July-Sept 2015 Pdf.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Powered by Toursoft

Exotic Himachal-Do not change-Copy1 8 Days/7 Nights Powered by TourSoft Key Attractions Top 15 Places To Visit In Himachal Pradesh If you like anything and everything about snow, you may be inspired by the meaning of the word Himachal. ‘The land of snows’, the meaning, is adequate to give you an idea of what to expect here. Himachal Pradesh is located in the western Himalayas. Surrounded by majestic mountains, out of which some still challenge mankind to conquer them, the beauty of the land is beyond imagination. Simla, one of the most captivating hill stations, is the capital of the state. Given below are the top 15 places to visit in Himachal Pradesh. 1. Kullu Image credit – Balaji.B, CC BY 2.0 Kullu in Himachal Pradesh is one of the most frequented tourist destinations. Often heard along with the name Manali, yet another famous tourist spot, Kullu is situated on the banks of Beas River. It was earlier called as Kulanthpitha, meaning ‘The end of the habitable world’. Awe-inspiring, right? Kullu valley is also known as the ‘Valley of Gods’. Here are some leading destinations in the magical land. - Basheshwar Mahadev Temple - Sultanpur Palace - Parvati Valley - Raison - Raghunathji Temple - Bijli Mahadev Temple - Shoja - Karrain Bathad - Jagatsukh The attractions in Kullu are more. Trekking, mountaineering, angling, skiing, white water rafting and para gliding are some of the adventurous sports available here. 2. Manali Image credit – Balaji.B, CC BY 2.0 Located at an altitude of 6726 feet, Manali offers splendid views of the snow-capped mountains. -

Important Lakes in India

Important Lakes in India Andhra Pradesh Jammu and Kashmir Kolleru Lake Dal Lake Pulicat Lake - The second largest Manasbal Lake brackish – water lake or lagoon in India Mansar Lake Pangong Tso Assam Sheshnag Lake Chandubi Lake Tso Moriri Deepor Beel Wular Lake Haflong Lake Anchar Lake Son Beel Karnataka Bihar Bellandur Lake Kanwar Lake - Asia's largest freshwater Ulsoor lake oxbow lake Pampa Sarovar Karanji Lake Chandigarh Kerala Sukhna Lake Ashtamudi Lake Gujarat Kuttanad Lake Vellayani Lake Hamirsar Lake Vembanad Kayal - Longest Lake in India Kankaria Sasthamcotta Lake Nal Sarovar Narayan Sarovar Madhya Pradesh Thol Lake Vastrapur Lake Bhojtal Himachal Pradesh www.OnlineStudyPoints.comMaharashtra Brighu Lake Gorewada Lake Chandra Taal Khindsi Lake Dashair and Dhankar Lake Lonar Lake - Created by Metoer Impact Kareri and Kumarwah lake Meghalaya Khajjiar Lake Lama Dal and Chander Naun Umiam lake Macchial Lake Manipur Haryana Loktak lake Blue Bird Lake Brahma Sarovar Mizoram Tilyar Lake Palak dïl Karna Lake www.OnlineStudyPoints.com Odisha Naukuchiatal Chilika Lake - It is the largest coastal West Bengal lagoon in India and the second largest Sumendu lake in Mirik lagoon in the world. Kanjia Lake Anshupa Lake Rajasthan Dhebar Lake - Asia's second-largest artificial lake. Man Sagar Lake Nakki Lake Pushkar Lake Sambhar Salt Lake - India's largest inland salt lake. Lake Pichola Sikkim Gurudongmar Lake - One of the highest lakes in the world, located at an altitude of 17,800 ft (5,430 m). Khecheopalri Lake Lake Tsongmo Tso Lhamo Lake - 14th highest lake in the world, located at an altitude of 5,330 m (17,490 ft). -

