: restricted to cardiology only for initiation of therapy Rationale for Addition: Ivabradine blocks the funny current leading to a reduction in heart rate at the sinoatrial node. Ivabradine is indicated to reduce the risk of hospitalization for worsening heart failure in patients with stable symptomatic chronic heart failure with LVEF ≤ 35% who are in sinus rhythm with resting heart rate (HR) ≥ 70 beats per minute and either on maximally tolerated doses of β-blockers or have a contraindication to β-blockers. -

(Or) Aravind Doki

Available Online through www.ijpbs.com (or) www.ijpbsonline.com IJPBS |Volume 3| Issue 3 |JUL-SEP|2013|152-161 Research Article Pharmaceutical Sciences METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF RP-HPLC METHOD FOR SIMULTANEOUS ESTIMATION OF CLIDINIUM BROMIDE, CHLORDIAZEPOXIDE AND DICYCLOMINE HYDROCHLORIDE IN BULK AND COMBINED TABLET DOSAGE FORMS Aravind.Doki* and Kamarapu.SK Department of Pharmaceutical Analysis, Sri Shivani College Of Pharmacy, Mulugu Road, Warangal, Andrapradesh, India, 506001. *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The study describes method development and subsequent validation of RP-HPLC method for simultaneous estimation of Clidinium bromide (CDB), Chlordiazepoxide (CDZ) and Dicyclomine hydrochloride (DICY) in bulk and combined tablet dosage forms. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Kromasil C18 (250 mm × 4.6 mm id, 5µm) column using a mobile phase ratio consisting of (40:30:30) Methanol: Acetonitrile: Potassium di hydrogen phosphate buffer (0.05M, PH 4.0 adjusting with 0.5% Ortho phosphoric acid) at flow rate 1.0 ml/min. The detection wavelength is 270 nm. The retention times of Clidinium bromide, Chlordiazepoxide and Dicyclomine hydrochloride were found to be 7.457 min, 4.400 min and 3.397 min respectively. The developed method was validated as per ICH guidelines using the parameters such as accuracy, precision, linearity, LOD, LOQ, ruggedness and robustness. The developed and validated method was successfully used for the quantitative analysis of Clidinium bromide, Chlordiazepoxide and Dicyclomine hydrochloride in bulk and combined tablet dosage forms. KEY WORDS Clidinium bromide, Chlordiazepoxide and Dicyclomine hydrochloride, Normaxin tablet dosage forms, HPLC, Method validation. INTRODUCTION hydrochloride (1, 1-bicyclohexyl-1-carboxilicacid-2- Clidinium bromide (3-[(2-hydroxy-2, [diethyl amino] ethyl ester) is an anticholinergic drug 2diphenylacetyl)-oxy]-1-methyl-1-azoniabicylo- (tertiary amine). -

Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor

mAChR Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor mAChRs (muscarinic acetylcholine receptors) are acetylcholine receptors that form G protein-receptor complexes in the cell membranes of certainneurons and other cells. They play several roles, including acting as the main end-receptor stimulated by acetylcholine released from postganglionic fibersin the parasympathetic nervous system. mAChRs are named as such because they are more sensitive to muscarine than to nicotine. Their counterparts are nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), receptor ion channels that are also important in the autonomic nervous system. Many drugs and other substances (for example pilocarpineand scopolamine) manipulate these two distinct receptors by acting as selective agonists or antagonists. Acetylcholine (ACh) is a neurotransmitter found extensively in the brain and the autonomic ganglia. www.MedChemExpress.com 1 mAChR Inhibitors & Modulators (+)-Cevimeline hydrochloride hemihydrate (-)-Cevimeline hydrochloride hemihydrate Cat. No.: HY-76772A Cat. No.: HY-76772B Bioactivity: Cevimeline hydrochloride hemihydrate, a novel muscarinic Bioactivity: Cevimeline hydrochloride hemihydrate, a novel muscarinic receptor agonist, is a candidate therapeutic drug for receptor agonist, is a candidate therapeutic drug for xerostomia in Sjogren's syndrome. IC50 value: Target: mAChR xerostomia in Sjogren's syndrome. IC50 value: Target: mAChR The general pharmacol. properties of this drug on the The general pharmacol. properties of this drug on the gastrointestinal, urinary, and reproductive systems and other… gastrointestinal, urinary, and reproductive systems and other… Purity: >98% Purity: >98% Clinical Data: No Development Reported Clinical Data: No Development Reported Size: 10mM x 1mL in DMSO, Size: 10mM x 1mL in DMSO, 1 mg, 5 mg 1 mg, 5 mg AC260584 Aclidinium Bromide Cat. No.: HY-100336 (LAS 34273; LAS-W 330) Cat. -

