Block-3 Meta-Ethics Meta-Ethics BLOCK INTRODUCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noncognitivism and Autonomy Eamonn Callan

Document generated on 09/23/2021 5:34 p.m. Philosophical Inquiry in Education Noncognitivism and Autonomy Eamonn Callan Volume 23, Number 2, 2016 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070470ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1070470ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Philosophy of Education Society ISSN 2369-8659 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Callan, E. (2016). Noncognitivism and Autonomy. Philosophical Inquiry in Education, 23(2). https://doi.org/10.7202/1070470ar Copyright ©, 2016 Eamonn Callan This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Noncognitivism and Autonomy Eamonn Callan, University of Alberta The supposed failure of ethical cognitivism is the beginning of one com mon argument for the ideal of personal autonomy and its supporting social practices. The argument can be summarized as follows. There is no ethical knowledge that could conceivably be available to us, or at least all current claims to such knowledge are doubtful to a degree that makes them untenable. Therefore, experts to whose authority we should defer regarding ethical deci sions simply do not exist. That is tantamount to saying we should act autonomously in making ethical decisions and, if we are to grant the capacity and liberty to make such decisions to others, we need to develop educational and other social practices that nurture the relevant capacity and bestow the necessary liberty. -

The Ideal Observer Theory and Motivational Internalism

The Ideal Observer Theory and Motivational Internalism Daniel Ronnedal¨ Abstract In this paper I show that one version of motivational internalism follows from the so-called ideal observer theory. Let us call the version of the ideal observer theory used in this essay (IOT). According to (IOT), it is necessarily the case that it ought to be that A if and only if every ideal observer wants it to be the case that A. We shall call the version of motivational internalism that follows from (IOT) (moral) conditional belief motivational internalism (CBMI). According to (CBMI), it is necessarily the case that, for every x: if x were an ideal observer, it would be the case that x believes that it ought to be that A only if x wants it to be the case that A. Given that it is necessarily true that no ideal observer has any false beliefs, (IOT) entails (CBMI). Or, so I shall argue. Keywords: the ideal observer theory, motivational internalism, practical reason 1 Introduction In this paper I show that one version of motivational internalism follows from the so-called ideal observer theory. The classical modern formula- tion of the ideal observer theory is [16].1 According to Roderick Firth, If it is possible to formulate a satisfactory absolutist and dis- positional analysis of ethical statements, it must be possible [. ] to express the meaning of statements of the form \x is right" in terms of other statements which have the form: \Any ideal observer would react to x in such and such a way under such and such conditions." [16, 329] The main idea seems to be that an act is right if and only if (iff) it would be approved by any ideal observer, and more generally that an act has Kriterion { Journal of Philosophy, 2015, 29(1): 79{98. -

Unit 13 Emotivism: Charles Stevenson*

Emotivism: Charles UNIT 13 EMOTIVISM: CHARLES Stevenson STEVENSON* Structure 13.0 Objectives 13.1 Introduction 13.2 Definition 13.3 The Significance of Emotivism in Moral Philosophy 13.4 Philosophical Views 13.5 Let Us Sum Up 13.6 Key Words 13.7 Further Readings and References 13.8 Answers to Check Your Progress 13.0 OBJECTIVES This unit provides: An introductory understanding and significance of emotivism in moral and ethical philosophy. Many aspects of emotivism have been explored by philosophers in the history of modern philosophy but this unit focuses Charles Stevenson’s version of emotivism. 13.1 INTRODUCTION Emotivism is a meta-ethical theory in moral philosophy, which was developed by the American philosopher Charles Stevenson (1908-1978). He was born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1908. He studied philosophy under G E Moore and Ludwig Wittgenstein, and was most influenced by the latter. From 1933 onwards, and continuing after the war, he developed the emotive theory of ethics at the University of Harvard. Stevenson’s contributions were largely in the area of meta-ethics. Post-war debates in the field of ethics were charceterised by ‘the linguistic turn’ in philosophy, and the increasing emphasis of scientific knowledge on philosophy, especially under the influence of the school of Logical Positivism. Questions such as, do ‘scientific facts’ play a role in ethical considerations? how far feelings and emotions influence our understanding of morality?, became significant. Therefore, to respond to these and related issues, philosophers developed different ethical theories. Stevenson was one of the philosophers who developed the theory of emotivism against this backdrop, and defended his theory to justify how feelings and non-cognitive attributes constitute our understanding of morality and moral judgments. -