State of Environment Report Himachal Pradesh

State of Environment Report Himachal Pradesh Department of Environment, Science & Technology Government of Himachal Pradesh Narayan Villa, Shimla-171 002, H.P. Phone No. 0177-2627608, 2627604, 2620559 Website: www.himachal.nic.in/environment State of the Environment Report on Himachal Pradesh © Department of Environment, Science & Technology, Government of Himachal Pradesh. Published by : Department of Environment, Science & Technology, Government of Himachal Pradesh. Narayan Villa, Shimla-171002 (Himachal Pradesh). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the copyright owner. Editing, Typesetting and Printing : Shiva Offset Press, Dehradun - 248 001 Tel.: +91-135-2715748 Fax : 91-135-2715107 E-mail: [email protected] ii iii iv JAGAT PRAKASH NADDA Minister (Forests, Science & Technology) Himachal Pradesh MESSAGE It gives me immense pleasure to learn that the Department of Environment, Science & Technology, Government of Himachal Pradesh is bringing out the second State of Environment Report for the State. I have been given to understand that the State of Environment Report being published by the Department would display vital information on the environment related aspects of the State. As a Minister in-charge of the Department it shall be my endeavour to equip the Department in such a way that it successfully carries forward the protection, prevention and conservation agenda in a most sustainable manner. Himachal Pradesh, which has its own peculiar environmental problems, needs to tread the devel- opmental path without compromising with its pristine environment. -

Initial Environmental Examination IND:Himachal Pradesh Skills

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 49108-002 June 2019 IND: Himachal Pradesh Skills Development Project Package : Rural Livelihood Center at Garola Panchayat, Bharmour, Chamba District (Himachal Pradesh) Submitted by: Government of Himachal Pradesh This initial environment examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 49108-002 April 2019 India: Himachal Pradesh Skill Development Project Name of the subproject: Rural Livelihood Center at Garola Panchayat, Bharmour, Chamba District (Himachal Pradesh) Prepared by the Government of Himachal Pradesh for the Asian Development Bank This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as -

IND:Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy Transmission Investment Program

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 43464-026 June 2020 IND: Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy Transmission Investment Program - Tranche 2 Submitted by: HP Power Transmission Corporation Limited (HPPTCL) This initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. This report is an updated version of the IEE report posted in May 2018 available on adb.org/projects/documents/ind-43464-026-iee. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Recd. 9.06.20 SFG Log: 4181 Initial EnvironmentalExamination Project Number: 43464-026-IND June 2020 India: Himachal PradeshCleanEnergy Transmission InvestmentProgramme Loan 3001-IND (Tranche – 2) Prepared by HP Power Transmission Corporation Limited (HPPTCL) The initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary innature. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 1 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... -

General-STATIC-BOLT.Pdf

oliveboard Static General Static Facts CLICK HERE TO PREPARE FOR IBPS, SSC, SBI, RAILWAYS & RBI EXAMS IN ONE PLACE Bolt is a series of GK Summary ebooks by Oliveboard for quick revision oliveboard.in www.oliveboard.in Table of Contents International Organizations and their Headquarters ................................................................................................. 3 Organizations and Reports .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Heritage Sites in India .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Important Dams in India ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Rivers and Cities On their Banks In India .................................................................................................................. 10 Important Awards and their Fields ............................................................................................................................ 12 List of Important Ports in India .................................................................................................................................. 12 List of Important Airports in India ............................................................................................................................. 13 List of Important -

GAYATRI's I N S T I T U T E 1St Puliya C.H.B, Main Chopasni Road, Jodhpur. 9119119781 Page 1

