Alpine Experiments: the National Parks and the Development of Skiing in the American West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sidecountry Is Backcountry

Sidecountry is Backcountry By Doug Chabot Carve, February 2013 For many resort skiers, the word “sidecountry” has become a standard definition of backcountry terrain adjacent to a ski area. Usually the acreage on the other side of the boundary is administered by the US Forest Service and the ski area becomes a convenient jumping off point to access public lands. In the last few years skiers have overwhelmingly embraced this access as the in-bound crowds ski up new snow at a ferocious pace. Untracked powder is a dwindling resource, an addictive drug, and access gates are the needle in a vein to a quick fix. Some resorts use sidecountry as a marketing scheme to draw customers. Similarly, hard goods manufacturers sell specific clothing and skis aimed at sidecountry users. As in any marketing campaign, the upside is enhanced (“Face shots for everyone!”), while the downsides are hidden (“I’m sorry to inform you your son has died in an avalanche”). Sidecountry users are a distinct group. They are not backcountry skiers and riders nor are they strictly in bounds users. But avalanches are an equal opportunity killer and don’t care if you are on a snowmobile, snowboard, fat skis, touring gear or snowshoes. Avalanches don’t care if you’ve just ridden a lift and ducked the boundary rope or entered through a gate. Every year the world over, weak layers form in the snowpack, slabs form on top of these layers and when the balance is precarious, people trigger avalanches. Sometimes these slides release just spitting distance from a ski area boundary. -

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

The Russians Are the Fastest in Marathon Cross-Country Skiing: the (Engadin Ski Marathon)

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2017, Article ID 9821757, 7 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9821757 Research Article The Russians Are the Fastest in Marathon Cross-Country Skiing: The (Engadin Ski Marathon) Pantelis Theodoros Nikolaidis,1,2 Jan Heller,3 and Beat Knechtle4,5 1 Exercise Physiology Laboratory, Nikaia, Greece 2Faculty of Health Sciences, Metropolitan College, Athens, Greece 3Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 4Gesundheitszentrum St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland 5Institute of Primary Care, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Correspondence should be addressed to Beat Knechtle; [email protected] Received 20 April 2017; Accepted 17 July 2017; Published 21 August 2017 Academic Editor: Laura Guidetti Copyright © 2017 Pantelis Theodoros Nikolaidis et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. It is well known that athletes from a specific region or country are dominating certain sports disciplines such as marathon running or Ironman triathlon; however, little relevant information exists on cross-country skiing. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the aspect of region and nationality in one of the largest cross-country skiing marathons in Europe, the “Engadin Ski Marathon.” All athletes ( = 197,125) who finished the “Engadin Ski Marathon” between 1998 and 2016 were considered. More than two-thirds of the finishers (72.5% in women and 69.6% in men) were Swiss skiers, followed by German, Italian, and French athletes in both sexes. Most of the Swiss finishers were from Canton of Zurich (20.5%), Grisons (19.2%), and Berne (10.3%). -

Intermediate Ski Curriculum ------Which Group Should I Join? (Skills and Fitness)

New Mexico Cross Country Ski Club Intermediate Ski Curriculum ----------------------------------- Which group should I join? (skills and fitness) Ask yourself: “Am I comfortable snow plow turning on a slope and doing step turns?” If the answer is “no,” stick with the beginners. That's just what the beginner group will practice. If the answer is “yes” and you think you are an intermediate student, “Have I skied for most of a day, 5 miles or more?” You should be fit enough to be out all-day, ski six miles & do some work up and down hills. Why Learn Intermediate Skills?: When people learn downhill (alpine) skiing, they usually learn that only beginners snowplow, and once you move beyond beginner level, you parallel ski and no longer snow plow. This is NOT true for cross-country and back- country skiing. Please check this attitude at the door. Cross-country & back-country means having options & making choices, depending on conditions & terrain. Just because someone can parallel or telemark turn doesn't mean they don't snow plow when necessary. A skilled cross-country or back-country skier has a repertoire of turns and skills. For example, on a mountainous back-country tour or hut trip when a trail is narrow or icy or steep or trees are close and skiers carry heavy packs, to descend treacherous places they may snowplow, use kick-turns, or make a wide traverse instead of going down the fall line. When the legs are tired or the snow very deep, skiers may use techniques such as parallel or use step turns. -

