BENGALIS in EAST LONDON Daniele Lamarche AAU Edited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues I — Ii — Iii — Iv the — Unlimited — Edition

THE — UNLIMITED EDITION ISSUES I — II III IV Many thanks to all our contributors This issue of The Unlimited Edition has for their hard work been printed locally by Aldgate Press, with recycled paper by local Published by supplier Paperback We Made That www.wemadethat.co.uk www.aldgatepress.co.uk www.paperback.coop Designed by Andrew Osman & Stephen Osman www.andrewosman.co.uk www.stephenosman.co.uk THE — UNLIMITED — EDITION ISSUE I — SURVEY — AUGUST 2011 2 THE — UNLIMITED — EDITION ISSUE I — SURVEY — AUGUST 2011 THE — UNLIMITED — EDITION ISSUE I — SURVEY — AUGUST 2011 3 is to record and explore the familiar, the transitory nature of the area for the High Street 2012 Historic Buildings Officer and to celebrate and speculate on the present day commuter. for Tower Hamlets Council, also gives possibilities that lie in its future. Expanding outwards from this critical us his personal perspective on some of In our first issue, ‘Survey’, we focus on highway, articles from Ruth Beale and the restoration works that form part the existing nature of the High Street. Clare Cumberlidge reveal the tight mesh of the wider heritage remit of the High Olympic Park Our contributors have been invited from of social, cultural, ethnic and economic Street 2012 initiative. Whitechapel Market a wide range of disciplines: they have fabric that surrounds the High Street in may hold new delights for you once you Holly Lewis, We Made That watched, read, analysed, photographed Aldgate and Wentworth Street. Such have imagined the stallholders as part of and illustrated the High Street to bring to hidden links and ties are further elaborated a life-sized ‘Happy Families’ card game, Stratford Welcome to Issue I of The Unlimited you a collection of articles as varied, by Esme Fieldhouse and Stephen Mackie, as Hattie Haseler has done, or considered Ω Ω Edition. -

Chaucer’S Birth—A Book Went Missing

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. •CHAPTER 1 Vintry Ward, London Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience. — James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man In the early 1340s, in Vintry Ward, London— the time and place of Chaucer’s birth— a book went missing. It wasn’t a very important book. Known as a ‘portifory,’ or breviary, it was a small volume containing a variety of excerpted religious texts, such as psalms and prayers, designed to be carried about easily (as the name demonstrates, it was portable).1 It was worth about 20 shillings, the price of two cows, or almost three months’ pay for a carpenter, or half of the ransom of an archer captured by the French.2 The very presence of this book in the home of a mer- chant opens up a window for us on life in the privileged homes of the richer London wards at this time: their inhabitants valued books, ob- jects of beauty, learning, and devotion, and some recognized that books could be utilized as commodities. The urban mercantile class was flour- ishing, supported and enabled by the development of bureaucracy and of the clerkly classes in the previous century.3 While literacy was high in London, books were also appreciated as things in themselves: it was 1 Sharpe, Calendar of Letter- Books of the City of London: Letter- Book F, fol. -

Queen Mary, University of London Audio Walking Tour Exploring East London

Queen Mary, University of London Audio walking tour exploring east London www.qmul.ac.uk/eastendtour 01 Liverpool Street Station 07 Brick Lane Mosque Exit Liverpool Street Station via Bishopsgate West exit (near WH Go up Wilkes Street. Turn right down Princelet Street. Then turn right Smith). You will come out opposite Bishopsgate Police Station. Press on to Brick Lane. The Mosque is 30m up on the right-hand side. Press play on your device here. Then cross Bishopsgate. Walk to Artillery play on your device. Lane, which is the first turn on the right after the Woodin’s Shade Pub. 08 Altab Ali Park 02 Artillery Passage Follow Brick Lane (right past Mosque) for 250m (at the end Brick Lane Follow Artillery Lane round to the right (approximately 130m). Artillery becomes Osborn Street) to Whitechapel Road. Altab Ali Park on the Passage is at the bottom on the right (Alexander Boyd Tailoring shop is opposite side of Whitechapel Road, between White Church Lane and on the corner). Press play on your device. Adler Street. Press play on your device. 03 Petticoat Lane Market 09 Fulbourne Street Walk up Artillery Passage. Continue to the top of Widegate Street (past At the East London Mosque cross over Whitechapel Road at the traffic the King’s Store Pub). Turn left onto Middlesex Street (opposite the lights, turn right and walk 100m up to the junction of Fulbourne Street Shooting Star Pub). Continue to the junction with Wentworth Street (on (on the left). Press play on your device. the left). Press play on your device. -

