Empiricism and Positivism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philosophical Underpinnings of Educational Research

The Philosophical Underpinnings of Educational Research Lindsay Mack Abstract This article traces the underlying theoretical framework of educational research. It outlines the definitions of epistemology, ontology and paradigm and the origins, main tenets, and key thinkers of the 3 paradigms; positivist, interpetivist and critical. By closely analyzing each paradigm, the literature review focuses on the ontological and epistemological assumptions of each paradigm. Finally the author analyzes not only the paradigm’s weakness but also the author’s own construct of reality and knowledge which align with the critical paradigm. Key terms: Paradigm, Ontology, Epistemology, Positivism, Interpretivism The English Language Teaching (ELT) field has moved from an ad hoc field with amateurish research to a much more serious enterprise of professionalism. More teachers are conducting research to not only inform their teaching in the classroom but also to bridge the gap between the external researcher dictating policy and the teacher negotiating that policy with the practical demands of their classroom. I was a layperson, not an educational researcher. Determined to emancipate myself from my layperson identity, I began to analyze the different philosophical underpinnings of each paradigm, reading about the great thinkers’ theories and the evolution of social science research. Through this process I began to examine how I view the world, thus realizing my own construction of knowledge and social reality, which is actually quite loose and chaotic. Most importantly, I realized that I identify most with the critical paradigm assumptions and that my future desired role as an educational researcher is to affect change and challenge dominant social and political discourses in ELT. -

The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: a Personal View1

Weber/Editor’s Comments EDITOR’S COMMENTS The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: A Personal View1 Many years ago I attended a conference on interpretive research in information systems. My goal was to learn more about interpretive research. In my Ph.D. education, I had studied primarily positivist research methods—for example, experiments, surveys, and field studies. I knew little, however, about interpretive methods. I hoped to improve my knowledge of interpretive methods with a view to using them in due course in my research work. A plenary session at the conference was devoted to a panel discussion on improving the acceptance of interpretive methods within the information systems discipline. During the session, a number of speakers criticized positivist research harshly. Many members in the audience also took up the cudgel to denigrate positivist research. If any other positivistic researchers were present at the session beside me, like me they were cowed. None of us dared to rise and speak in defence of positivism. Subsequently, I came to understand better the feelings of frustration and disaffection that many early interpretive researchers in the information systems discipline experienced when they attempted to publish their work. They felt that often their research was evaluated improperly and treated unfairly. They contended that colleagues who lacked knowledge of interpretive research methods controlled most of the journals. As a result, their work was evaluated using criteria attuned to positivism rather than interpretivism. My most-vivid memory of the panel session, however, was my surprise at the way positivism was being characterized by my colleagues in the session. -

Some Thoughts About Natural Law

Some Thoughts About Natural Law Phflip E. Johnsont My first task is to define the subject. When I use the term "natural" law, I am distinguishing the category from other kinds of law such as positive law, divine law, or scientific law. When we discuss positive law, we look to materials like legislation, judicial opinions, and scholarly anal- ysis of these materials. If we speak of divine law, we ask if there are any knowable commands from God. If we look for scientific law, we conduct experiments, or make observations and calculations, in order to come to objectively verifiable knowledge about the material world. Natural law-as I will be using the term in this essay-refers to a method that we employ to judge what the principles of individual moral- ity or positive law ought to be. The natural law philosopher aspires to make these judgments on the basis of reason and human nature without invoking divine revelation or prophetic inspiration. Natural law so defined is a category much broader than any particular theory of natural law. One can believe in the existence of natural law without agreeing with the particular systems of natural law advocates like Aristotle or Aquinas. I am describing a way of thinking, not a particular theory. In the broad sense in which I am using the term, therefore, anyone who attempts to found concepts of justice upon reason and human nature engages in natural law philosophy. Contemporary philosophical systems based on feminism, wealth maximization, neutral conversation, liberal equality, or libertarianism are natural law philosophies. -

