Specters of War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AM Mike Nichols Production Bios FINAL

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #AmericanMasters Mike Nichols: American Masters Premieres nationwide Friday, January 29 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) Production Biographies Elaine May Director Elaine May began in Second City where she formed a successful comedy team with Mike Nichols. She earned a Drama Desk Award for her play Adaptation ; wrote, directed and performed in A New Leaf ; directed The Heartbreak Kid (the original); wrote and directed Mikey & Nicky and Ishtar ; received an Oscar nomination for writing Heaven Can Wait ; reunited with Nichols to write The Birdcage and Primary Colors (a BAFTA-winner); and worked with producer Julian Schlossberg on six New York productions. She has done other things, but this is enough. Julian Schlossberg Producer Julian Schlossberg is an award-winning theater, film and television producer. For TV, he’s produced for HBO, AMC and PBS, including American Masters — Nichols & May: Take Two and American Masters: The Lives of Lillian Hellman . Plays produced by Schlossberg have earned many honors, including six Tony Awards, two Obie Awards, seven Drama Desk Awards and five Outer Critics Circle Awards, among them Bullets Over Broadway: The Musical , The Beauty Queen of Leenane and Fortune’s Fool . He also produced six of Elaine May’s plays: Relatively Speaking , Adult Entertainment , After the Night and the Music , Power Plays , Death Defying Acts and Taller Than a Dwarf . -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

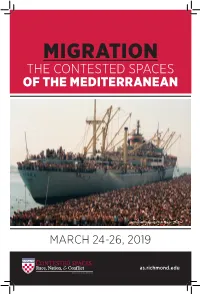

Migration the Contested Spaces of the Mediterranean

MIGRATION THE CONTESTED SPACES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN FOTOREPORTER LUCA TURI -BARI- ITALY MARCH 24-26, 2019 as.richmond.edu Naples, Italy - May 18, 2015: High Seas Patrol Boat Comandante Bettica filled with refugees o the Amalfi Coast. PHOTO: DEBORAHMAXEMOW/ISTOCKPHOTO THE YEAR 2019 MARKS THE 30TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL: THE HISTORICAL EVENT THAT DRAMATICALLY CHANGED THE POLITICAL, SOCIAL, AND CULTURAL FACE OF EUROPE. After the Wall came down, thousands This conference aims to address of people from Eastern communist the immigrant experience in the countries crossed into Western Mediterranean from dierent Europe by land and sea, transforming perspectives. What are the and reshaping the places that oered motivations or obligations that them asylum or refuge. In more push people to leave their country recent years, political instability of origin? What are the struggles in some Middle-Eastern and sub- they face in their journeys and Saharan countries has increased the the diculties that they meet influx of migrants and refugees in the when they arrive in a new space? closest ports of entry, notably Greece Through lectures, conferences, films, and Italy, raising numerous questions interviews, and discussions with about how and whether to manage experts from diverse backgrounds the resettlement of these populations we want to illustrate the complexity across Europe. The humanitarian of these issues. crisis such population influx has brought about has created mixed reactions. On the one hand, people All sessions will take place in the have responded with great empathy, Carole Weinstein International but on the other, it has opened the Center Commons. -