The Voyages of South Asian Seamen, C.1900–1960

IRSH 51 (2006), Supplement, pp. 111–141 DOI: 10.1017/S002085900600263X # 2006 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Mobility and Containment: The Voyages of South Asian Seamen, c.1900–1960Ã Ravi Ahuja LASCARS IN A SEGMENTED LABOUR MARKET In the political and economic context of imperialism, the enormous nineteenth-century expansion of shipping within and beyond the Indian Ocean facilitated the development of a new and increasingly transconti- nental regime of labour circulation. The Indian subcontinent, it is well known, emerged as a seemingly inexhaustible source for plantation, railway, and port labour in British colonies across the globe. Moreover, the new and predominantly seaborne ‘‘circulatory regime’’1 itself relied to a considerable extent on the labour power of South Asian workers, on the lascar, as the maritime counterpart of the ‘‘coolie’’ labourer was called. The number of Indian workers on the decks and in the engine rooms and saloons of merchant vessels grew considerably along with the rise of long- distance steam shipping in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. During the interwar years, on average about 50,000 South Asian seamen were employed on British merchant vessels alone and many thousands more by German and other European shipping companies. In this period, lascars made up roughly a quarter of all ratings on British merchant ships – a proportion that remained fairly stable well into the 1960s, despite the end of the colonial regime.2 Ã Research for this article was undertaken during a fellowship at the Centre for Modern Oriental Studies (Berlin) and funded by the German Research Council. I have greatly profited from the lively discussions of the Centre’s Indian Ocean History Group (K. -

FOI 9311 Parks in LB Tower Hamlets and List of Parks by Size Since 1938

FOI 9311 Parks created since 1938 Could you please supply a list of all open spaces created from January 1938 to December 2012. Please supply the area of each new open space when created History of parks and open spaces in Tower Hamlets, and their heritage significance The History of Parks and Open Space in Tower Hamlets The parks and open spaces of Tower Hamlets have come about through a variety of processes. Some public open spaces were the result of deliberate design or policy, while others are the result of historic accident or expedience. There were broadly three periods during which public open space was created in Tower Hamlets. These moves were primarily to benefit people, rather than improve land or rental values. The first was the deliberate creation of Victoria Park in the mid 19 th century, the late 19 th century saw the conversion of churchyards to public gardens and the most recent was in the mid 20 th century after World War 2. Various open spaces are the result of late 18 th and 19 th century urban design, being planned formal gardens set in London Squares. As such they are protected by the London Squares Preservation Act, 1931. These sites include Trinity Square Gardens , Arbour Square , Albert Gardens and the little known Oval in Bethnal Green. See full list of protected London Squares below. Many churchyards, particularly in the west of borough became public open spaces managed by the local authority. Having been closed to further burial use because they were overflowing, they were converted in the second half of the 19 th century into public gardens. -

