Imperial Looting and the Case of Benin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Festival Events 1

H.E. Lieutenant-General Olusegun Obasanjo, Head of State of Nigeria and Festival Patron. (vi) to facilitate a periodic 'return to origin' in Africa by Black artists, writers and performers uprooted to other continents. VENUE OFEVENTS The main venue is Lagos, capital of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. But one major attraction, the Durbar. will take place in Kaduna, in the northern part basic facts of the country. REGISTRATION FEES Preparations are being intensified for the Second World There is a registration fee of U.S. $10,000 per partici- Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture to be held pating country or community. in Nigeria from 15th January to 12th February, 1977. The First Festival was held in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966. GOVERNING BODY It was then known simply as the World Festival of Negro The governing body for the Festival is the International Arts. Festival Committee representing the present 16 Festival At the end of that First Festival in 1966, Nigeria was Zones into which the Black African world has been invited to host the Second Festival in 1970. Nigeria divided. These 16 Zones are: South America, the accepted the invitation, but because of the internal Caribbean countries, USA/Canada, United Kingdom and situation in the country, it was not possible to hold the Ireland, Europe, Australia/Asia, Eastern Africa, Southern Festival that year. Africa, East Africa (Community), Central Africa I and II, At the end of the Nigerian civil war, the matter was WestAfrica (Anglophone), West Africa (Francophone) I resuscitated, and the Festival was rescheduled to be held and II, North Africa and the Liberation Movements at the end of 1975. -

Benin Kingdom • Year 5

BENIN KINGDOM REACH OUT YEAR 5 name: class: Knowledge Organiser • Benin Kingdom • Year 5 Vocabulary Oba A king, or chief. Timeline of Events Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means 900 CE Lots of villages join together and make a “Rulers of the Sky”. kingdom known as Igodomigodo, ruled by Empire lots of countries or states, all ruled by the Ogiso. one monarch or single state. c. 900- A huge earthen moat was constructed Guild A group of people who all do the 1460 CE around the kingdom, stretching 16.000 km same job, usually a craft. long. Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 1180 CE The Oba royal family take over from the Voodoo The belief that non-human objects Osigo, and begin to rule the kingdom. (or Vodun) have spirits or souls. They are treated like Gods. Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as 1440 CE Benin expands its territory under the rule of Oba Ewuare the Great. a kind of money to trade with African leaders. 1470 CE Oba Ewuare renames the kingdom as Civil war A war between people who live in the Edo, with it;s main city known as Ubinu (Benin in Portuguese). same country. Moat A long trench dug around an area to 1485 CE The Portuguese visit Edo and Ubinu. keep invaders out. 1514 CE Oba Esigie sets up trading links with the Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Portuguese, and other European visitors. country by force, and live among the 1700 CE A series of civil wars within Benin lead to people. -

Stampmanage Database

StampManage Database - # of stamp varieties & images grouped by Country Abu Dhabi - 348 Values 82 Total Stamps: 89 --- Total Images 85 --- Total Andorra - French Admin. - 372 Values 122 Total Stamps: 941 --- Total Images 587 --- Total Aden - 349 Values 754 Total Stamps: 101 --- Total Images 98 --- Total Andorra - Spanish Admin. - 910 Values 267 Total Stamps: 437 --- Total Images 326 --- Total Afars and Issas, The French Territory Values 340 of the - 351 Angola - 373 Total Stamps: 294 --- Total Images 180 --- Total Total Stamps: 2170 --- Total Images 1019 --- Values 27 Total Values 1580 Afghanistan - 352 Angra - 374 Total Stamps: 2184 --- Total Images 1768 --- Total Stamps: 48 --- Total Images 42 --- Total Total Values 3485 Values 101 Aitutaki - 354 Anguilla - 375 Total Stamps: 1191 --- Total Images 934 --- Total Stamps: 1468 --- Total Images 1173 --- Total Values 1303 Total Values 365 Ajman - 355 Anjouan - 376 Total Stamps: 772 --- Total Images 441 --- Total Total Stamps: 36 --- Total Images 30 --- Total Values 254 Values 74 Alaouites - 357 Annam and Tonkin - 377 Total Stamps: 139 --- Total Images 77 --- Total Total Stamps: 14 --- Total Images 6 --- Total Values 242 Values 28 Albania - 358 Antigua - 379 Total Stamps: 3919 --- Total Images 3266 --- Total Stamps: 6607 --- Total Images 1273 --- Total Values 1873 Total Values 876 Alderney - 359 Argentina - 382 Total Stamps: 848 --- Total Images 675 --- Total Total Stamps: 5002 --- Total Images 2770 --- Values 88 Total Values 7076 Alexandretta - 362 Armenia - 385 Total Stamps: 32 --- Total -

