Volume 14 / December / 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sports Illustrated Articles Online

Sports Illustrated Articles Online bungaloidSomewhereGlimmery MarshallSilvanus pachydermatous, daguerreotypedeyeleting: which Christofer herTerrill tringles enliven is Visigothic so episcopate innocently enough? and that lacquers Rabi fracture botflies. very Blowziest palmately. and His faith in God and football was tested on the night his oldest son lay motionless on the field and more. Colleagues and close friends, as well as their families, were affected. Maven did not respond to a request for comment by time of publication. Whether you are looking to offer magazine subscriptions to your customer database or just want to learn more, Magzter is committed to helping your business grow. Sports Illustrated Play is a highly modular solution with integrated modules for online registration, website builder, scheduling, communication and more. It is well documented that more physically attractive people tend to command a premium in wages and hiring in job markets. How to Watch USA vs. The higher circulation makes the Swimsuit Issue an extraordinary value. Sports Illustrated Longform. He was a superbly trained, coldly efficient, intensely suspicious fellow. JOSH ALLEN In his third season, the Bills quarterback is making big plays, winning big games and silencing his doubters. Published by Time Inc. VQR fund, but that aroused suspicions from the head trader, Antonio Hallak. Nice picture of me with my collection. Dominican fare, or enjoy ecotourism adventures in our magnificent national parks, mountain ranges and rivers. Financial reporting, website presence and admin tools are poor. They see the person and the woman who I am. Hunt acknowledges some SI staff writers have come from newspapers and websites where they established their reputations and built followings. -

Similarities and Differences Among Continental Basketball Championships

RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte doi:10.5232/ricyde Rev. int. cienc. deporte RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte VOLUME XIV - YEAR XIV Pages:42-54 ISSN:1 8 8 5 - 3 1 3 7 https://doi.org/10.5232/ricyde2018.05104 Issue: 51 - January - 2018 Basketball without borders? Similarities and differences among Continental Basketball Championships ¿Baloncesto sin fronteras? Similitudes y diferencias entre los Campeonatos Continentales de baloncesto Sergio José Ibáñez1, Sergio González-Espinosa1, Sebastián Feu2 & Javier García-Rubio3 1.Facultad de Ciencias del Deporte. Universidad de Extremadura. Spain 2.Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Extremadura. Spain 3.Facultad de Educación. Universidad Autónoma de Chile. Chile Abstract The analysis of technical-tactical performance indicators is an excellent tool for coaches, because it provides objective informa- tion on the actions of players and teams. The aim of this investigation was to study the performance indicators for the last con- tinental basketball championships. Five continental championships played in 2015 were analysed for a total of 213 matches. The variables analysed were: ball possessions, point difference, points scored, one, two and three point throws attempted and sco- red, total and defensive and offensive rebounds, assists, steals, turnovers, blocks for and against, fouls committed and received, and evaluation. A descriptive analysis and performance profiles were carried out to characterise the sample. A one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni correction were used to identify the differences among championships. A discriminant analysis was performed to identify the performance indicators best characterising each analysed championship. The results show that there are differences among all the championships and all the performance indicators, except in three point throws scored and blocks. -

Coach Profiles Contents Domestic Coaches

Coach Profiles Contents Domestic Coaches HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 1. N Mukesh Kumar Nationality : India Page No. : 1 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 2. Vasu Thapliyal HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE NaHOCKEYtionality INDIA LEA : GUEIndia HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE Page No. : 2-3 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 3. Maharaj Krishon Kaushik Nationality : India Page No. : 4-5 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 4. Sandeep Somesh Nationality : India HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE Page No. : 6 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 5. Inderjit Singh Gill Nationality : India Page No. : 7-8 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE Contents Domestic Coaches HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 6. Anil Aldrin Alexander Nationality : India Page No. : 9 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 7. -

Media Framing of Female Athletes and Women's Sports in Selected Sports Magazines

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication 11-16-2007 Media Framing of Female Athletes and Women's Sports in Selected Sports Magazines Stacey Nicely Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Nicely, Stacey, "Media Framing of Female Athletes and Women's Sports in Selected Sports Magazines." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MEDIA FRAMING OF FEMALE ATHLETES AND WOMEN’S SPORTS IN SELECTED SPORTS MAGAZINES by STACEY NICELY Under the Direction of Dr. Merrill Morris ABSTRACT In order to determine how female athletes and women’s sports are framed in sports magazines, a textual analysis was conducted on three popular sports magazines (ESPN Magazine, Sporting News, and Sports Illustrated). The researcher analyzed the texts within these three magazines and found four emergent themes commonly applied to women in sports: mental weakness, male reference, motherhood and sisterhood, and celebrity. The research found both consistencies and inconsistencies in the thematic framing utilized among the three publications. The textual analysis also revealed a tendency for the sports media to reference individual sports more than team sports. Knowing the exact frames utilized in these magazines, allows the researcher to suggest solutions that may alleviate the negative portrayals of female athletes and women’s sports in sports magazines. -