Number Square Cube Square Root Cubic Root Number Square Cube Square Root Cubic Root x2 x3 x1/2 x1/3 x2 x3 x1/2 x1/3 1 1 1 1.000 1.000 61 3721 226981 7.810 3.936 2 4 8 1.414 1.260 62 3844 238328 7.874 3.958 3 9 27 1.732 1.442 63 3969 250047 7.937 3.979 4 16 64 2.000 1.587 64 4096 262144 8.000 4.000 5 25 125 2.236 1.710 65 4225 274625 8.062 4.021 6 36 216 2.449 1.817 66 4356 287496 8.124 4.041 7 49 343 2.646 1.913 67 4489 300763 8.185 4.062 8 64 512 2.828 2.000 68 4624 314432 8.246 4.082 9 81 729 3.000 2.080 69 4761 328509 8.307 4.102 10 100 1000 3.162 2.154 70 4900 343000 8.367 4.121 11 121 1331 3.317 2.224 71 5041 357911 8.426 4.141 12 144 1728 3.464 2.289 72 5184 373248 8.485 4.160 13 169 2197 3.606 2.351 73 5329 389017 8.544 4.179 14 196 2744 3.742 2.410 74 5476 405224 8.602 4.198 15 225 3375 3.873 2.466 75 5625 421875 8.660 4.217 16 256 4096 4.000 2.520 76 5776 438976 8.718 4.236 17 289 4913 4.123 2.571 77 5929 456533 8.775 4.254 18 324 5832 4.243 2.621 78 6084 474552 8.832 4.273 19 361 6859 4.359 2.668 79 6241 493039 8.888 4.291 20 400 8000 4.472 2.714 80 6400 512000 8.944 4.309 21 441 9261 4.583 2.759 81 6561 531441 9.000 4.327 22 484 10648 4.690 2.802 82 6724 551368 9.055 4.344 23 529 12167 4.796 2.844 83 6889 571787 9.110 4.362 24 576 13824 4.899 2.884 84 7056 592704 9.165 4.380 25 625 15625 5.000 2.924 85 7225 614125 9.220 4.397 26 676 17576 5.099 2.962 86 7396 636056 9.274 4.414 27 729 19683 5.196 3.000 87 7569 658503 9.327 4.431 28 784 21952 5.292 3.037 88 7744 681472 9.381 4.448 29 841 24389 5.385 3.072 89 7921 704969 9.434 -

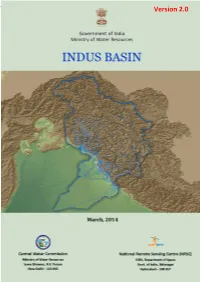

Purpose of Hydroelectric Generation.Only 13 Dams Are Used for Flood Control in the Basin and 19 Dams Are Used for Irrigation Along with Other Usage

Indus (Up to border) Basin Version 2.0 www.india-wris.nrsc.gov.in 1 Indus (Up to border) Basin Preface Optimal management of water resources is the necessity of time in the wake of development and growing need of population of India. The National Water Policy of India (2002) recognizes that development and management of water resources need to be governed by national perspectives in order to develop and conserve the scarce water resources in an integrated and environmentally sound basis. The policy emphasizes the need for effective management of water resources by intensifying research efforts in use of remote sensing technology and developing an information system. In this reference a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed on December 3, 2008 between the Central Water Commission (CWC) and National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) to execute the project “Generation of Database and Implementation of Web enabled Water resources Information System in the Country” short named as India-WRIS WebGIS. India-WRIS WebGIS has been developed and is in public domain since December 2010 (www.india- wris.nrsc.gov.in). It provides a ‘Single Window solution’ for all water resources data and information in a standardized national GIS framework and allow users to search, access, visualize, understand and analyze comprehensive and contextual water resources data and information for planning, development and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). Basin is recognized as the ideal and practical unit of water resources management because it allows the holistic understanding of upstream-downstream hydrological interactions and solutions for management for all competing sectors of water demand. -

No. Name of Student Enrolment No

A Global Country Study Report On AUTOMOBILE INDUSRTY IN CAMBODIA & Business Opportunities for Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh Submitted to Institute Code: 735 N.R. Institute of Business Management Ahmedabad In partial Fulfillment of the Requirement of the award for the degree of Master of Business Administration (MBA) Under the Guidance of Prof. Isha Dave No. Name of Student Enrolment No. 1. Tushal Hareja 147350592043 2. Ashik Khokhar 147350592065 3. Vishal Mehta 147350592085 4. Paresh Rathod 147350592131 5. Vinay Shah 147350592151 6. Mihir Tanna 147350592160 Offered By Gujarat Technological University Ahmedabad 1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e 3 | P a g e PLAGIARISM REPORT 4 | P a g e TABLE OF CONTENT SR.NO. PARTICULARS PAGE NO. 1. Introduction to Cambodia 06 2. Introduction to Himachal Pradesh 24 3. Introduction to Gujarat 32 4. Justification for selection of automobile industry 45 5. Steepled analysis between Cambodia & Gujarat 47 6. Swot analysis of Cambodia 68 7. Swot analysis of Gujarat 74 8. Swot analysis of Himachal Pradesh 77 9. Bilateral trade opportunity between Cambodia & Gujarat 81 5 | P a g e CHAPTER- 1 About the Country Cambodia 6 | P a g e INTRODUCTION OF CAMBODIA History of Cambodia The history of Cambodia, a century in mainland South-east Asia, can be found back to at least the 5th millennium BC. Detailed records of a political framework on territory, what is now modern day Cambodia first part in Chinese annals in reference to Funan, a policy that encompassed the southern part of the Indochinese peninsula during the 1st to 6th centuries. -

