ANN BANFIELD • the “Rip Word” and Tattered Syntax: from “The Word Go” to “The Word Begone”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Is Endlessness Somewhere Else

Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau White Office 26, rue George Sand, 37000 Tours Vernissage : vendredi 21 mai 2010 Exposition du 22 mai au 13 juin 2010 Titre : Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else (Bas Jan Ader (“here is always somewhere else”) + Samuel Beckett (“lessness” – “sans”)) James Joyce, “Ulysse” : “le froid des espaces interstellaires, des milliers de degrés en-dessous du point de congélation ou du zéro absolu de Fahrenheit, centigrade ou Réaumur : les indices premiers de l’aube proche.” Alphaville – Jean-Luc Godard Alfaville Mel Bochner & TTrioreau (4 affiches perforées sur mur gris – édition multiples : 5 + 2 EA) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (néon blanc sur mur gris – édition multiples : 5 + 2 EA) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – façade grise + fenêtre écran, format panavision 2/35) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – intérieur gris + projecteur 35mm, film 35mm vierge gris, format panavision 2/35 + néon blanc sur mur gris) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – intérieur gris + projecteur 35mm, film 35mm vierge gris, format panavision 2/35 + néon blanc sur mur gris) Annexes : Lessness A Story by SAMUEL BECKETT (1970) Ruins true refuge long last towards which so many false time out of mind. All sides endlessness earth sky as one no sound no stir. Grey face two pale blue little body heart beating only up right. Blacked out fallen open four walls over backwards true refuge issueless. Scattered ruins same grey as the sand ash grey true refuge. Four square all light sheer white blank planes all gone from mind. Never was but grey air timeless no sound figment the passing light. -

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works Theresa A. Incampo Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Incampo, Theresa A., "The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/209 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical and Sonic Landscapes within the Short Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett Submitted by Theresa A. Incampo May 4, 2012 Trinity College Department of Theater and Dance Hartford, CT 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 5 I: History Time, Space and Sound in Beckett’s short dramatic works 7 A historical analysis of the playwright’s theatrical spaces including the concept of temporality, which is central to the subsequent elements within the physical, metaphysical and sonic landscapes. These landscapes are constructed from physical space, object, light, and sound, so as to create a finite representation of an expansive, infinite world as it is perceived by Beckett’s characters.. II: Theory Phenomenology and the conscious experience of existence 59 The choice to focus on the philosophy of phenomenology centers on the notion that these short dramatic works present the theatrical landscape as the conscious character perceives it to be. The perceptual experience is explained by Maurice Merleau-Ponty as the relationship between the body and the world and the way as to which the self-limited interior space of the mind interacts with the limitless exterior space that surrounds it. -

Naadac Wellness and Recovery in the Addiction

NAADAC WELLNESS AND RECOVERY IN THE ADDICTION PROFESSION 2:00 PM - 3:30 PM CENTRAL MAY 5, 2021 CAPTIONING PROVIDED BY: CAPTIONACCESS [email protected] www.captionaccess.com >> HeLLo, everyone and weLcome to part 5 of 6 of the speciaLty onLine training series on weLLness and recovery. Today's topic is MindfuLness with CLients - Sitting with Discomfort presented by Cary Hopkins Eyles. I'm reaLLy excited to have you guys as part of this presentation. My name is Jessie O'Brien. I'm the training and content manager here at NAADAC the association for addiction professionaLs. And I wiLL be the organizer for today's Learning experience. This onLine training is produced by NAADAC, the association for addiction professionaLs. CLosed captioning is provided by CaptionAccess today. So pLease check your most recent confirmation emaiL for a key Link to use closed captioning. As many of you know, every NAADAC onLine speciaLty series has its own webpage that houses everything you need to know about that particuLar series. If you missed a part of the series and decide to pursue the certificate of achievement you can register for the training that you missed, ticket on demand at your own pace, make the payment and take the quiz. You must be registered for any NAADAC training in order to access the quiz and get the credit. If you want any more information on the weLLness and recovery series, you can find it right there at that page. So this training today is approved for 1.5 continuing education hours, and our website contains a fuLL List of the boards and organizations that approve us as continuing education providers. -

