Intuition and Awareness of Abstract Models: a Challenge for Realists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Perceptual Skills

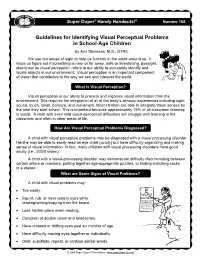

Super Duper® Handy Handouts!® Number 168 Guidelines for Identifying Visual Perceptual Problems in School-Age Children by Ann Stensaas, M.S., OTR/L We use our sense of sight to help us function in the world around us. It helps us figure out if something is near or far away, safe or threatening. Eyesight, also know as visual perception, refers to our ability to accurately identify and locate objects in our environment. Visual perception is an important component of vision that contributes to the way we see and interpret the world. What Is Visual Perception? Visual perception is our ability to process and organize visual information from the environment. This requires the integration of all of the body’s sensory experiences including sight, sound, touch, smell, balance, and movement. Most children are able to integrate these senses by the time they start school. This is important because approximately 75% of all classroom learning is visual. A child with even mild visual-perceptual difficulties will struggle with learning in the classroom and often in other areas of life. How Are Visual Perceptual Problems Diagnosed? A child with visual perceptual problems may be diagnosed with a visual processing disorder. He/she may be able to easily read an eye chart (acuity) but have difficulty organizing and making sense of visual information. In fact, many children with visual processing disorders have good acuity (i.e., 20/20 vision). A child with a visual-processing disorder may demonstrate difficulty discriminating between certain letters or numbers, putting together age-appropriate puzzles, or finding matching socks in a drawer. -

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory What is Metacognition? The simplest definition of metacognition is “thinking about thinking.” This refers to the “self-regulation” effective learners exhibit, meaning they are aware of their learning process and can measure how efficiently they are learning as they study. Essentially, metacognition involves two simultaneous levels of thought: the first level is the student’s thinking/learning about the specific subject content and the second level is the student’s thinking about his/her learning. A student practicing metacognition would ask him/herself “How am I thinking?” or “Where am I in the learning process? Am I learning/understanding this topic? How could I learn more effectively?” These two levels are: knowledge and regulation. Students who are metacognitively aware demonstrate self-knowledge: They know what strategies and conditions work best for them while they are learning. Declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge are essential for developing conceptual knowledge (content knowledge). Regulation refers to students’ knowledge about the implementation of strategies and the ability to monitor the effectiveness of their strategies. When students regulate, they are continually developing and monitoring their learning strategies based on their evolving self-knowledge. Complete the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory to assess your metacognitive processes. The Inventory Check True or False for each statement below. After you complete the inventory, use the scoring guide. Contact an Academic Coach at the Academic Support Center at (856) 681-6250 to discuss your results and strategies to increase your metacognitive awareness. True False 1. I ask myself periodically if I am meeting my goals. 2. I consider several alternatives to a problem before I answer. -

Will It Blend? Information Systems and Computer Engineering

Will It Blend? Studying Color Mixing Perception Paulo Duarte Esperanc¸a Garcia Thesis to obtain the Master of Science Degree in Information Systems and Computer Engineering Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Prof. Dra. Sandra Pereira Gama Examination Committee Chairperson: Prof. Dr. Antonio´ Manuel Ferreira Rito da Silva Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Member of the Committee: Prof. Dr. Manuel Joao˜ Caneira Monteiro da Fonseca November 2016 Acknowledgments First, I want to thank my advisor Professor Daniel Gonc¸alves for his excellent guidance, for always having the availability to teach, help and clarify, for his enormous knowledge and expertise, and for al- ways believing in the best result possible of this Master Thesis. Then, I also want to thank my co-advisor Sandra Gama, for her more-than-valuable inputs on Information Visualization and for opening the path for this dissertation and others to come! Additionally, I would like to thank everyone which somehow contributed for this thesis to happen: everyone who participated either online, or on the laboratory sessions, specially those who did it so willingly, without looking at the rewards. Without them, there would be no validity is this thesis. I must express my very profound gratitude to my family, particularly my mother Ondina and brother Diogo, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study and through the process of researching and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you! Finally, to my girlfriend Margarida, my beloved partner, my shelter and support, for all the sleepless nights, sweat and tears throughout the last seven years. -

