MAKING MEANING out of MOUNTAINS: SKIING, the ENVIRONMENT and ECO-POLITICS by MARK CHRISTOPHER JOHN STODDART M.A., University Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sidecountry Is Backcountry

Sidecountry is Backcountry By Doug Chabot Carve, February 2013 For many resort skiers, the word “sidecountry” has become a standard definition of backcountry terrain adjacent to a ski area. Usually the acreage on the other side of the boundary is administered by the US Forest Service and the ski area becomes a convenient jumping off point to access public lands. In the last few years skiers have overwhelmingly embraced this access as the in-bound crowds ski up new snow at a ferocious pace. Untracked powder is a dwindling resource, an addictive drug, and access gates are the needle in a vein to a quick fix. Some resorts use sidecountry as a marketing scheme to draw customers. Similarly, hard goods manufacturers sell specific clothing and skis aimed at sidecountry users. As in any marketing campaign, the upside is enhanced (“Face shots for everyone!”), while the downsides are hidden (“I’m sorry to inform you your son has died in an avalanche”). Sidecountry users are a distinct group. They are not backcountry skiers and riders nor are they strictly in bounds users. But avalanches are an equal opportunity killer and don’t care if you are on a snowmobile, snowboard, fat skis, touring gear or snowshoes. Avalanches don’t care if you’ve just ridden a lift and ducked the boundary rope or entered through a gate. Every year the world over, weak layers form in the snowpack, slabs form on top of these layers and when the balance is precarious, people trigger avalanches. Sometimes these slides release just spitting distance from a ski area boundary. -

Rules for Orienteering USA Sanctioned Events March, 2018

March 16, 2018 Rules for Orienteering USA Sanctioned Events March, 2018 Table of Contents A Rules for Foot Orienteering Events ................................................................................................... 5 A.1 Application and Enforcement of the Rules .............................................................................................. 5 A.2 Definitions ................................................................................................................................................ 5 A.3 Classification of Competitions ................................................................................................................. 5 A.4 Sanctioning .............................................................................................................................................. 6 A.5 Key Personnel .......................................................................................................................................... 7 A.6 Reports and Fees ..................................................................................................................................... 8 A.7 Secrecy and Embargo ............................................................................................................................... 8 A.8 Event Announcements ............................................................................................................................. 8 A.9 Orienteering USA Calendar ..................................................................................................................... -

Avalanche Information for Subscribers

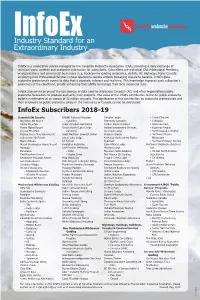

InfoEx Industry Standard for an Extraordinary Industry InfoEx is a cooperative service managed by the Canadian Avalanche Association (CAA), providing a daily exchange of technical snow, weather and avalanche information for subscribers. Subscribers are individual CAA Professional Members, or organizations and commercial businesses (e.g. backcountry guiding companies, ski hills, BC Highways, Parks Canada) employing CAA Professional Members whose operations require actively managing avalanche hazards. InfoEx gives avalanche professionals access to data that is accurate, relevant and real time. This knowledge improves each subscriber’s awareness of the conditions, greatly enhancing their ability to manage their local avalanche risks. InfoEx also serves as one of the key sources of data used by Avalanche Canada’s (AC) and other organizations public avalanche forecasters to produce and verify their products. The value of the InfoEx contribution to the AC public avalanche bulletin is estimated at an excess of $2 million annually. The significance of this contribution by avalanche professionals and their employers to public avalanche safety in the mountains of Canada cannot be overstated. InfoEx Subscribers 2018-19 Downhill Ski Resorts KPOW! Fortress Mountain Dezaiko Lodge • Coast/Chilcotin Big White Ski Resort Catskiing Extremely Canadian • Columbia Castle Mountain Great Canadian Heli-Skiing Golden Alpine Holidays • Kootenay Pass Fernie Alpine Resort Gostlin Keefer Lake Lodge Hyland Backcountry Services • Kootenay Region Grouse Mountain Catskiing Ice Creek Lodge • North Cascades District Kicking Horse Mountain Resort Great Northern Snowcat Skiing Kokanee Glacier • Northwest Region Lake Louise Ski Resort Island Lake Lodge Kootenay Backcountry Guides Ningunsaw Marmot Basin K3 Cat Ski Kyle Rast • Northwest Region Terrace Mount Washington Alpine Resort Kingfisher Heliskiing Lake O’Hara Lodge Northwest Avalanche Solutions Norquay Last Frontier Heliskiing Mistaya Lodge Ltd. -