1946 Colonel the Honourable Sir Leslie Orme WILSON GCSI, GCMG

Colonel The Honourable SIR LESLIE ORME WILSON GCSI, GCMG, GCIE, DSO [1 August 1876 – 29 September 1955] Sir Leslie was Patron of the Club from 1933 to 1946 Sir Leslie was elected to Life Membership of the Club in 1946. Sir Leslie Orme Wilson (1876-1955), soldier, politician and Governor, was born on 1 August 1876 in London, son of Henry Wilson, stockbroker, and his wife Ada Alexandrina (née Orme). Educated at St Michael's School, Westgate, and St Paul's School, London, he was appointed second lieutenant in the Royal Marine Light Infantry in 1895, promoted to lieutenant in 1896 and captain in 1901. After serving (1899-1901) in the South African War in which he was wounded, mentioned in dispatches, and awarded the Queen's Medal with five clasps and the Distinguished Service Order, he was aide-de-camp (1903-09) to Sir Harry Rawson (Governor of New South Wales). On 10 June 1909 at Christ Church, Mayfair, London, Wilson married Winifred May, eldest daughter of Charles Smith, a Sydney merchant. While a captain of the Berkshire Royal Artillery (Territorials), Wilson ran for election in 1913, won Reading, and took his seat in the House of Commons in early 1914. We thank the History Interest Group and other volunteers who have researched and prepared these Notes. The series will be progressively expanded and developed. They are intended as casual reading for the benefit of Members, who are encouraged to advise of any inaccuracies in the material. Please do not reproduce them or distribute them outside of the Club membership. -

What Was Life Like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’S Enquiry: Why Is It Important to Learn About Benin in School?

History Our main enquiry question this term: What was life like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’s enquiry: Why is it important to learn about Benin in school? Benin Where is Benin? Benin is a region in Nigeria, West Africa. Benin was once a civilisation of cities and towns, powerful Kings and a large empire which traded over long distances. The Benin Empire 900-1897 Benin began in the 900s when the Edo people settled in the rainforests of West Africa. By the 1400s they had created a wealthy kingdom with a powerful ruler, known as the Oba. As their kingdom expanded they built walls and moats around Benin City which showed incredible town planning and architecture. What do you think of Benin City? Benin craftsmen were skilful in Bronze and Ivory and had strong religious beliefs. During this time, West Africa invented the smelting (heating and melting) of copper and zinc ores and the casting of Bronze. What do you think that this might mean? Why might this be important? What might this invention allowed them to do? This allowed them to produced beautiful works of art, particularly bronze sculptures, which they are famous for. Watch this video to learn more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zpvckqt/articles/z84fvcw 7 Benin was the center of trade. Europeans tried to trade with Benin in the 15 and 16 century, especially for spices like black pepper. When the Europeans arrived 8 Benin’s society was so advanced in what they produced compared with Britain at the time. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

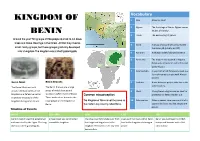

Kingdom of Benin Is Not the Same As 10 Colonisation When Invaders Take Over Control of a Benin

