Network Television and the Digital Threat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Are You What You Watch?

Are You What You Watch? Tracking the Political Divide Through TV Preferences By Johanna Blakley, PhD; Erica Watson-Currie, PhD; Hee-Sung Shin, PhD; Laurie Trotta Valenti, PhD; Camille Saucier, MA; and Heidi Boisvert, PhD About The Norman Lear Center is a nonpartisan research and public policy center that studies the social, political, economic and cultural impact of entertainment on the world. The Lear Center translates its findings into action through testimony, journalism, strategic research and innovative public outreach campaigns. Through scholarship and research; through its conferences, public events and publications; and in its attempts to illuminate and repair the world, the Lear Center works to be at the forefront of discussion and practice in the field. futurePerfect Lab is a creative services agency and think tank exclusively for non-profits, cultural and educational institutions. We harness the power of pop culture for social good. We work in creative partnership with non-profits to engineer their social messages for mass appeal. Using integrated media strategies informed by neuroscience, we design playful experiences and participatory tools that provoke audiences and amplify our clients’ vision for a better future. At the Lear Center’s Media Impact Project, we study the impact of news and entertainment on viewers. Our goal is to prove that media matters, and to improve the quality of media to serve the public good. We partner with media makers and funders to create and conduct program evaluation, develop and test research hypotheses, and publish and promote thought leadership on the role of media in social change. Are You What You Watch? is made possible in part by support from the Pop Culture Collaborative, a philanthropic resource that uses grantmaking, convening, narrative strategy, and research to transform the narrative landscape around people of color, immigrants, refugees, Muslims and Native people – especially those who are women, queer, transgender and/or disabled. -

UMG V Veoh 9Th Opening Brief.Pdf

Case: 09-56777 04/20/2010 Page: 1 of 100 ID: 7308924 DktEntry: 11-1 No. 09-56777 ____________ IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT ___________________ UMG RECORDINGS, INC.; UNIVERSAL MUSIC CORP.; SONGS OF UNIVERSAL, INC.; UNIVERSAL-POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING, INC.; RONDOR MUSIC INTERNATIONAL, INC.; UNIVERSAL MUSIC—MGB NA LLC; UNIVERSAL MUSIC—Z TUNES LLC; UNIVERSAL MUSIC—MBG MUSIC PUBLISHING LTD., Plaintiffs-Appellants v. VEOH NETWORKS, INC., Defendant-Appellee. _______________________________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California, Western Division—Los Angeles Honorable A. Howard Matz, District Judge __________________________________ APPELLANTS’ BRIEF _____________________________________ Steven Marenberg, Esq. State Bar No. 101033 Brian Ledahl, Esq. State Bar No. 186579 Carter Batsell State Bar No. 254396 IRELL & MANELLA, LLP 1800 Avenue of the Stars Suite 900 Los Angeles, California 90067 Telephone: (310) 277-1010 Facsimile: (310) 203-7199 ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANTS 2221905 Case: 09-56777 04/20/2010 Page: 2 of 100 ID: 7308924 DktEntry: 11-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT................................................ 2 JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT ................................................................. 3 ISSUES PRESENTED ..................................................................................... 4 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........................................................................ 6 FACTS ........................................................................................................... -

NCA All-Star National Championship Wall of Fame

WALL OF FAME DIVISION YEAR TEAM CITY, STATE L1 Tiny 2019 Cheer Force Arkansas Tiny Talons Conway, AR 2018 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2017 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2016 The Stingray All Stars Grape Marietta, GA 2015 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2014 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2013 The Stingray All Stars Marietta, GA 2012 Texas Lonestar Cheer Company Houston, TX 2011 The Stingray All Stars Marietta, GA 2010 Texas Lonestar Cheer Company Houston, TX 2009 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Dallas, TX 2008 Woodlands Elite The Woodlands, TX 2007 The Pride Addison, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1.1 Tiny Prep D2 2019 East Texas Twisters Ice Ice Baby Canton, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1.1 Tiny Prep 2019 All-Star Revolution Bullets Webster, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1 Tiny Prep 2018 Liberty Cheer Starlettes Midlothian, TX 2017 Louisiana Rebel All Stars Faith (A) Shreveport, LA Cheer It Up All-Stars Pearls (B) Tahlequah, OK 2016 Texas Legacy Cheer Laredo, TX 2015 Texas Legacy Cheer Laredo, TX 2014 Raider Xtreme Raider Tots Lubbock, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1 Mini 2008 The Stingray All Stars Marietta, GA 2007 Odyssey Cheer and Athletics Arlington, TX 2006 Infinity Sports Kemah, -

