Rev4 a Tree a Boy and a Fish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed King Arthur’s quest for it in the Middle Ages became a large part of his legend. Monty Python and Indiana Jones launched their searches in popular 1974 and 1989 movies. The mythic quest for the Holy Grail, the name given in Western tradition to the chal- ice used by Jesus Christ at his Passover meal the night before his death, is now often a metaphor for a quintessential search. In the illustrious history of baseball, the “holy grail” is a ranking of each player’s overall value on the baseball diamond. Because player skills are multifaceted, it is not clear that such a ranking is possible. In comparing two players, you see that one hits home runs much better, whereas the other gets on base more often, is faster on the base paths, and is a better fielder. So which player should rank higher? In Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, I identified which players were best at getting a hit in a given at-bat, calling them the best hitters. Many reviewers either disapproved of or failed to note my definition of “best hitter.” Although frequently used in base- ball writings, the terms “good hitter” or best hitter are rarely defined. In a July 1997 Sports Illustrated article, Tom Verducci called Tony Gwynn “the best hitter since Ted Williams” while considering only batting average. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

Al Brancato This Article Was Written by David E

Al Brancato This article was written by David E. Skelton The fractured skull Philadelphia Athletics shortstop Skeeter Newsome suffered on April 9, 1938 left a gaping hole in the club’s defense. Ten players, including Newsome after he recovered, attempted to fill the void through the 1939 season. One was Al Brancato, a 20- year-old September call-up from Class-A ball who had never played shortstop professionally. Enticed by the youngster’s cannon right arm, Athletics manager Connie Mack moved him from third base to short in 1940. On June 21, after watching Brancato retire Chicago White Sox great Luke Appling on a hard-hit grounder, Mack exclaimed, “There’s no telling how good that boy is going to be.”1 Though no one in the organization expected the diminutive (5-feet-nine and 188 pounds) Philadelphia native’s offense to cause fans to forget former Athletics infield greats Home Run Baker or Eddie Collins, the club was satisfied that Brancato could fill in defensively. “You keep on fielding the way you are and I’ll do the worrying about your hitting,” Mack told Brancato in May 1941.2 Ironically, the youngster’s defensive skills would fail him before the season ended. In September, as the club spiraled to its eighth straight losing season, “baseball’s grand old gentleman” lashed out. “The infielders—[Benny] McCoy, Brancato and [Pete] Suder—are terrible,” Mack grumbled. “They have hit bottom. Suder is so slow it is painful to watch him; Brancato is erratic and McCoy is—oh, he’s just McCoy, that’s all.” 3 After the season ended Brancato enlisted in the US Navy following the country’s entry into the Second World War. -

BASE BOWMAN ICONS PROSPECTS 1 Wander Franco

BASE BOWMAN ICONS PROSPECTS 1 Wander Franco Tampa Bay Rays™ 4 Cristian Pache Atlanta Braves™ 5 Matt Manning Detroit Tigers® 7 Casey Mize Detroit Tigers® 9 Dylan Carlson St. Louis Cardinals® 10 Sixto Sanchez Miami Marlins® 11 JJ Bleday Miami Marlins® 13 Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® 14 Jasson Dominguez New York Yankees® 17 Nick Madrigal Chicago White Sox® 18 Royce Lewis Minnesota Twins® 19 Jo Adell Angels® 22 MacKenzie Gore San Diego Padres™ 26 Julio Rodriguez Seattle Mariners™ 27 Adley Rutschman Baltimore Orioles® 28 Nate Pearson Toronto Blue Jays® 30 CJ Abrams San Diego Padres™ 32 Nolan Gorman St. Louis Cardinals® 34 Jarred Kelenic Seattle Mariners™ 37 Forrest Whitley Houston Astros® 38 Marco Luciano San Francisco Giants® 39 Bobby Witt Jr. Kansas City Royals® 44 Andrew Vaughn Chicago White Sox® 46 Joey Bart San Francisco Giants® 50 Riley Greene Detroit Tigers® BOWMAN ICONS ROOKIES 2 Luis Robert Chicago White Sox® Rookie 3 Justin Dunn Seattle Mariners™ Rookie 6 Bobby Bradley Cleveland Indians® Rookie 8 Yoshi Tsutsugo Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie 12 Aaron Civale Cleveland Indians® Rookie 15 Trent Grisham San Diego Padres™ Rookie 16 Dustin May Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 20 A.J. Puk Oakland Athletics™ Rookie 21 Nico Hoerner Chicago Cubs® Rookie 23 Sean Murphy Oakland Athletics™ Rookie 24 Yordan Alvarez Houston Astros® Rookie 25 Jordan Yamamoto Miami Marlins® Rookie 29 Michel Baez San Diego Padres™ Rookie 31 Shun Yamaguchi Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 33 Anthony Kay Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 35 Brusdar Graterol Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 36 Bo -

