The Hong Kong Week of 1967 and the Emergence of the Modern Hong Kong Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coin Cart Schedule (From 2014 to 2020) Service Hours: 10 A.M

Coin Cart Schedule (From 2014 to 2020) Service hours: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. (* denotes LCSD mobile library service locations) Date Coin Cart No. 1 Coin Cart No. 2 2014 6 Oct (Mon) to Kwun Tong District Kwun Tong District 12 Oct (Sun) Upper Ngau Tau Kok Estate Piazza Upper Ngau Tau Kok Estate Piazza 13 Oct (Mon) to Yuen Long District Tuen Mun District 19 Oct (Sun) Ching Yuet House, Tin Ching Estate, Tin Yin Tai House, Fu Tai Estate Shui Wai * 20 Oct (Mon) to North District Tai Po District 26 Oct (Sun) Wah Min House, Wah Sum Estate, Kwong Yau House, Kwong Fuk Estate * Fanling * (Service suspended on Tuesday 21 October) 27 Oct (Mon) to Wong Tai Sin District Sham Shui Po District 2 Nov (Sun) Ngan Fung House, Fung Tak Estate, Fu Wong House, Fu Cheong Estate * Diamond Hill * (Service suspended on Friday 31 October) (Service suspended on Saturday 1 November) 3 Nov (Mon) to Eastern District Wan Chai District 9 Nov (Sun) Oi Yuk House, Oi Tung Estate, Shau Kei Lay-by outside Causeway Centre, Harbour Wan * Drive (Service suspended on Thursday 6 (opposite to Sun Hung Kai Centre) November) 10 Nov (Mon) to Kwai Tsing District Islands District 16 Nov (Sun) Ching Wai House, Cheung Ching Estate, Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate, Tung Tsing Yi * Chung * (Service suspended on Monday 10 November and Wednesday 12 November) 17 Nov (Mon) to Kwun Tong District Sai Kung District 23 Nov (Sun) Tsui Ying House, Tak Chak House, Tsui Ping (South) Estate * Hau Tak Estate, Tseung Kwan O * (Service suspended on Tuesday 18 November) 24 Nov (Mon) to Sha Tin District Tsuen Wan -

Annual Report 2015 Annual Report 2015

C h i na Air c ra f t L ea si n g G r o u p Ho l d i n gs Li mite d FULL VALUE-CHAIN AIRCRAFT SOLUTION PROVIDER www.calc.com.hk ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 REPORT ANNUAL (Incorporated under the laws of the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock code : 01848 ck.ng 04832_E01_IFC+Content_4C Time/date: 08-04-2016_06:18:53 China Aircraft Leasing Group Holdings Limited CALC AT A GLANCE 65 107 172 Aircraft fleet Aircraft on order with Aircraft in 2022 (as at 22 Mar 2016) Airbus (as at 22 Mar 2016) 3.5yrs 10yrs Over 20% Average fleet age Average remaining Market share of Airbus (as at 31 Dec 2015) lease term A320 series aircraft deliveries in China market in 2015 A constituent stock of the HK$23.9b 1st MSCI Listed aircraft lessor China Small Cap Total assets in Asia (as at 31 Dec 2015) Index A constituent stock of the Hang Seng Over 110 Global Composite Index Staff with 9 offices and the Hang Seng worldwide Composite Index 2 ck.ng 04832_E01_IFC+Content_4C Time/date: 08-04-2016_06:18:53 Annual Report 2015 CONTENTS 13 Company Profile 14 Financial Highlights and Five-Year Financial Summary 16 Major Achievements 18 Chairman Statement 21 Management Discussion and Analysis 29 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 49 Corporate Governance Report 59 Report of the Directors 74 Profile of the Directors and Senior Management 81 Independent Auditor's Report 83 Consolidated Balance Sheet 84 Consolidated Statement of Income 85 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 86 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 88 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 89 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 163 Corporate Information 1 ck.ng 04832_E02_All Divider+company profile_4C Time/date: 08-04-2016_06:18:53 China Aircraft Leasing Group Holdings Limited LEADING THE WAY CALC is a pioneer and a market leader in China’s aircraft leasing industry. -