Economic Contributions of Winter Sports in a Changing Climate

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Earth Systems Research Center Space (EOS) Winter 2-23-2018 Economic Contributions of Winter Sports in a Changing Climate Hagenstad Consulting, Inc. Elizabeth Burakowski USNH, [email protected] Rebecca Hill Colorado State University - Fort Collins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/ersc Part of the Climate Commons, Recreation Business Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Hagenstad, M., E.A. Burakowski, and R. Hill. 2018. Economic Contributions of Winter Sports in a Changing Climate. Protect Our Winters, Boulder, CO, USA. Feb. 23, 2018. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Earth Systems Research Center by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTIONS OF WINTER SPORTS IN A CHANGING CLIMATE FEBRUARY 2018 MARCA HAGENSTAD, M.S. ELIZABETH BURAKOWSKI, M.S., PH.D. REBECCA HILL, M.S., PH.D. PHOTO: JOHN FIELDER PREFACE CLIMATE ECONOMICS AND THE GYRO MAN PROTECT OUR WINTERS BOARD MEMBER AUDEN SCHENDLER One night this December, I walked back to my hotel after the annual Powder Awards in Breckenridge. It was one of the driest and warmest starts to the Colorado ski season in memory. Having missed dinner, and being, well, a skier, I had spent four hours drinking Moscow mules and beer, growing increasingly hungry, but taking energy from the community feeling of the event. -

Oregon Tourism Commission

Oregon Tourism Commission Staff Report | April 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Optimize Statewide Economic Impact............................................................................... 2 Drive business from key global markets through integrated sales/marketing plans leveraged with global partners and domestic travel trade ..................................................... 2 Facilitate the development of world-class tourism product in partnership with community leaders, tourism businesses and key agencies .................................................... 7 Guide tourism in a way that achieves the optimal balance of visitation, economic impact, natural resources conservation and livability ....................................................................... 10 Inspire overnight leisure travel through industry-leading branding, marketing and communications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Support and Empower Oregon’s Tourism Industry ...................................................... 39 Provide development and training opportunities to meet the evolving tourism industry needs ......................................................................................................................................... 39 Implement industry leading visitor information network ................................................... 46 Fully realize statewide, strategic integration of OTIS (Oregon Tourism Information System) ................................................................................................................................... -

Understanding the New Market: NSAA's Millennial Study

Understanding the New Market: NSAA’s Millennial Study 2015 ISKINY – PSAA Expo Lake Placid Conference Center September 22nd, 2015 Before we begin, some ground rules. Don’t Confuse Societal Trends with Generational Trends Don’t Life Stage Differences for with Generational Differences And remember, this is more about us than them What’s all the fuss? The Birth of the Teenager in the 20th Century The 21st Century Brings the Concept of the “Emerging Adult” Five Milestones: • Completing School • Leaving Home • Becoming Financially Independent • Marrying • Having a Child In the recent past the majority had hit all of these goals by age 30, today very few have reached these goals by age 30, nor would some find it desirable to do so. Millennials: • Born after 1980. • Currently age 35 and under. • 18-35 year olds are 24.5% of population. Size of Age Range in 2004 vs. 2014 30 2004 Over 9M more people 25.5 25 2014 in this age category 23.0 than in 2004 21.7 20 17.9 17.9 15.9 15 12.4 13.2 10 Population (in (in millions) Population 5 0 18 to 20 21 to 24 25 to 29 30 to 35 Age Range: Size of Cohort Accounted for by Age Group and Percent Non- White, Non-hispanic within Age Group: 2014 50% 50% 44% 44% 45% 43% 42% 45% 40% 40% Percent of Current Cohort 35% Percent Non-White or Hispanic 33% 35% 30% 28% 30% Waiting for 2042 25% 23% 25% 20% 20% 17% Percent Minority Percent Percent of Cohort Percent 15% 15% 10% 10% 5% 5% 0% 0% 18 to 20 21 to 24 25 to 29 30 to 35 Age Group: Percent of Total Population in 2014 9% 8.0% 8% Overall 24.5% of Total U.S. -

![VOICE of HIMALAYA 5 G]Kfn Kj{Tlo K|Lzif0f K|Lti7fgsf] Cfly{S Jif{ )&@÷)&# Sf] Jflif{S Ultljlw Kl/Ro Lgodfjnl, @)%( /X]Sf] 5](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4303/voice-of-himalaya-5-g-kfn-kj-tlo-k-lzif0f-k-lti7fgsf-cfly-s-jif-%C3%B7-sf-jflif-s-ultljlw-kl-ro-lgodfjnl-x-sf-5-604303.webp)

