Appendix 1: Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organised Crime Around the World

European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI) P.O.Box 161, FIN-00131 Helsinki Finland Publication Series No. 31 ORGANISED CRIME AROUND THE WORLD Sabrina Adamoli Andrea Di Nicola Ernesto U. Savona and Paola Zoffi Helsinki 1998 Copiescanbepurchasedfrom: AcademicBookstore CriminalJusticePress P.O.Box128 P.O.Box249 FIN-00101 Helsinki Monsey,NewYork10952 Finland USA ISBN951-53-1746-0 ISSN 1237-4741 Pagelayout:DTPageOy,Helsinki,Finland PrintedbyTammer-PainoOy,Tampere,Finland,1998 Foreword The spread of organized crime around the world has stimulated considerable national and international action. Much of this action has emerged only over the last few years. The tools to be used in responding to the challenges posed by organized crime are still being tested. One of the difficulties in designing effective countermeasures has been a lack of information on what organized crime actually is, and on what measures have proven effective elsewhere. Furthermore, international dis- cussion is often hampered by the murkiness of the definition of organized crime; while some may be speaking about drug trafficking, others are talking about trafficking in migrants, and still others about racketeering or corrup- tion. This report describes recent trends in organized crime and in national and international countermeasures around the world. In doing so, it provides the necessary basis for a rational discussion of the many manifestations of organized crime, and of what action should be undertaken. The report is based on numerous studies, official reports and news reports. Given the broad topic and the rapidly changing nature of organized crime, the report does not seek to be exhaustive. -

Discursos Frente a La Migración Y Teorías De

Horacio Aarón Saavedra Archundia Superando las Fronteras del Discurso Migratorio: los Conceptos de las Teorías de las Relaciones Internacionales en la Aceptación y el Rechazo de los Indocumentados Mexicanos a partir de la Era del NAFTA Jenseits des Migrationsdiskurses: Theoriekonzepte der Internationalen Beziehungen zur Aufnahme bzw. Ablehnung der so genannten ―illegalen mexikanischen Einwanderer― im Zeitalter der NAFTA Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Sozialwissenschaften in der Fakultät für Sozial- und Verhaltenswissenscahften der Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen 2008 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung der Fakultät für Sozial- und Verhaltenswissenschaften der Universität Tübingen Hauptberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Andreas Boeckh Mitberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Hans-Jürgen Burchardt Dekan: Prof. Dr. Ansgar Thiel Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 30.09.2008 Universitätsbibliothek Tübingen 1 Indice General Introducción ............................................................................................................. 4 1. Revisión histórica: antecedentes de la concepción del migrante en Estados Unidos ................................................................................................................. 19 2. Revisión teórica: paradigmas internacionales, ................................................ 46 3. Los agentes políticos de EU en la primera década de vigencia del TLCAN: las éticas del guerrero, tendero y profeta ............................................................... 78 4. Caso de estudio -

Community, Identity, and Spatial Politics in San Francisco Public Housing, 1938--2000

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2005 "More than shelter": Community, identity, and spatial politics in San Francisco public housing, 1938--2000 Amy L. Howard College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Public Policy Commons, United States History Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Howard, Amy L., ""More than shelter": Community, identity, and spatial politics in San Francisco public housing, 1938--2000" (2005). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623466. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-7ze6-hz66 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. Furtherowner. reproduction Further reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. “MORE THAN SHELTER”: Community, Identity, and Spatial Politics in San Francisco Public Housing, 1938-2000 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Amy Lynne Howard 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

Art Agnos Papers, 1977-2002 (Bulk 1984-1991)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1x0nf1tk Online items available Finding Aid to the Art Agnos Papers, 1977-2002 (bulk 1984-1991) Finding aid prepared by Tami J. Suzuki. San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA, 94102 (415) 557-4567 [email protected] January 2012 Finding Aid to the Art Agnos SFH 46 1 Papers, 1977-2002 (bulk 1984-1991) Title: Art Agnos papers Date (inclusive): 1977-2002 Date (bulk): 1984-1991 Collection Identifier: SFH 46 Creator: Agnos, Art, 1938- Creator: Bush, Larry, 1946- Physical Description: 76 boxes(73.8 cubic feet) Contributing Institution: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA 94102 (415) 557-4567 [email protected] Abstract: This collection documents the political career of Art Agnos, who represented the 16th district in the California Assembly from 1976 to 1988 and was mayor of San Francisco from 1988-1992. Physical Location: The collection is stored off-site. Language of Materials: Collection materials are mainly in English. Some press clippings are in Greek. Access The collection is open for research. A minimum of two working days' notice is required for use. Photographs can be viewed during the Photograph Desk hours. Call the San Francisco History Center for hours and information at 415-557-4567 Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the City Archivist. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the San Francisco Public Library as the owner of the physical items. -