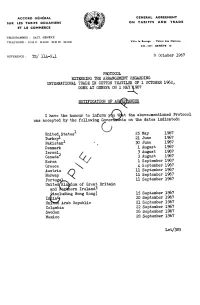

9 October 1967 PROTOCOL EXTENDING the ARRANGEMENT

ACCORD GÉNÉRAL GENERAL AGREEMENT SUR LES TARIFS DOUANIERS ON TARIFFS AND TRADE ET LE COMMERCE m TELEGRAMMES : GATT, GENÈVE TELEPHONE: 34 60 11 33 40 00 33 20 00 3310 00 Villa le Bocage - Palais des Nations CH-1211 GENÈVE tO REFERENCE : TS/ 114--5*! 9 October 1967 PROTOCOL EXTENDING THE ARRANGEMENT REGARDING INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN COTTON TEXTILES OF 1 OCTOBER 1962, DONE AT GENEVA ON 1 MAY U967 NOTIFICATION OF ACCEPTANCES I have the honour to inform yew. tHat the above-mentioned Protocol was accepted by the following Governments on the dates indicated: United States G 25 May 1967 Turkeys- 21 June 1967 Pakistan 30 June 1967 Denmark 1 August 1967 Israel, 3 August 1967 Canada* 3 August 1967 Korea 1 September 1967 Greece U September 1967 Austria 11 September 1967 Norway 11 September 1967 Portuga 11 Septembei• 1967 United/kinkdom of Great Britain and ItacAnern Ireland^ ^including Hong Kong) 15 September 1967 Irttia^ 20 September 1967 Unrtrea Arab Republic 21 September 1967 Colombia 22 September 1967 Sweden 26 September 1967 Mexico 28 September 1967 Let/385 - 2 - Republic of China 28 September 1967 Finland 29 September 1967 Belgium 29 September 1967 France 29 September 1967 Germany, Federal Republic 29 September 1967 Italy 29 September 1967 Luxemburg 29 September 1967 Netherlands, Kingdom of the (for its European territory only) 29 September 1967 Japan ,. 30 September 1967 Australia 30 September 1967 Jamaica 2 October 1967 Spain 3 October 1967 Acceptance by the Governments of Italy and of the Federal Republic of Germany was made subject to ratification. The Protocol entered into force on 1 October 1967, pursuant to its paragraph 5. -

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History Modern Hong Kong Steve Tsang Subject: China, Hong Kong, Macao, and/or Taiwan Online Publication Date: Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.280 Abstract and Keywords Hong Kong entered its modern era when it became a British overseas territory in 1841. In its early years as a Crown Colony, it suffered from corruption and racial segregation but grew rapidly as a free port that supported trade with China. It took about two decades before Hong Kong established a genuinely independent judiciary and introduced the Cadet Scheme to select and train senior officials, which dramatically improved the quality of governance. Until the Pacific War (1941–1945), the colonial government focused its attention and resources on the small expatriate community and largely left the overwhelming majority of the population, the Chinese community, to manage themselves, through voluntary organizations such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The 1940s was a watershed decade in Hong Kong’s history. The fall of Hong Kong and other European colonies to the Japanese at the start of the Pacific War shattered the myth of the superiority of white men and the invincibility of the British Empire. When the war ended the British realized that they could not restore the status quo ante. They thus put an end to racial segregation, removed the glass ceiling that prevented a Chinese person from becoming a Cadet or Administrative Officer or rising to become the Senior Member of the Legislative or the Executive Council, and looked into the possibility of introducing municipal self-government. -

