WORKS REFERRED to Austin,J. L. How to Do Things with Words, Edited by J. O. Urmson, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962. A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ideal Observer Theory and Motivational Internalism

The Ideal Observer Theory and Motivational Internalism Daniel Ronnedal¨ Abstract In this paper I show that one version of motivational internalism follows from the so-called ideal observer theory. Let us call the version of the ideal observer theory used in this essay (IOT). According to (IOT), it is necessarily the case that it ought to be that A if and only if every ideal observer wants it to be the case that A. We shall call the version of motivational internalism that follows from (IOT) (moral) conditional belief motivational internalism (CBMI). According to (CBMI), it is necessarily the case that, for every x: if x were an ideal observer, it would be the case that x believes that it ought to be that A only if x wants it to be the case that A. Given that it is necessarily true that no ideal observer has any false beliefs, (IOT) entails (CBMI). Or, so I shall argue. Keywords: the ideal observer theory, motivational internalism, practical reason 1 Introduction In this paper I show that one version of motivational internalism follows from the so-called ideal observer theory. The classical modern formula- tion of the ideal observer theory is [16].1 According to Roderick Firth, If it is possible to formulate a satisfactory absolutist and dis- positional analysis of ethical statements, it must be possible [. ] to express the meaning of statements of the form \x is right" in terms of other statements which have the form: \Any ideal observer would react to x in such and such a way under such and such conditions." [16, 329] The main idea seems to be that an act is right if and only if (iff) it would be approved by any ideal observer, and more generally that an act has Kriterion { Journal of Philosophy, 2015, 29(1): 79{98. -

Ethical Realism/Moral Realism Ethical Propositions That Refer to Objective Features May Be True If They Are Free of Subjectivis

Metaethics: Cognitivism Metaethics: What is morality, or “right”? Normative (prescriptive) ethics: How should people act? Descriptive ethics: What do people think is right? Applied ethics: Putting moral ideas into practice Thin moral concepts Thick moral concepts more general: good, bad, right, and wrong more specic: courageous, inequitable, just, or dishonest Centralism- thin concepts are antecedent to the thick ones Non-centralism- thick concepts are a sucient starting point for understanding thin ones because thin and thick concepts are equal. Normativity is a non-excisable aspect of language and there is no way of analyzing thick moral concepts into a purely descriptive element attached to a thin moral evaluation, thus undermining any fundamental division between facts and norms. Cognitivism ethical propositions are truth-apt (can be true or false), unlike questions or commands Ethical subjectivism/moral anti-realism Ethical realism/moral realism True ethical propositions are a function of subjective features Ethical propositions that refer to objective features may be true if they are free of subjectivism Moral relativism Moral universalism/ Robust and Minimal Robust moral objectivism/ nobody is objectively right or wrong universal morality 1. Semantic thesis: moral predicates 3. Metaphysical thesis: the facts in regards to diagreements about are to refer to moral properties so and properties of #1 are robust-- moral questions a system of ethics, or a universal ethic, moral statements represent moral their metaphysical status is not applies universally to "all" facts, and express propositions that relevantly dierent from ordinary are true or false non-moral facts and properties Cultural relativism not all forms of moral universalism 2. -

On Three Defenses of Sentimentalism

Prolegomena 12 (1) 2013: 61–82 On Three Defenses of Sentimentalism NORIAKI IWASA Center for General Education, University of Tokushima, 1-1 Minamijosanjima-cho, Tokushima, Tokushima 770-8502, Japan [email protected] ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE / RECEIVED: 02–03–12 ACCEPTED: 12–02–13 ABSTRACT: This essay shows that a moral sense or moral sentiments alone can- not identify appropriate morals. To this end, the essay analyzes three defenses of Francis Hutcheson’s, David Hume’s, and Adam Smith’s moral sense theories against the relativism charge that a moral sense or moral sentiments vary across people, societies, cultures, or times. The first defense is the claim that there is a universal moral sense or universal moral sentiments. However, even if they ex- ist, a moral sense or moral sentiments alone cannot identify appropriate morals. The second defense is to adopt a general viewpoint theory, which identifies moral principles by taking a general viewpoint. But it needs to employ reason, and even if not, it does not guarantee that we identify appropriate morals. The third defense is to adopt an ideal observer theory, which draws moral principles from sentimen - tal reactions of an ideal observer. Yet it still does not show that a moral sense or moral sentiments alone can identify appropriate morals. KEY WORDS : Ethics, Hume, Hutcheson, ideal observer, moral relativism, moral sense, moral sentiment, reason, Smith, universalism. 1. Introduction This essay shows that a moral sense or moral sentiments alone cannot identify appropriate morals. To this end, I analyze three defenses of Fran - cis Hutcheson’s, David Hume’s, and Adam Smith’s moral sense theories against the relativism charge that a moral sense or moral sentiments vary across people, societies, cultures, or times.1 The first defense is the claim 1 Prior to Hutcheson, the third Earl of Shaftesbury used the term ‘moral sense’ in writ - ing. -