The Theory of Justice

Syllabus of the course: The Theory of Justice Утверждена Академическим советом ООП Протокол № 1от «31» августа 2018 г. Pre-requisites This course is based on knowledge and competences which were provided by the following disciplines: ● History of Philosophy ● General Ethics ● Analytic Ethics ● Political Philosophy ● Political Science Course Type: Elective Learning Objectives The objective of the course make the students familiar with the major contemporary theories of justice and the development of the necessary analytic skills of evaluation of any normative conception of justice as well as the capacity to participate in the public discourse on justice, which is about to emerge. Course Plan Ethics, Morality, Justice Language, Logic and Meaning of Justice Utilitarian Theory of Justice The Theory of Justice of John Rawls The Justice of Political Liberalism Libertarian Theory of Justice by Robert Nozick Justice by Agreement by David Gauthier Marxism as a Theory of Justice Feminism and Justice Communitarian Critique of Justice Just War Theory The Russian Historical Discourse of Justice 1. Ethics, Morality, Justice Ethics. The meaning of Ethics and Morality. Ethical Theory, General Ethics and Individual Ethics. The History of Morality. The Sociology of Morality. The Psychology of Morality. The stages of moral growth. Moralism, Immoralism, Amoralism. Human nature. Ethical skepticism. Metaethics. Theories of Metaethics. Naturalism. Emotivism. Universal Prescriptivism. Intuitivism. The nature of moral concepts. Good and Evil. Moral Relativism. Sentimentalism. Normative Morals. Moral Theory. Egoism. Psychological Egoism. Religious Ethics. Convention. Particularism. Teleological Ethics. Consequentialism. Utilitarianism. Hedonism. Deontology. Kant’s categorical imperative. Virtue Ethics. Morality and Rationality. Negative versus Politive Rights and Duties. Elitism. Applied Ethics. -

Ethical Realism/Moral Realism Ethical Propositions That Refer to Objective Features May Be True If They Are Free of Subjectivis

Metaethics: Cognitivism Metaethics: What is morality, or “right”? Normative (prescriptive) ethics: How should people act? Descriptive ethics: What do people think is right? Applied ethics: Putting moral ideas into practice Thin moral concepts Thick moral concepts more general: good, bad, right, and wrong more specic: courageous, inequitable, just, or dishonest Centralism- thin concepts are antecedent to the thick ones Non-centralism- thick concepts are a sucient starting point for understanding thin ones because thin and thick concepts are equal. Normativity is a non-excisable aspect of language and there is no way of analyzing thick moral concepts into a purely descriptive element attached to a thin moral evaluation, thus undermining any fundamental division between facts and norms. Cognitivism ethical propositions are truth-apt (can be true or false), unlike questions or commands Ethical subjectivism/moral anti-realism Ethical realism/moral realism True ethical propositions are a function of subjective features Ethical propositions that refer to objective features may be true if they are free of subjectivism Moral relativism Moral universalism/ Robust and Minimal Robust moral objectivism/ nobody is objectively right or wrong universal morality 1. Semantic thesis: moral predicates 3. Metaphysical thesis: the facts in regards to diagreements about are to refer to moral properties so and properties of #1 are robust-- moral questions a system of ethics, or a universal ethic, moral statements represent moral their metaphysical status is not applies universally to "all" facts, and express propositions that relevantly dierent from ordinary are true or false non-moral facts and properties Cultural relativism not all forms of moral universalism 2. -

Truth: in Ethics and Elsewhere

ANALYTIC TEACHING Vol. 19, No 1 Truth: In Ethics and Elsewhere This paper was presented at the North American Association for Community of Inquiry (NAACI) conference held in La Crosse, Wisconsin, USA, in July, 1998. Susan T. Garder All truths wait in all things, They neither hasten their own discovery nor resist it .... Walt Whitman, «Song of Myself» THE SEDUCTION OF RELATIVITY t is popular to make the claim, particularly when it comes to questions of value, that there is no I such thing as «truth.» For some, a belief in social or cultural relativism is the source of such scepticism. Such individuals would argue that it is chauvinistic arrogance to believe that just because, from one’s own point of view, practices carried out by other cultures appear to be immoral, e.g., cliterodectomies on unwilling young women, that somehow they are immoral per se. Others would argue for an even more radical form of relativism, no doubt stemming from a misguided view of equal- ity, namely that any individual viewpoint is a good (or bad) as anyone else’s: «from my point of view `x’ is immoral, but I wouldn’t dream of saddling anyone else with my morals.» Still others believe that, despite the drawbacks of a relativistic position, they must nonetheless remain sceptical about the possi- bility of truth in ethics in order to distance themselves from those who have inflicted enormous harm on others in the name of having a privileged access to truth. The Spanish inquisition, the holocaust, the decimation of indigenous people, were all carried out by individuals most of whom believed that they had truth on their side. -