Beckett and Nothing with the Negative Spaces of Beckett’S Theatre

8 Beckett, Feldman, Salcedo . Neither Derval Tubridy Writing to Thomas MacGreevy in 1936, Beckett describes his novel Murphy in terms of negation and estrangement: I suddenly see that Murphy is break down [sic] between his ubi nihil vales ibi nihil velis (positive) & Malraux’s Il est diffi cile à celui qui vit hors du monde de ne pas rechercher les siens (negation).1 Positioning his writing between the seventeenth-century occasion- alist philosophy of Arnold Geulincx, and the twentieth-century existential writing of André Malraux, Beckett gives us two visions of nothing from which to proceed. The fi rst, from Geulincx’s Ethica (1675), argues that ‘where you are worth nothing, may you also wish for nothing’,2 proposing an approach to life that balances value and desire in an ethics of negation based on what Anthony Uhlmann aptly describes as the cogito nescio.3 The second, from Malraux’s novel La Condition humaine (1933), contends that ‘it is diffi cult for one who lives isolated from the everyday world not to seek others like himself’.4 This chapter situates its enquiry between these poles of nega- tion, exploring the interstices between both by way of neither. Drawing together prose, music and sculpture, I investigate the role of nothing through three works called neither and Neither: Beckett’s short text (1976), Morton Feldman’s opera (1977), and Doris Salcedo’s sculptural installation (2004).5 The Columbian artist Doris Salcedo’s work explores the politics of absence, par- ticularly in works such as Unland: Irreversible Witness (1995–98), which acts as a sculptural witness to the disappeared victims of war. -

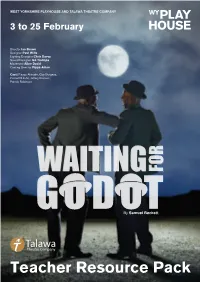

Waiting for Godot’

WEST YORKSHIRE PLAYHOUSE AND TALAWA THEATRE COMPANY 3 to 25 February Director Ian Brown Designer Paul Wills Lighting Designer Chris Davey Sound Designer Ian Trollope Movement Aline David Casting Director Pippa Ailion Cast: Fisayo Akinade, Guy Burgess, Cornell S John, Jeffery Kissoon, Patrick Robinson By Samuel Beckett Teacher Resource Pack Introduction Hello and welcome to the West Yorkshire Playhouse and Talawa Theatre Company’s Educational Resource Pack for their joint Production of ‘Waiting for Godot’. ‘Waiting for Godot’ is a funny and poetic masterpiece, described as one of the most significant English language plays of the 20th century. The play gently and intelligently speaks about hardship, friendship and what it is to be human and in this unique Production we see for the first time in the UK, a Production that features an all Black cast. We do hope you enjoy the contents of this Educational Resource Pack and that you discover lots of interesting and new information you can pass on to your students and indeed other Colleagues. Contents: Information about WYP and Talawa Theatre Company Cast and Crew List Samuel Beckett—Life and Works Theatre of the Absurd Characters in Waiting for Godot Waiting for Godot—What happens? Main Themes Extra Activities Why Godot? why now? Why us? Pat Cumper explains why a co-production of an all-Black ‘Waiting for Godot’ is right for Talawa and WYP at this time. Interview with Ian Brown, Director of Waiting for Godot In the Rehearsal Room with Assistant Director, Emily Kempson Rehearsal Blogs with Pat Cumper and Fisayo Akinade More ideas for the classroom to explore ‘Waiting For Godot’ West Yorkshire Playhouse / Waiting for Godot / Resource Pack Page 1 Company Information West Yorkshire Playhouse Since opening in March 1990, West Yorkshire Playhouse has established a reputation both nationally and internationally as one of Britain’s most exciting producing theatres, winning awards for everything from its productions to its customer service. -