Hits of the Week

NEWSPAPER ISSN 0034 1C22 L Au.:77,2,1980,2.50 Hits of the Week SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS ELECTRIC LIGHTORCHESTRA,"ALL ROXY MUSIC, "OVER YOU" (prod.by DIONNE WARWICK, "NO NIGHT SO OVER THE WORLD" (prod. by group -Davies) (writers: Ferry- LONG." Her platinum success last MCA Lynne) (writer: Lynne) (Jet/Un- Manzanera)(E.G.,BMI)(3:24). time around demonstrated that this RE CORDS art,BMI) (4:04). A spirited chor- "I'm so lost in love-over you."lady's voice is pure magic on the us, triumphant keyboards & mul- Said so often but seldom as ef- airwaves. With the impeccable pro- titudinous handclaps carrythe fectively ason thismarvelous duction of Steve Buckingham, she joyous, uplifting message on this Ferry-Manzaneracutfromthe can do it again with the title track blockbuster from the "Xanadu" "Flesh & Blood" LP. A smashand the heavenly "How You Once soundtrack. MCA 41289. across-the-board. Atco 7301. Loved Me." Arista AL 9526 (8.98). BILLY JOEL, "DON'T ASK ME WHY" (prod. STEPHANIE MILLS, "NEVER KNEW LOVE GEORGE BENSON, "GIVE ME THE by Ramone) (writer:Joel)(Im- LIKE THIS BEFORE" (prod. byNIGHT." One of the few earthlings pulsive/April, ASCAP) (2:56). Mtume-Lucas)(writers:Mtume- blessedwithextraordinaryvocal Joel'sfirsttwohitsfromthe Lucas)(FrozenButterfly,BMI) and instrumental talents, Benson is phenomenal "Glass Houses" LP (3:29). Glistening keyboards, an tearing up the charts with the title were unabashed rockers. Here's angelic chorus & Mills'lovely single from this LP. Quincy Jones' one of his easy rollin' romantic vocaltranslateintoafairytale productionsorceryis consistent piano ballads that often become qualitywith amatching hook. -

Brooklyn Academy of Music Harvey Theater 651 Fulton Street, Brooklyn, NY from the CO-FOUNDERS

Brooklyn Academy of Music Harvey Theater 651 Fulton Street, Brooklyn, NY FROM THE CO-FOUNDERS Dear Friends, Two months, countless hours, goofiness, insane drama, ten thousand emails from strangers (most of which were kind), volunteers who helped beyond the call, others who offered and then bagged , GALLONS of chai latte, huge dreams, joyfully freezing with 500,000 others, a miracle a day, maxed out credit cards, 11th hour angels, getting flayed on right wing radio and adored on NPR, articles in papers big and small, and the infamous phone interview with Newsweek from our "office"-the Times Square Popeye's Fried Chicken. And here we are, over 820 readings in 52 countries, and in all 50 American States (North Dakota making a fashionably late entrance) . We come to this, our day of action, happy that Lysistrata Project can contribute to the global ruckus being raised against the war and satisfied we've done our best to let the world know that President Bush does not speak for all Americans. Most of all, though, we're honored to be joined by you, this fine cast and crew, and so many new friends around the world - from the jungles of Hawaii to the jungles of Cambodia, from living rooms in Syria and Iowa, and secret readings in China and Jerusa lem to all-out theatrical takeovers of Chicago, Paris, Baltimore, Minneapolis, London and Los Ange les. But most of all, we're thrilled that hundreds of people have become activists for the first time with this project, and will never be silent again. -