Eritis Sicut Deus: Moral Theory and the Sin of Pride

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Asbury Theological Seminary Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 3 Issue 4 Article 4 10-1-1986 Eritis Sicut Deus: Moral Theory and the Sin of Pride Gilbert Meilaender Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Meilaender, Gilbert (1986) "Eritis Sicut Deus: Moral Theory and the Sin of Pride," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 3 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol3/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. ERITIS SICUT DEUS: MORAL THEORY AND THE SIN OF PRIDE Gilbert Meilaender The fundamental temptation, especially for those who are serious about the moral life, is always the same: failing in trust, to want to be like God, knowing good and evil. "What the serpent has in mind," Karl Barth has written, "is the establishment of ethics. "1 This is an overstatement, but it points us toward an important truth. The number of possible moral theories is not large, though their varieties are infinitely complex. C. S. Lewis has a simple illustration which directs attention to the features of life that any moral theory must consider. Think of us as a fleet of ships sailing in formation. -

THE UNIVERSITY of WESTERN ONTARIO DEPARTMENT of PHILOSOPHY Graduate Course Outline 2016-17

THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY Graduate Course Outline 2016-17 Philosophy 9653A: Proseminar Fall Term 2016 Instructor: Robert J. Stainton Class Days and Hours: W 2:30-5:30 Office: StH 3126 Office Hours: Tu 2:00-3:00 Classroom: TBA Phone: 519-661-2111 ext. 82757 Web Site: Email: [email protected] http://publish.uwo.ca/~rstainto/ Blog: https://robstainton.wordpress.com/ DESCRIPTION A survey of foundational and highly influential texts in Analytic Philosophy. Emphasis will be on four sub-topics, namely Language and Philosophical Logic, Methodology, Ethics and Epistemology. Thematically, the focal point across all sub-topics will be the tools and techniques highlighted in these texts, which reappear across Analytic philosophy. REQUIRED TEXT A.P. Martinich and David Sosa (eds.)(2011) Analytic Philosophy: An Anthology. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [All papers except the Stine and Thomson are reprinted here.] OBJECTIVES The twin objectives are honing of philosophical skills and enriching students’ familiarity with some “touchstone” material in 20th Century Analytic philosophy. In terms of skills, the emphasis will be on: professional-level philosophical writing; close reading of notoriously challenging texts; metaphilosophical reflection; and respectful philosophical dialogue. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Twelve weekly “Briefing Notes” on Selected Readings: 60% Three “Revised Brief Notes”: 25% Class Participation: 15% COURSE READINGS Language and Philosophical Logic Gottlob Frege (1892), “On Sense and Reference” Gottlob Frege (1918), “The Thought” Bertrand Russell (1905), “On Denoting” Ludwig Wittgenstein (1933-35 [1958]), Excerpts from The Blue and Brown Books Peter F. Strawson (1950), “On Referring” H. Paul Grice (1957), “Meaning” H. Paul Grice (1975), “Logic and Conversation” Saul Kripke (1971), “Identity and Necessity” Hilary Putnam (1973), “Meaning and Reference” Methodology A.J. -

A Defence of Emotivism

A Defence of Emotivism Leslie Allan Published online: 16 September 2015 Copyright © 2015 Leslie Allan As a non-cognitivist analysis of moral language, Charles Stevenson’s sophisticated emotivism is widely regarded by moral philosophers as a substantial improvement over its historical antecedent, radical emotivism. None the less, it has come in for its share of criticism. In this essay, Leslie Allan responds to the key philosophical objections to Stevenson’s thesis, arguing that the criticisms levelled against his meta-ethical theory rest largely on a too hasty reading of his works. To cite this essay: Allan, Leslie 2015. A Defence of Emotivism, URL = <http://www.RationalRealm.com/philosophy/ethics/defence-emotivism.html> To link to this essay: www.RationalRealm.com/philosophy/ethics/defence-emotivism.html Follow this and additional essays at: www.RationalRealm.com This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sublicensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms and conditions of access and use can be found at www.RationalRealm.com/policies/tos.html Leslie Allan A Defence of Emotivism 1. Introduction In this essay, my aim is to defend an emotive theory of ethics. The particular version that I will support is based on C. L. Stevenson’s signal work in Ethics and Language [1976], originally published in 1944, and his later revisions and refinements to this theory presented in his book, Facts and Values [1963]. I shall not, therefore, concern myself with the earlier and less sophisticated versions of the emotive theory, such as those presented by A. -

