P Prepared D by MA College E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

From Dust to Dollar Gold Mining and Trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia Borderland

From Dust to Dollar Gold mining and trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia borderland [Copy and paste completed cover here} Enrico Ille, Mohamed[Copy[Copy and and paste paste Salah completed completed andcover cover here} here} Tsegaye Birhanu image here, drop from 20p5 max height of box 42p0 From Dust to Dollar Gold mining and trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia borderland Enrico Ille, Mohamed Salah and Tsegaye Birhanu Cover image: Gold washers close to Qeissan, Sudan, 25 November 2019 © Mohamed Salah This report is a product of the X-Border Local Research Network, a component of the FCDO’s Cross- Border Conflict—Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) programme, funded by UKaid from the UK government. The programme carries out research work to better understand the causes and impacts of conflict in border areas and their international dimensions. It supports more effective policymaking and development programming and builds the skills of local partners. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. The Rift Valley Institute works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2021. This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE REPORT 2 Contents Executive summary 5 1. Introduction 7 Methodology 9 2. The Blue Nile–Benishangul-Gumuz borderland 12 The two borderland states 12 The international border 14 3. Trade and mobility in the borderlands 16 The administration of trade relations 16 Constraints on mobility 18 Price differentials and borderland trade 20 Borderland relations 22 4. -

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

S P E C I a L R E P O

S P E C I A L R E P O R T FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT MISSION TO ETHIOPIA (Phase 2) Integrating the Crop and Food Supply and the Emergency Food Security Assessments 27 July 2009 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS, ROME WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME, ROME - 2 - This report has been prepared by Mario Zappacosta, Jonathan Pound and Prisca Kathuku, under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP Secretariats. It is based on information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned if further information is required. Henri Josserand Mustapha Darboe Deputy Director, GIEWS, FAO Regional Director for Southern, Eastern Fax: 0039-06-5705-4495 and Central Africa, WFP E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 0027-11-5171634 E-mail: : [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web (www.fao.org ) at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Special Alerts/Reports can also be received automatically by E-mail as soon as they are published, by subscribing to the GIEWS/Alerts report ListServ. To do so, please send an E-mail to the FAO-Mail-Server at the following address: [email protected] , leaving the subject blank, with the following message: subscribe GIEWSAlertsWorld-L To be deleted from the list, send the message: unsubscribe GIEWSAlertsWorld-L Please note that it is now possible to subscribe to regional lists to only receive Special Reports/Alerts by region: Africa, Asia, Europe or Latin America (GIEWSAlertsAfrica-L, GIEWSAlertsAsia-L, GIEWSAlertsEurope-L and GIEWSAlertsLA-L). -

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Journal of Ethnobiology and provided by PubMed Central Ethnomedicine BioMed Central Research Open Access Ethnomedical survey of Berta ethnic group Assosa Zone, Benishangul-Gumuz regional state, mid-west Ethiopia Teferi Flatie1, Teferi Gedif1, Kaleab Asres*2 and Tsige Gebre-Mariam1 Address: 1Department of Pharmaceutics, School of Pharmacy, Addis Ababa University, PO Box 1176, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and 2Department of Pharmacognosy, School of Pharmacy, Addis Ababa University, PO Box 1176, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Email: Teferi Flatie - [email protected]; Teferi Gedif - [email protected]; Kaleab Asres* - [email protected]; Tsige Gebre- Mariam - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 1 May 2009 Received: 17 June 2008 Accepted: 1 May 2009 Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2009, 5:14 doi:10.1186/1746-4269-5-14 This article is available from: http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/5/1/14 © 2009 Flatie et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Traditional medicine (TM) has been a major source of health care in Ethiopia as in most developing countries around the world. This survey examined the extent and factors determining the use of TM and medicinal plants by Berta community. One thousand and two hundred households (HHs) and fourteen traditional healers were interviewed using semi-structured questionnaires and six focused group discussions (FGDs) were conducted. -

From Dust to Dollar Gold Mining and Trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia Borderland