Scientific Explanation

Scientific Explanation Michael Strevens For the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy, second edition The three cardinal aims of science are prediction, control, and expla- nation; but the greatest of these is explanation. Also the most inscrutable: prediction aims at truth, and control at happiness, and insofar as we have some independent grasp of these notions, we can evaluate science’s strate- gies of prediction and control from the outside. Explanation, by contrast, aims at scientific understanding, a good intrinsic to science and therefore something that it seems we can only look to science itself to explicate. Philosophers have wondered whether science might be better off aban- doning the pursuit of explanation. Duhem (1954), among others, argued that explanatory knowledge would have to be a kind of knowledge so ex- alted as to be forever beyond the reach of ordinary scientific inquiry: it would have to be knowledge of the essential natures of things, something that neo-Kantians, empiricists, and practical men of science could all agree was neither possible nor perhaps even desirable. Everything changed when Hempel formulated his dn account of ex- planation. In accordance with the observation above, that our only clue to the nature of explanatory knowledge is science’s own explanatory prac- tice, Hempel proposed simply to describe what kind of things scientists ten- dered when they claimed to have an explanation, without asking whether such things were capable of providing “true understanding”. Since Hempel, the philosophy of scientific explanation has proceeded in this humble vein, 1 seeming more like a sociology of scientific practice than an inquiry into a set of transcendent norms. -

Two Concepts of Law of Nature

Prolegomena 12 (2) 2013: 413–442 Two Concepts of Law of Nature BRENDAN SHEA Winona State University, 528 Maceman St. #312, Winona, MN, 59987, USA [email protected] ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE / RECEIVED: 04–12–12 ACCEPTED: 23–06–13 ABSTRACT: I argue that there are at least two concepts of law of nature worthy of philosophical interest: strong law and weak law . Strong laws are the laws in- vestigated by fundamental physics, while weak laws feature prominently in the “special sciences” and in a variety of non-scientific contexts. In the first section, I clarify my methodology, which has to do with arguing about concepts. In the next section, I offer a detailed description of strong laws, which I claim satisfy four criteria: (1) If it is a strong law that L then it also true that L; (2) strong laws would continue to be true, were the world to be different in some physically possible way; (3) strong laws do not depend on context or human interest; (4) strong laws feature in scientific explanations but cannot be scientifically explained. I then spell out some philosophical consequences: (1) is incompatible with Cartwright’s contention that “laws lie” (2) with Lewis’s “best-system” account of laws, and (3) with contextualism about laws. In the final section, I argue that weak laws are distinguished by (approximately) meeting some but not all of these criteria. I provide a preliminary account of the scientific value of weak laws, and argue that they cannot plausibly be understood as ceteris paribus laws. KEY WORDS: Contextualism, counterfactuals, David Lewis, laws of nature, Nancy Cartwright, physical necessity. -

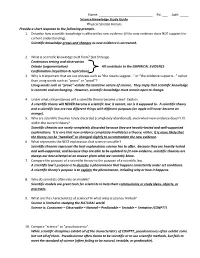

Ast#: ___Science Knowledge Study Guide Physical

Name: ______________________________ Pd: ___ Ast#: _____ Science Knowledge Study Guide Physical Science Honors Provide a short response to the following prompts. 1. Describe how scientific knowledge is affected by new evidence (if the new evidence does NOT support the current understanding). Scientific knowledge grows and changes as new evidence is uncovered. 2. What is scientific knowledge built from? (list 3 things) Continuous testing and observation Debate (argumentation) All contribute to the EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE Confirmation (repetition & replication) 3. Why is it important that we use phrases such as “the results suggest…” or “the evidence supports…” rather than using words such as “prove” or “proof”? Using words such as “prove” violate the tentative nature of science. They imply that scientific knowledge is concrete and unchanging. However, scientific knowledge must remain open to change. 4. Under what circumstances will a scientific theory become a law? Explain. A scientific theory will NEVER become a scientific law; it cannot, nor is it supposed to. A scientific theory and a scientific law are two different things with different purposes (an apple will never become an orange). 5. Why are scientific theories rarely discarded (completely abandoned), even when new evidence doesn’t fit within the current theory? Scientific theories are rarely completely discarded because they are heavily-tested and well-supported explanations. It is rare that new evidence completely invalidates a theory; rather, it is more likely that the theory can be “tweaked” or changed slightly to accommodate the new evidence. 6. What represents the BEST explanation that science can offer? Scientific theories represent the best explanations science has to offer. -