Broad Street Ward News

December 2016 Broad Street Guildhall School of Music & Drama – A centre of excellence for Performing Arts This is the final article for the Ward Since its founding in 1880, the School has performances by ensembles with which Newsletter this year featuring the stood as a vibrant showcase of the City the Guildhall School is associated, Committees of which the Members of London Corporation’s commitment namely Britten Sinfonia, the Academy of Common Council for the Ward to education and the arts. The School of Ancient Music and the BBC Singers. of Broad Street are Chairmen. The is run by the Principal, Professor Barry Ife Student performances are open to the Ward is probably unique in that all its CBE, supported by three Vice Principals public and tickets are available at very Common Councilmen are Chairmen (Music, Drama and Academic). The reasonable prices. of major committees of the City of School recently announced that Lynne London Corporation. The two previous Williams will become the next Principal, In 2014, following an application Newsletters have featured the submitted to the Higher Education Markets Committee chaired by John Funding Council for England (HEFCE), Scott CC and the Planning and the School was granted first degree Transportation Committee chaired awarding powers, enabling it to confer by Chris Hayward CC. its own first degrees rather than those of City University. John Bennett, Deputy for the Ward, is Chairman of the Board of Governors This summer, HEFCE conducted an of the Guildhall School of Music & institution-specific review which resulted Drama, owned by the City Corporation in the Guildhall School’s teaching being and part of the City’s Cultural Hub. -

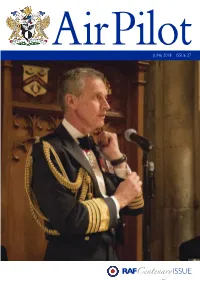

Airpilotjune 2018 ISSUE 27

2 AirPilot JUNE 2018 ISSUE 27 RAF ISSUE Centenar y Diary JUNE 2018 AI R PILOT 14th General Purposes & Finance Committee Cutlers’ Hall 25th Election of Sheriffs Guildhall THE HONOURABLE 28th T&A Committee Dowgate Hill House COMPANY OF AIR PILOTS incorporating Air Navigators JULY 2018 12th Benevolent Fund Dowgate Hill House PATRON : 12th ACEC Dowgate Hill House His Royal Highness 16th Summer Supper Watermen’s Hall The Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh KG KT 16th Instructors’ Working Group Dowgate Hill House 19th General Purposes & Finance Committee Dowgate Hill House GRAND MASTER : 19th Court Cutlers’ Hall His Royal Highness The Prince Andrew Duke of York KG GCVO MASTER : VISITS PROGRAMME Captain Colin Cox FRAeS Please see the flyers accompanying this issue of Air Pilot or contact Liveryman David Curgenven at [email protected]. CLERK : These flyers can also be downloaded from the Company's website. Paul J Tacon BA FCIS Please check on the Company website for visits that are to be confirmed. Incorporated by Royal Charter. A Livery Company of the City of London. PUBLISHED BY : GOLF CLUB EVENTS The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, Please check on Company website for latest information Dowgate Hill House, 14-16 Dowgate Hill, London EC4R 2SU. EDITOR : Paul Smiddy BA (Econ), FCA EMAIL: [email protected] FUNCTION PHOTOGRAPHY : Gerald Sharp Photography View images and order prints on-line. TELEPHONE: 020 8599 5070 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.sharpphoto.co.uk PRINTED BY: Printed Solutions Ltd 01494 478870 Except where specifically stated, none of the material in this issue is to be taken as expressing the opinion of the Court of the Company. -

Green Flag Award Winners 2019 England East Midlands 125 Green Flag Award Winners

Green Flag Award Winners 2019 England East Midlands 125 Green Flag Award winners Park Title Heritage Managing Organisation Belper Cemetery Amber Valley Borough Council Belper Parks Amber Valley Borough Council Belper River Gardens Amber Valley Borough Council Crays Hill Recreation Ground Amber Valley Borough Council Crossley Park Amber Valley Borough Council Heanor Memorial Park Amber Valley Borough Council Pennytown Ponds Local Nature Reserve Amber Valley Borough Council Riddings Park Amber Valley Borough Council Ampthill Great Park Ampthill Town Council Rutland Water Anglian Water Services Ltd Brierley Forest Park Ashfield District Council Kingsway Park Ashfield District Council Lawn Pleasure Grounds Ashfield District Council Portland Park Ashfield District Council Selston Golf Course Ashfield District Council Titchfield Park Hucknall Ashfield District Council Kings Park Bassetlaw District Council The Canch (Memorial Gardens) Bassetlaw District Council A Place To Grow Blaby District Council Glen Parva and Glen Hills Local Nature Reserves Blaby District Council Bramcote Hills Park Broxtowe Borough Council Colliers Wood Broxtowe Borough Council Chesterfield Canal (Kiveton Park to West Stockwith) Canal & River Trust Erewash Canal Canal & River Trust Queen’s Park Charnwood Borough Council Chesterfield Crematorium Chesterfield Borough Council Eastwood Park Chesterfield Borough Council Holmebrook Valley Park Chesterfield Borough Council Poolsbrook Country Park Chesterfield Borough Council Queen’s Park Chesterfield Borough Council Boultham -