VOICE of HIMALAYA 5 G]Kfn Kj{Tlo K|Lzif0f K|Lti7fgsf] Cfly{S Jif{ )&@÷)&# Sf] Jflif{S Ultljlw Kl/Ro Lgodfjnl, @)%( /X]Sf] 5

ljifoqmd ;Dkfbg d08n kj{tLo kj{tf/f]x0fsf] k|d'v s]Gb| nfSkf k'm6L z] kf{ k]Daf u]Nh] z]kf{ aGb}5 k|lti7fg 5 pQdafa' e§/fO{ g]kfn kj{tLo k|lzIf0f k|lti7fgsf] cfly{s jif{ )&@÷)&# sf] jflif{s ultljlw 6 ;Dkfbs xfdLn] k|lti7fgnfO{ kj{tLo kj{tf/f]x0fsf] /fli6«o o'j/fh gof“3/ ] k|lti7fgsf] ?kdf ljsl;t ul/;s]sf 5f}+ 12 Adventure Tourism: Joj:yfks Understanding the Concept, / f] dgfy 1jfnL Recognizing the Value 16 g]kfndf :sLsf] ;Defjgf 5 eg]/ g]kfnL se/ tyf n]–cfp6 ;dfhs} ;f]r abNg' h?/L 5 43 l:k8 nfOg lk|G6;{ k|f= ln= s0ff{nLdf ko{6gsf] ljljwtf afnfh'–!^, sf7df8f} F 49 x'6' cyf{t\ /f/f 56 d'b|0f s0ff{nLsf kxf8 klg af]N5g\ 58 k"0f{ lk|lG6Ë k|]; Strategic Development nug6f]n, sf7df8f}F Plan of Nepal Mountain Academy 2016-2021 60 k|sfzs Ski Exploration Report Mustang/ g] kfn ;/ sf/ Mera Peak 93 ;+:s[lt, ko{6g tyf gful/ s p8\8og dGqfno Ski Exploration Report Khaptad 112 g]kfn kj{tLo k|lzIf0f k|lti7fg SKI COURSE - 2016 LEVEL-2 124 rfkfufpF /f]8 -;ftbf]af6f] glhs_ 6'6]kfgL, SKI COURSE - 2016 LEVEL-1 156 nlntk'/, g]kfn xfd|f lxdfn kmf]6f] lvRgsf kmf] g M ))(&&–!–%!%!(!%, %!%!()$ Website: www.man.gov.np nflu dfq} xf]Ogg\ 176 Email: [email protected] kfx'gfsf] kvf{Odf s0ff{nL 185 k|sfzsLo kj{tLo kj{tf/f]x0fsf] k|d'v s]Gb| aGb}5 k|lti7fg k|s[ltn] ;DkGg d'n's xf] g]kfn . -

Grand Canyon; No Trees As Large Or As the Government Builds Roads and Trails, Hotels, Cabins GASOLINE Old As the Sequoias

GET ASSOCIATED WITH SMILING ASSOCIATED WESTERN DEALERS NATIONAL THE FRIENDLY SERVICE r OF THE WEST PARKS OUR NATIONAL PARKS "STATURE WAS GENEROUS first, and then our National sunny wilderness, for people boxed indoors all year—moun Government, in giving us the most varied and beautiful tain-climbing, horseback riding, swimming, boating, golf, playgrounds in all the world, here in Western America. tennis; and in the winter, skiing, skating and tobogganing, You could travel over every other continent and not see for those whose muscles cry for action—Nature's loveliness as many wonders as lie west of the Great Divide in our for city eyes—and for all who have a lively curiosity about own country . not as many large geysers as you will find our earth: flowers and trees, birds and wild creatures, here in Yellowstone; no valley (other nations concede it) as not shy—and canyons, geysers, glaciers, cliffs, to show us FLYING A strikingly beautiful as Yosemite; no canyon as large and how it all has come to be. vividly colored as our Grand Canyon; no trees as large or as The Government builds roads and trails, hotels, cabins GASOLINE old as the Sequoias. And there are marvels not dupli and camping grounds, but otherwise leaves the Parks un touched and unspoiled. You may enjoy yourself as you wish. • cated on any scale, anywhere. Crater Lake, lying in the cav The only regulations are those necessary to preserve the ity where 11 square miles of mountain fell into its own ASSOCIATED Parks for others, as you find them—and to protect you from MAP heart; Mt. -