The BG News February 13, 1987

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-13-1987 The BG News February 13, 1987 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 13, 1987" (1987). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4620. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4620 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Spirits and superstitions in Friday Magazine THE BG NEWS Vol. 69 Issue 80 Bowling Green, Ohio Friday, February 13,1987 Death Funding cut ruled for 1987-88 Increase in fees anticipated suicide by Mike Amburgey said. staff reporter Dalton said the proposed bud- get calls for $992 million Man kills wife, The Ohio Board of Regents statewide in educational subsi- has reduced the University's dies for 1987-88, the same friend first instructional subsidy allocation amount funded for this year. A for 1987-88 by $1.9 million, and 4.7 percent increase is called for by Don Lee unless alterations are made in in the academic year 1988-89 Governor Celeste's proposed DALTON SAID given infla- wire editor budget, University students tionary factors, the governor's could face at least a 25 percent budget puts state universities in The manager of the Bowling instructional fee increase, a difficult place. -

Page 1 *;. S',I K.. ,Ir .:;:. .,R#' ,:En. : '"' 'L I'ir --J Il, Lrl . *;.. . ;1: .'L U"L'i " I1 ,Il

M[ *;. ,is' K.. ,Ir . *;.. .:;:. ;1: .,r#' ,:En. : .'l i'ir --j'"' 'l il, lrl U"l'i " i1 ,il wlapwww.gov.bc.calfw WffiffiffiW ffiW ffiffiffiWffiffiWffi EEFORE YOUR HUNT Special Limited Entry Hunts Applications . .25 MajorRegulationChanges2004-2005 ..' ..'.'7 {new} tiI Definrtions .. ' ' '.... '.3 lmportant Notice - to all Mountain Goat Hunters . .26 Federal Firearms Legislation 6 Safety Guidelines for Hunters in Bear Country ,40 HunterEducation .. '...6 Habrtat Conservation Trust Fund 4t BCResidentHunterNumber'.........6 Badger Sightings Notice (new) . .52 OpenSeasons..., ..........'6 Threatened Caribou Listing . .63 WaterfowlerHeritageDays.. ........'6 Wildlife Permits & Commercial Licences {new) . ., . .77 Change of AddressiName Notiflcation (Form) .77 rl Aboriginal Hunting '..' '7 Wildlife (new form) .77 Limited,Entry Hunting . ' ' ' ' ' ' '7 Record of Receipt forTransporting .85 Licences (incl.Bears,Migratory Birds,& Deer) ... ' ' '....8 Muskwa-Kechika Yanagement Area .....86 Non-residentHunters '.. '... '9 ReportaPoacher/Polluter(new) LicenceFees.. '."...10 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT REGIONS DURING YOUR HUNT Region I Vancouverlsland ........27 TI Site&Access Restrictions ... '.......11 Region 2 Lower Ma,nland . .34 NoHuntingorshootingAreas. ......13 Region3 Thompson.... .. ..'42 What is "Wildlife''? ' . .14 Region4 Kootenay . ..........47 lllegalGuiding '......14 Region 5 Cariboo 57 It's Unlawful .t4 Region6 Skeena .........64 Penalties .....t. IA RegionTA omineca..,.. :... : :..,. : :.... .,,,,,..7) .16 RegionTB Peace , ,........78 r$ -

Ski Resorts (Canada)