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü Duo 女鐸, 1912–1951

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü duo 女鐸, 1912–1951 Zhou Yun A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University February 2019 © Copyright by Zhou Yun 2019 All Rights Reserved Except where otherwise acknowledged, this thesis is my own original work. Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Benjamin Penny for his valuable suggestions and constant patience throughout my five years at The Australian National University (ANU). His invitation to study for a Doctorate at Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) not only made this project possible but also kindled my academic pursuit of the history of Christianity. Coming from a research background of contemporary Christian movements among diaspora Chinese, I realise that an appreciation of the present cannot be fully achieved without a thorough study of the past. I was very grateful to be given the opportunity to research the Republican era and in particular the development of Christianity among Chinese women. I wish to thank my two co-advisers—Dr. Wei Shuge and Dr. Zhu Yujie—for their time and guidance. Shuge’s advice has been especially helpful in the development of my thesis. Her honest critiques and insightful suggestions demonstrated how to conduct conscientious scholarship. I would also like to extend my thanks to friends and colleagues who helped me with my research in various ways. Special thanks to Dr. Caroline Stevenson for her great proof reading skills and Dr. Paul Farrelly for his time in checking the revised parts of my thesis. -

OCTOBER, 1967 Copied from an Original at the History Center

Copied from an original at The History Center. www.TheHistoryCenterOnline.com 2013:023 OCTOBER, 1967 Copied from an original at The History Center. www.TheHistoryCenterOnline.com 2013:023 rom the PRESIDENT'S DESK ... Fellow Employees: There is a certain quality in some people which makes them a good team member whether it be at play or in th e workshop. This quality is usually inherent in a Winner. In a football game, th e coach would call it " team spirit." On the school campus, th e student or professor refers to it as "school pride." Jn th e armed services, the soldier or sailor expresses it as a phrase called "esprit de Corps." But in this work-a-day world, it is merely called " loyalty." On the wall in Mutt Barr's office is a plaque containing these famous words by Elbert Hubbard: "If you work for a man, in heaven's name work for him; Speak well of him and stand by the institution he represents. Remember, an ounce of loyalty is worth a pound of clever- ness. If you must growl, condemn and enternally find fault, why re ign your position. And when you are outside, damn to your heart's content But as long as you are part of the institution do not con demn it. If you do, the first high wind that comes along will blow you away and probably yo u will never know why." I don't believe there is another quality more important to the success of an organization than the loyalty of its employees. -

Hong Kong Walkability Analysis IQP Project Proposal

Hong Kong Walkability Analysis IQP Project Proposal Sponsoring Agencies: Designing Hong Kong and Harbour Business Forum Submitted to: Project Advisor: Zhikun Hou, WPI Professor Project Co‐advisor: Robert Kinicki, WPI Professor On‐Site Liaison: Paul Zimmerman, Designing Hong Kong On‐Site Co‐Liaison: Dr. Sujata S. Govada, Harbour Business Forum Submitted by: Michael Audi Kathryn Byorkman Alison Couture Suzanne Najem Date Submitted: 15 December 2010 Creighton Peet ID 2050 Instructor Table of Contents Title Page .............................................................................................................................................. i Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. ii Table of Figures .................................................................................................................................. iv Table of Tables ..................................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ vi 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Background .................................................................................................................................... 4 -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

I Want to Be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition

Volume 6 Issue 1 2020 “I Want to be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition Charlene Peishan Chan [email protected] ISSN: 2057-1720 doi: 10.2218/ls.v6i1.2020.4398 This paper is available at: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/lifespansstyles Hosted by The University of Edinburgh Journal Hosting Service: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/ “I Want to be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition Charlene Peishan Chan The years leading up to the political handover of Hong Kong to Mainland China surfaced issues regarding national identification and intergroup relations. These issues manifested in Hong Kong films of the time in the form of film characters’ language ideologies. An analysis of six films reveals three themes: (1) the assumption of mutual intelligibility between Cantonese and Putonghua, (2) the importance of English towards one’s Hong Kong identity, and (3) the expectation that Mainland immigrants use Cantonese as their primary language of communication in Hong Kong. The recurrence of these findings indicates their prevalence amongst native Hongkongers, even in a post-handover context. 1 Introduction The handover of Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1997 marked the end of 155 years of British colonial rule. Within this socio-political landscape came questions of identification and intergroup relations, both amongst native Hongkongers and Mainland Chinese (Tong et al. 1999, Brewer 1999). These manifest in the attitudes and ideologies that native Hongkongers have towards the three most widely used languages in Hong Kong: Cantonese, English, and Putonghua (a standard variety of Mandarin promoted in Mainland China by the Government). -