By SIR ALEXANDER GRAHAM, GBE

1979 to 2004 - by SIR ALEXANDER GRAHAM, GBE I was elected unopposed as Alderman of the Ward in 1979, succeeding Peter Theobald who sadly had to retire from ill health. I had been elected a Common Councilman for the Ward of Cheap in 1978 and stood for Queenhithe with the encouragement of several Aldermen including Sir Christopher Leaver and Sir Hugh Wontner. I was the first member of the Mercers Livery Company to become an Alderman for over two hundred years and the first Mercer to become Alderman of Queenhithe for over three hundred years. Almost the first thing that happened following my election was that the ward church St Nicholas Cole Abbey was declared redundant by the Church of England and the lease was taken up by the Free Church of Scotland (the Wee Frees). An inaugural service was held attended by former Rectors including one who had become a bishop. The service took me back to my childhood in Scotland where in the Free Church you stand up to pray and sit down to sing with out an organ. Like the Jewish faith they have a Presenter (Cantor) who starts the singing. On occasions when my mother was away from our village in Scotland I stayed with the Headmaster of the village school and went to similar services with very long sermons. The Free Church turned out to be very nice and the Minister of the time the Rev’d John Nicholls was my Chaplain when I was both Sheriff and Lord Mayor. At this time Queenhithe was the centre of the world fur trade with 83% of the world’s fur being traded through the ward, sadly this has all disappeared. -

2018 Autumn Update – Ward of Cheap Team Working for the City

Our pledges to you ü Improving air quality ü Tackling congestion and road safety for all users ü Promoting diversity and social mobility ü Supporting a vibrant Cheapside business community 2018 Autumn update – Ward of ü Ensuring a safe City, addressing begging and ending rough sleeping Cheap Team working for the City ü Protecting and promoting the City through Brexit Welcome to our Autumn Report updang you on the work as your ü Stewarding the City Corporation’s investment and charity projects local representaves over the last few months. Our first report aer the elec1on CONTACT US INCREASED SUPPORT FOR CITY TRANSPORT STRATEGY of our new Alderman Robert EDUCATION Hughes-Penney. A huge thank As your local representaves We would like to hear from you you to everyone who came out we are here to help and make The City Corporaon and Livery what you think about the City’s to vote in July. Turn out was sure your voice is heard. Companies have historically dra strategy, which will shape strong with 54.9%. Throughout the year we will always been great supporters the City for the next 25 years. keep you informed of our work, of educaon. Today this The plan aims to deliver world- In this report we feedback on key but do feel free to contact us supports con1nues - recently class connec1ons and a SQuare issues we have taken the lead on any1me. strengthened with new City Mile that is accessible to all as a team over the last few skills, appren1ceships and including: months. Your Ward Team (le. -