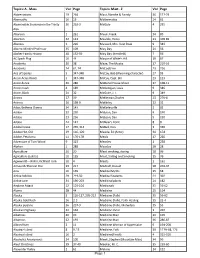

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Yosemite Forest Dynamics Plot

REFERENCE COPY - USE for xeroxing historic resource siuay VOLUME 3 OF 3 discussion of historical resources, appendixes, historical base maps, bibliography YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK / CALIFORNIA Historic Resource Study YOSEMITE: THE PARK AND ITS RESOURCES A History of the Discovery, Management, and Physical Development of Yosemite National Park, California Volume 3 of 3 Discussion of Historical Resources, Appendixes, Historical Base Maps, Bibliography by Linda Wedel Greene September 1987 U.S. Department of the Interior / National Park Service b) Frederick Olmsted's Treatise on Parks ... 55 c) Significance of the Yosemite Grant .... 59 B. State Management of the Yosemite Grant .... 65 1. Land Surveys ......... 65 2. Immediate Problems Facing the State .... 66 3. Settlers' Claims ........ 69 4. Trails ........%.. 77 a) Early Survey Work ....... 77 b) Routes To and Around Yosemite Valley ... 78 c) Tourist Trails in the Valley ..... 79 (1) Four-Mile Trail to Glacier Point ... 80 (2) Indian Canyon Trail ..... 82 (3) Yosemite Fall and Eagle Peak Trail ... 83 (4) Rim Trail, Pohono Trail ..... 83 (5) Clouds Rest and Half (South) Dome Trails . 84 (6) Vernal Fall and Mist Trails .... 85 (7) Snow Trail ....... 87 (8) Anderson Trail ....... (9) Panorama Trail ....... (10) Ledge Trail 89 5. Improvement of Trails ....... 89 a) Hardships Attending Travel to Yosemite Valley . 89 b) Yosemite Commissioners Encourage Road Construction 91 c) Work Begins on the Big Oak Flat and Coulterville Roads ......... 92 d) Improved Roads and Railroad Service Increase Visitation ......... 94 e) The Coulterville Road Reaches the Valley Floor . 95 1) A New Transportation Era Begins ... 95 2) Later History 99 f) The Big Oak Flat Road Reaches the Valley Floor . -

Performance Parameters in Competitive Alpine Skiing Disciplines of Slalom, Giant Slalom and Super-Giant Slalom

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Performance Parameters in Competitive Alpine Skiing Disciplines of Slalom, Giant Slalom and Super-Giant Slalom Lidia B. Alejo 1,2 , Jaime Gil-Cabrera 1,3, Almudena Montalvo-Pérez 1 , David Barranco-Gil 1 , Jaime Hortal-Fondón 1 and Archit Navandar 1,* 1 Faculty of Sports Sciences, Universidad Europea de Madrid, C/Tajo, s/n, 28670 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (L.B.A.); [email protected] (J.G.-C.); [email protected] (A.M.-P.); [email protected] (D.B.-G.); [email protected] (J.H.-F.) 2 Instituto de Investigación Hospital 12 de Octubre (imas12), 28041 Madrid, Spain 3 Royal Spanish Winter Sports Federation, 28703 San Sebastian de los Reyes, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The objective of this study was to describe the kinematic patterns and impacts in male and female skiers in the super-giant slalom, giant slalom and slalom disciplines of an international alpine skiing competition using a portable Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) technology device. Fifteen skiers (males, n = 9, females, n = 6) volunteered to participate in this study. Data acquisition was carried out using a wireless inertial measurement device (WIMUTM PRO: hybrid location system GNSS at 18 Hz with a precision locator UltraWideband UWD (<10 cm) and 3D accelerometers 1000 Hz) where distances covered in different speed and acceleration thresholds and Citation: B. Alejo, L.; Gil-Cabrera, J.; impacts above 5g were recorded in each of the disciplines. Male and female alpine skiers showed Montalvo-Pérez, A.; Barranco-Gil, D.; different physical parameters and impacts even though they competed in the same courses in the Hortal-Fondón, J.; Navandar, A.