Texas Treasury Notes After the Compromise of 1850

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compromise of 1850 Earlier You Read About the Missouri Compromise and the Wilmot Proviso

Compromise of 1850 Earlier you read about the Missouri Compromise and the Wilmot Proviso. Keep them in mind as you read here What is a compromise? A compromise is a resolution of a problem in which each side gives up demands or makes concession. Earlier you read about the Missouri Compromise. What conflict did it resolve? It kept the number of slave and free states equal by admitting Maine as free and Missouri as slave and it provided for a policy with respect to slavery in the Louisiana Territory. Other than in Missouri, the Compromise prohibited slavery north of 36°30' N latitude in the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. Look at the 1850 map. Notice how the "Missouri Compromise Line" ends at the border to Mexican Territory. In 1850 the United States controls the 36°30' N latitude to the Pacific Ocean. Will the United States allow slavery in its new territory? Slavery's Expansion Look again at this map and watch for the 36°30' N latitude Missouri Compromise line as well as the proportion of free and slave states up to the Civil War, which begins in 1861. WSBCTC 1 This map was created by User: Kenmayer and is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license (CC-BY 3.0) [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_Slave_Free_1789-1861.gif]. Here's a chart that compares the Missouri Compromise with the Compromise of 1850. WSBCTC 2 Wilmot Proviso During the Mexican-American War in 1846, David Wilmot, a Democratic congressman from Pennsylvania, proposed in an amendment to a military appropriations bill that slavery be banned in all the territories acquired from Mexico. -

Omnibus Budget Bills and the Covert Dismantling of Canadian Democracy

Omnibus Budget Bills and the Covert Dismantling of Canadian Democracy by Jacqueline Kotyk supervised by Dr. Dayna Scott A Major Project submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada July 31, 2017 1 Foreword: My major project, which is a study on the rise of omnibus budget bills in Canadian Parliament, supports my learning objectives and the curriculum developed in my plan of study in a number of ways. Initially, and as expounded upon in my major paper proposal, this project was intended to aid in my understanding of the role of law in extractive capitalism as the bills were linked to deregulation of extractive industries. In addition, the bills were at once decried as a subversion of Canadian democracy and also lawful, and thus I understood that an examination of the bills would assist me in understanding the manner in which law mediates power in the Canadian state. I further wanted to focus on legislative process to comprehend potential points of resistance in the Canadian Parliamentary regime. Upon the completion of this project, I enhanced my understanding on the above learning objectives and much more. This project on omnibus budget bills also brought with it a focused examination of the construction of the neoliberal political project and its influence on power relations within extractive capitalism. In addition, I gained knowledge of the integral role of law reform in re-structuring capitalist social relations such that they enhance the interests of the economic elites. -

8Th Grade Social Studies Lesson 3

8th Grade Social Studies Lesson 3 Students will be reading a graphic text about the Compromise of 1850. They will then take a 10 question reading comprehension quiz over the graphic text. (8.1.24) During this lesson students will demonstrate their mastery of the following learning targets; ● Identify the causes and effects of events leading to the Civil War.(Compromise of 1850) During the lesson students will know they have mastered those learning targets because they are able to show they have fulfilled the following Success Criteria; ● Identify the causes and effects of events leading to the Civil War.(Compromise of 1850) ○ I can identify how the Compromise of 1850 led to the Civil War Summary: Students will read a graphic text about the Compromise of 1850 and answer 10 questions about the text. Directions: 1. Step 1 - Read the following graphic text https://drive.google.com/file/d/1--fa6zgt5XOSXE4p_P4eZKLPmDuUvUaw/view?usp=sha ring 2. Step 2 - Complete the following quiz over the Compromise of 1850 https://drive.google.com/open?id=1-MGyX0xXSLlEkPRSWBW6-lFXvh3MOB6S Resources: Text - https://drive.google.com/file/d/1--fa6zgt5XOSXE4p_P4eZKLPmDuUvUaw/view?usp=sharing Quiz - https://drive.google.com/open?id=1-MGyX0xXSLlEkPRSWBW6-lFXvh3MOB6S In 1846, Polk gains the Oregon territory. More future northern free states. some panic for the south. Then Polk's war with Mexico gains an even greater amount of land that could potentially become southern slave states. Wait a minute, say northern democrats who oppose the spread of slavery to any more of the lands belonging to the United States. -