THE-RELAY-BUILDING-SCREEN-BROCHURE-June-2015.Pdf

CONTEMPORARY OFFICE SPACE SPECIFICALLY DESIGNED TO MEET THE ASPIRATIONS OF MODERN OCCUPIERS The Relay Building has been designed as a class architectural design. Styled for modern catalyst for attracting a new generation businesses with a progressive outlook, The of occupier to Aldgate East, London’s most Relay Building aims to bring together a upcoming and thriving district and one of dynamic community of like-minded tenants the best connected transport hubs in London. who are adopting new attitudes towards It provides sociable and flexible warehouse mutual workstyles, sharing ideas and making inspired space and delivers six large floors connections. of outstanding open plan offices with top THE BUILDING IS LOCATED IN THE HEART OF ALDGATE, THE NEW DESTINATION FOR FORWARD THINKING AND CREATIVE BUSINESSES Shoreditch High St. (9 mins) Shoreditch Spitalfields Whitechapel (9 mins) Liverpool St. (8 mins) Whitechapel Aldgate Aldgate East (1 min) Aldgate (2 mins) The City Fenchurch St. (6 mins) Tower Hill (8 mins) N Box Park 19 18 Shoreditch House Local Amenities 01 Wagamama 14 Misschu 02 Sushi Samba 15 Whitechapel Gallery Commercial St. 03 Aldgate Coffee House 16 Fitness First 04 Marco Pierre White’s 17 LA Fitness Steak & Alehouse 18 Box Park 05 Duck & Waffle 19 Shoreditch House 22 06 Bodean’s 20 The Diner 07 Jamie’s Wine Bar & Restaurant 21 The Culpeper 21 20 01 08 The Sterling 22 The Big Chill 09 Trade Coffee 23 The Ten Bells Spitalfields Market 10 Barcelona Tapas 24 Andaz Hotel 23 Andaz Hotel 11 Mumbai Square 12 Exmouth Coffee Company 24 13 Zengi 20 Commer Whitechapel High St. -

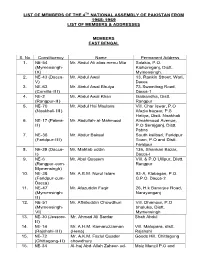

List of Members of the 4Th National Assembly of Pakistan from 1965- 1969 List of Members & Addresses

LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE 4TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN FROM 1965- 1969 LIST OF MEMBERS & ADDRESSES MEMBERS EAST BENGAL S. No Constituency Name Permanent Address 1. NE-54 Mr. Abdul Ali alias menu Mia Solakia, P.O. (Mymensingh- Kishoreganj, Distt. IX) Mymensingh. 2. NE-43 (Dacca- Mr. Abdul Awal 13, Rankin Street, Wari, V) Dacca 3. NE-63 Mr. Abdul Awal Bhuiya 73-Swamibag Road, (Comilla-III) Dacca-1 4. NE-2 Mr. Abdul Awal Khan Gaibandha, Distt. (Rangpur-II) Rangpur 5. NE-70 Mr. Abdul Hai Maulana Vill. Char Iswar, P.O (Noakhali-III) Afazia bazaar, P.S Hatiya, Distt. Noakhali 6. NE-17 (Pabna- Mr. Abdullah-al-Mahmood Almahmood Avenue, II) P.O Serajganj, Distt. Pabna 7. NE-36 Mr. Abdur Bakaul South kalibari, Faridpur (Faridpur-III) Town, P.O and Distt. Faridpur 8. NE-39 (Dacca- Mr. Mahtab uddin 136, Shankari Bazar, I) Dacca-I 9. NE-6 Mr. Abul Quasem Vill. & P.O Ullipur, Distt. (Rangpur-cum- Rangpur Mymensingh) 10. NE-38 Mr. A.B.M. Nurul Islam 93-A, Klabagan, P.O. (Faridpur-cum- G.P.O. Dacca-2 Dacca) 11. NE-47 Mr. Afazuddin Faqir 26, H.k Banerjee Road, (Mymensingh- Narayanganj II) 12. NE-51 Mr. Aftabuddin Chowdhuri Vill. Dhamsur, P.O (Mymensingh- bhaluka, Distt. VI) Mymensingh 13. NE-30 (Jessore- Mr. Ahmad Ali Sardar Shah Abdul II) 14. NE-14 Mr. A.H.M. Kamaruzzaman Vill. Malopara, distt. (Rajshahi-III) (Hena) Rajshahi 15. NE-72 Mr. A.K.M. Fazlul Quader Goods Hill, Chittagong (Chittagong-II) chowdhury 16. NE-34 Al-haj Abd-Allah Zaheer-ud- Moiz Manzil P.O and (Faridpur-I) Deen (Lal Mian).