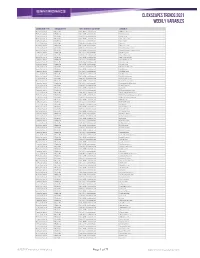

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Annual Report 2008

® Annual Report 2008 • Revised corporate mission: To provide convenient access to 2007 media entertainment • Announced decisive steps to strengthen the core rental business, enhance the company’s retail offering, and embrace digital content delivery • Positioned BLOCKBUSTER Total Access™ into a profi table and stable business • Completed Blu-ray Disc™ kiosk installation • Launched a new and improved blockbuster.com and integrated 2008 Movielink’s 10,000+ titles into the site • Improved studio relationships, with 80% of movie studios currently committed to revenue share arrangements • Enhanced approximately 600 domestic stores • Improved in-stock availability to 60% during the fi rst week a hot new release is available on DVD • Expanded entertainment related merchandise, including licensed memorabilia • Launched “Rock the Block” Concept in Reno, Dallas and New York City • Introduced consumer electronics, games and game merchandise in approximately 4,000 domestic stores • Launched new products and services nationally, including event ticketing through alliance with Live Nation • Continued to improve product assortment among confection and snack items • Launched BLOCKBUSTER® OnDemand through alliance with 2Wire® • Announced alliance with NCR Corporation to provide DVD vending 2009 • Teamed with Sonic Solutions® to provide consumers instant access to Blockbuster’s digital movie service across extensive range of home and portable devices • Began to gradually roll-out “Choose Your Terms” nationally • Announced pilot program to include online -

Move Over, Amateurs

Web Video: Move Over, Amateurs As more professionally produced content finds a home online, user- generated video becomes less alluring to viewers—and advertisers by Catherine Holahan November 20, 2007 Amateur filmmakers hoping to win fame for amusing moments captured on camcorder ought to stick to TV's long-running America's Funniest Home Videos. These days they're not getting much love on the Web. One after another, online video sites that have long showcased such fare as skateboarding dogs and beer-drenched parties are scaling back their focus on user- generated clips, often in favor of professionally produced programming. "People would rather watch content that has production value than watch their neighbors in the garage," says Matt Sanchez, co-founder and chief executive of VideoEgg, a company that provides Web video tools, ads, and advertising features for online video providers and Web application developers. On Nov. 13 social networking site Bebo said it would open its pages to top media companies in hopes of luring and engaging viewers. "As more and more interesting content from major media brands becomes available, [online viewers] are going to share that more and more because those are the brands they identify with," says Bebo President Joanna Shields. Another site, ManiaTV, recently canceled its user-generated channels altogether (BusinessWeek.com, 10/22/07). The 3,000 user-generated channels simply didn't pull in enough viewers, ManiaTV CEO Peter Hoskins says. Roughly 80% of people were watching the professional content produced by celebrities such as musician Dave Navarro and comedian Tom Green. "What we found out is, we don't need the classical user-generated talent when we have the Hollywood talent that wants to Coverage secured by Kel & Partners www.kelandpartners.com work with us," Hoskins says. -

Using Artistic Markers and Speaker Identification for Narrative-Theme

Using Artistic Markers and Speaker Identification for Narrative-Theme Navigation of Seinfeld Episodes Gerald Friedland, Luke Gottlieb, and Adam Janin International Computer Science Institute 1947 Center Street, Suite 600 Berkeley, CA 94704-1198 [fractor|luke|janin]@icsi.berkeley.edu Abstract ysis, thus completely ignoring the rich information within the video/audio medium. Even portable devices such as This article describes a system to navigate Seinfeld smartphones are sufficiently powerful for more intelligent episodes based on acoustic event detection and speaker browsing than play/pause/rewind. identification of the audio track and subsequent inference of In the following article, we present a system that ex- narrative themes based on genre-specific production rules. tends typical navigation features significantly. Based on the The system distinguishes laughter, music, and other noise idea that TV shows are already conceptually segmented by as well as speech segments. Speech segments are then iden- their producers into narrative themes (such as scenes and tified against pre-trained speaker models. Given this seg- dialog segments), we present a system that analyzes these mentation and the artistic production rules that underlie “markers” to present an advanced “narrative-theme” navi- the “situation comedy” genre and Seinfeld in particular, gation interface. We chose to stick to a particular exam- the system enables a user to browse an episode by scene, ple presented in the description of the ACM Multimedia punchline, and dialog segments. The themes can be filtered Grand Challenge [1] ; namely, the segmentation of Seinfeld by the main actors, e.g. the user can choose to see only episodes 2. -