77Da2550569e5553dc05b76601

www.ijpsonline.com 2003;13:121-7. RM, Medina-Hernandez MJ. Determination of anticonvulsant drugs in 10. French WN, Matsui FF, Smith SJ. Determination of major impurity pharmaceutical preparations by micellar liquid chromatography. J Liq in chlordiazepoxide formulations and drug substance. J Pharm Sci Chromatogr Related Techno 2004;27:153-70. 2006;64:1545-7. 15. Toral MI, Richter P, Lara N, Jaque P, Soto C, Saavedra M. 11. Stahlmann S, Karl-Artur K. Analysis of impurities by high-performance Simultaneous determination of chlordiazepoxide and clidinium bromide thin-layer chromatography with fourier transform infrared spectroscopy in pharmaceutical formulations by derivative spectrophotometry. Int J and UV absorbance detection in situ measurement: chlordiazepoxide in Pharm 1999;189:67-74. bulk powder and in tablets. J Chromatogr-A 1998;13:145-52. 16. Beckett AH, Stenlake JB. Practice Pharmaceutical Chemistry; 4th ed. 12. Saudagar RB, Saraf S. Spectrophotometric determination of Part II. New Delhi: CBS Publishers; 1997. p. 285. chlordiazepoxide and trifluoperazine hydrochloride from combined dosage form. Indian J Pharm Sci 2007;69:149-52. Accepted 13 August 2009 13. Davidson AG. Assay of chlordiazepoxide and demoxepam in Revised 20 May 2009 chlordiazepoxide formulations by difference spectrophotometry. J Received 24 June 2008 Pharm Sci 1984;73:55-8. 14. Cholbi-Cholbi MF, Martínez-Pla JJ, Sagrado S, Villanueva-Camanas Indian J. Pharm. Sci., 2009, 71 (4): 468-472 Spectrophotometric and Chromatographic Simultaneous Estimation of Amitriptyline Hydrochloride and Chlordiazepoxide in Tablet Dosage Forms SEJAL PATEL* AND N. J. PATEL S. K. Patel College of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Ganpat University, Kherva, Mehsana-382711, Gujarat, India Patel and Patel, et al.: Simultaneous Estimation of Amitriptyline Hydrochloride and Chlordiazepoxide A binary mixture of amitriptyline HCl and chlordiazepoxide was determined by three different methods. -

ST Louis Formulary

Learn About Your Formulary Your drug list, also called a formulary, is the list of drugs covered by St. Louis County Department of Health. Your plan with the St. Louis County Department of Health has specific guidelines you must follow to get prescription drug coverage. You must choose generic medications when they are Many drug companies offer programs to help people available. Generic medications have the same ingredients afford their drugs. We encourage you to ask your doctor as brand drugs, at lower prices. about manufacturer assistance programs. You must fill your prescription at participating pharmacies Drugs are listed on the formulary in alphabetical order by within the St. Louis area: name in the appropriate therapeutic category and class. > CVS > The Medicine Shoppe > Walmart > Schnucks Medications on the High Priority Drug List are covered for > Sam's Club > Beverly Hills Pharmacy ONLY two 30-day fills per year. > Dierbergs > If you are prescribed a High Priority Drug, contact the drug maker to request assistance in getting your medication at reduced or no cost. You must get your prescriptions from Department of > If you do not take this step, you will pay 100% of the Health Physicians discounted drug cost after getting two 30-day fills. > If a medication is prescribed by a non-panel doctor, a > The High Priority Drug List includes: special review is required and can be requested at the • Diabetes drugs: Lantus, Novolog and Novolin number below. • Asthma Inhalers: Atrovent, Spiriva, Ventolin, Proair, Respiclick, Symbicort, Advair, Flovent and Proventil Online Tools Who can I call if I have a question? Our Customer Service Center is available 24 hours a day, 7 Access your pharmacy beneft information through our days a week, 365 days a year to help answer any questions or portal, Members.EnvolveRx.com, and mobile app, concerns you have about your pharmacy benefit. -

THE HARD TRUTH ABOUT PROKINETIC MEDICATION USE in PETS Introduction Pathophysiology/Etiology to That Observed in Dogs