6 X 10 Long.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86520-3 - Samuel Beckett and the Philosophical Image Anthony Uhlmann Index More information Index Abbott, H. Porter 106 Bre´hier, Emile 130, 134–6, 143, 145, 153 Ackerley, C. J. 39, 70 ...but the clouds ...2, 62 All That Fall 63 All Strange Away 2, 49, 64, 104 ‘Calmative, The’ 50, 61 Aldington, Richard 30 Carroll, Lewis 134 Altman, Robert 16, 17 Catastrophe 122, 129 Anzieu, Didier 112 Chaikin, Joseph 51 A Piece of Monologue 62 Chrysippus 130, 133, 141 Aristotle 71 Cioran, Emil 129 Arrabal, Fernando 129 Cicero 131 ‘As the Story Was Told’ 49 Cleanthes 130, 133 Cle´ment, Bruno 108–9, 110, 112 Bacon, Sir Francis 67, 92 cliche´ 12–14, 16–17 Badiou, Alain 112 ‘Cliff, The’ 50 Bakhtin, Mikhail 2, 57, 75 Cohn, Ruby 1, 48 Bataille, Georges 108 Come and Go 45, 62, 138, 139, 140 Beckett, Samuel Company 50 on Jack Yeats 24, 30–1 Conrad, Joseph 124 letter to Georges Duthuit 1949 26, 37–8, 117 Czerny, Carl 1 and knowledge of Bergson 29–31, 117–18 and letter to Axel Kaun 54, 66 d’Aubare`de, Gabriel 72, 74 on Joyce 56 Dante Alighieri 78, 104 and the nature of the image in his works ‘Dante ...Bruno. Vico.. Joyce’ 26, 74 62–4 Dearlove, J. E. 36 reading of Geulincx’ Ethics 70, 81, 90–105 Defoe, Daniel 68 and the image of the rocking chair 78–85 de Lattre, Alain 69 and images adapted from Geulincx 90–105 Deleuze, Gilles 2, 112, 147–8 and his notes to his reading of Geulincx 90–1, and minor tradition 5 92, 131 and Cinema books 6–14, 18–21 and the image of the voice 94–5 and the image in Beckett 31–5 Beethoven, Ludwig van -

Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World, Let Us Listen to Their Echoes and Take Note of the Indica Tions These May Afford

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com ^arbaro (College ILtbrarg FROM THE GEORGE B. SOHIER PRIZE FUND "The surplus each year over and above what shall be required for the prize shall be expended for books for the library ' ' c FOOTFALLS ON THE Boundary of Another World. WITH NARRATIVE ILLUSTRATIONS. BY ROBERT DALE OWEN", FORMERLY MEMBER OF CONGRESS, AND AMERICAN MINISTER TO NAPLES. " As it is the peculiar method of the Academy to interpose no personal judgment, 1 mt. to admit those opinions which appear must probable, to compare arguments, and to set forth all that may be reasonably stated in favor of each proposition, and so, without obtruding any authority of its own. to leave the judgment of the hearers free and unprejudiced, we will retain this custom which has l>ecn handed down from Focrates ; and this method, dear brother Quintus, if you please, w - will adopt, as often as possible, in all our dialogues together." — Cicero ds. Divin. Lib, ii. §72. PHILADELPHIA: J. B LIPPINGOTT & CO. 18G5. * Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1859, by J. B. UPPIXCOTT & CO. in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Bantarr District of Penttsylvania. PREFACE. It may interest the reader, before perusing mis volume, to know some of the circumstances which preceded and pro duced it. • The subjects of which it treats came originally under my notice in a land where, except to the privileged foreigner, such subjects are interdicted, — at Naples, in the autumn of 1855. -

Samuel Beckett and Intermedial Performance: Passing Between

Samuel Beckett and intermedial performance: passing between Article Accepted Version McMullan, A. (2020) Samuel Beckett and intermedial performance: passing between. Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui, 32 (1). pp. 71-85. ISSN 0927-3131 doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/18757405-03201006 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/85561/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/18757405-03201006 Publisher: Brill All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Samuel Beckett and Intermedial Performance: Passing Between Anna McMullan Professor in Theatre, University of Reading [email protected] This article analyses two intermedial adaptations of works by Beckett for performance in relation to Ágnes Petho’s definition of intermediality as a border zone or passageway between media, grounded in the “inter-sensuality of perception”. After a discussion of how Beckett’s own practice might be seen as intermedial, the essay analyses the 1996 American Repertory Company programme Beckett Trio, a staging of three of Beckett’s television plays which incorporated live camera projected onto a large screen in a television studio. The second case study analyses Company SJ’s 2014 stage adaptation of a selection of Beckett’s prose texts, Fizzles, in a historic site-specific location in inner city Dublin, which incorporated projected sequences previously filmed in a different location. -

POSTMODERNISM and BECKETT's AESTHETICS of FAILURE Author(S): Laura Cerrato Source: Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui, Vol