Investigating the Network Characteristics of Two Popular Web-Based Video Streaming Sites

European Scientific Journal November 2017 edition Vol.13, No.33 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Investigating the Network Characteristics of Two Popular Web-Based Video Streaming Sites Dr. Feras Mohammed Almatarneh University of Tabuk Department of Computer Science, College Duba Saudi Arabia Doi: 10.19044/esj.2017.v13n33p305 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2017.v13n33p305 Abstract The determinants of the strategies to be employed by video streaming sites are application (mobile devices or web browsers) and container of the video application. They affect video streaming network characteristics, which is often the traffic flow, and its quality. It is against this background that studies on streaming strategies suggested the need to investigate and identify the relationship between buffer time, video stream protocol, packet speed and size, upload time, and waiting period, specifically to aid network administrative support in case of network traffic bottlenecks. In view of this, this study investigates the network characteristics of YouTube and Vimeo, using experimental methodology, and involving WireShark as network analyzer. Google Chrome and Firefox are the web browsers employed, while packet size, protocols, packet interval, TCP window size and accumulation ratio are the metrics. Short ON-OFF, Long ON-OFF, and No ON-OFF cycles are the three streaming strategies identified. It is further shown that both Vimeo and YouTube employ these strategies but the choice depends on the container of the video streamed. Keywords: Network characteristics, streaming strategies, video streaming sites, traffic flow Introduction Video streaming is one of the techniques for video distribution over the internet. It helps in lecture and news broadcast, and allows users’ access, without any geographical constraints (Karki, Seenivasan, Claypool, & Kinicki, 2010; Tan & Zakhor, 1999). -

Shon Hedges Editor

SHON HEDGES EDITOR FEATURES iGILBERT Paloma Pictures Prod: Cynthia Hargrave, Adrian Martinez Dir: Adrian Martinez Anthony Vorhies PICTURE PARIS (Short) For Goodness Sake Prod: Brad Hall, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Julie Snyder Dir: Brad Hall *Official Selection, Tribeca Film Festival, 2012 GENEROSITY OF EYE (Documentary) For Goodness Sake Prod: Brad Hall, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Julie Snyder Dir: Brad Hall ABOUT SUNNY (Associate Editor) On the Line Prods./ Prod: Lauren Ambrose, Blythe Robertson, Mike Ryan Dir: Bryan Wizemann Votiv Films AFRICAN ADVENTURE: nWave Pictures Prod: Ben Stassen Dir: Ben Stassen SAFARI IN THE OKAVANGO (Documentary) TELEVISION NEW AMSTERDAM (Season 1) Universal/NBC Prod: Peter Horton, David Schulner Dir: Various THE ORVILLE (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/Fox Prod: Seth McFarlane, David Goodman Dir: Various Brannon Braga, John Cassar BULL (Season 1) CBS Studios/CBS Prod: Mark Goffman, Paul Attanasio Dir: Various BLACK SAILS (Ep. 106, 209, 302) Starz Prod: Michael Bay, Jonathan Steinberg, Dan Shotz Dir: T.J. Scott, Lukas Ettlin HEROES REBORN (Season 1) Universal/NBC Prod: Tim Kring, Lori Motyer Dir: Various HOMELAND (Season 2) Fox 21/Showtime Prod: Alex Gansa, Meredith Stiehm, Howard Gordon Dir: Various (Additional Editing) THE KILLING (Season 2) Fox TV/AMC/Netflix Prod: Veena Sud, Mikkel Bondesen, Ron French Dir: Various (Assistant Editor) SMASH (Pilot) (Assistant Editor) Universal/NBC Prod: Justin Falvey, Darryl Frank, Marc Shaiman Dir: Michael Mayer IN PLAIN SIGHT (Ep. 403) USA Prod: David Maples Dir: Michael Schultz (Assistant Editor) IN TREATMENT (Ep. 326, 327, 328) HBO Prod: Paris Barclay, Anya Epstein Dir: Various (Assistant Editor) RUBICON (Season 1) Warner Horizon/AMC Prod: Henry Bromwell, Jason Horwitch Dir: Various (Assistant Editor) A MARRIAGE (Pilot) CBS Prod: Ed Zwick, Marshall Herzkovitz Dir: Marshall Herskovitz QUARTERLIFE (3 episodes) NBC Prod: Ed Zwick, Marshall Herzkovitz Dir: Marshall Herskovitz, Catherine Jelski 405 S Beverly Drive, Beverly Hills, California 90212 - T 310.888.4200 - F 310.888.4242 www.apa-agency.com . -