From Dust to Dollar Gold mining and trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia borderland [Copy and paste completed cover here} Enrico Ille, Mohamed[Copy[Copy and and paste paste Salah completed completed andcover cover here} here} Tsegaye Birhanu image here, drop from 20p5 max height of box 42p0 From Dust to Dollar Gold mining and trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia borderland Enrico Ille, Mohamed Salah and Tsegaye Birhanu Cover image: Gold washers close to Qeissan, Sudan, 25 November 2019 © Mohamed Salah This report is a product of the X-Border Local Research Network, a component of the FCDO’s Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) programme, funded by UK aid from the UK government. XCEPT brings together leading experts to examine conflict-affected borderlands, how conflicts connect across borders, and the factors that shape violent and peaceful behaviour. The X-Border Local Research Network carries out research to better understand the causes and impacts of conflict in border areas and their international dimensions. It supports more effective policymaking and development programming and builds the skills of local partners. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. The Rift Valley Institute works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2021. This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE REPORT 2 Contents Executive summary 5 1. Introduction 7 Methodology 9 2. The Blue Nile–Benishangul-Gumuz borderland 12 The two borderland states 12 The international border 14 3. -

Implications of Land Deals to Livelihood Security and Natural Resource Management in Benshanguel Gumuz Regional State, Ethiopia by Maru Shete

Implications of land deals to livelihood security and natural resource management in Benshanguel Gumuz Regional State, Ethiopia by Maru Shete Paper presented at the International Conference on Global Land Grabbing 6-8 April 2011 Organised by the Land Deals Politics Initiative (LDPI) in collaboration with the Journal of Peasant Studies and hosted by the Future Agricultures Consortium at the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex Implications of land deals to livelihood security and natural resource management in Benshanguel Gumuz Regional State, Ethiopia 1 (Draft not for citation) Maru Shete Future Agricultures Consortium Research Fellow, P.O.Box 50321, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Email: [email protected] Abstract The Federal Government of Ethiopia (FGE) is leasing out large tracts of arable lands both to domestic and foreign investors in different parts of the country where land is relatively abundant. While the FGE justifies that it is part of the country’s strategy to achieve food security objective, critics have been forwarded from different directions. This research aims at studying the implications of land deals to livelihood security and natural resource management in Benshanguel Gumuz Regional State. Exploratory study was done and data were collected through interviewing 150 farm households in two districts of the region. Key informants interview and focus group discussions were also held to generate required data. Primary data were complemented with secondary data sources. Preliminary findings suggest that there is weak linkage, monitoring and support of investment activities from federal, regional and district levels, weak capacity of domestic investors, accelerated degradation of forest resources, and threatened livelihood security of community members. -

Census Data/Projections, 1999 & 2000

Census data/Projections, 1999 & 2000 Jan - June and July - December Relief Bens., Supplementary Feeding Bens. TIGRAY Zone 1994 census 1999 beneficiaries - May '99 2000 beneficiaries - Jan 2000 July - Dec 2000 Bens Zone ID/prior Wereda Total Pop. 1999 Pop. 1999 Bens. 1999 bens % 2000 Pop. 2000 Bens 2000 bens Bens. Sup. July - Dec Bens July - Dec Bens ity Estimate of Pop. Estimate % of Pop. Feeding % of pop 1 ASEGEDE TSIMBELA 96,115 111,424 114,766 1 KAFTA HUMERA 48,690 56,445 58,138 1 LAELAY ADIYABO 79,832 92,547 5,590 6% 95,324 7,800 8% 11,300 12% Western 1 MEDEBAY ZANA 97,237 112,724 116,106 2,100 2% 4,180 4% 1 TAHTAY ADIYABO 80,934 93,825 6,420 7% 96,639 18,300 19% 24,047 25% 1 TAHTAY KORARO 83,492 96,790 99,694 2,800 3% 2,800 3% 1 TSEGEDE 59,846 69,378 71,459 1 TSILEMTI 97,630 113,180 37,990 34% 116,575 43,000 37% 15,050 46,074 40% 1 WELKAIT 90,186 104,550 107,687 Sub Total 733,962 850,863 50,000 6% 876,389 74,000 8% 15,050 88,401 10% *2 ABERGELE 58,373 67,670 11,480 17% 69,700 52,200 75% 18,270 67,430 97% *2 ADWA 109,203 126,596 9,940 8% 130,394 39,600 30% 13,860 58,600 45% 2 DEGUA TEMBEN 89,037 103,218 7,360 7% 106,315 34,000 32% 11,900 44,000 41% Central 2 ENTICHO 131,168 152,060 22,850 15% 156,621 82,300 53% 28,805 92,300 59% 2 KOLA TEMBEN 113,712 131,823 12,040 9% 135,778 62,700 46% 21,945 67,700 50% 2 LAELAY MAYCHEW 90,123 104,477 3,840 4% 107,612 19,600 18% 6,860 22,941 21% 2 MEREB LEHE 78,094 90,532 14,900 16% 93,248 57,500 62% 20,125 75,158 81% *2 NAEDER ADET 84,942 98,471 15,000 15% 101,425 40,800 40% 14,280 62,803 62% 2 -