Firth's Ideal Observer Theory and Its Problems*

【논문】 Firth’s Ideal Observer Theory * and Its Problems 34) Chung, Hun 【Subject Class】Ethics, Metaethics 【Keywords】Ideal Observer Theory, Firth, Brandt, Dispositional Theory of Value, Ethical Naturalism 【Abstract】There are three main attractions of an ideal observer theory in ethics: (a) it is less ontologically committed by insisting that moral properties are nothing more than the subjective psychological reactions of an idealized human subject, (b) it, nonetheless, preserves our common sense intuition that the truth of ethical statements are prima facie absolute, and (c) it naturalizes ethics by making it an empirical theory that can be pursued in accordance with other scientific disciplines. The purpose of this paper is to introduce and critically analyze an early prototype of such ideal observer theory that was presented by Roderick Firth in 1952. In this paper, I will show how Firth’s ideal observer theory, despite his laborious effort to succeed, fails to meet (b) and (c). Ⅰ. INTRODUCTION: FIRTH’S IDEAL OBSERVER There was a time when many variants of “the ideal observer theory” * This is a shortened version of a much longer paper. If you wish to read the original version, please send me an email at: [email protected] 176 논문 were quite popular among ethical theorists in the analytic tradition.1) However, it seems that ideal observer theories in general have been relatively neglected in the Korean philosophical community. One purpose of this paper is to introduce ideal observer theories to Korean philosophers. Among the many variants of ideal observer theories, this paper will focus on one of the early prototypes of the theory that was presented by Roderick Firth in 1952. -

Hume's General Point of View: a Two-Stage Approach

*Note: this is the penultimate draft; please cite from the published version. Hume’s General Point of View: A Two-Stage Approach Nir Ben-Moshe ([email protected]) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Abstract: I offer a novel two-stage reconstruction of Hume’s general-point-of-view account, modeled in part on his qualified-judges account in ‘Of the Standard of Taste.’ In particular, I argue that the general point of view needs to be jointly constructed by spectators who have sympathized with (at least some of) the agents in (at least some of) the actor’s circles of influence. The upshot of the account is two-fold. First, Hume’s later thought developed in such a way that it can rectify the problems inherent in his Treatise account of the general point of view. Second, the proposed account provides the grounds for an adequate and well-motivated modest ideal observer theory of the standard of virtue. Keywords: David Hume; Ideal Observer; Constructivism; General Point of View; Common Point of View; Standard of Taste 1. Introduction For those who embrace a naturalistic picture of the world and are skeptical about the prospects of meta-ethical realism, an answer to the question of what accounts for the correctness of moral judgment has proven to be elusive. Assuming one wishes to avoid subjectivism and relativism, one could opt for the position that it is the responses of agents who are under suitable conditions that constitute what is morally right. Of course, the conditions in question cannot be defined in terms of these agents getting the right results, on pain of circularity. -

My Understanding of Adam Smith's Impartial Spectator · Econ Journal Watch

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5922 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 13(2) May 2016: 351–358 My Understanding of Adam Smith’s Impartial Spectator Jack Russell Weinstein1 LINK TO ABSTRACT The impartial spectator may be both the least misunderstood and the most controversial aspect of Adam Smith’s work. It is the least misunderstood, because Smith scholars largely agree on its nature. What disagreement there is, tends to be about the details of Smith’s moral psychology. It is the most controversial, however, because many casual Smith readers don’t understand how it fits into his economic theories. This confusion stems from general misperceptions about the unity of Smith’s corpus, but it also speaks to a misunderstanding about the nature of impartiality in general. The impartial spectator is a product of the imagination, in the most literal sense. It exists only in the mind of actual spectators. Since Smith is an empiricist who famously eschews overt metaphysical claims, it is safe to assert that the impar- tial spectator is not real in any Platonic sense. It may have the same ontological status as Homer Simpson or Anna Karenina, but not as the Abrahamic soul or even René Descartes’s mental substance. It is possible to think of the impartial spectator as a construction (I do, at times), but since The Theory of Moral Sentiments predates Immanuel Kant’s relevant work, the Hegelian idealists, and John Rawls, it is unclear what would follow from classifying it as such. Doing so would not make the spectator’s decision objective in the way that Christine Korsgaard argues ethical constructivism demands.2 But, it 1. -