Dhspring2014 DH Program

Oren Katzeff, Head of Programming, Tastemade Digital Hollywood Spring David Karp, EVP, Business Development, SnagFilms, Inc. The Digital Future has Arrived! Jason Berger, founder & Executive Producer, Kids at Play 1 May 5th - 8th, 2014 Elizabeth Brooks, Head of Marketing, Live Nation Labs The Ritz Carlton Hotel, Marina del Rey, California Sang H. Cho, President and CEO, Mnet Ann Greenberg, Founder & Chief Tinkerer, Sceneplay, The Strategic Sessions - Let's Get Started! Moderator Monday, May 5th Track II: Poolside Tent I (FINANCE) 10:00 AM - 11:15 AM Valuing and Financing Entertainment Content: Track I:Ballroom Terrace (BrandPower) (ADVERT) Movies, Television and Online Video, From VC Native Advertising: Digital Advertising & Equity to Crowdfunding Industry Gets Serious About Better Advertising Join a group of influential players in the media, entertainment Matt Palmer, SVP and GM, Demand Media and tech finance worlds for an enlightening look at emerging Andrew Budkofsky, EVP, Sales and Partnerships, Digital growth areas in our industry. They reveal where the value and Trends opportunities are, who's investing and whether we're headed for Greg Portell, Partner, A.T. Kearney a bubble or sustained hypergrowth in the convergence space. Mike Kisseberth, Chief Revenue Officer, TechMedia Network Mike LaSalle, Partner, Shamrock Capital Advisors Roger Camp, Partner & Chief Creative Officer, CAMP + KING Marti Frucci, Managing Director, Digital Capital Advisors Aron Levitz, SVP, Wattpad René Bourdages, CEO, Elevado Media, Inc. Shawn Gold, Advisor -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn. -

TSC Resume-Current for Website-Sheet1

FEATURE FILMS (CONDENSED LIST): OFFICE CHRISTMAS PAETY DreamWorks Pictures GUARDIANS of the GALAXY Vol. 2 Marvel Studios SULLY Warner Bros. GIFTED Fox Searchlight Pictures MIRACLES FROM HEAVEN SONY Pictures Entertainment CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR Marvel Studios IN DUBIOUS BATTLE Rabbit Bandini Productions THE 5th WAVE SONY Pictures Entertainment THE NICE GUYS Warner Bros. VACATION New Line Cinema TAKEN 3 20th Century Fox GET ON UP Universal Pictures BARELY LETHAL RKO Pictures BLENDED Universal Pictures ENDLESS LOVE Universal Pictures THE HOMESMAN Briggs & Cuddy Inc. NEED FOR SPEED DreamWorks Pictures PRISONERS Alcon Entertainment THE LAST OF ROBIN HOOD Killer Films IDENTITY THIEF Universal Pictures * THE DARK KNIGHT RISES Warner Bros * A BETTER LIFE Summit Entertainment !1 * I LOVE YOU, MAN DreamWorks * GOOD NIGHT AND GOOD LUCK Warner Independent Pictures * DREAMGIRLS DreamWorks Pictures * EVAN ALMIGHTY Universal Pictures * 17 AGAIN New Line Cinema * G-FORCE Walt Disney Pictures * RAY Universal Pictures * ROLE MODELS Universal Pictures * SUPERHERO MOVIE MGM * I COULD NEVER BE YOUR WOMAN Scott Rudin Productions * THE HEARTBREAK KID DreamWorks Pictures * SMOKIN' ACES Universal Pictures * FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION Warner Bros. * SCHOOL FOR SCOUNDRELS MGM * FUN WITH DICK AND JANE Columbia Pictures * MEET THE FOCKERS Universal Pictures * BRUCE ALMIGHTY Universal Pictures * KICKING AND SCREAMING Universal Pictures * ART SCHOOL CONFIDENTIAL SONY Pictures Classics * BE COOL MGM * ALONG CAME POLLY Universal Pictures * DRAGONFLY Universal Pictures * CHRISTMAS WITH THE KRANKS Columbia Pictures * Co-OWNER and Casting Director - SMITH & WEBSTER-DAVIS CASTING - 2/1999 thru 2/2012 !2 * FAT ALBERT 20TH Century Fox * BIKER BOYZ DreamWorks Pictures * BRINGING DOWN THE HOUSE Disney (Touchstone) * SURVIVING CHRISTMAS DreamWorks Pictures * SIDEWAYS Fox Searchlight Pictures * COYOTE UGLY Disney(Touchstone) * THIRTEEN DAYS New Line Cinema * THE WHOLE 10 YARDS Warner Bros.