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

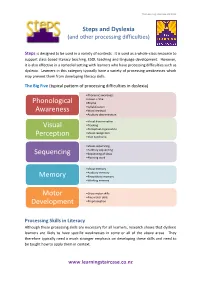

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word. -

The Natural Power of Intuition

THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES by Jessica Jagtiani Dissertation Committee: Professor Judith Burton, Sponsor Professor Mary Hafeli Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date 16 May 2018 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2018 ABSTRACT THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES Jessica Jagtiani Both artists and business executives state the importance of intuition in their professional practice. Current research suggests that intuition plays a significant role in cognition, decision-making, and creativity. Intuitive perception is beneficial to management, entrepreneurship, learning, medical diagnosis, healing, spiritual growth, and overall well-being, and is furthermore, more accurate than deliberative thought under complex conditions. Accordingly, acquiring intuitive faculties seems indispensable amid present day’s fast-paced multifaceted society and growing complexity. Today, there is an overall rising interest in intuition and an existing pool of research on intuition in management, but interestingly an absence of research on intuition in the field of art. This qualitative-phenomenological study explores the experience of intuition in both professional practices in order to show comparability and extend the base of intuition, while at the same time revealing what is unique about its emergence in art practice. Data gathered from semi-structured interviews and online-journals provided the participants’ experience of intuition and are presented through individual portraits, including an introduction to their work, their worldview, and the experiences of intuition in their lives and professional practice. -

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) The trait MAAS is a 15-item scale designed to assess a core characteristic of mindfulness, namely, a receptive state of mind in which attention, informed by a sensitive awareness of what is occurring in the present, simply observes what is taking place. Brown, K.W. & Ryan, R.M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822-848. Carlson, L.E. & Brown, K.W. (2005). Validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in a cancer population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 29-33. Instructions: Below is a collection of statements about your everyday experience. Using the 1-6 scale below, please indicate how frequently or infrequently you currently have each experience. Please answer according to what really reflects your experience rather than what you think your experience should be. Please treat each item separately from every other item. 1 2 3 4 5 6 almost very somewhat somewhat very almost never always frequently frequently infrequently infrequently _____ 1. I could be experiencing some emotion and not be conscious of it until some time later. _____ 2. I break or spill things because of carelessness, not paying attention, or thinking of something else. _____ 3. I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present. _____ 4. I tend to walk quickly to get where I’m going without paying attention to what I experience along the way. _____ 5. I tend not to notice feelings of physical tension or discomfort until they really grab my attention. -

Perception Without Awareness*

PERCEPTION WITHOUT AWARENESS* Fred Dretske We appear to be on the horns of a dilemma with respect to the criteria for consciousness. Phenomenological criteria are valid by definition but do not appear to be scientific by the usual yardsticks. Behavioral criteria are scientific by definition but are not necessarily valid. --Stephen Palmer in Vision Science: Photons to Phenomenology (p. 629) Unknown to Sarah, her neighbor, a person she sees every day, is a spy. When she sees him, therefore, she sees him without awareness of either the fact that he is a spy or the fact that she sees a spy. Why, then, isn't the existence of perception without awareness (or, as some call it, implicit or subliminal perception) a familiar piece of commonsense rather than a contentious issue in psychology?1 It isn't only spies. We see armadillos, galvanometers, cancerous growths, divorcees, and poison ivy without realizing we are seeing any such thing. Most (all?) things can be, and often are (when seen at a distance or bad light), seen without awareness of what is being seen and, therefore, without awareness that one is seeing something of that sort. Why, then, is there disagreement about unconscious perception? Isn't perception without awareness the rule rather than a disputed exception to the rule? I deliberately misrepresent what perception without awareness is supposed to be in order to emphasize an important preliminary point--the difference between awareness of a stimulus (an object of some sort) and awareness of facts about it—including the fact that one is aware of it. -