Durkheim and Organizational Culture

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #108-04 June 2004 Durkheim and Organizational Culture James R. Lincoln and Didier Guillot Cite as: James R. Lincoln and Didier Guillot. (2004). “Durkheim and Organizational Culture.” IRLE Working Paper No. 108-04. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/108-04.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Durkheim and Organizational Culture James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 Didier Guillot INSEAD Singapore June , 2004 Prepared for inclusion in Marek Kocsynski, Randy Hodson, and Paul Edwards (editors): Social Theory at Work . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Durkheim and Organizational Culture “The degree of consensus over, and intensity of, cognitive orientations and regulative cultural codes among the members of a population is an inv erse function of the degree of structural differentiation among actors in this population and a positive, multiplicative function of their (a) rate of interpersonal interaction, (b) level of emotional arousal, and (c) rate of ritual performance. ” Durkheim’ s theory of culture as rendered axiomatically by Jonathan Turner (1990) Introduction This paper examines the significance of Emile Durkheim’s thought for organization theory , particular attention being given to the concept of organizational culture. We ar e not the first to take the project on —a number of scholars have usefully addressed the extent and relevance of this giant of Western social science for the study of organization and work. Even so, there is no denying that Durkheim’s name appears with vast ly less frequency in the literature on these topics than is true of Marx and W eber, sociology’ s other founding fathers . -

Structuralism 1. the Nature of Meaning Or Understanding

Structuralism 1. The nature of meaning or understanding. A. The role of structure as the system of relationships Something can only be understood (i.e., a meaning can be constructed) within a certain system of relationships (or structure). For example, a word which is a linguistic sign (something that stands for something else) can only be understood within a certain conventional system of signs, which is language, and not by itself (cf. the word / sound and “shark” in English and Arabic). A particular relationship within a شرق combination society (e.g., between a male offspring and his maternal uncle) can only be understood in the context of the whole system of kinship (e.g., matrilineal or patrilineal). Structuralism holds that, according to the human way of understanding things, particular elements have no absolute meaning or value: their meaning or value is relative to other elements. Everything makes sense only in relation to something else. An element cannot be perceived by itself. In order to understand a particular element we need to study the whole system of relationships or structure (this approach is also exactly the same as Malinowski’s: one cannot understand particular elements of culture out of the context of that culture). A particular element can only be studied as part of a greater structure. In fact, the only thing that can be studied is not particular elements or objects but relationships within a system. Our human world, so to speak, is made up of relationships, which make up permanent structures of the human mind. B. The role of oppositions / pairs of binary oppositions Structuralism holds that understanding can only happen if clearly defined or “significant” (= essential) differences are present which are called oppositions (or binary oppositions since they come in pairs). -

THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD and the LAW by Bemvam L

Hastings Law Journal Volume 19 | Issue 1 Article 7 1-1967 The cS ientific ethoM d and the Law Bernard L. Diamond Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bernard L. Diamond, The Scientific etM hod and the Law, 19 Hastings L.J. 179 (1967). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol19/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD AND THE LAW By BEmVAm L. DIivmN* WHEN I was an adolescent, one of the major influences which determined my choice of medicine as a career was a fascinating book entitled Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine. This huge volume, originally published in 1897, is a museum of pictures and lurid de- scriptions of human monstrosities and abnormalities of all kinds, many with sexual overtones of a kind which would especially appeal to a morbid adolescent. I never thought, at the time I first read this book, that some day, I too, would be an anomaly and curiosity of medicine. But indeed I am, for I stand before you here as a most curious and anomalous individual: a physician, psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and (I hope) a scientist, who also happens to be a professor of law. But I am not a lawyer, nor in any way trained in the law; hence, the anomaly. The curious question is, of course, why should a non-lawyer physician and scientist, like myself, be on the faculty of a reputable law school. -