Immigrant Policy Project August 6, 2012 2012 Immigration-Related

Immigrant Policy Project August 6, 2012 2012 Immigration-Related Laws and Resolutions in the States (January 1 – June 30, 2012) Overview: In 2012, the introduction and enactment of immigration bills and resolutions in the states dropped markedly from previous years. Legislators found that state budget gaps and redistricting maps took priority, consuming much of the legislative schedule. Perhaps more significant, state lawmakers cited pending litigation on states’ authority to enforce immigration laws as further reason to postpone action. This summer’s U.S. Supreme Court ruling on Arizona v. United States upheld only one of the four state provisions challenged by the U.S. Department of Justice. That provision allows law enforcement officers to inquire about a person’s immigration status during a lawful stop. In 2011, five states enacted legislation similar to Arizona’s: Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina and Utah. The lower courts have either partially or wholly enjoined these statutes. Still pending in Arizona is a class action lawsuit to test additional constitutional questions not considered in Arizona v. United States. These include: the Fifth Amendment right to due process, First Amendment right to free speech and 14th Amendment right to equal protection. Also pending are complaints filed by the federal government against immigration enforcement laws enacted in 2011 in Alabama, South Carolina and Utah. Report Highlights State lawmakers in 46 states and the District of Columbia introduced 948 bills and resolutions related to immigrants and refugees from Jan. 1 to June 30, 2012. This is a 40-percent drop from the peak of 1,592 in the first half of 2011. -

Chart of Other States' Enacted Legislation.Xlsx

APPENDIX B: CHART OF ENACTED LEGISLATION IN OTHER STATES State Type of Legislation Summary Adopts the policy and procedure of the Legislative Council, prohibiting sexual harassment by members, officers, employees, lobbyists and other persons working in the legislature, as the sexual harassment policy of the Al. Senate. Alabama Senate Resolution 51 Policy specifies “touching a person’s body, hair or clothing or standing to close to, brushing up against or cornering a person,” and unwelcome and personally offensive behavior as prohibited. Prohibits a non-disclosure agreement from barring a party from responding to a peace officer or prosecutor’s inquiry or making a HB 2020 statement in a criminal proceeding in relation to an alleged violation of a sexual offense or obscenity under the Criminal Code. Arizona Expels Rep. Don Shooter from the House of Reps following an investigation by bipartisan team and special counsel found credible House Resolution 2003 evidence that he violated the House policy prohibiting sexual harassment and pattern of conduct dishonorable and unbecoming a member Creates the Legislative Employee Whistleblower Protection Act establishing criminal and civil protections for employees in the event AB 403 they are retaliated against for making a good faith allegation against a member or staffer for violating any law, including sexual harassment or violating a legislative code of conduct. Requires all publicly traded companies filing incorporation letters with the Secretary of State in California to have at least one woman on their SB 826 board by the close of 2019 and increase the number to at least 2 females on its board of directors by the end of 2021. -

The Wilmot Proviso the Wilmot Proviso Was a Rider (Or Provision) Attached to an Appropriations Bill During the Mexican War

The Wilmot Proviso The Wilmot Proviso was a rider (or provision) attached to an appropriations bill during the Mexican War. It stated that slavery would be banned in any territory won from Mexico as a result of the war. While it was approved by the U.S. House of Representatives (where northern states had an advantage due to population), it failed to be considered by the U.S. Senate (where slave and free states were evenly divided). Though never enacted, the Wilmot Proviso signaled significant challenges regarding what to do with the extension of slavery into the territories. The controversy over slavery’s extension polarized public opinion and resulted in dramatically increased sectional tension during the 1850s. The Wilmot Proviso was introduced by David Wilmot from Pennsylvania and mirrored the wording of the Northwest Ordinance on slavery. The proviso stated “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory” that might be gained from Mexico as a result of the Mexican-American War. The issue of the extension of slavery was not new. As northern states abolished the institution of slavery, they pushed to keep the practice from extending into new territory. The push for abolition began before the ratification of the Constitution with the enactment of the Northwest Ordinance which outlawed slavery in the Northwest Territory. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 brought a large amount of new land into the U.S. that, over time, would qualify for territorial status and eventually statehood. The proviso stated “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory” that might be gained from Mexico as a result of the Mexican-American War. -