"The Accidental Error Theorist"

- 1 - The accidental error theorist Richard Joyce Penultimate draft of paper appearing in Oxford Studies in Metaethics vol. 6, R. Shafer-Landau (ed.), 2011. Introduction The moral error theorist holds that morality is flawed in the same way as the atheist holds that religion is flawed: The discourse aims at the truth but systematically fails to secure it. Of the various possible arguments that might lead one to this form of moral skepticism, John Mackie’s are best known and most influential (Mackie 1946; 1977; 1980). Mackie’s skeptical case targets both moral prescriptions and moral values, and in both cases it is their putative association with a kind of objectivity that bothers him. He is not an error theorist about prescriptions and values per se; he is always careful to identify the target of his doubt as “objective prescriptions” and “objective values.” It is possible that one might be a moral error theorist for entirely different reasons (see Joyce 2007: 52; Joyce forthcoming), but here we will stick with Mackie’s grounds. The moral error theorist’s opponents can be divided broadly into three types—one of which will be the focus of this paper. First, some opponents are noncognitivists, who deny that moral discourse aims at the truth. For all those remaining opponents we can use the label “success theorists”—those who both embrace cognitivism and hold that moral discourse often succeeds in hitting the truth.1 There are many ways of taxonomizing success theorists, but for present purposes—clarifying types of opposition to Mackie’s error theory—they can be divided into two. -

Virtue Ethics and Professional Roles

VIRTUE ETHICS AND PROFESSIONAL ROLES JUSTIN OAKLEY Monash University DEAN COCKING Charles Sturt University The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge ,UK West th Street, New York, –, USA Stamford Road, Oakleigh, , Australia Ruiz de Alarcón , Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town , South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Justin Oakley and Dean Cocking This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville MT /. pt. System QuarkXPress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Oakley, Justin, – Virtue ethics and professional roles / Justin Oakley, Dean Cocking. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. . Professional ethics. I. Cocking, Dean, – II. Title. . –dc hardback Contents Preface page ix Acknowledgements xii Introduction The nature of virtue ethics The regulative ideals of morality and the problem of friendship A virtue ethics approach to professional roles Ethical models of the good general practitioner Professional virtues, ordinary vices Professional detachment in health care and legal practice Bibliography Index vii The nature of virtue ethics1 -

VIRTUE THEORY and IDEAL OBSERVERS Virtue Theorists In

JASON KAWALL VIRTUE THEORY AND IDEAL OBSERVERS (Received 27 April 2000; received in revised version 19 April 2002) ABSTRACT. Virtue theorists in ethics often embrace the following character- ization of right action: An action is right iff a virtuous agent would perform that action in like circumstances. Zagzebski offers a parallel virtue-based account of epistemically justified belief. Such proposals are severely flawed because virtu- ous agents in adverse circumstances, or through lack of knowledge can perform poorly. I propose an alternative virtue-based account according to which an action is right (a belief is justified) for an agent in a given situation iff an unimpaired, fully-informed virtuous observer would deem the action to be right (the belief to be justified). Virtue theorists in ethics, while primarily united simply in their rejection of familiar deontological and consequentialist theories, do share some common positive ground.1 A standard position among virtue theorists is that what constitutes a morally right action is to be derived (in some way) from the behaviour of virtuous agents. Similarly, in Linda Zagzebski’s recent virtue-based approach in epistemology, justified belief and knowledge are understood in terms of the behaviour of epistemically virtuous agents.2 In what follows I argue that the relation between right action (or justified belief) and virtuous agents espoused by many virtue theorists is severely flawed. However, I also show that a related posi- tion, making use of the judgements of virtuous idealized observers, remains true to the virtue theorists’ insights, but is not subject to the difficulties which beset the standard virtue theory approach. -