VETTALK Volume 15, Number 04 American College of Veterinary Pharmacists THE HARD TRUTH ABOUT PROKINETIC MEDICATION USE IN PETS Introduction Pathophysiology/Etiology to that observed in dogs. It can be The moving topic of this Vet Talk As with most diseases in the veteri- due to a trichobezoar, dehydration, newsletter will be prokinetic medica- nary world, the etiology and patho- obesity, old age, diabetes, immobility, tions. The availability of information physiology of constipation are varied pain from trauma to the low back, on the many prokinetic agents is var- depending on the species being dis- bladder infection, or an anal sac infec- ied at best so an overall consensus of cussed, where in their gastrointestinal tion. In cases that are more chronic, prokinetic medications will be as- tract the problem is occurring, and underlying disease such as colitis or sessed in this article, hopefully giving any accompanying comorbid condi- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) may better insight to practitioners about tions. be the culprit. On the other hand, the which agents to use in their patients. cause may be idiopathic which is Canines: In man’s best friend, consti- frustrating for both veterinarian and Prevalence pation has many origins. A dog’s patient since this form is most diffi- Chronic constipation and gastroin- digestive tract itself is complex but cult to treat. testinal stasis are highly debilitating ultimately the mass movements and conditions that not only affect human haustral contractions from the large Equines: Despite their large size, patients but our four legged patients intestine (colon), propel feces into the horses have incredibly delicate diges- as well! Though this condition is rectum stimulating the internal anal tive systems. -

The Pharmacology of Prokinetic Agents and Their Role in the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Disorders

The Pharmacology of ProkineticAgents IJGE Issue 4 Vol 1 2003 Review Article The Pharmacology of Prokinetic Agents and Their Role in the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Disorders George Y. Wu, M.D, Ph.D. INTRODUCTION Metoclopramide Normal peristalsis of the gut requires complex, coordinated neural and motor activity. Pharmacologic Category : Gastrointestinal Abnormalities can occur at a number of different Agent. Prokinetic levels, and can be caused by numerous etiologies. This review summarizes current as well as new Symptomatic treatment of diabetic gastric agents that show promise in the treatment of stasis gastrointestinal motility disorders. For these Gastroesophageal reflux e conditions, the most common medications used in s Facilitation of intubation of the small the US are erythromycin, metoclopramide, and U intestine neostigmine (in acute intestinal pseudo- Prevention and/or treatment of nausea and obstruction). A new prokinetic agent, tegaserod, vomiting associated with chemotherapy, has been recently approved, while other serotonin radiation therapy, or post-surgery (1) agonist agents (prucalopride, YM-31636, SK-951, n ML 10302) are currently undergoing clinical o Blocks dopamine receptors in chemoreceptor i t studies. Other prokinetics, such as domperidone, c trigger zone of the CNS (2) A are not yet approved in the US, although are used in f Enhances the response to acetylcholine of o other countries. tissue in the upper GI tract, causing enhanced m s i n motility and accelerated gastric emptying a DELAYED GASTRIC EMPTYING OR h without stimulating gastric, biliary, or c G A S T R O E S O P H A G E A L R E F L U X e pancreatic secretions. -

Title 16. Crimes and Offenses Chapter 13. Controlled Substances Article 1

TITLE 16. CRIMES AND OFFENSES CHAPTER 13. CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS § 16-13-1. Drug related objects (a) As used in this Code section, the term: (1) "Controlled substance" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 2 of this chapter, relating to controlled substances. For the purposes of this Code section, the term "controlled substance" shall include marijuana as defined by paragraph (16) of Code Section 16-13-21. (2) "Dangerous drug" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 3 of this chapter, relating to dangerous drugs. (3) "Drug related object" means any machine, instrument, tool, equipment, contrivance, or device which an average person would reasonably conclude is intended to be used for one or more of the following purposes: (A) To introduce into the human body any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (B) To enhance the effect on the human body of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (C) To conceal any quantity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; or (D) To test the strength, effectiveness, or purity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state. (4) "Knowingly" means having general knowledge that a machine, instrument, tool, item of equipment, contrivance, or device is a drug related object or having reasonable grounds to believe that any such object is or may, to an average person, appear to be a drug related object. -