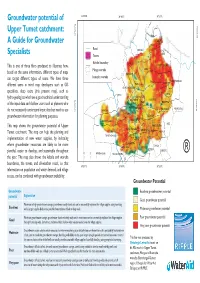

Groundwater Potential of Upper Tumet Catchment

Groundwater potential of 34°30'0"E 34°40'0"E 34°50'0"E Upper Tumet catchment: To Gizen 10°30'0"N BEBE BEBE 10°30'0"N SAEDA A Guide for Groundwater BEBE TOBE Road SHOGEL Specialists Towns BEBE Kebele boundary MALLO This is one of three fliers produced to illustrate how, TUMET MEKUWAR Menge woreda BENE based on the same information, different types of maps EWADANE can target different types of users. We have three komesha woreda BALGAL TUMET MENDERA different users in mind: map developers such as GIS MANAJA ALFASHER GUAGUYO BERBER specialists, deep users (this present map), such as JEMEA HALFA hydro-geologists who have a good technical understanding KUDIYU 02 BELL FERFER KUDIYU 01 Menge BALA FAYA of the input data and shallow users such as planners who ABORA KESHEFA DIGNIDO BELDIWESA ABUNDUDU 10°20'0"N do not necessarily understand input data but need to use 10°20'0"N ASHURA METEMA TSLENGER groundwater information for planning purposes. AUSHMEN TUMET ALGELA KARTUM AZIZ TUMET JEDEDA This map shows the groundwater potential of Upper OBE TUMET MENGDEL ABJINDO Tumet catchment. The map can help the planning and TUMET BARIA AFIGALA TUMET ADMUGU GOSHO implementation of new water supplies, by indicating HOLO ABAGUSHA where groundwater resources are likely to be more SHAGA KELSHE YEJIE MEGELE KETEMA plentiful, easier to develop, and sustainable throughout FATSKO SHEKETO 036Kilometers TSRA ALMETEMA ® the year; The map also shows the kebele and woreda o Asosa boundaries, the towns, and all-weather roads, so that T 34°30'0"E 34°40'0"E 34°50'0"E information on population and water demand, and village access, can be combined with groundwater availability. -

Oromia Region Administrative Map(As of 27 March 2013)

ETHIOPIA: Oromia Region Administrative Map (as of 27 March 2013) Amhara Gundo Meskel ! Amuru Dera Kelo ! Agemsa BENISHANGUL ! Jangir Ibantu ! ! Filikilik Hidabu GUMUZ Kiremu ! ! Wara AMHARA Haro ! Obera Jarte Gosha Dire ! ! Abote ! Tsiyon Jars!o ! Ejere Limu Ayana ! Kiremu Alibo ! Jardega Hose Tulu Miki Haro ! ! Kokofe Ababo Mana Mendi ! Gebre ! Gida ! Guracha ! ! Degem AFAR ! Gelila SomHbo oro Abay ! ! Sibu Kiltu Kewo Kere ! Biriti Degem DIRE DAWA Ayana ! ! Fiche Benguwa Chomen Dobi Abuna Ali ! K! ara ! Kuyu Debre Tsige ! Toba Guduru Dedu ! Doro ! ! Achane G/Be!ret Minare Debre ! Mendida Shambu Daleti ! Libanos Weberi Abe Chulute! Jemo ! Abichuna Kombolcha West Limu Hor!o ! Meta Yaya Gota Dongoro Kombolcha Ginde Kachisi Lefo ! Muke Turi Melka Chinaksen ! Gne'a ! N!ejo Fincha!-a Kembolcha R!obi ! Adda Gulele Rafu Jarso ! ! ! Wuchale ! Nopa ! Beret Mekoda Muger ! ! Wellega Nejo ! Goro Kulubi ! ! Funyan Debeka Boji Shikute Berga Jida ! Kombolcha Kober Guto Guduru ! !Duber Water Kersa Haro Jarso ! ! Debra ! ! Bira Gudetu ! Bila Seyo Chobi Kembibit Gutu Che!lenko ! ! Welenkombi Gorfo ! ! Begi Jarso Dirmeji Gida Bila Jimma ! Ketket Mulo ! Kersa Maya Bila Gola ! ! ! Sheno ! Kobo Alem Kondole ! ! Bicho ! Deder Gursum Muklemi Hena Sibu ! Chancho Wenoda ! Mieso Doba Kurfa Maya Beg!i Deboko ! Rare Mida ! Goja Shino Inchini Sululta Aleltu Babile Jimma Mulo ! Meta Guliso Golo Sire Hunde! Deder Chele ! Tobi Lalo ! Mekenejo Bitile ! Kegn Aleltu ! Tulo ! Harawacha ! ! ! ! Rob G! obu Genete ! Ifata Jeldu Lafto Girawa ! Gawo Inango ! Sendafa Mieso Hirna -

