2008 Mumbai Terrorist Attacks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

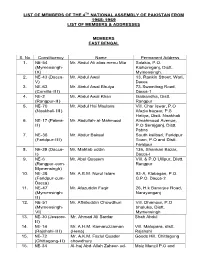

List of Members of the 4Th National Assembly of Pakistan from 1965- 1969 List of Members & Addresses

LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE 4TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN FROM 1965- 1969 LIST OF MEMBERS & ADDRESSES MEMBERS EAST BENGAL S. No Constituency Name Permanent Address 1. NE-54 Mr. Abdul Ali alias menu Mia Solakia, P.O. (Mymensingh- Kishoreganj, Distt. IX) Mymensingh. 2. NE-43 (Dacca- Mr. Abdul Awal 13, Rankin Street, Wari, V) Dacca 3. NE-63 Mr. Abdul Awal Bhuiya 73-Swamibag Road, (Comilla-III) Dacca-1 4. NE-2 Mr. Abdul Awal Khan Gaibandha, Distt. (Rangpur-II) Rangpur 5. NE-70 Mr. Abdul Hai Maulana Vill. Char Iswar, P.O (Noakhali-III) Afazia bazaar, P.S Hatiya, Distt. Noakhali 6. NE-17 (Pabna- Mr. Abdullah-al-Mahmood Almahmood Avenue, II) P.O Serajganj, Distt. Pabna 7. NE-36 Mr. Abdur Bakaul South kalibari, Faridpur (Faridpur-III) Town, P.O and Distt. Faridpur 8. NE-39 (Dacca- Mr. Mahtab uddin 136, Shankari Bazar, I) Dacca-I 9. NE-6 Mr. Abul Quasem Vill. & P.O Ullipur, Distt. (Rangpur-cum- Rangpur Mymensingh) 10. NE-38 Mr. A.B.M. Nurul Islam 93-A, Klabagan, P.O. (Faridpur-cum- G.P.O. Dacca-2 Dacca) 11. NE-47 Mr. Afazuddin Faqir 26, H.k Banerjee Road, (Mymensingh- Narayanganj II) 12. NE-51 Mr. Aftabuddin Chowdhuri Vill. Dhamsur, P.O (Mymensingh- bhaluka, Distt. VI) Mymensingh 13. NE-30 (Jessore- Mr. Ahmad Ali Sardar Shah Abdul II) 14. NE-14 Mr. A.H.M. Kamaruzzaman Vill. Malopara, distt. (Rajshahi-III) (Hena) Rajshahi 15. NE-72 Mr. A.K.M. Fazlul Quader Goods Hill, Chittagong (Chittagong-II) chowdhury 16. NE-34 Al-haj Abd-Allah Zaheer-ud- Moiz Manzil P.O and (Faridpur-I) Deen (Lal Mian). -

S. No. Folio No. Security Holder Name Father's/Husband's Name Address

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders without / invalid CNIC # as of 31-12-2019 S. Folio No. Security Holder Name Father's/Husband's Name Address No. of No. Securities 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN S/O MR. MOHAMMAD WAZIR KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI S/O MR. MOHD ABDUL HAFEEZ 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3,280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN S/O MURTUZA MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD MR. HAMID HUSSAIN C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE S/O A. RAHIM B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9,382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED S/O GHULAM QADDIR KHAN H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN S/O MOHD NASRULLAH KHAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA S/O FAZAL-I-MAHMOOD 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1,919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN S/O ABDUR REHMAN KHAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8,530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN SARDAR M. FAROOQ IBRAHIM 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5,945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN S/O KH. -