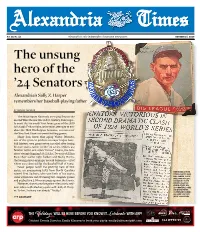

OCTOBER 24, 2019 the Unsung Hero of the ’24 Senators Alexandria’S Sally Z

Alexandria Times Vol. 15, No. 43 Alexandria’s only independent hometown newspaper. OCTOBER 24, 2019 The unsung hero of the ’24 Senators Alexandria’s Sally Z. Harper remembers her baseball-playing father BY DENISE DUNBAR The Washington Nationals are vying for just the second World Series title in D.C. history. Fans eager- ly await the Nationals’ first home game of the 2019 fall classic Friday night as the team attempts to em- ulate the 1924 Washington Senators, winners over the New York Giants in seven thrilling games. Many fans know that aging Walter Johnson, one of the greatest pitchers in major league base- ball history, won game seven in relief after losing his two starts earlier in the ‘24 series. Others are familiar with Leon Allen “Goose” Goslin, the Sen- ators’ young slugging left fielder; 34-year-old Sam Rice, their stellar right fielder; and Bucky Harris, the young player-manager second baseman – all of whom were destined for the Baseball Hall of Fame. Fewer people recall the pitching hero of that series, an unassuming lefty from North Carolina MEMORABILIA FROM named Tom Zachary, who won both of his starts, TOM ZACHARY'S BASE- came within one out of tossing two complete games BALL CAREER, CLOCK- WISE FROM TOP LEFT: and pitched to a 2.04 run average against the Giants. HIS WATCH FOB FOR However, there’s one longtime Alexandria resi- WINNING THE 1924 WORLD SERIES, HIS dent who recalls Zachary quite well: Sally Z. Harp- 1933 BASEBALL CARD er. To her, Zachary was simply “Daddy.” AND A NEWSPAPER CLIPPING DESCRIBING HIS GAME 2 VICTORY SEE ZACHARY | 6 IN THE 1924 SERIES. -

Kit Young's Sale #132

Page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #132 2017 TOPPS NATIONAL RETRO SETS Just In!! Exciting news: For the 10th time since 2005 we have the popular Topps Retro sets. As in previous years, Topps has produced special issue cards of Hall of Famers, all in the style of the popular 1987 set - this year’s set features 5 all time greats - Ted Williams, Cal Ripken Jr., Johnny Bench, Nolan Ryan and Ken Griffey Jr. These are regular sized cards that were issued only to VIP attendees at the 2017 National Convention, making them pretty scarce. Backs show that cards were spe- cially issued at The National. We suggest you order soon - supply this year is limited. All cards Mint in the original sealed packs. Only $29.95 (2 set special $49.95) 1951 TOPPS RED BACKS & BLUE BACKS 1951 RED BACKS Yogi Berra Yakees NR-MT Warren Spahn Braves 1951 BLUE BACKS 125.00; EX-MT 95.00; EX #30..............PSA 6 EX-MT Richie Ashburn Phillies 62.00; VG-EX 50.00; GD- $79.95 NR-MT 255.00 VG-EX $35.00 GD-VG Johnny Groth Tigers.....NR-MT VG 31.00 49.00; EX-MT 42.00 Sid Gordon Braves....EX-MT $18.00 Sam Jethroe Braves......PSA 8 NM/ 13.00; EX 7.50; VG 5.50 Gil Hodges Dodgers......... MT 59.95; VG-EX 21.00 Ferris Fain A’s...........NR-MT NR-MT 69.00; EX 35.00; Mickey Vernon Senators....NR-MT 17.00; VG-EX 13.00 VG 23.00; GD-VG 16.00 49.00 Vern Stephens RedSox.EX- Hank Thompson Giants... -