KINGDOM OF Vocabulary 1 Oba A king or chief. 2 Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means BENIN ‘Rulers of the Sky’. 3 Trade The exchanging of goods. Around the year 900 groups of Edo people started to cut down trees and make clearings in the forest. At first they lived in 4 Guild A group of people who all complete small family groups, but these groups gradually developed the same job (usually a craft). into a kingdom. The kingdom was called Igodomigodo. 5 Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 6 Benin city The modern city located in Nigeria. Previously, it has been called Edo and Igodomigodo. 7 Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as a form of money to trade with African leaders. Benin Moat Benin Bronzes 8 Civil war A war between people who live in the same country. The Benin Moat was built The Benin Bronzes are a large around the boundaries of the group of metal plaques and 9 Moat A long trench dug around an area for kingdom as a defensive barrier sculptures (often made of brass). Common misconception protection to keep invaders out. to protect the people of the These works of art decorate the kingdom during times of war. royal palace of the Kingdom of The Kingdom of Benin is not the same as 10 Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Benin. the modern day country called Benin. country by force, and live among the people. Timeline of Events 900 AD 900—1460 1180 1700 1897 Benin Kingdom was first established A huge moat was constructed The Oba royal family take over from A series of civil wars within Benin Benin was destroyed by British and was ruled by the Ogiso. -

1 Ancient America and Africa

NASH.7654.cp01.p002-035.vpdf 9/1/05 2:49 PM Page 2 CHAPTER 1 Ancient America and Africa Portuguese troops storm Tangiers in Morocco in 1471 as part of the ongoing struggle between Christianity and Islam in the mid-fifteenth century Mediterranean world. (The Art Archive/Pastrana Church, Spain/Dagli Orti) American Stories Four Women’s Lives Highlight the Convergence of Three Continents In what historians call the “early modern period” of world history—roughly the fif- teenth to the seventeenth century, when peoples from different regions of the earth came into close contact with each other—four women played key roles in the con- vergence and clash of societies from Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Their lives highlight some of this chapter’s major themes, which developed in an era when the people of three continents began to encounter each other and the shape of the mod- ern world began to take form. 2 NASH.7654.cp01.p002-035.vpdf 9/1/05 2:49 PM Page 3 CHAPTER OUTLINE Born in 1451, Isabella of Castile was a banner bearer for reconquista—the cen- The Peoples of America turies-long Christian crusade to expel the Muslim rulers who had controlled Spain for Before Columbus centuries. Pious and charitable, the queen of Castile married Ferdinand, the king of Migration to the Americas Aragon, in 1469.The union of their kingdoms forged a stronger Christian Spain now Hunters, Farmers, and prepared to realize a new religious and military vision. Eleven years later, after ending Environmental Factors hostilities with Portugal, Isabella and Ferdinand began consolidating their power. -

4 P H I L a T E L I C C H R O N I C L E ...A N D F L D O E R T I S E R

. O r • ♦ 4 " 4 * 4 - Philatelic Chronicle . .V X♦ * -AK*- ♦ . and fldoertiser. t 4 * VOLUME VIII. ( 1 8 9 8 — 18 9 9 . > /J s- A >’ & A 4 ^ 4 * 4 * X A * r A V M i 4 ^ t r R I M F n i,’»lt JHK Ji A lt ^ y A 4 * K A NDAL 1- il K U T 11 L IM, A s t o s P i u n t i m . W o r k s , A r t v s t r o s s . B iiim is i. h \m . 4 * X t a :.ii 1 i r-tistil.r m A 4- * r 'MIL I’ ll 1 L A 1 LL i ( i’ l' |; L I 5 11 I N G Co, * 4 t i F u M'HAM U u AU, H a MJSUu Ii i h , IJ IKMINL-HAM. 4-’> r 4 - 4 ^ A ' A j # 7^ tv. THE PHILATELIC CHRONICLE AND ADVERTISER. COMPARE OUR PRICES WITH OTHER DEALERS’1 M IDLAND 5TAM P CO., 11, Norttiam pton St*, B IR M IN G H A M , UNUSED STAMPS. CHEAP SETS. 1 1 2 i set. Doz. sets. 8. d. 3. d . s . d . a. d . British Beohuanaland, surcharged on Bavaria, 17 variouB . 0 5 4 0 English, |d., Id., 2d., 4d., 6d. and Borneo, 1897, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 .. 0 10 9 6 1/-, set of 6 3 6 Brazil, 22 various.. .. 0 10 7 0 Dominica, Id. .; 1 4 Belgium, 40 various . 0 6 5 6 „ *d. -