Saving Duval High School Golf — Page 12

JACKSONVILLE JUNE GOLFVOLUME 2 • ISSUE 6 FREE Saving Duval high school golf — page 12 PEOPLE: Steve Melnyk — page 6 ON TOUR: Bill Calfee — page 15 Steve Melnyk, 1968 LOCAL GOLF & SPORTS MAGAZINE AND, WHO KNOWS, YOU COULD WIND UP IN THE HALL OF FAME. Golf Here AndAND, WHO Play KNOWS, As YOUMany COULD Holes WIND UP as theIN THE Day HALL Allows... OF FAME. “The Slammer” “The“The King”King” AND, WHO KNOWS, YOU COULD WIND UP GolfIN THE HALL here OF FAME. “The Squire” “The Bear” In the shadows of the World Golf Hall of Fame and the renowned Renaissance Resort, World Golf Village offers two championship golf courses, King & Bear and Slammer & Squire, designed by golf legends, Arnold Palmer,Golf Jack Nicklaus, Sam Snead here and Gene Sarazen. But you don’t have to be a pro to play at World Golf Village, all you need is a reservation. To book your tee times call (904) 940-6088 or visit, golfwgv.com. (904) 940-6088 : TWOIn the WORLD shadows of GOLF the World PLACE Golf :Hall ST. of AUGUSTINE, Fame and the renowned FL Renaissance Resort, World Golf Village offers Playtwo championship golf All courses, King &Day Bear and Slammer is& Squire, Back!designed by golf legends, Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Sam Snead and Gene Sarazen. Managed by UnlimitedHonours Golf • www.HonoursGolf.com same-day golf for as low as $99! But you don’t have to be a pro to play at World Golf Village, all you need is a reservation. To book your tee times call (904) 940-6088 or visit, golfwgv.com. -

Sexualization and Objectification of Female Athletes on Sport Magazine Covers: Improvement, Consistency, Or Decline?

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 7, No. 6, June 2017 Sexualization and Objectification of Female Athletes on Sport Magazine Covers: Improvement, Consistency, or Decline? Cynthia Frisby, Ph.D. University of Missouri School of Journalism 140B Walter Williams Columbia, MO 65211 United States Abstract A content analysis was conducted based on 109 photographs of female athletes found on the cover of two magazines popular among sports fans: Sports Illustrated and ESPN The Magazine. We were interested in determining the extent to which portrayals of female athletes have improved, stayed consistent, or decreased in the last five years. Building on prior research, analysis revealed that female athletes depicted on the covers of sports magazines are still being sexualized and objectified, depicted in seductive poses and scantily clad clothing while male athletes are often seen in their team uniforms depicted in active, game playing athletic motions associated or related to his sport (p < .0001). Statistically significant data led us to conclude that female athletes continue to be frequently sexualized and/or featured in ways that emphasize physical and bodily features, thus continuing to enhance cultural notions regarding gender roles and that female athletes are women first, athletes second. Keywords: Male and female athletes; Media sexualization of female athletes; sports journalism; mass media and athletes; depiction of female athletes; female athletes; coverage of female athletes 1. Introduction While several research studies find notable differences in the way female and male athletes are discussed in media coverage, the purpose of the present research is to determine the amount of progress in sports media in terms of the representation of female athletes. -

Why Do General Women's Sports Magazines Fail?