Extensions of Remarks E67 HON. DAVID M. Mcintosh HON. LEE H

February 3, 1998 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E67 Francisco, and Joe Alioto was a product of that convulsed a number of other major Amer- ANDERSON HIGH SCHOOL INDIANS that culture. The son of a Sicilian immigrant ican cities at that time. Jerry Carroll and Wil- BASKETBALL TEAM fish wholesaler, he was born in 1916 in North liam Carlsen in The San Francisco Chronicle Beach and grew up in that area. He attended said his legacy as mayor was ``an explosion of HON. DAVID M. McINTOSH San Francisco schoolsÐGarfield and Salesian downtown growth that changed the city's sky- OF INDIANA Schools and then Sacred Heart High School. line, helped cement San Francisco as a player IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES He graduated from St. Mary's College in on the Pacific Rim and stirred up the neigh- Tuesday, February 3, 1998 Moraga, and then received a law degree from borhoods in a way that has altered the city's Catholic University of America in Washington, political landscape to this day.'' Mr. Mc. MCINTOSH. Mr. Speaker, I want to D.C. take this opportunity to recognize the boys' As an attorney, Joe Alioto had a highly suc- He seized national attention as San Francis- varsity basketball team of Anderson High cessful career, both before and after his two co's mayor. In 1968, just a few months after School. These distinguished and courageous terms as Joe Alioto's mayor. After completing he was elected mayor, he was considered a young men traveled to Washington D.C. and law school in our nation's capitol, he accepted leading candidate as runningmate of Demo- won an exciting game against Dematha High a position in the Antitrust Division of the U.S. -

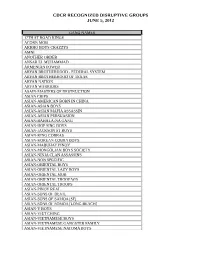

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

Management Strategies in Disturbances and with Gangs/Disruptive Groups APR ,::; F992 L

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. u.s. Department of Justice National Institute of Corrections Management Strategies in Disturbances and with Gangs/Disruptive Groups APR ,::; f992 l Management Strategies in Disturbances and with Gangs/Disruptive Groups October 1991 136184 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this 9 J : 'lIM' II> material has been granted by, • IN Pub11C Dcmam Ie u. S. Department of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside 01 the NCJRS system requires permission of the.sl ASt owner. ---- ---- ------1 PREFACE Prison disturbances range from minor incidents that disrupt institution routine to major disturbances that involve a large proportion of inmates and threaten security and safety. Realizing that proactive management strategies and informed readiness can reduce the potential damage of prison disturbances, many departments of corrections are seriously addressing the need both to prevent and to plan for managing such disturbances. Administrators are also looking for better ways to avert the potentially violent activities and serious problems caused by prison gangs and organized groups. In response to the need for improved, current information on how corrections departments might prepare themselves to deal with the problems of both gangs and disturbances, the NIC Prisons Division and the NIC National Academy of Corrections sponsored special issue seminars entitled "Management Strategies in Disturbances and with Gangs/Disruptive Groups" in Boulder, Colorado, and in Baltimore, Maryland. -

Latinidad En Encuentro

Latinidad en encuentro : experiencias migratorias en los Estados Unidos Titulo Albo Díaz, Ana Niria - Compilador/a o Editor/a; Aja Díaz, Antonio - Compilador/a o Autor(es) Editor/a; La Habana Lugar Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas Editorial/Editor 2014 Fecha Cuadernos Casa no. 49 Colección Literatura; Migración; Latinos; Artes visuales; América Latina; Estados Unidos; Temas Libro Tipo de documento "http://biblioteca.clacso.org/Cuba/casa/20200419105329/Latinidad-en-encuentro.pdf" URL Reconocimiento-No Comercial-Sin Derivadas CC BY-NC-ND Licencia http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.es Segui buscando en la Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO http://biblioteca.clacso.org Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO) Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (CLACSO) Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) www.clacso.org Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas LATINIDAD EN ENCUENTRO.indd 2 12/03/2014 14:04:07 Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas LATINIDAD EN ENCUENTRO.indd 3 12/03/2014 14:04:07 Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas LATINIDAD EN ENCUENTRO.indd 5 12/03/2014 14:04:08 Edición: Yariley Hernández Diseño: Ricardo Rafael Villares Ilustración de cubierta: Nelson Ponce Realización computarizada: Marlen López Martínez Alberto Rodríguez Todos los derechos reservados © Sobre la presente edición: Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas, 2014 ISBN 978-959-260-413-1 Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas FONDO EDITORIAL CASA DE LAS AMÉRICAS casa 3ra y G, El Vedado, La Habana [email protected] www.casa.cult.cu. LATINIDAD EN ENCUENTRO.indd 6 12/03/2014 14:04:08 Introducción Las oleadas crecientes de personas que llegan a los Estados Unidos a través de los caminos, que ahora no conducen a Roma sino a otro imperio, no escapan al entramado de experiencias transnacionales que estos desplazamientos conllevan. -