POSTMODERNISM AND BECKETT'S AESTHETICS OF FAILURE Author(s): Laura Cerrato Source: Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui, Vol. 2, BECKETT IN THE 1990s (1993), pp. 21- 30 Published by: Brill Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25781147 Accessed: 02-04-2016 06:10 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Brill is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui This content downloaded from 132.174.254.12 on Sat, 02 Apr 2016 06:10:26 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms POSTMODERNISM AND BECKETT'S AESTHETICS OF FAILURE Is Beckett a modernist or is he a postmodernist? Probably, even before the appearance of this second term, Beckett had already chosen for himself (if we can think in terms of choice, concerning this question) when, in 1937, in his "German Letter", he decided: "Let us therefore act as the mad mathematician who used a different principle of measurement at each step of his calculation."1 But why is it suddenly so important to define Beckett in terms of Modernism or Postmodernism? Perhaps one of the reasons is that modernism has traditionally involved all the great and original writers who have transgressed the canon of their times, and because postmodernism has most often been described with regard to non-artistic and non-literary values. -

Posthuman Beckett English 9169B Winter 2019 the Course Analyzes the Short Prose That Samuel Beckett Produced Prior to and After

Posthuman Beckett English 9169B Winter 2019 The course analyzes the short prose that Samuel Beckett produced prior to and after his monumental The Unnamable (1953), a text that initiated Beckett’s deconstruction of the human subject: The Unnamable is narrated by a subject without a fully-realized body, who inhabits no identifiable space or time, who is, perhaps, dead. In his short prose Beckett continues his exploration of the idea of the posthuman subject: the subject who is beyond the category of the human (the human understood as embodied, as historically and spatially located, as possessing some degree of subjective continuity). What we find in the short prose (our analysis begins with three stories Beckett produced in 1945-6: “The Expelled,” “The Calmative,” “The End”) is Beckett’s sustained fascination with the idea of the possibility of being beyond the human: we will encounter characters who can claim to be dead (“The Calmative,” Texts for Nothing [1950-52]); who inhabit uncanny, perhaps even post-apocalyptic spaces (“All Strange Away” [1963-64], “Imagination Dead Imagine” [1965], Lessness [1969], Fizzles [1973-75]); who are unaccountably trapped in what appears to be some kind of afterlife (“The Lost Ones” [1966; 1970]); who, in fact, may even defy even the philosophical category of the posthuman (Ill Seen Ill Said [1981], Worstward Ho [1983]). And yet despite the radical dismantling of the idea or the human, as such, the being that emerges in these texts is still, perhaps even insistently, spatially, geographically, even ecologically, located. This course which finds its philosophical inspiration in the work of Martin Heidegger, especially his critical analysis of the relation between being and world, and attempts to come to some understanding of what it means for the posthuman to be in the world. -

HCR20CD Itunes Booklet

Speak, Be Silent Riot Ensemble Chaya Czernowin Anna Thorvaldsdóttir Mirela Ivičević Liza Lim Rebecca Saunders Speak, Be Silent Riot Ensemble Kate Walter – flutes [1-6] John Garner – violin [2, 4-6] Carla Rees – flute [7] Stephen Upshaw – viola [1-6] Philip Hayworth – oboe [4-6] Louise McMonagle – violincello [1-6] Ausiàs Garrigós Morant – clarinets [1-7] Marianne Schofield – double bass [4-7] Ruth Rosales – bassoon [4-6] Adam Swayne – piano [1, 3] Amy Green – saxophone [4-6] Neil Georgeson – piano [2, 4-6] Fraser Tannock – trumpet [4-6] Claudia Maria Racovicean – piano [7] Andy Connington – trombone [4-6] Anneke Hodnett – harp [4-6] Jack Adler McKean – tuba [4-6] David Royo – percussion [1-7] Sarah Saviet – violin [1-3, soloist 4-6] Aaron Holloway-Nahum – conductor Recording venue: AIR Studios, London, 7-9 September 2018 Recording producer/mixing: Moritz Bergfeld Editing/mastering: Aaron Holloway-Nahum Booklet notes: Tim Rutherford-Johnson Chaya Czernowin, Ayre … published by Schott Music Anna Thorvaldsdóttir, Ró published by Chester Music Ltd. Mirela Ivičević, Baby Magnify/Lilith’s New Toy commissioned by the Riot Ensemble Liza Lim, Speak, Be Silent published by Casa Ricordi Rebecca Saunders, Stirrings Still II published by Edition Peters Cover photograph: Francesca Rengel Design: Mike Spikin Project management: Aaron Cassidy and Sam Gillies, CeReNeM for Huddersfield Contemporary Records (HCR) in collaboration with NMC Recordings 2 At the start of her score, Ró, the Icelandic composer Anna Thorvaldsdóttir writes to her players, ‘When you see a long sustained pitch, think of it as a fragile flower that you need to carry in your hands and walk the distance on a thin rope without dropping it or falling.’ Ró is full of such ropes.