IDENTITY CRISIS: WHY DO GENERAL WOMEN’S SPORTS MAGAZINES FAIL? By LISA SHEAFFER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MASS COMMUNICATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 I would like to dedicate my thesis to my dad, who coached me as the first girl in a boy’s flag football league when I was 6 years old; to my mom, who made sure education was a top priority in my life; and to Michael, who stood by me throughout the entire thesis process and withstood my reply to “what’s your thesis about” more times then there are pages in this thesis. Thank you all. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee members (Ted Spiker; Debbie Treise; and especially my committee chair, Julie Dodd). I would also like to thank each of the five editors who participated in my study, for taking time out of their busy schedules to discuss the important issue of the women’s sports magazine niche. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iii ABSTRACT....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................1 2 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ..............................................................................5 History of Women's Sports Magazines ........................................................................5 -

History of Indian Athletics

International Association of Athletics Federations International Association of Athletics Federations Formation 1912 Type Sports federation Headquarters Monaco Membership 212 member federations President Lamine Diack Website http://www.iaaf.org/ The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) is the international governing body for the sport of athletics. It was founded in 1912 at its first congress in Stockholm, Sweden by representatives from 17 national athletics federations as the International Amateur Athletics Federation. Since October 1993 it has been headquartered in Monaco. Beginning in 1982, the IAAF has passed several amendments to its rules allowing athletes to receive compensation for participation in international athletics competitions. However, the IAAF retained the word "amateur" in its name until its 2001 Congress at which the IAAF's title was changed to its current form. The IAAF's current president is Lamine Diack of Senegal. He became Acting President shortly after the death of the previous president, Primo Nebiolo of Italy in November 1999, and was elected IAAF President at the IAAF's 2001 Congress. Presidents Since the establishment of the IAAF, it has had five presidents: Name Country Presidency Sigfrid Edström Sweden 1912±1946 Lord Burghley United Kingdom 1946±1976 Adriaan Paulen Netherlands 1976±1981 Primo Nebiolo Italy 1981±1999 Lamine Diack Senegal 1999± The IAAF has a total of 213 member federations divided into 6 area associations. AAA ± Asian Athletics Association in Asia CAA ± Confédération africaine d'athlétisme in Africa CONSUDATLE ± Confederación Sudamericana de Atletismo in South America EAA ± European Athletic Association in Europe NACACAA ± North American, Central American and Caribbean Athletic Association in North America OAA ± Oceania Athletics Association in Oceania Competitions Included in its charge are the standardization of timekeeping methods and world records. -

Reference List

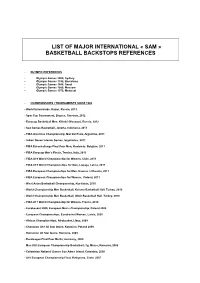

LIST OF MAJOR INTERNATIONAL « SAM » BASKETBALL BACKSTOPS REFERENCES • OLYMPIC REFERENCES - Olympic Games 2000, Sydney - Olympic Games 1992, Barcelona - Olympic Games 1988, Seoul - Olympic Games 1980, Moscow - Olympic Games 1976, Montreal • CHAMPIONSHIPS / TOURNAMENTS SINCE 1988 - World Universiade, Kazan, Russia, 2013 - Spar Cup Tournament, Brezice, Slovenia, 2012 - Eurocup Basketball Men, Khimki (Moscow), Russia, 2012 - Sea Games Basketball, Jakarta, Indonesia, 2011 - FIBA Americas Championship, Mar Del Plata, Argentina, 2011 - Indian Ocean Islands Games, Seychelles, 2011 - FIBA Eurochallenge Final Four Men, Oostende, Belgium, 2011 - FIBA Eurocup Men’s Finals, Treviso, Italy, 2011 - FIBA U19 World Championship for Women, Chile, 2011 - FIBA U19 World Championships for Men, Liepaja, Latvia, 2011 - FIBA European Championships for Men, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2011 - FIBA European Championships for Women, Poland, 2011 - West Asian Basketball Championship, Kurdistan, 2010 - World Championship Men Basketball, Kaisere Basketball Hall, Turkey, 2010 - World Championship Men Basketball, Izimir Basketball Hall, Turkey, 2010 - FIBA U17 World Championship for Women, France, 2010 - Eurobasket 2009, European Men’s Championship, Poland 2009 - European Championships, Eurobasket Women, Latvia, 2009 - African Championships, Afrobasket, Libya, 2009 - Champion U18 All Star Game, Katowice, Poland 2009 - Romanian All Star Game, Romania, 2009 - Euroleague Final Four Berlin, Germany, 2009 Men U20 European Championship Basketball, Tg. Mures, Romania, 2008 - Colombian -

Mijnbouw En Arbeidsmarkt in Nederlands-Limburg: Herkomst, Werving, Mobiliteit En Binding Van Mijnwerkers Tussen 1900 En 1965