149300NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. t I • CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE DANIEL E. LUNGREN Attorney General GREGORY G. COWART, Director DMSION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT CHARLES C. HARPER, Deputy Director DMSION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT • BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION ROBERT J. LUCA, Chief Whitt Murray, Assistant Chief Charles C. Jones, Special Agent In Charge, Intelligence Operations Kirby T. Vickery, Manager, Investigative and Support Services Jerry Marynik, Gangs 2000 Project Coordinator " Supervisor, Gangs/Criminal Extremists Unit " 4949 Broadway P.O. Box 163029 • Sacramento, CA 95816-3029 • 149300 U.S. Department of Justice Natlonallnstltute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactiy as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or op!nlons stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or pOlicies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been ge~1rfornia Dept. of Justice to the Ni',tional Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyrighl owner. • '\ • PREFACE • This report is an effort to give the reader a sobering glimpse of the future regarding criminal street gang crime and violence in California. The report attempts to assess the current gang situation and forecast gang trends for the year 2000. Criminal street gang members are terrorizing communities throughout California where the viciousness of the gangs have taken away many of the public's individual freedoms. In some parts of the state, gang members completely control the community where they live and commit their violent crimes. -

![Justice Robert Dossee [Robert Dossee 6051.Doc]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5162/justice-robert-dossee-robert-dossee-6051-doc-2295162.webp)

Justice Robert Dossee [Robert Dossee 6051.Doc]

California Appellate Court Legacy Project – Video Interview Transcript: Justice Robert Dossee [Robert_Dossee_6051.doc] Timothy Reardon: I’m Justice Timothy A. Reardon, R-E-A-R-D-O-N, Associate Justice, California Court of Appeal, Division Four. Robert Dossee: Justice Robert L. Dossee, that’s spelled D-O-S-S-E-E, Retired Associate Justice, California Court of Appeal. David Knight: Justice Reardon, I’m ready when you are. Timothy Reardon: Today’s date is June 5, 2007. This interview is being conducted as part of the Appellate Court Legacy Project, the purpose of which is to create an oral history of the appellate courts in California through a series of interviews of retired justices who have served on our court. I’m Tim Reardon, an Associate Justice of the First District Court of Appeal. We’re honored to have with us today the Honorable Robert L. Dossee, who served on the First District from 1990 to 1998. Welcome, Bob, and thank you for participating. Robert Dossee: Thanks, Tim. Thanks for having me. Timothy Reardon: All right. Bob, you’re a native San Franciscan and you still reside in the city. Can you tell us a little bit about the Dossee family and growing up in the Excelsior district of San Francisco? Robert Dossee: Sure. Let’s start at the beginning. My great-grandfather came over from northern Germany; it was actually part of Prussia at that time, in 1852, and settled in the San Jose area. My mom, my dad, all my grandparents were born in the San Jose area. -

Politics of Crime in the 1970'S: a Two City Comparison

Document Title: Politics of Crime in the 1970’s: A Two City Comparison Author(s): Stephen C. Brooks Northwestern University Center for Urban Affairs Document No.: 82420 Date Published: 1980 Award Title: Reactions to Crime Project Award Number: 78-NI-AX-0057 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. POLITICS OF CREE IN THE 1;920s: A TWO CI!R COMPARISON Stephen C. Brooks Center for Urban Affairs Northwestern University Evanston, IL 60201 June 1980 Prepared under Grant Number 78-NI-AX-0057 from the National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. PREFACE The research described here was conducted while I was a Research Fellow at the Center for Urban Affairs, Northwestern University. I am grateful to all those at the Center for making such research opportunities available and am especially grateful to the staff of the Reactions to Crime Project who assisted me. I received very helpful comments from those who read all or parts of this manuscript; Ted Robert Gurr, Herbert Jacob, Dan Lewis, Michael Maxfield and Armin Rosencranz.