SKI RESORTS (CANADA) Resource MAP LINK [email protected] ALBERTA • WinSport's Canada Olympic Park (1988 Winter Olympics • Canmore Nordic Centre (1988 Winter Olympics) • Canyon Ski Area - Red Deer • Castle Mountain Resort - Pincher Creek • Drumheller Valley Ski Club • Eastlink Park - Whitecourt, Alberta • Edmonton Ski Club • Fairview Ski Hill - Fairview • Fortress Mountain Resort - Kananaskis Country, Alberta between Calgary and Banff • Hidden Valley Ski Area - near Medicine Hat, located in the Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park in south-eastern Alberta • Innisfail Ski Hill - in Innisfail • Kinosoo Ridge Ski Resort - Cold Lake • Lake Louise Mountain Resort - Lake Louise in Banff National Park • Little Smokey Ski Area - Falher, Alberta • Marmot Basin - Jasper • Misery Mountain, Alberta - Peace River • Mount Norquay ski resort - Banff • Nakiska (1988 Winter Olympics) • Nitehawk Ski Area - Grande Prairie • Pass Powderkeg - Blairmore • Rabbit Hill Snow Resort - Leduc • Silver Summit - Edson • Snow Valley Ski Club - city of Edmonton • Sunridge Ski Area - city of Edmonton • Sunshine Village - Banff • Tawatinaw Valley Ski Club - Tawatinaw, Alberta • Valley Ski Club - Alliance, Alberta • Vista Ridge - in Fort McMurray • Whispering Pines ski resort - Worsley British Columbia Page 1 of 8 SKI RESORTS (CANADA) Resource MAP LINK [email protected] • HELI SKIING OPERATORS: • Bearpaw Heli • Bella Coola Heli Sports[2] • CMH Heli-Skiing & Summer Adventures[3] • Crescent Spur Heli[4] • Eagle Pass Heli[5] • Great Canadian Heliskiing[6] • James Orr Heliski[7] • Kingfisher Heli[8] • Last Frontier Heliskiing[9] • Mica Heliskiing Guides[10] • Mike Wiegele Helicopter Skiing[11] • Northern Escape Heli-skiing[12] • Powder Mountain Whistler • Purcell Heli[13] • RK Heliski[14] • Selkirk Tangiers Heli[15] • Silvertip Lodge Heli[16] • Skeena Heli[17] • Snowwater Heli[18] • Stellar Heliskiing[19] • Tyax Lodge & Heliskiing [20] • Whistler Heli[21] • White Wilderness Heli[22] • Apex Mountain Resort, Penticton • Bear Mountain Ski Hill, Dawson Creek • Big Bam Ski Hill, Fort St. -

Develop a Relationship Map That Discussed What KCP Parners Are

Partner Profiles 2017 Together we’re taking care of our natural landscapes and our Kootenay way of life. The KCP partnership seeks to cooperatively conserve and steward landscapes that sustain naturally functioning ecosystems. We envision vibrant communities that demonstrate the principles of environmental stewardship that can in turn support economic and social well-being. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 BC HYDRO .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 BLUE LAKE FOREST EDUCATION SOCIETY ............................................................................................................... 3 BRITISH COLUMBIA WILDLIFE FEDERATION ........................................................................................................... 4 CANADIAN COLUMBIA RIVER INTER-TRIBAL FISHERIES COMMISSION ................................................................... 5 CANADIAN INTERMOUNTAIN JOINT VENTURE ...................................................................................................... 6 CANAL FLATS WILDERNESS CLUB ........................................................................................................................... 7 CASTLEGAR AND DISTRICT WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION .............................................................................................. -

Amer-Sports-Annual-Report-2008.Pdf

CONTENT Amer Sports in brief and key fi gures . .1 CEO’s review . .8 Strategy . .12 Mission and values. .14 Vision. .15 Financial targets . .16 Global landscape . .18 Business segments Winter and Outdoor . .24 Ball Sports . .34 Fitness . .42 R&D. .46 Award winning products . .48 Sales and channel management . .54 Supply chain and IT . .56 Human resources . .58 Social responsibility . .62 Board of Directors report and fi nancial statements . .68 Corporate governance . .136 Board of Directors . .146 Executive Board . .148 Amer Sports key brands . .152 Information for investors . .212 Contact information . .213 NET SALES, EUR MILLION EBIT, EUR MILLION 1,732 *) 1,793 1,652 1,577 117.1*) 120.2 100.5 92.2**) 1,036 78.9 04 05 06 07 08 04 05 06 07 08 *) Pro forma *) Pro forma **) Before non-recurring items EQUITY RATIO, % GEARING, % 56 121 112 115 105 34 32 31 31 29 04 05 06 07 08 04 05 06 07 08 NET SALES BY NET SALES BY BUSINESS SEGMENT GEOGRAPHICAL SEGMENT 1 Winter and Outdoor 55% 1 EMEA 46% 2 Ball Sports 31% 2 Americas 43% 3 Fitness 14% 3 Asia Pacific 11% 123 123 1 Amer Sports is the world’s leading sports equipment company We offer technically-advanced products that improve the performance of sports participants. Our major brands include Salomon, Wilson, Precor, Atomic, Suunto, Mavic and Arc’teryx. The company’s business is balanced by our broad portfolio of sports and our presence in all major markets. Amer Sports was founded in 1950 in Finland. It has KEY BRANDS: been listed on the NASDAQ OMX Helsinki Ltd since • Salomon – the mountain sports company 1977. -