2012 National Treasures Baseball Player Hit Totals

2012 National Treasures Baseball Player Hit Totals Non- Rookies Player Auto Relic Only Total Adam Dunn 99 99 Adam Jones 218 218 Adrian Beltre 104 124 228 Adrian Gonzalez 144 144 Al Kaline 80 199 279 Al Simmons 6 445 451 Albert Pujols 603 603 Alex Avila 87 87 Alex Rodriguez 397 397 Alfonso Soriano 139 139 Amelia Earhart 5 5 Andre Dawson 65 134 199 Andrew McCutchen 89 136 225 Arky Vaughan 75 75 Aroldis Chapman 138 138 Austin Jackson 138 138 Barry Larkin 81 63 144 Bernie Williams 34 34 Bert Blyleven 95 80 175 Bill Dickey 20 126 146 Bill Madlock 25 25 Bill Mazeroski 60 60 Bill Terry 20 397 417 Billy Herman 20 239 259 Billy Martin 3 109 112 Billy Southworth 2 15 17 Billy Williams 90 42 132 Bo Jackson 42 42 Bob Feller 85 381 466 Bob Gibson 45 4 49 Bobby Doerr 85 45 130 Bobby Thomson 99 99 Brett Gardner 86 86 Brooks Robinson 85 110 195 Burleigh Grimes 20 117 137 Buster Posey 109 199 308 Cal Ripken Jr. 82 247 329 Carl Crawford 24 24 Carl Furillo 15 273 288 Carl Yastrzemski 73 126 199 2012 National Treasures Baseball Total Hits by Player www.groupbreakchecklists.com Carlos Beltran 99 99 Carlos Gonzalez 139 139 Carlton Fisk 81 134 215 Catfish Hunter 20 128 148 CC Sabathia 38 38 Charlie Gehringer 20 308 328 Chipper Jones 95 129 224 Chuck Klein 2 470 472 Clayton Kershaw 43 124 167 Cliff Lee 50 50 Curtis Granderson 360 360 Dale Murphy 143 129 272 Dave Bancroft 10 210 220 Dave Parker 76 76 David Freese 39 39 David Justice 42 42 David Ortiz 68 68 David Wright 110 1 111 Deion Sanders 35 1 36 Dennis Eckersley 75 132 207 Derek Jeter 552 552 Dizzy Dean -

1962 Minnesota Twins Media Guide

MINNESOTA TWINS METROPOLITAN STADIUM - BLOOMINGTON, MINNESOTA /eepreieniin the AMERICAN LEAGUE __flfl I/ic Upper l?ic/we1 The Name... The name of this baseball club is Minnesota Twins. It is unique, as the only major league baseball team named after a state instead of a city. The reason unlike all other teams, this one represents more than one city. It, in fact, represents a state and a region, Minnesota and the Upper Midwest, in the American League. A survey last year drama- tized the vastness of the Minnesota Twins market with the revelation that up to 47 per cent of the fans at weekend games came from beyond the metropolitan area surrounding the stadium. The nickname, Twins, is in honor of the two largest cities in the Upper Midwest, the Twin Cities of Minne- apolis and St. Paul. The Place... The home stadium of the Twins is Metropolitan Stadium, located in Bloomington, the fourth largest city in the state of Minnesota. Bloomington's popu- lation is in excess of 50,000. Bloomington is in Hen- nepin County and the stadium is approximately 10 miles from the hearts of Minneapolis (Hennepin County) and St. Paul (Ramsey County). Bloomington has no common boundary with either of the Twin Cities. Club Records Because of the transfer of the old Washington Senators to Minnesota in October, 1960, and the creation of a completely new franchise in the Na- tion's Capital, there has been some confusion over the listing of All-Time Club records. In this booklet, All-Time Club records include those of the Wash- ington American League Baseball Club from 1901 through 1960, and those of the 1961 Minnesota Twins, a continuation of the Washington American League Baseball Club. -