Listeréalisateurs

A Crossing the bridge : the sound of Istanbul (id.) 7-12 De lʼautre côté (Auf der anderen Seite) 14-14 DANIEL VON AARBURG voir sous VON New York, I love you (id.) 10-14 DOUGLAS AARNIOKOSKI Sibel, mon amour - head-on (Gegen die Wand) 16-16 Highlander : endgame (id.) 14-14 Soul kitchen (id.) 12-14 PAUL AARON MOUSTAPHA AKKAD Maxie 14 Le lion du désert (Lion of the desert) 16 DODO ABASHIDZE FEO ALADAG La légende de la forteresse de Souram Lʼétrangère (Die Fremde) 12-14 (Ambavi Suramis tsikhitsa - Legenda o Suramskoi kreposti) 12 MIGUEL ALBALADEJO SAMIR ABDALLAH Cachorro 16-16 Écrivains des frontières - Un voyage en Palestine(s) 16-16 ALAN ALDA MOSHEN ABDOLVAHAB Les quatre saisons (The four seasons) 16 Mainline (Khoon Bazi) 16-16 Sweet liberty (id.) 10 ERNEST ABDYJAPOROV PHIL ALDEN ROBINSON voir sous ROBINSON Pure coolness - Pure froideur (Boz salkyn) 16-16 ROBERT ALDRICH Saratan (id.) 10-14 Deux filles au tapis (The California Dolls - ... All the marbles) 14 DOMINIQUE ABEL TOMÁS GUTIÉRREZ ALEA voir sous GUTIÉRREZ La fée 7-10 Rumba 7-14 PATRICK ALESSANDRIN 15 août 12-16 TONY ABOYANTZ Banlieue 13 - Ultimatum 14-14 Le gendarme et les gendarmettes 10 Mauvais esprit 12-14 JIM ABRAHAMS DANIEL ALFREDSON Hot shots ! (id.) 10 Millenium 2 - La fille qui rêvait dʼun bidon dʼessence Hot shots ! 2 (Hot shots ! Part deux) 12 et dʼune allumette (Flickan som lekte med elden) 16-16 Le prince de Sicile (Jane Austenʼs mafia ! - Mafia) 12-16 Millenium 3 - La reine dans le palais des courants dʼair (Luftslottet som sprangdes) 16-16 Top secret ! (id.) 12 Y a-t-il quelquʼun pour tuer ma femme ? (Ruthless people) 14 TOMAS ALFREDSON Y a-t-il un pilote dans lʼavion ? (Airplane ! - Flying high) 12 La taupe (Tinker tailor soldier spy) 14-14 FABIENNE ABRAMOVICH JAMES ALGAR Liens de sang 7-14 Fantasia 2000 (id. -

Video Catalogue Eric Roberts October 28, 2004

Video Catalogue Eric Roberts October 28, 2004 AN ACT OF CONSCIENCE, Robbie Leppzer,1997, 1:30. This film follows the history of Randy Kehler and Betsy Corner,two tax resisters from Colrain, Massachusetts. After years of refusing to pay war taxes, the Federal Government seized their home and sold it to pay the arrears. The film chronicles the campaign of nonviolent resistance to save their home but also explores the class and political conflicts that arise between the resisters and the family that buys the home. THE ADVENTURES OF PRISCILLA: QUEEN OF THE DESERT, Stephen Elliot, 1994, 1:42. The story line of the film involves a group of three drag performers from the Sydneygay nighclubs who drive their lavender bus, Priscilla, across the desert to perform in Alice Springs. The fun comes from the energy that the trio and supporting cast bring to the adventure, which ends up being a wonderfully funnyand life-affirming tale. AGAINST THE CURRENT,Dmitri Delov, The Glasnost Film Festival, 1988, 0:27. ‘‘This is a film about ecological crime. Despite being labeled extremists, the residents of Kirishi protest a major syn- thetic protein plant. ‘Wecouldn’tbreathe, we coughed, we buried our children . .. but we couldn’tput up with it anymore,’ayoung woman shouts indignantly at a rally.’’[from the film notes] ALICE’S RESTAURANT,Arthur Penn, 1969, 1:51. At one level, this is the story told by Arlo Guthrie’ssong, with the half-a-ton of garbage, the twenty-seven8x10 col- ored glossy photographs, and the draft induction center where you get injected, inspected, detected, infected, neglected, and selected. -