190327 Oromia Region Agric S

ETHIOPIA: AGRICULTURE SECTOR HRP OROMIA REGION MONTHLY DASHBOARD - March 2019 The devastating impact on agriculture following consecutive years of drought in Ethiopia is undisputed. While forecasts for 2019 indicate a probability of normal to above normal rain in most parts of Ethiopia, in east, south and southeastern regions, the upcoming rainy season (March to June) is forecast- KEY FIGURES ed to be average or below average. In areas where normal to above normal rains are expected, recovery will not be spontaneous, as previous OVERVIEW HOUSEHOLDS REACHED drought-affected households are likely to require sustained humanitarian assistance as a result of exhausted coping mechanisms. HOUSEHOLDS IN NEED Humanitarian assistance for IDPs and IDP returnees is largely dependent on IDPs’ access to land and the livelihood assets they have been able to 1.15 million maintain during displacement. Emergency feed and animal health interventions are needed to reduce the burden on the resources of the host 0.0m 0% communities and prevent the spread of diseases, especially for animals displaced across regional borders. Where appropriate, land will be availed and crop seeds, farming tools, and training will be provided to support IDP and returning households to improve their food security and reduce the burden HOUSEHOLDS TARGETED on host Communities. 658,428 IDP HOUSEHOLDS TARGETED N_Shewa 0m 0% Horo 64,195 Guduru Chinaksen Guto W_Wellega Gida Meta Sasiga Finfine Doba Gursum AGRICULTURE LIVESTOCK E_Wellega Mieso Crop Seeds &Tools W_Shewa Special Girawa -

Value Chain Analysis of Teff in East Wollega, Ethiopia

www.jard.edu.pl http://dx.doi.org/10.17306/J.JARD.2021.01313 Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development pISSN 1899-5241 1(59) 2021, 17–28 eISSN 1899-5772 Accepted for print: 3.12.2020 VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS OF TEFF IN EAST WOLLEGA, ETHIOPIA Temesgen Kabeta1, Jema Haji2, Rijalu Negash3 1Gambella University, Ethiopia 2Haramaya University, Ethiopia 3Jimma University, Ethiopia Abstract. This study attempted to analyze the teff value chain INTRODUCTION in the Jimma Arjo District of East Wollega Zone, Western Ethiopia. The multistage sampling technique was employed A value chain is crucial in enforcing standards, with to draw a sample of 123 teff producers, purposively selected each actor ensuring that the product originating from the 55 traders and 15 consumers. Both quantitative and qualita- previous stage meets the criteria. According to Bekabil tive data were collected from primary and secondary sources using pre-tested structured questionnaires and checklists. De- et al. (2011), the teff value chain program helps to dou- scriptive statistics and Kendall’s coefficient of concordance ble teff production. It ensures that farmers have access were applied to analyze data. Results showed that the main to sufficient markets to capture the highest value for teff value chain actors in the study area included input sup- their product. It also increases incomes and reduces the pliers, producers, local collectors, wholesalers, retailers, and price paid by consumers within five years. consumers. In the district, there were no proper upgrading In Ethiopia, land used for teff production during the practices and governance systems in the teff value chain. The 2017 production year was estimated at 3.02 million hec- predicted probability that teff producers choose local collec- tares, and 50.2 million quintals were produced with the tors, wholesalers, retailers, and consumer outlets amounted productivity of 16.64 quintals per hectare of land.