Model Career Center at Chamba Initial Environmental Examination

Initial Environmental Examination April 2021 India: Himachal Pradesh Skills Development Project Package : Model Career Center at Chamba Prepared by Government of Himachal Pradesh for the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Recd. on 19.4.21 SFG Log: 4604 Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 49108-002 April 2021 India: Himachal Pradesh Skill Development Project Sub-project– Model Career Center at Chamba Prepared by the Government of Himachal Pradesh for the Asian Development Bank This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other -

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach and Studies Analyzing Resource Potential for Nature Based Tourism

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach and Studies ISSN NO:: 2348 – 537X Analyzing Resource Potential for Nature Based Tourism: A Case Study of the State of Himachal Pradesh (India) Punit Gautam Associate Professor, Department of Tourism and Hotel Management, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya (India) ―Potential‖ broadly insinuates something promising but not yet (fully) exploited; it symbolizes the sum total of qualitative and quantitative values of the given resources on which the degree and extent of its exploitability depends (Kandari, 1984). In the context of tourism, assessing the resource potential in quantitative terms is highly complex process, if not impossible, as it involves the physical, psychological and spiritual demands on the people belonging to diverse geographical, socio-cultural and economic backgrounds who travel under different motives, interests, preferences and immediate needs. To quote Kandari (1984), ―potential for tourism development in any area depends on the availability of recreational resources in addition to the factors like climate, seasons, accessibility, proximity to market, political stability, state of economy and general infrastructure, quality of natural environment, attitude of the local people, travel trade entrepreneurs and tourism planners, the existing tourist plant facilities and the degree to which they can be further developed within the prevailing limitations of natural, cultural and financial environments. Healthy combination of all those and many other factors -

Statewise Static GK Gr8ambitionz.Com National Parks

Statewise Static GK Gr8AmbitionZ.com National Parks State National Park Guru Ghasi Das Kalesar National Park (Sanjay) National Andhra Pradesh Kaziranga National Sultanpur National Park Park Park Papikonda National Goa Park Manas National Park Himachal Pradesh Bhagwan Mahavir Sri Venkateswara Nameri National Park Pin Valley National (Mollem) National National Park Park Rajiv Gandhi Orang Park Rajiv Gandhi National National Park Great Himalayan Gujarat Park National Park Bihar Blackbuck National Arunachal Pradesh Inderkilla National Valmiki National Park Park, Velavadar Park Namdapha National Chhattisgarh Gir Forest National Park Khirganga National Park Indravati National Park Mouling National Park Marine National Park, Park Simbalbara National Gulf of Kutch Kanger Valley Park Assam National Park Bansda National Park Jammu and Kashmir Dibru-Saikhowa Haryana Statewise Static GK Gr8AmbitionZ.com Dachigam National Anshi national park Madhav National Park Manipur Park Kerala Mandla Plant Fossils Keibul Lamjao NP Hemis National Park NP Eravikulam National Meghalaya Kishtwar National Park Panna National Park Balphakram National Park Mathikettan Shola Pench National Park Park Salim Ali NationaPark National Park Sanjay National Park Meghalaya Jharkhand Periyar National Park Satpura National Park Nokrek National Park Betla National Park Silent Valley National Van Vihar NP Mizoram Park Karnataka Maharashtra Murlen National Park Anamudi Shola Bandipur National National Park Chandoli NP Park Phawngpui Blue Pampadum Shola Gugamal NP Mountain NP Bannerghatta