Assessment and Intervention of Visual Perception and Cognition Following Brain Injury and the Impact on Everyday Functioning

Assessment and Intervention of Visual Perception and Cognition Following Brain Injury and the Impact on Everyday Functioning. Kara Christy, MS, OTRL, CBIS Natasha Huffine, MS, OTRL, CBIS Vision and the Brain •Occipital Lobe • Temporal Lobe • Primary visual cortex • Combines sensory information • Visual association cortex associated with the recognition and identification of objects such • Analyzing orientation, position, and as people, places, and things. movement. • Initiation of Smooth Pursuit Movements • Parietal Lobe • Visual Field Loss • Locating objects • Eye movements • Drawing/construction of objects •Frontal Lobe • Neglect • Saccades and Attention • Movement through space 2 Definitions Visual Perception is the ability to interpret, understand, and define incoming visual information. Form Constancy is the ability to identify objects despite their variation of size, color, shape, position, or texture. Figure ground Perception is the ability to distinguish foreground from background. Visual Closure is the ability to accurately identify objects that are partially covered or missing. Spatial Orientation is the ability to recognize personal position in relation to opposing positions, directions, movement of objects, and environmental locations. Unilateral Inattention is phenomenon that causes one to experience an inability to orient and respond to contralateral visual information. Depth Perception is the ability to perceive relative distance in environmental objects. Visual Memory is the ability to take in a visual stimulus, retain its details, and store for later retrieval. Visual Motor Integration is accurate and quick communication between the eyes and hands. Visuocognition is the ability to use visual information to solve problems, make decisions, and complete planning and organizational tasks through mental manipulation. Executive Functioning is the ability to reason, plan, problem solve, make inferences, and/or evaluate results of actions and decisions. -

Attention Awareness and Noticing Revised JW

Attention, awareness, and noticing in language processing and learning John N. Williams. Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, University of Cambridge, U.K. A slightly revised version of this manuscript appeared in J. M. Bergsleithner & S. N. Frota & J. K. Yoshioka (Eds.), Noticing and Second Language Acquisition: Studies in Honor of Richard Schmidt (pp. 39-57). Honolulu, Hawai'i: National Foreign Language Resource Centre. 2013. Abstract This chapter reviews current psychological and applied linguistic research that is relevant to Schmidt’s landmark theoretical analysis of the concepts of attention, conscious awareness, and noticing. Recent evidence that attention and awareness are dissociable makes it possible to ask which of these constructs is required for either processing familiar stimuli, or learning novel associations. There is good evidence for processing familiar stimuli without conscious awareness, and even without attention. There is mounting evidence for learning without awareness at the level of understanding regularities, particularly when meaning is involved (semantic implicit learning). There is even some recent evidence for learning without awareness at the level of noticing form, for example learning associations between subliminal and liminal words. Thus, whilst attention does appear to be necessary for learning, awareness might not be. It is suggested that future research should probe the types of regularity that can be learned without awareness, and that this will shed more light on the nature of the underlying learning mechanism, and permit an evaluation of its relevance to SLA. Author Bio John Williams graduated in Psychology at the University of Durham, U.K., and then went on to do doctoral research at the Medical Research Council Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, receiving a PhD from the University of Cambridge for work on semantic processing during spoken language comprehension. -