From the Omnibus Act of 1988 to the Trade Act of 2002

AMERICAN TRADE POLITICS: From the Omnibus Act of 1988 To The Trade Act of 2002 Kent Hughes Director, Project on America and the Global Economy Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars A paper prepared for presentation at the Congress Project/Project on America and the Global Economy seminar on “Congress and Trade Policy” at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, November 17, 2003 Kent Hughes, Project on America and the Global Economy 2 Introduction: In 1988, the Congress passed the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 with broad bipartisan support. Unlike most post-World War II trade legislation, the Omnibus Act originated with the Congress rather than with a proposal from the Administration. Despite continuing Administration objections, final passage came in 1988 by wide margins in both the House and the Senate. In addition to a comprehensive competitiveness or productivity growth strategy, the Omnibus Act included negotiating objectives and fast track authority. Under fast track procedures, the Congress agreed to an up or down vote on future trade agreements without the possibility of adding any amendments. Neither the fast track procedures nor the bill’s negotiating objectives were particularly controversial at the time. Fast track authority (for completing negotiations) lapsed on June 1, 1993. President Clinton unsuccessfully sought to renew fast track authority in 1997. He tried again in 1998 only to lose decisively in the House of Representatives. In 2001, a new Administration made securing Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), a new name for fast track, an early Administration priority. Yet despite a newly elected Republican President, George W. -

Perspectives on Statehood: South Dakota's First Quarter Century, 1889-1914

Copyright © 1989 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. Perspectives on Statehood: South Dakota's First Quarter Century, 1889-1914 HOWARD R. LAMAR Copyright © 1989 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. •if South Dakota History It is likely that the year 1914 will he practically forgot- ten in Smith Dakota history, f<yr there has been no extraor- dinary event from, which dates may be kept. The people are prosperous and go about their affairs cheerfully and hopefully. Clearly we are growing self-satisfied, but not ungrateful to the Giver of All Good Gifts. —Doane Robinson, "Projircss of South Dakota, 1914" South Dakota Historical Collections (1916) In an overview of the history of the states comprising the Great Plains, historian James E. Wright has written that the region and its people moved into maturity between the 188()s and World War I. In the process, Wright continues, its inhabitants "underwent three primary types of adaptation to the new reality of western life: political, technological, and psychological."' As every stu- dent of South Dakota history knows, the state is not wholly em- braced by the Great Plains; nevertheless Wright's generalizations provide a useful framework by which to assess the changes that occurred in South Dakota during its first quarter century of state- hood. Of course, turning points or significant events for one group were less so for others. If one noted changes in South Dakota's Indian population in the years 1889-1914, for example, it would be more accurate to speak of psychological change first, and then economic and political change, in that order. -

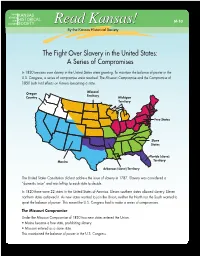

Read Kansas! Read Kansas!