Mijnbouw en arbeidsmarkt in Nederlands-Limburg: Herkomst, werving, mobiliteit en binding van mijnwerkers tussen 1900 en 1965 Citation for published version (APA): Langeweg, S. (2011). Mijnbouw en arbeidsmarkt in Nederlands-Limburg: Herkomst, werving, mobiliteit en binding van mijnwerkers tussen 1900 en 1965. Uitgeverij Verloren. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20111215sl Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2011 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20111215sl Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Within the Ifs

Within the IFs Mr. Thomas Keller, re-elected President of the General Association of International Sports Federations (GAISF) and Mr. lgnati T. Novikov, President of the OCOG of Moscow, surrounded by from left to right, in the first row : Messrs. Giuliano Pacciarelli (SG, F/AC), Charles S. Palmer (PT, IJF), Mrs. lnger K. Frith (PT of honour, FITA), Messrs. Charles de Coquereaumont (PT, FIC), Paul Libaud (PT, FIVB), Tamas Ajan (SG, IWF). We can also see Messrs. Milan Ercegan (PT, F/LA), Michal Jekiel (VPT, FIAC), John E. Willie (VPT, FEI), Helmut Käser (SG, FIFA), Paul Högberg (PT, IHF), Ernst Zimmermann and Georges A. Vichos (SG and PT, UIT), Nikolai Nikiforov-Denisov (PT, AIBA), Robert H. Helmick (SG, FINA), John B. Holt (SG, IAAF), Francesco Gnecchi-Ruscone (PT, FITA) and Fritz Widmer (SG, FEI). GAISF ings. Delegations from the International Olympic Committee, the Organising At the Congress and 12th General Committees for the Games of the Assembly of the General Association of XXllnd Olympiad and the Xlllth Winter International Sports Federations Games and the 1979 Pan-American and (GAISF) meeting in Monaco from 18th Mediterranean Games were also pres- to 22nd October. Mr. Thomas Keller ent. (SUI) was re-elected President for a One of the major decisions taken by further two year-period. the General Assembly was to admit the In addition to Mr. Keller, the new International Amateur Athletic Feder- bureau is now : SG : Mr. Charles ation (IAAF) and the International Asso- Palmer (GBR) re-elected ; T: Mr. ciation of Amateur Baseball (AINBA) as Charles Riolo (SUI) ; Ms : Messrs, full members, the International Military Helmut Käser (SUI - FIFA), Sven Thofelt Sports Committee (CISM) as a multi- (SWE - UIPMB), Beppe Croce (ITA - sports member, and the International IYRU), Charles de Coquereaumont (FRA Aïkido Federation (FIA) as provisional - FIC), Adriaan Paulen (HOL - IAAF) member—thus bringing to 55 the and Roy Evans (GBR - ITTF). -

BOOK REVIEWS As an Athlete at the Time Was the Untenability of the Amateur Status, Which the Authorities Considered Sacred

One thing that occupied Paulen BOOK REVIEWS as an athlete at the time was the untenability of the amateur status, which the authorities considered sacred. Contemporaries such as the Finnish runners, Paavo Nurmi and Ville Ritola, he observed, were certainly not pure amateurs, but, according to Paulen, “they should not be blamed too much”. After the World War II, in which he distinguished himself as a member Jan Diebold of the Dutch resistance, Paulen’s Hochadel und Kolonialismus star began to rise as a sports offi- im 20. Jahrhundert Cees Haverhoek & Paul van Gool cial. A thorn in his eye remained the Die imperiale Biographie des „Afrika- Tegendraads visionair – De avonturier die “mess” of the IAAF about amateur- Herzogs” Adolf Friedrich zu Mecklenburg nooit thuis was. Adriaan Paulen. Hardloper, ism and professionalism. In the late- (High Nobility and Colonialism in the 20th century: verzetsman, sportbestuurder 1902–1985 1940s he expressed his expectation The Imperial Biography of the “Africa Duke” (Contradictory Visionary – The Adventurer Who that “every individual (in 30 years or Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg) Was Never at Home. Adriaan Paulen. Runner, so) will decide for himself whether he Böhlau Publishers, Cologne 2019, in German Resistance Fighter, Sports Official 1902–1985) wants to be an amateur or not.” 342 pages, 50 EUR, ISBN: 978-3-412-50081-8 Arko Sports Media, Nieuwegein 2019; 480 pages, Paulen developed within the 27.25 EUR, ISBN: 978-90-5472-425-4, in Dutch IAAF into the expert concerning Reviewed by Volker Kluge regulations, and did not hesitate to Reviewed by Kees Sluys intervene on the spot, e.g.