In – Differenza

Bologna e Forlì, 27 marzo - 5 aprile ‘09 in – differenza 9th international arts and film festival cinema dei diritti umani arte musica workshops www.humanrightsnights.org info: 051 2194808 / 2195311 Human Rights Nights 2009 Promosso da / Supported by Comune di Bologna Cineteca Bologna Alma Mater Studiorum-Università di Bologna Assemblea Legislativa Regione Emilia-Romagna Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio in Bologna Center for Constitutional Studies and Democratic Development Comitato Direttivo / Board of Directors Michela Dalla Vite, Gian Luca Farinelli, Justin Frosini, Roberto Grandi, Giulia Grassilli, Andrea Morini, Benedetto Zacchiroli, Paolo Zurla Human Rights Nights 2009 In collaborazione con / In collaboration with Unibocultura, Polo Scientifico-Didattico di Forlì, Collegio Superiore, Facoltà di Agraria, Facoltà di Scienze della Formazione, Facoltà di Economia – Forlì, Facoltà di Scienze Politiche “R. Ruffilli”, SSLMIT – Scuola Superiore di Lingue Moderne per Interpreti e Traduttori-Forlì, Dipartimento delle Arti Visive, Dipartimento di Chimica “Giaco- mo Ciamician”, Dipartimento di Discipline della Comunicazione, Dipartimento di Musica e Spettacolo, Diparti- mento di Scienze Giuridiche «Antonio Cicu», Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Educazione “Giovanni Maria Bertin”, Italian Society for Law and Literature-ISLL, Alma Jazz Orchestra Comune di Forlì, Fondo per la Cultura, Romagna Acque, Aegee, Cactus, Koinè, UDU Accademia di Belle Arti, AfricanBamba, Amnesty International, Aven Amenza – Associazione Rumeni di Bologna, BIM Distribuzione, -

Bamcinématek and Actnow Arts Present the Seventh Annual New Voices in Black Cinema, April 26–30

BAMcinématek and ActNow Arts present the seventh annual New Voices in Black Cinema, April 26–30 This year’s line-up features three New York premieres and Sundance favorite Quest. The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. March 31, 2017/Brooklyn, NY—From Wednesday, April 26 through Sunday, April 30, BAMcinématek presents the seventh New Voices in Black Cinema festival. Reflecting the wide spectrum of views and themes within African diaspora communities in the United States and beyond, the series includes nine feature length films and two shorts programs. New Voices in Black Cinema, one of a variety of ActNow programs presented in partnership with BAMcinématek since 2009, provides a showcase for new and established voices in black independent cinema. The series begins on Wednesday, April 26 with Burning Sands (2017—April 26), the feature filmmaking debut of Gerard McMurray. The film follows a freshman fraternity pledge’s descent into the violence of underground hazing. 9 Rides (2016—Apr 26 & 29), the first feature to be shot entirely on an iPhone 6, is the second feature by director Matthew A. Cherry, and follows an Uber driver as he traverses Los Angeles on the busiest night of the year. Steps (2016—Apr 27), by co-directors Rock Davis and Jay Rodriguez Jr., becomes a story about forgiveness when a man working as a home health worker is assigned to care for the gang member who shot him years before. On Apr 29 and 30 we also feature two shorts programs. Looking outside of the United States, director Jean-Claude Flamand-Barny’s Gangs of the French Caribbean (2016—Apr 28 & 30) is set in 1970s France. -

May June 2014

ELINOR BUNIN MUNROE FILM CENTER 144 W 65th St. | WALTER READE THEATER 165 W 65th St. | New York, NY 10023 | FilmLinc.com FASSBINDER: ROMANTIC ANARCHIST (PART 1) The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant MAY JUNE 2014 Columbia University Film Festival May 2 — 6 | New York African Film Festival May 7 — 13 | Fassbinder: Romantic Anarchist (Part 1) May 16 — June 1 | Open Roads: New Italian Cinema June 5 — 12 | Human Rights Watch Film Festival June 13 — 22 | Film Comment Double Feature June 25 | New York Asian Film Festival June 27 — July 10 MAY 2014 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 3 Follow us on Visit FilmLinc.com 7:00 CUFF Program A 2:00 CUFF Program C for more information 9:00 CUFF Program B 4:00 CUFF Program D 7:00 CUFF Program E 9:00 CUFF Program F VISIT FILMLINC.COM FOR TICKETS AND VENUE | IN-PERSON APPEARANCES 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2:00 Frozen 6:30 From Screen to Stage: 12:55 Met Opera Encore: 2:00 Mugabe: Villain or Hero? 2:00 New African Shorts 2:00 Ninah’s Dowry 12:55 Met Opera: 5:00 CUFF Program G Bullets Over Broadway Così fan tutte 4:30 Winter of Discontent + 4:30 Aya of Yop City 4:00 Bastards + Beleh La Cenerentola 7:00 CUFF Program H 4:00 Creative Producing Pitch Wooden Hands 6:30 It’s Us 7:00 Half of a Yellow Sun 6:30 Of Good Report Contest 7:00 Film Society Talks: 7:30 Convergence: APP 9:45 Half of a Yellow Sun 9:15 Confusion Na Wa 7:00 PANEL: Is it Television? James Gray (The Free event! Palo Alto OPENS The Rise of Episodic Immigrant) Free event! 8:45 Grigris + Columbite Storytelling 7:30 Confusion Na Wa Tantalite -