Abbas Tayabji, 27. Abbotabad, 145, 194, 195. Abdul Aziz, 42, 43, 48

Index A Abbas Tayabji, 27. Abdul Rahim, Moulvi, Calcutta, 230. Abbotabad, 145, 194, 195. Abdul Rahim, Syed 249, 333. Abdul Aziz, 42, 43, 48, 248, Abdul Rahman, 248. 331, 334. Abdul Rauf, Syed, Barrister, Abdul Aziz, Barrister, Allahabad, 231. Peshawar, 232. Abdul Salam, Molvi, Sylhet, Assam, Abdul Aziz, Editor Observer , 129. Lahore, 232. Abdul Sattar, Haji, 172. Abdul Aziz, Syed, 74, 75, 77. Abdullah-al-Mahmood, 186. Abdul Hamid, Molvi, Sylhet, Abdullah Haroon, Sir, 62, 67, 68, 70, Assam, 129. 72, 78, 83, 85. Abdul Hashim, 187. Abdullah, Sheikh, 30, 232. Abdul Haye, Mian, 81. Abdullah, Sheikh Muhammad, 40, 45. Abdul Hye, Molvi, Habibgang, Abdur Rahim, Sir, 30, 85. Assam, 130. Abdur Rahman, Molvi, 129. Abdul Jabbar (Ajmere), 249. Abdur Rauf, Hakim Maulana, 26. Abdul Karim, Moulvi, 36, 44. Abdur Rauf, Molvi, Syed, M.L.A. Abdul Kasem, Moulvi, 43. Barpeta, Assam, 72, 130. Abdul Latif, Syed, 78. Abdussalam Khan, Retired Abdul Majeed, Editor, Muslim Sub.Judge, Rampur, 231. Chronicle , Calcutta, 231. Abdus Samad, Maulvi, 65, 129. Abdul Majid, 6. Adamjee, Ibrahim Bhoy, Sir, Peer Abdul Majid, Moulvi, Barrister, Bhoy, Bombay, 200, 227, 230. Allahabad, 232. Afghan Jirga, 155. Abdul Majid, Moulvi, Sylhet, Afridi, 178. 231. Aga Khan, H.H. Sir Sultan Abdul Majid, Sh., 51, 62, 70. Mohammad Shah, 2, 7-9, 40, 44, Abdul Matin, Chaudhry, 48. 229, 331. Abdul Qadir, Mirza, 249, 333. Agra, 13, 226, 233, 332. Abdul Qadir, Shaikh Ahmad Khan, 182. Mohammad, 31, 233. Ahmad, Molvi Kajimuddin, Barpita, Abdul Qaiyum, Sir, 50, 248. Dt. Darang, Assam, 130. 340 All India Muslim League Ahmad, Moulvi Rafiuddin, Allana, Mrs., 182. -

A Chronology

A CHRONOLOGY 1906 30 Dec. The concluding day of the 20 th session of the All-India Mohammedan Educational Conference (AIMEC) in Dacca. After the Session was over, the delegates reassembled in the pandal to discuss the formation of a political organization of Muslims. On Nawab Salimullah Bahadur of Dacca’s proposal Nawab Viqarul-Mulk, Maulvi Mushtaq Hussain Bahadur, was elected chairman, and on Nawab Salimullah’s proposal, again, it was decided to form a political organization, called the All India Muslim League (AIML), with the following aims and objects: i). To promote among the Musalmans of India feelings of loyalty to the British Government and to remove any misconception that may arise as to the intention of government with regard to any of its measures; ii). To protect and advance the political rights and interests of the Musalmans of India and to respectfully represent their needs and aspirations; and iii). To protect among the Musalmans of India of any feeling of hostility towards other communities without prejudice to the other aforementioned objects of the League. A Provisional Committee was formed with Nawab Viqarul Mulk and Nawab Mohsinul Mulk as Joint Secretaries, to frame the Constitution of the AIML within four months. 2 All India Muslim League 1907 29-30 Dec . First session of the AIML held at Karachi, with Sir Adamjee Peerbhoy as President. It resolved that Rules and Regulations of the AIML be framed as early as possible. Two Provincial Branches in the Punjab, one established in Feb. 1906 and the other in Dec. 1906, were merged together with Mian (later Justice) Shah Din as President, Mian Muhammad Shafi as General Secretary and Mian Fazl-i-Hussain as Joint Secretary. -

Behind the Myth of Three Million

BEHIND THE MYTH OF THREE MILLION By Dr. M. Abdul Mu’min Chowdhury Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar ABOUT THE AUTHOR The author, Dr. M. Abdul Mu’min Chowdhury, a native of Sylhet, was educated at the universities of Dhaka, Exeter (England) and London. As a teacher of Sociology, he taught in his early career at the universities of Agriculture (East Pakistan) and Dhaka during the period of 1967 to 1973. Apart from his working association with Dr. Hasan Zaman at the Bureau of National Reconstruction (BNR), Dhaka, in late 1960s for undertaking many research works, he continued to write for many newspapers and also edited a few published from Dhaka and London. He co-authored some periodicals and books including the Iron Bars of Freedom (1981) published from London during the period from mid 1970s and early 1980s with the late Dr. Matiur Rahman who himself authored a number of books on the political history of the Indian subcontinent until his demise in London In 1982. Since late 1973, Dr. Chowdhury lives in England and works currently as a Management Consultant. CONTENTS 1 Preface .. .. .. .. .. 1 2 Chapter One The Making of the Myth .. .. .. .. 4 3 Chapter Two The Probity of the Myth .. .. .. .. 11 4 Chapter Three Mujib’s Search for Fact .. .. .. .. 18 5 Chapter Four The Truth that Mujib Suppressed .. .. 22 6 Chapter Five The Recycling of the Myth .. .. .. .. 25 7 Chapter Six The Forgotten Humanity .. .. .. .. 38 8 Chapter Seven The Glimpses of Truth .. .. .. .. 45 9 Chapter Eight Behind the Myth .. .. .. .. .. 48 PREFACE Many myths have been formed around the creation of Bangladesh. -