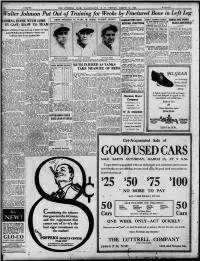

Walter Johnson Put out Oftraining for Weeks Byfractured Bone In

38 SPORTS. THE EVENING STAR, -WASHINGTON. D. C., FRIDAY, MARCH 11, 1927. SPORTS. Walter Johnson Put Out of Training for Weeks by Fractured Bone in Left Leg CUNTS | GRIFF PITCHERS IN START OF SERIES AGAINST | SANDLOTTERS BUSY HOOKY THOMAS FARMED COMBS AND YANKS . COMING HOME WITH LIMB I II TO ROCHESTER CLUB " THE * ! % ‘ * * * ‘•'< •'• • t: 1 v .1 /•V- v MEETING, PRACTICING The business of pruning the REACH AGREEMENT IN CAST; BLOW TO TEAM h* Washington roster from 40 to 35 started with the r / W \ meetings players was today By Ihf AiMditml Ptmi. ¦ Many ball are sched- base uled for the balance of the week and announcement from Tampa, Fla., RICHMOND, Ky.. March 11.—Earl week, practice sessions (irifHth next while by President Clark that Combs, center fielder of the Now York (Absence of Barney From Line-up at Outset of Cam- will be held Sunday by several dia- ' Clarence (Hooky) Thomas has been League Bane Club, has mond outfits. American Ball and sent to the Rochester club of the accepted the nalary condition* offered paign WillHandicap Griffmen— —Burke Ballston A. C- of Arlington County International league on option. In a telegram received from Col. Jacob and Hartfords will hold practice over Thomas is the big lefthand pitch- Ruppert and will sign a contract Im- Form Against Phils. the week end. er, who was inspected at camp last mediately. he said. Coffman Show Spring and subsequently farmed to Combs plans to leave Saturday or Harvard Juniors will meet tomor- Birmingham, whk-h, in turn, placed Monday to join the'Yankee* at their row night at 307 S street northeast him with Rochester. -

1961 Minnesota Twins Media Guide

MINNESOTA TWINS BASEBALL CLUB METROPOLITAN STADIUM HOME OF MINNESOTA TWINS /EprP.1n/inf/ /I , AMERICAN LEAGUE _j1,, i'; , Upp er /'ZIweoi Year of the Great Confluence For the big-league starved fans of the Upper Midwest, the Big Day came on October 26, 1 9 d6a0t,e of the transfer of the American League Senators from Washington to the Minneapolis and St. Paul territory, and the merger of three proud baseball traditions. For their new fans to gloat about, the renamed Minnesota Twins brought with them three pennants won in Washington, in 1924, '25 and '33, and a world championship in 1924. Now, their new boosters could claim a share of such Senator greats as Clark C. (Old Fox) Griffith, Wolter (Big Train) Johnson, Joe Cronin, Lean (Goose) Goslin, Clyde (Deerfoot) Milan, Ed Delahanty, James (Mickey) Vernon, Roy Sievers, and others. Reciprocally, the Twins could now absorb the glories of 18 American Asso- ciation pennants - nine won by St. Paul and nine by Minneapolis - in 59 seasons. They could be reminded of the tremendous pennant burst by St. Paul in 1920, with the Saints winning 115, losing only 49, posting a .701 percentage, and running away from Joe McCarthy's second-place Louisville Colonels by 28 1/2 games. Mike Kelley, the American Association's grand old man, managed that one and four other Saints flag winners before buying the Minneapolis club and putting together three more championship combinations. The pattern for winning boll in St. Paul was set early, in the first year of minor league ball, in fact. -