Economic Contributions of Winter Sports in a Changing Climate

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Earth Systems Research Center Space (EOS) Winter 2-23-2018 Economic Contributions of Winter Sports in a Changing Climate Hagenstad Consulting, Inc. Elizabeth Burakowski USNH, [email protected] Rebecca Hill Colorado State University - Fort Collins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/ersc Part of the Climate Commons, Recreation Business Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Hagenstad, M., E.A. Burakowski, and R. Hill. 2018. Economic Contributions of Winter Sports in a Changing Climate. Protect Our Winters, Boulder, CO, USA. Feb. 23, 2018. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Earth Systems Research Center by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTIONS OF WINTER SPORTS IN A CHANGING CLIMATE FEBRUARY 2018 MARCA HAGENSTAD, M.S. ELIZABETH BURAKOWSKI, M.S., PH.D. REBECCA HILL, M.S., PH.D. PHOTO: JOHN FIELDER PREFACE CLIMATE ECONOMICS AND THE GYRO MAN PROTECT OUR WINTERS BOARD MEMBER AUDEN SCHENDLER One night this December, I walked back to my hotel after the annual Powder Awards in Breckenridge. It was one of the driest and warmest starts to the Colorado ski season in memory. Having missed dinner, and being, well, a skier, I had spent four hours drinking Moscow mules and beer, growing increasingly hungry, but taking energy from the community feeling of the event. -

C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos

C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos 7 ELEVEN 1.eps 7 ELEVEN 2.eps 7UP 1.eps 7UP 2.eps 7UP CHERRY 1.eps 7UP CHERRY 2.eps 7UP DIET 1.eps 7UP DIET 2.eps 7UP DIET CHERR... 7UP DIET CHERR... S & H GREEN STA... SAA.eps SAAB AUTOMOBIL... SAAB AUTOMOBIL... SABENA AIR 1.eps SABENA AIR 2.eps SABENA WORLD ... SABRE BOATS.eps SACHS.eps SAFE PLACE.eps SAFECO.eps SAFEWAY 1.eps SAFEWAY 2.eps SAINSBURYS 1.eps SAINSBURYS 2.eps SAINSBURYS BAN... SAINSBURYS BAN... SAINSBURYS HO... SAINSBURYS HO... SAINSBURYS SAV... Page 1 C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos SAINSBURYS SAV... SAKS 5TH AVENU... SAKS 5TH AVENU... SAKS 5TH AVENU... SALEM.eps SALOMON.eps SALON SELECTIV... SALTON.eps SALVATION ARMY... SAMS CLUB.eps SAMS NET.eps SAMS PUBLISHIN... SAMSONITE.eps SAMSUNG 1.eps SAMSUNG 2.eps SAN DIEGO STAT... SAN DIEGO UNIV ... SAN DIEGO UNIV ... SAN JOSE UNIV 1.... SAN JOSE UNIV 2.... SANDISK 1.eps SANDISK 2.eps SANFORD.eps SANKYO.eps SANSUI.eps SANYO.eps SAP.eps SARA LEE.eps SAS AIR 1.eps SAS AIR 2.eps Page 2 C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos SASKATCHEWAN ... SASSOON.eps SAT MEX.eps SATELLITE DIREC... SATURDAY MATIN... SATURN 1.eps SATURN 2.eps SAUCONY.eps SAUDI AIR.eps SAVIN.eps SAW JAMMER PR... SBC COMMUNICA... SC JOHNSON WA... SCALA 1.eps SCALA 2.eps SCALES.eps SCCA.eps SCHLITZ BEER.eps SCHMIDT BEER.eps SCHWINN CYCLE... SCIFI CHANNEL.eps SCIOTS.eps SCO.eps SCORE INT'L.eps SCOTCH.eps SCOTIABANK 1.eps SCOTIABANK 2.eps SCOTT PAPER.eps SCOTT.eps SCOTTISH RITE 1... -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.