Read Book Writing and Thinking in the Social Sciences 1St Edition

WRITING AND THINKING IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sharon Friedman | 9780139700620 | | | | | Writing and Thinking in the Social Sciences 1st edition PDF Book Psychology is a very broad science that is rarely tackled as a whole, major block. This means that, though anthropologists generally specialize in only one sub-field, they always keep in mind the biological, linguistic, historic and cultural aspects of any problem. For a detailed explanation of typical research paper organization and content, be sure to review Table 3. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. Understanding Academic Writing and Its Jargon The very definition of jargon is language specific to a particular sub-group of people. Notify me of follow-up comments by email. The fields of urban planning , regional science , and planetology are closely related to geography. What might have caused it? It is an application of pedagogy , a body of theoretical and applied research relating to teaching and learning and draws on many disciplines such as psychology , philosophy , computer science , linguistics , neuroscience , sociology and anthropology. The Center is located in Taper Hall, room Historical geography is often taught in a college in a unified Department of Geography. The results section is where you state the outcome of your experiments. This means adding advocacy and activist positions to analysis and the generation of new knowledge. Search this Guide Search. Present your findings objectively, without interpreting them yet. However, what is valued in academic writing is that opinions are based on what is often termed, evidence-based reasoning, a sound understanding of the pertinent body of knowledge and academic debates that exist within, and often external to, your discipline. -

Logical Empiricism / Positivism Some Empiricist Slogans

4/13/16 Logical empiricism / positivism Some empiricist slogans o Hume’s 18th century book-burning passage Key elements of a logical positivist /empiricist conception of science o Comte’s mid-19th century rejection of n Motivations for post WW1 ‘scientific philosophy’ ‘speculation after first & final causes o viscerally opposed to speculation / mere metaphysics / idealism o Duhem’s late 19th/early 20th century slogan: o a normative demarcation project: to show why science ‘save the phenomena’ is and should be epistemically authoritative n Empiricist commitments o Hempel’s injunction against ‘detours n Logicism through the realm of unobservables’ Conflicts & Memories: The First World War Vienna Circle Maria Marchant o Debussy: Berceuse héroique, Élégie So - what was the motivation for this “revolutionary, written war-time Paris (1914), heralds the ominous bugle call of war uncompromising empricism”? (Godfrey Smith, Ch. 2) o Rachmaninov: Études-Tableaux Op. 39, No 8, 5 “some of the most impassioned, fervent work the composer wrote” Why the “massive intellectual housecleaning”? (Godfrey Smith) o Ireland: Rhapsody, London Nights, London Pieces a “turbulant, virtuosic work… Consider the context: World War I / the interwar period o Prokofiev: Visions Fugitives, Op. 22 written just before he fled as a fugitive himself to the US (1917); military aggression & sardonic irony o Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin each of six movements dedicated to a friend who died in the war x Key problem (1): logicism o Are there, in fact, “rules” governing inference -

Positivism and the Inseparability of Law and Morals

\\server05\productn\N\NYU\83-4\NYU403.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-SEP-08 12:20 POSITIVISM AND THE INSEPARABILITY OF LAW AND MORALS LESLIE GREEN* H.L.A. Hart made a famous claim that legal positivism somehow involves a “sepa- ration of law and morals.” This Article seeks to clarify and assess this claim, con- tending that Hart’s separability thesis should not be confused with the social thesis, the sources thesis, or a methodological thesis about jurisprudence. In contrast, Hart’s separability thesis denies the existence of any necessary conceptual connec- tions between law and morality. That thesis, however, is false: There are many necessary connections between law and morality, some of them conceptually signif- icant. Among them is an important negative connection: Law is, of its nature, morally fallible and morally risky. Lon Fuller emphasized what he called the “internal morality of law,” the “morality that makes law possible.” This Article argues that Hart’s most important message is that there is also an immorality that law makes possible. Law’s nature is seen not only in its internal virtues, in legality, but also in its internal vices, in legalism. INTRODUCTION H.L.A. Hart’s Holmes Lecture gave new expression to the old idea that legal systems comprise positive law only, a thesis usually labeled “legal positivism.” Hart did this in two ways. First, he disen- tangled the idea from the independent and distracting projects of the imperative theory of law, the analytic study of legal language, and non-cognitivist moral philosophies. Hart’s second move was to offer a fresh characterization of the thesis.