LEFTIES, the FAMOUS and the INFAMOUS

LEFTIES, the FAMOUS and the INFAMOUS U.S. PRESIDENTS RECORDING ARTISTS James Garfield, 20th President Kurt Cobain (Nirvana) Herbert Hoover, 31st President Phil Collins (Genesis) Harry S. Truman, 33rd President Don and Phil Everly (The Everly Gerald Ford, 38th President Brothers - 100% of the group!) George H.W. Bush, 41st President Jimi Hendrix Bill Clinton, 42nd President Paul McCartney (the Beatles; Wings) Barack Obama, 44th President Paul Simon (Simon & Garfunkel) Tiny Tim Some notes about the Presidents: Rudy Valee (1) Ronald Reagan was rumored to have VISUAL ARTISTS been born left-handed but was forced to switch early in his life. However, no Don Adams (Actor) documentation, photos, or witnesses Dan Aykroyd (Actor) have come forth to verify. So he is Eddie Albert (Actor) disqualified from this elite list. Tim Allen (Actor) June Allyson (2) Grover Cleveland was elected to Harry Anderson (Actor) two non-consecutive terms and is Amitabh Bachchan (Indian actor) counted twice. Herschel Bernardi Robert Blake (Actor) (3) The totals, then, is out of 43 US Matthew Broderick (Actor) Presidents, 7 have been left-handed. Bruce Boxleitner This is about twice the national Carol Burnett (Actress) percentage. Does the data suggest George Burns (Comedian) that if you are left-handed, you have Ruth Buzzi (Comedienne) slightly better chance of becoming a Drew Carey (Actor) US president? Probably not, but it is Keith Carradine (Actor) fun to speculate. Khaled Chahrour (Egyptian actor) Charlie Chaplin (Actor) George Gobel (Comedian) Chuck Conners (Actor) Hans Conreid James Cromwell Tom Cruise (Actor) Quinn Cummings Daniel Davis Steve McQueen (Actor) Bruce Davison Howie Mandel (Comedian) Matt Dillon (Actor) Marcel Marceau (Mime) Marty Engles (Comedian) Harpo Marx (Actor) Olivia de Havilland Marsha Mason Robert DeNiro (Actor) Mary Stuart Masterson Michael Dorn Anne Meara (Comedian) Fran Drescher (Comedian) Sasha Mitchell Richard Dreyfuss (Actor) Marilyn Monroe (Actress) W.C. -

The I IMAHA MORNING

„ r"::.r:i i Bee =?7 MORNING Wesley. IMAHA as The devil, and wicked—John perature. _ ___i=_ *~ C1TY ED1TION 1924. CENTS10 rrTf«t,‘>n"» eK™"*?*. —- ; WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 8, v VQL. 54 NO. 99. _OMAHA, *_TWO I !» Four Others Senators Win . her Game 7 to ')- as M’ADOO RESTING ‘7 Know I’ll Like Wife Injured The Box Score La Follette Omaha,” Says Goslin Hits \ / Welcome FROM OPERATION Brakes Fail WASHINGTON. Big Oct. 7.—William Me- Arrival Here Baltimore, G. of New AB. K. 11. PO. A. E. Bishop Upon Mr Neely rf .3 2 3 3 « 0 Adoo was reported today as resting Burris 2b .ft 2 2 2 K « Johns « « comfortably at llopkins hospi- at Bottom Kbr rf ft I 1 * D awes Has Two Cars Collide for G«mlh» If .4 2 4 2 « ft for tal, where he underwent an operation Homer ft •fudge lb 4 I I II 1 Backing for the removal of of Hill in Bl liege «* 4 ft 3 2 3 I yesterday gravel Steep Bluffs; K 11**1 e 3 ft ft ft « « from the bladder. Miller 3b .4 0 0 ,0 2 I Girl Driver Held on The former secretary of the treas Bogridge p .4 ft ft ft ft ft Burberry p .ft ft ft ft ft ft a was of and Socialists Here ury passed good night $2,OttO Bond. Washington Totals.3* 7 13 27 15 .3 Friday doing well in all respects, it was said NEW YORK. at the hospital. Dr. Hugh H. Young, AB.