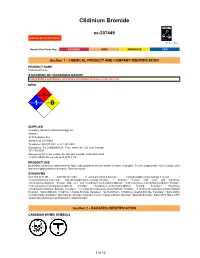

Clidinium Bromide

Clidinium Bromide sc-207449 Material Safety Data Sheet Hazard Alert Code Key: EXTREME HIGH MODERATE LOW Section 1 - CHEMICAL PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION PRODUCT NAME Clidinium Bromide STATEMENT OF HAZARDOUS NATURE CONSIDERED A HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCE ACCORDING TO OSHA 29 CFR 1910.1200. NFPA FLAMMABILITY1 HEALTH1 HAZARD INSTABILITY0 SUPPLIER Company: Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Address: 2145 Delaware Ave Santa Cruz, CA 95060 Telephone: 800.457.3801 or 831.457.3800 Emergency Tel: CHEMWATCH: From within the US and Canada: 877-715-9305 Emergency Tel: From outside the US and Canada: +800 2436 2255 (1-800-CHEMCALL) or call +613 9573 3112 PRODUCT USE Quaternary ammonium antimuscarinic agent with peripheral actions similar to those of atropine. For the symptomatic relief of peptic ulcer and other gastrointestinal disorders. Taken by mouth. SYNONYMS C22-H26-Br-N-O3, C22-H26-Br-N-O3, "1-azoniabicyclo(2.2.2)octane, 3-[(hydroxydiphenylacetyl)oxy]-1-methyl-, ", "1-azoniabicyclo(2.2.2)octane, 3-[(hydroxydiphenylacetyl)oxy]-1-methyl-, ", bromide, "benzilic acid, ester with 3-hydroxy- 1-methylquinuclidinium", "benzilic acid, ester with 3-hydroxy-1-methylquinuclidinium", "3-(benziloyloxy)-1-methylquinuclidinium bromide", "3-(benziloyloxy)-1-methylquinuclidinium bromide", "3-hydroxy-1-methylquinuclidinium bromide benzilate", "3-hydroxy- 1-methylquinuclidinium bromide benzilate", "1-methyl-3-benziloxyloxy-quinuclidinium bromide", "1-methyl-3-benziloxyloxy-quinuclidinium bromide", "quinuclidinium, 3-hydroxy-1-methyl-bromide, benzilate", "quinuclidinium, 3-hydroxy-1-methyl-bromide, benzilate", "quinuclidinol methylbromide, benzilate", Apo-Chlorax, Chlorax, Clipoxide, Corium, Librax, Libraxin, Quarzan, "Quarzan bromide", RO-2-3773, RO-2-3773, "quaternary ammonium antimuscarinic/ anticholinergic" Section 2 - HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION CANADIAN WHMIS SYMBOLS 1 of 13 Clidinium Bromide sc-207449 Material Safety Data Sheet Hazard Alert Code Key: EXTREME HIGH MODERATE LOW EMERGENCY OVERVIEW RISK Harmful if swallowed. -

Dizziness/Balance Evaluation Patient Instructions You Are Scheduled for a Test of Your Balance System

Dizziness/Balance Evaluation Patient Instructions You are scheduled for a test of your balance system. There are a few things you should know prior to your appointment. MEDICATIONS Certain medications affect the test results. Below is a partial list of medications that should not be taken for 48 hours prior to the test. Ask your doctor if you have concerns about discontinuing your medications. The list below is a partial list with generic name first and trademark name bolded in parenthesis. • Alcohol - beer, wine, liquor, cough medicine • Medications commonly used to reduce dizziness and nausea - Meclizine (Antivert, Bonnine, Ru-Vert-M), Hydroxyzine (Atarax, Vistaril), Lorazepam (Ativan), Diphenhydramine (Benadryl), Prochlorperazine (Compazine), Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine), Clonazepam (Klonipin), Cyclizine (Marezine), Promethazine (Phenergan), Trimethobenzamine (Tigan), Diazepam (Valium), Nearly all motion sickness patches or medications. OTHER MEDICATIONS • Analgesics/Narcotics - Codeine, Demerol, Phenaphen, Tylenol with Codeine, Percocet, Darvocet • Anti-histamines - Fexofenadine (Allegra), Loratadine (Claritin, Alavert), Chlorpheniramine (Chlor-Trimeton, Efidac, Teldrin), Brompheniramine (Dimetane), Clemastine (Tavist), Cetirizine (Zyrtec), nearly all-over-the-counter allergy or flu/cold medicines • Sedatives - Flurazepam (Dalmane), Triazolam (Halcion), Pentobarbital (Nembutal), Temazepam (Restoril), Secobarbital (Seconal), among others. • Tranquilizers/Anti-anxiety medications - Chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride and clidinium bromide (Librax),