Essays on Ethical Universalizability

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications - Department of Philosophy Philosophy, Department of 1985 Introduction from Morality and Universality: Essays on Ethical Universalizability Nelson T. Potter University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Mark Timmons University of Illinois Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/philosfacpub Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, and the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Potter, Nelson T. and Timmons, Mark, "Introduction from Morality and Universality: Essays on Ethical Universalizability" (1985). Faculty Publications - Department of Philosophy. 23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/philosfacpub/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Philosophy by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Potter & Timmons in Nelson Potter and Mark Timmons (editors), Morality and Universality, ix-xxxii. Copyright 1985, D. Reidel Publishing. Used by permission. INTRODUCTION In the past 25 years or so, the issue of ethical universalizability has figured prominently in theoretical as well as practical ethics. The term, ‘universalizability’ used in connection with ethical considerations, was apparently first introduced in the mid-1950s by R. M. Hare to refer to what he characterized as a logical thesis -

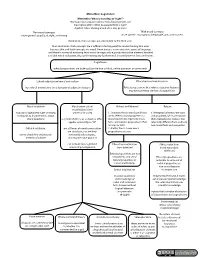

A “Family Tree” of Ethical Theories

A “Family Tree” of Ethical Theories [This is section 10.10 of the draft of my book The Marxist-Leninist-Maoist Class Interest Theory of Ethics. –JSH] Chart 10.1 in this section is an effort to depict the relationships between the various types of ethical theories, and specifically how other ethical theories relate to the MLM class interest theory of ethics. The idea is to look for the most fundamental division among the various types of theories and to separate them into two groups on that basis. Then to further divide the remaining theories in each group in the same way, leading to sort of a “family tree” of ethical theories based—not on how they actually evolved—but rather on how they relate to each other logically. The chart has a lot of information in it and may be somewhat hard to initially comprehend. For that reason I am further explaining it below. In the chart I have also printed in red the attributes or categories which encompass the two moral systems supported by MLM ethical theory (i.e., proletarian morality and communist morality). The first big division among ethical theories is between COGNITIVISM and NON- COGNITIVISM. Cognitivism holds that moral judgments are meaningful, and that they are true or false. Somewhat amazingly, there are numerous theories of ethics which deny this, and hence deny that it is meaningful and/or true to say, for example, that genocide is wrong! The logical positivists, in particular, claimed that moral judgments are meaningless. Some people in this general positivist tradition, including Charles Stevenson, went on to claim that moral judgments are merely expressions of emotion and “commands” that others have the same emotional reaction to something as the speaker does. -

Justification and Moral Cognitivism

Department of Theology Spring Term 2018 Master's Thesis in Human Rights 30 ECTS Justification and Moral Cognitivism An Analysis of Jürgen Habermas’s Metaethics Author: Johan Elfström Supervisor: Professor Elena Namli Abstract In this thesis, I scrutinise and interpret Jürgen Habermas’s claim that justification of moral norms necessitates cognitivism. I do this by analysing the general idea behind his discourse theory of morality and then his metaethics. From there, I examine the non-cognitivist theory called prescriptivism as set out by Richard Hare to see if his account of moral reasoning is able to counter Habermas’s claims and thereafter, I examine some criticism against his concept of communicative action. I also engage with the discussion on how to define cognitivism: that is, whether the line should be drawn between moral realism on the cognitivist side, and constructivism on the other, or if cognitivism can include constructivist theories too. I propose that it should, provided that it allows moral statements to be truth-apt and express a mental state like that of belief. Following this definition, I argue that Habermas can be labelled a cognitivist and finally, I conclude that Habermas argument does not hold under scrutiny. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1. Cognitivism and Rational Justification ........................................................................... 2 1.2. Previous Research ..........................................................................................................