How to Use the Artwork R S E a M I C T H C a L L V I

H D T E C N I R A C P L X E E HOW TO USE THE ARTWORK R S E A M I C T H C A L L V I The 2018 National Crime Victims’ Rights Week Resource Artwork Categories Guide offers a selection of professionally developed, original illustration and other artwork to promote this To help you select the most suitable file, 2018 NCVRW year’s theme—Expand the Circle: Reach All Victims. Draw Resource Guide artwork is categorized by how it will be attention to your community’s NCVRW observance by used: learning how to match the theme colors, which fonts to • Web Art—JPEG files in RGB at pixel dimensions use, what kind of file is best suited for your purpose, and commonly used in website and email templates. other recommendations to make the most of this year’s These images will display properly onscreen and guide. load quickly due to their small file size, but may By using the 2018 Resource Guide artwork, you appear pixelated or very small in print applications. become part of the nationwide effort to raise awareness • Print Art—high-resolution JPEG or PDF exports about crime victims’ rights and services during National set up in CMYK, suitable for office printing or for Crime Victims’ Rights Week. placing into other documents. (Note that these files do not account for a “bleed”—when the ink for an Artwork Elements image extends beyond the borders of the page.) • Press Art—high-resolution source files in CMYK with This year’s artwork frames the 2018 NCVRW theme— outlined text, embedded images, and document Expand the Circle: Reach All Victims—as a call to op- bleeds. -

The Biology of Awareness by Ursula Goodenough, Big History Project on 08.05.16 Word Count 1,188 Level MAX

The biology of awareness By Ursula Goodenough, Big History Project on 08.05.16 Word Count 1,188 Level MAX TOP: Bullfrog hiding in duckweed. BOTTOM: Neurons. Courtesy of Big History Project. One of the amazing complexities of life is an organism's ability to recognize and react to its surroundings. This trait of awareness exists in the smallest single-celled organism as well as in the most complex of creatures — that is, Homo sapiens, like you and me. Emergence A living organism has thousands of different kinds of protein shapes, enabling it to self-organize and self-maintain, to reproduce and adapt. How is this even possible inside of a single cell? One useful way to think about this is with a concept called "emergence." There's a T-shirt slogan for emergence that goes, "You get something else from nothing but." What does that mean? Well, the nothing buts are important parts of a system that form relationships with, and organize themselves with respect to, one another. When that happens, the something else that wasn't there before, a new property or capability, pops through. Let's think of some examples. We might consider an emergent property like blood circulation. The nothing buts are things like the heart, the arteries, and the capillaries that, working collectively, allow for blood circulation to take place. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. There's a useful term in biology for emergent properties: traits. So blood circulation is a trait. Human-style motility is a trait, and there are countless others. -

It's a Colorful Life

It’s a Colorful Life Dr. Lawrence D. Woolf [email protected] General Atomics Presented at the 2001 Teachers Day April Meeting of the American Physical Society Washington DC April 30, 2001 Q SCIENCES EDUCATION FOUNDATION GENERAL ATOMICS Why Learn about Color and Color Vision in a Physics Class? "There are many interesting phenomena associated with vision which involve a mixture of physical phenomena and physiological processes, and the full appreciation of natural phenomena, as we see them, must go beyond physics in the usual sense. We make no apologies for making these excursions into other fields, because the separation of fields, as we have emphasized, is merely a human convenience, and an unnatural thing. Nature is not interested in our separations, and many of the interesting phenomena bridge the gap between fields.“ Feynman Lectures on Physics, Volume 1, Chapter 35 (Color Vision) Q SCIENCES EDUCATION FOUNDATION GENERAL ATOMICS Why study color? • Most interesting new physics and technology is multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary – Color is a model system • Note the variety of models and methods we will use to explore color Q SCIENCES EDUCATION FOUNDATION GENERAL ATOMICS Color: An Ideal System for Using and Understanding Models • Wide Variety of Different Color Models: inter-related – Color math - addition/subtraction/algebra/multiplication/fractions – RBG color space - color monitors – CMY color space - color printing – L*a*b* color space - most common in technology- color distance – CIE xyY chromaticity diagram - color science