J Une 1, 2019

AATI NATIONAL CONFERENCE AT MARIST COLLEGE MAY 31 – JUNE 1, 2019 1 American Association of Teachers of Italian Executive Council President Giuseppe Cavatorta, University of Arizona Vice President (University) Daniela Cavallero, DePaul University Vice President (K-12) Lyn Scolaro, Prospect High School Secretary/Treasurer Enza Antenos, Montclair State University Director of Communication Ryan Calabretta-Sajder, University of Arkansas Past President Salvatore Bancheri, University of Toronto Regional Representatives New England Gina Maiellaro, Northeastern University California Clorinda Donato, California State University, Long Beach New York State Elisabetta D’Amanda, Rochester Institute of Technology Maureen (Marina) Melita, Marist College Mid-Atlantic Daniele DeFeo, Princeton University Southwest-South Federica Santini, Kennesaw State University Midwest Chiara Fabbian, University of Illinois at Chicago Plains-Southwest Antontella Dell’Anna, Arizona State University Rocky Mountains-Far West Chris Picicci, Colorado State University-Pueblo Canada Teresa Lobalsamo, University of Toronto, Mississauga Italy Massimo Vedovelli, Università per Stranieri di Siena 2 Graduate Student Representative Sara Galli, University of Toronto High School Representatives Antonietta Di Pietro, M-DCPS School District (FL) Amelia Fausta Ippoliti, Rio Rancho High School (NM) Patti Grunther, Watchung Regional High School (NJ) Justin Ehrenberg, Bear Creek High School (CA) Danny Monsalve Montilla, Abraham Lincoln High School AATI Ex-Officio Members Michael Lettieri, -

Moma EXHIBITION AUTOMATIC UPDATE EXPLORES THE

MoMA’s NINTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF FILM PRESERVATION SHOWCASES NEWLY RESTORED MASTERWORKS AND REDISCOVERIES Festival Features Films by Roger Corman, Forugh Farrokhzad, George Kuchar, Alberto Lattuada, Louis Malle, Agnes Martin, Georges Méliès, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, Jean Rouch, and Seijun Suzuki Guest presenters include Joe Dante, Walter Hill, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Elaine May, Mario Montez, Thelma Schoonmaker, and Martin Scorsese To Save and Project: The Ninth MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation October 14–November 19, 2011 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, September 20, 2011—The Museum of Modern Art presents To Save and Project: The Ninth MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation, the annual festival of preserved and restored films from archives, studios, and distributors around the world, from October 14 through November 19, 2011. This year’s festival comprises over 35 films from 14 countries, virtually all of them having their New York premieres, and some shown in versions never before seen in the United States. Complementing the annual festival is a retrospective devoted to filmmaker Jack Smith, featuring 11 newly struck prints acquired for MoMA’s collection and introduced on November 13 by Mario Montez, star of Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1962–63) and Normal Love (1963–65). To Save and Project is organized by Joshua Siegel, Associate Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art. Opening this year’s festival is Joe Dante’s digital preservation of The Movie Orgy (1968). Dante, who created some of the best genre-bending movies of the past 40 years, including Piranha, The Howling, Gremlins, and Matinee, will introduce a rare screening of The Movie Orgy on October 14.