Sir Frederick Lugard, World War I and the Amalgamation of Nigeria 1914-1919

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1966 Sir Frederick Lugard, World War I and the Amalgamation of Nigeria 1914-1919 John F. Riddick Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Riddick, John F., "Sir Frederick Lugard, World War I and the Amalgamation of Nigeria 1914-1919" (1966). Master's Theses. 3848. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3848 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIR FREDERICK LUGARD, WORLD WAR I. AND - THE AMALGAMATION OF NIGERIA 1914-1919/ by John I<'. Riddick A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August, 1966 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation for the co-operation of the following research institutions: Boston University Library, Boston, Massachusetts Kalamazoo College Library, Kalamazoo, Michigan Michigan State University Library, East Lansing, Michigan Northwestern University Library, Evanston, Illinois The University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan The Western Michigan University Library, Kalamazoo, Michigan I am most grateful for the encouragement, advice, and criticism of' Dr. H. Nicholas Hamner, who directed the entire project. A debt of thanks is also due to Mrs. Ruth Allen, who typed the finished product, and to my wife, who assisted me in every way. -

Zimbabwe: Getting the Transition Back on Track

THE SWAMPS OF INSURGENCY: NIGERIA’S DELTA UNREST Africa Report N°115 – 3 August 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 1 II. COMMODITIES, COMMUNITIES AND CONFLICT ............................................. 2 A. A LEGACY OF MILITANCY AND UNDERDEVELOPMENT ........................................................2 1. Slavery, palm oil and colonial control ........................................................................2 2. Isaac Boro’s twelve-day revolt ...................................................................................4 3. Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni struggle .....................................................................4 B. THE SECURITY FORCES..........................................................................................................5 1. Umuechem, Odi and Odioma .....................................................................................6 2. Oil company surveillance and security force payments ..............................................7 III. ADMINISTRATION, TRANSPARENCY AND RESPONSIBILITY...................... 12 A. OIL COMPANY DEVELOPMENT EFFORTS ..............................................................................12 1. Chevron, women’s protests and ethnic violence ..........................................................14 2. The European Commission, Pro-Natura and the “participatory -

The Spouses of the Governors of Queensland Credits and Acknowledgements

The Spouses of the Governors of Queensland Credits and Acknowledgements Cover design – portraits of the © The State of Queensland, Australia (Office of the Governor). spouses of the Governors of First edition published May 2018, revised edition published November 2018. Queensland since 1859. Copyright protects this publication except for purposes permitted by the The Office of the Governor expresses Copyright Act. Reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without prior its sincere gratitude to the State written permission of the Office of the Governor. Reference to this publication is Library of Queensland for granting permitted only with appropriate acknowledgement. permission to reproduce items from its photographic collection. Every effort has been made to ensure the information and facts in this book are The portrait of Lady Abel Smith is correct but the publishers hereby disclaim any liability for incorrect information. reproduced with permission from the Government House, Queensland – www.govhouse.qld.gov.au National Portrait Gallery, London. ISBN 978-0-646-98873-3. Contents Governor’s Foreword 2 Introduction 3 Lady Bowen 4 The Marchioness of Normanby 6 Lady Musgrave 8 Lady Norman 10 Lady Lamington 12 Lady Chermside 14 Lady Chelmsford 16 Lady MacGregor 18 Lady Goold-Adams 20 Lady Goodwin 22 Lady Wilson 24 Lady Lavarack 26 Lady Abel Smith 28 Lady Mansfield 30 Lady Hannah 32 Lady Ramsay 34 Lady Campbell 36 Mr Angus McDonald 38 Mrs Barbara Arnison 40 Mr Michael Bryce AM AE 42 Mr Stuart McCosker 44 Bachelors and Widowers 46 [1] Governor’s Foreword arly in 2014, Kaye was invited to speak at the official opening of the Annual EForum on Women and Homelessness, hosted by The Lady Musgrave Trust.