YOUR KANSAS STORIES HISTORICAL OUR M-10 HISTORY SOCIETY Read Kansas! By the Kansas Historical Society The Fight Over Slavery in the United States: A Series of Compromises In 1820 tensions over slavery in the United States were growing. To maintain the balance of power in the U.S. Congress, a series of compromise were reached. The Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850 both had effects on Kansas becoming a state. Missouri Oregon Territory Country Michigan Territory Free States Slave States Florida (slave) Mexico Territory Arkansas (slave) Territory The United States Constitution did not address the issue of slavery in 1787. Slavery was considered a “domestic issue” and was left up to each state to decide. In 1820 there were 22 states in the United States of America. Eleven southern states allowed slavery. Eleven northern states outlawed it. As new states wanted to join the Union, neither the North nor the South wanted to upset the balance of power. This meant the U.S. Congress had to make a series of compromises. The Missouri Compromise Under the Missouri Compromise of 1820 two new states entered the Union. • Maine became a free state, prohibiting slavery. • Missouri entered as a slave state. This maintained the balance of power in the U.S. Congress. The Missouri Compromise did something else that made it important. • For the first time the federalgovernment, rather than the states, decided on the issue of slavery. • The compromise banned slavery in the northern portion of the Louisianam Territory. This included the land that was to become Kansas. The Compromise of 1850 The Compromise of 1850 was a series of bills that passed the U.S. -

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850: the Tipping Point

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850: The Tipping Point During the Antebellum period, tensions between the Northern and Southern regions of the United States escalated due to debates over slavery and states’ rights. These disagreements between the North and South set the stage for the Civil War in 1861. Following the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the United States acquired 500,000 square miles of land from Mexico and the question of whether slavery would be allowed in the territory was debated between the North and South. As a solution, Congress ultimately passed the The Compromise of 1850. The Compromise resulted in California joining the Union as a free state and slavery in the territories of New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona and Utah, to be determined by popular sovereignty. In order to placate the Southern States, the Fugitive Slave Act was put into place to appease the Southerners and to prevent secession. This legislation allowed the federal government to deputize Northerners to capture and return escaped slaves to their owners in the South. Although the Fugitive Slave Act was well intentioned, the plan ultimately backfired. The Fugitive Slave Act fueled the Abolitionist Movement in the North and this angered the South. The enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act increased the polarization of the North and South and served as a catalyst to events which led to the outbreak of the Civil War. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 brought into sharp focus old differences between the North and South and empowered the Anti-Slavery movement. Prior to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the Act of 1793 was passed and this allowed for slave owners to enter free states to capture escaped slaves. -

Slavery and the Civil War

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Slavery and the Civil War www.nps.gov The role of slavery in bringing on the Civil War has been hotly debated for decades. One important way of approaching the issue is to look at what contemporary observers had to say. In March 1861, Alexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederate States of America, gave his view: The new [Confederate] constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution — African slavery as it exists amongst us — the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution . The prevailing ideas entertained by . most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically . Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error . Alexander H. Stephens, vice Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its president of the Confederate corner–stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that States of America. slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition. — Alexander H. Stephens, March 21, 1861, reported in the Savannah Republican, emphasis in the original. Today, most professional historians agree with Stephens that could not be ignored. -

John C. Fremont and the Violent Election of 1856

Civil War Book Review Fall 2017 Article 9 Lincoln's Pathfinder: John C. rF emont And The Violent Election Of 1856 Stephen D. Engle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Engle, Stephen D. (2017) "Lincoln's Pathfinder: John C. rF emont And The Violent Election Of 1856," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 19 : Iss. 4 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.19.4.14 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol19/iss4/9 Engle: Lincoln's Pathfinder: John C. Fremont And The Violent Election Of Review Engle, Stephen D. Fall 2017 Bicknell, John Lincoln’s Pathfinder: John C. Fremont and the Violent Election of 1856. Chicago Review Press, $26.99 ISBN 1613737971 1856: Moment of Change The famed historian David Potter once wrote that if John Calhoun had been alive to witness the election of 1856, he might have observed “a further snapping of the cords of the Union.” “The Whig cord had snapped between 1852 and 1856,” he argued “and the Democratic cord was drawn very taut by the sectional distortion of the party’s geographical equilibrium.” According to Potter, the Republican party “claimed to be the only one that asserted national principles, but it was totally sectional in its constituency, with no pretense to bi-sectionalism, and it could not be regarded as a cord of the Union at all.”1 He was right on all accounts, and John Bicknell captures the essence of this dramatic political contest that epitomized the struggle of a nation divided over slavery. To be sure, the election of 1856 marked a turning point in the republic’s political culture, if for no other reason than it signaled significant change on the democratic horizon.