In Hong Kong the Political Economy of the Asia Pacific

The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific Fujio Mizuoka Contrived Laissez- Faireism The Politico-Economic Structure of British Colonialism in Hong Kong The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific Series editor Vinod K. Aggarwal More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/7840 Fujio Mizuoka Contrived Laissez-Faireism The Politico-Economic Structure of British Colonialism in Hong Kong Fujio Mizuoka Professor Emeritus Hitotsubashi University Kunitachi, Tokyo, Japan ISSN 1866-6507 ISSN 1866-6515 (electronic) The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific ISBN 978-3-319-69792-5 ISBN 978-3-319-69793-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69793-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017956132 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Review of Geopolitics and Film Censorship in Cold War Hong Kong (Book Review)

Conflict, Justice, Decolonization: Critical Studies of Inter-Asian Society (2019) 2709-5479 Hong Kong in the Cultural Cold War and the Colonial Southeast Asia: Review of Geopolitics and Film Censorship in Cold War Hong Kong (Book Review) Ip Po-Yee Institute of Social Research and Cultural Studies National Chiao Tung University This article is a review of Zardas Shuk-man Lee’s recently published book Geopolitics and Film Censorship in Cold War Hong Kong (2019), an extensive historical research regarding the institution of film censorship in Hong Kong during the 1940s-1970s. From the perspective of film censorship studies, Lee’s ambitious work questions the Cold War geopolitics and further contributes to cultural Cold War studies, Hong Kong colonial studies and Sinophone studies. Keywords: Cold War, Hong Kong, Sinophone, Colonial studies, Film censorship Over the past two decades, Cold War studies have been faced with a cultural turn. In lieu of the emphasis on political economy or diplomacy of the superpowers, researchers have begun to underscore the localized dimension of state propaganda and cultural production as well. Hong Kong has been commonly regarded as “Berlin of the East” during the Cold War era, an ideological battlefield highly contested by the Chinese Communist Party and the Taiwan Kuomintang – namely “the Left” and “the Right”. While extensive research regarding Hong Kong media and film production has been conducted, rarely has scholarly literature investigated Hong Kong film censorship. As one of the pioneering published research projects, historian Zardas Shuk-man Lee’s new book – translated from her previous thesis – Geopolitics and Film Censorship in Cold War Hong Kong( Chinese title:《冷戰光影:地緣政治下的香港電影審查史》) offers crucial insights about film censorship studies, the cultural Cold War, Hong Kong colonial studies and Sinophone studies. -

Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism

Emory International Law Review Volume 35 Issue 1 2021 Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism Shucheng Wang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Shucheng Wang, Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism, 35 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 21 (2021). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol35/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WANG_2.9.21 2/10/2021 1:03 PM HONG KONG’S CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE UNDER CHINA’S AUTHORITARIANISM Shucheng Wang∗ ABSTRACT Acts of civil disobedience have significantly impacted Hong Kong’s liberal constitutional order, existing as it does under China’s authoritarian governance. Existing theories of civil disobedience have primarily paid attention to the situations of liberal democracies but find it difficult to explain the unique case of the semi-democracy of Hong Kong. Based on a descriptive analysis of the practice of civil disobedience in Hong Kong, taking the Occupy Central Movement (OCM) of 2014 and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (Anti-ELAB) movement of 2019 as examples, this Article explores the extent to which and how civil disobedience can be justified in Hong Kong’s rule of law- based order under China’s authoritarian system, and further aims to develop a conditional theory of civil disobedience for Hong Kong that goes beyond traditional liberal accounts.