BENGALIS in EAST LONDON Daniele Lamarche AAU Edited

BENGALIS IN EAST LONDON: A Community in the Making for 500 Years In The Beginning… Today, some 53,000 of the UK’s 200,000-300,000 Bengalis live in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, and the Brick Lane area lies in the heart of this community. It all began with spices. At a time when pepper was dearer than gold, saffron more rare than diamonds… 1 Sea links and overland routes established in Roman times to India and China fed a growing European appetite for spices. Condiments such as pepper livened up winter foods stored in brine. Cloves offered relief for toothache or, in times of inadequate sanitation, masked body odours. Aromatic woods such as cinnamon were used for perfumes, medicines and flavourings. And textiles such as silks were imported from as far as China and Japan. Such was the importance of the trade that when Constantinople fell to the Muslim Turks in 1453, new trading interfaces were provided. While trade was dominated by Venice, countries such as Portugal and Spain began to explore sea routes with the force of guns and a passionate Christian zeal. The Portuguese established trading points in Malacca, Goa and Macao, the latter port being set up under the tolerance of a Chinese state which itself had trading posts as far off as Kenya. But by 1580, Portuguese and Spanish control of the seas was waning. Protestant Holland and Britain enterer the trade race. Following in the footsteps of explorers such as Francis Drake, early traders in the East Indies raised finances and negotiated a charter with Queen Elisabeth I to create London’s Company of Merchants, on the 31 st of December 1599. -

Annual Report 2011-2012

ASSAM UNIVERSITY 19th ANNUAL REPORT (2011-12) Report on the working of the University (1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012) Dargakona Assam University Silchar – 788011 www.aus.ac.in Compiled and Edited by : Prof. Niranjan Roy, Director Dr. Anindya Syam Choudhury, Asstt. Director Directorate of Internal Quality Assurance (DIQA) i Visitor : Mrs. Pratibha Devisingh Patil Her Excellency, The President of India Chief Rector : Shri Janaki Bhallav Patnaik His Excellency, The Governor of Assam Chancellor : Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, FRS Eminent Scientist and Chairman, NCAFNSI Vice-Chancellor : Prof. Tapodhir Bhattacharjee (Handed over charge to Prof. Somnath Dasgupta on 25-06-2012) Deans of Schools: Prof. Swapna Devi : Rabindranath Tagore School of Indian Languages and Cultural Studies Prof. Gopalji Mishra : Jadunath Sarkar School of Social Sciences Prof. Gautam Biswas : Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan School of Philosophical Studies Prof. G.P. Pandey : Abanindranath Tagore School of Creative Arts and Communication Studies Prof. D.K.Pandiya : Mahatma Gandhi School of Economics and Commerce Prof. D. Biswas : Albert Einstein School of Physical Sciences Prof. G.D. Sharma : Hargobind Khurana School of Life Sciences Prof. B.K. Dutta : E. P Odam School of Environmental Sciences Prof. R.K.Paul : Triguna Sen School of Technology Prof. N.B. Biswas : Ashutosh Mukhopadhyay School of Education Prof. A.M.Bhuiya : Suniti Kumar Chattopadhyay School of English and Foreign Language Studies Prof. R.K.Raul : Jawarharlal Nehru School of Management Prof. Sanjib Das : Susruta School of Medical and Paramedical Sciences Prof. N.Pandey : Aryabhatta School of Earth Sciences Prof. Sajal Nag : Swami Vivekananda School of Library Sciences Prof. R.R.Dhamala : Deshabandhu Chittaranjan School of Legal Studies Registrar : Sri Debabrata Deb (up to 31-12-2011) : Prof.Niranjan Roy (since 01-01-12) Finance Officer : Mr. -

The 2008 Mumbai Terrorist Attacks

The 2008 Mumbai Terrorist Attacks Strategic Fallout RSIS Monograph No. 17 Rajesh Basrur Timothy Hoyt Rifaat Hussain Sujoyini Mandal RSIS MONOGRAPH NO. 17 THE 2008 MUMBAI TERRORIST AttACKS STRATEGIC FALLOUT Rajesh Basrur Timothy Hoyt Rifaat Hussain Sujoyini Mandal S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies i Copyright © 2009 Rajesh Basrur, Timothy Hoyt, Rifaat Hussain and Sujoyini Mandal Published by S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University South Spine, S4, Level B4, Nanyang Avenue Singapore 639798 Telephone: 6790 6982 Fax: 6793 2991 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.idss.edu.sg First published in 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. Body text set in 11/14 point Warnock Pro Produced by BOOKSMITH ([email protected]) ISBN 978-981-08-4684-8 ii The RSIS/IDSS Monograph Series Monograph No. Title 1 Neither Friend Nor Foe Myanmar’s Relations with Thailand since 1988 2 China’s Strategic Engagement with the New ASEAN 3 Beyond Vulnerability? Water in Singapore-Malaysia Relations 4 A New Agenda for the ASEAN Regional Forum 5 The South China Sea Dispute in Philippine Foreign Policy Problems, Challenges and Prospects 6 The OSCE and Co-operative Security in Europe Lessons for Asia 7 Betwixt and Between Southeast Asian Strategic Relations with