A Substantive Revision to Firth's Ideal Observer Theory

Stance | Volume 3 | April 2010 A Substantive Revision to Firth's Ideal Observer Theory ABSTRACT: This paper examines Ideal Observer Theory and uses criticisms of it to lay the foundation for a revised theory first suggested by Jonathan Harrison called Ideal Moral Reaction Theory. Harrison’s Ideal Moral Reaction Theory stipulates that the being producing an ideal moral reaction be dispassionate. This paper argues for the opposite: an Ideal Moral Reaction must be performed by a passionate being because it provides motivation for action and places ethical decision-making within human grasp. Nancy Rankin is a philosophy major and religious studies minor at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tennessee. Her philosophical interests mainly center around ethical theory and the philosophy of religion. In her spare time, she enjoys reading and plans to become a fiction author sometime in the near future. n an article titled “Ethical Absolutism and the of Ideal Observer Theory which can be termed Ideal Observer,” Roderick Firth advocates Ideal Moral Reaction Theory. Although this theory a theory that has come to be known as the was first suggested by Jonathan Harrison, I make a Ideal Observer Theory. Ideal Observer Theory substantive revision to his conception of the theory asserts that right and wrong are determined by an when I argue that an individual attempting an ideal Iideal observer’s reaction to a given act. That is, any moral reaction would be a passionate being, rather act X is morally permissible if an ideal observer than the dispassionate one Harrison suggests. This, would approve of X; conversely, any act Y is I argue, places ethical decision-making within morally blameworthy if an ideal observer would the grasp of human beings and thus makes it a disapprove of Y. -

The Absolutist Criteria of Roderick Firth's Ideal Observer Theory

The absolutist criteria of Roderick Firth’s ideal observer theory Mikael Barclay Supervisor: Lars Samuelsson Mikael Barclay Spring 2016 Bachelor’s thesis, philosophy, 15 credits Department of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies Abstract Meta-ethical theories take a number of different ontological, epistemic and semantic positions. In 1952 Roderick Firth published the article “Ethical absolutism and the ideal observer”, in which he defends and shares his own version of a theory on the meaning of ethical expressions, referred to as the ideal observer theory (IOT). The IOT essentially suggests that the truth value of an ethical expression could in principle be determined by knowing the ethically significant reaction it would evoke on an ideal observer (IO), of certain ideal psychological characteristics, should such a being exist. These characteristics are being understood in terms of an ideal practice of justification for actions. For instance, we might hold that in order to be a competent moral judge, we must have sufficient knowledge of the circumstances which we are to assess, or that we are not somehow biased. Firth suggests that an ideal observer has the characteristics of omniscience to non- ethical facts, omnipercipience, disinterest, dispassion and consistency. The theory itself is described as being absolutist, dispositional, objectivist, relational and possibly empirical. The specific research question of this paper regards the theory’s ability to give a plausible and meaningful explanation as to the meaning of ethical expressions, while maintaining its absolutist characteristic. The presented conclusion holds that: (i) the ethically significant reaction of IOs cannot be conflicting, (ii) that knowing the characteristics of the IO is not in principle necessary for the form and validity of the theory, (iii) that such form presupposes actual IO characteristics based on an assumption about the human nature and (iv) that ‘IO’ designates a hypothetical reference through a circular definition. -

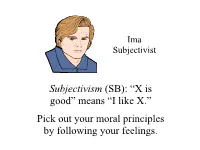

Subjectivism (SB): “X Is Good” Means “I Like X.” Pick out Your Moral Principles by Following Your Feelings. Subjectivism

Ima Subjectivist Subjectivism (SB): “X is good” means “I like X.” Pick out your moral principles by following your feelings. Subjectivism preserves our moral freedom, solves CR’s subgroup problem, fits how we form moral beliefs, fits how we speak (“I like smoking but it isn’t good” means “I like the enjoyment of smoking but I don’t like the consequences of smoking”), avoids the illusion of moral objectivity. A problem with SB SB can make goodness depend totally on irrational feelings. If “X is good” means “I like X,” then this reasoning is valid: I like hurting people. ∴ Hurting people is good. This is bad logic (what I like needn’t be good) and a crude way to think about values (feelings may be selfish or based on false beliefs). Apply subjectivism to global moral racism warming education Ima Idealist Ideal Observer View (IO): “X is good” means “We’d desire X if we were fully informed and had impartial concern for everyone.” Pick out your moral principles by trying to become as informed and impartial as possible – and then seeing what you desire. How would IO criticize these? I like smoking. ∴ Smoking is good. I like hurting people. ∴ Hurting people is good. Apply the ideal observer view to global moral racism warming education Problems with ideal observer view Ideal observers might not always agree. It’s impossible for us to be fully informed. “Impartial” is vague. Does it require us to have equal concern for everyone (the same for our child and for a complete stranger)? Moral rationality may require other factors besides knowledge and impartial concern.