How Intuition Contributes to High Performance: an Educational

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Perceptual Skills

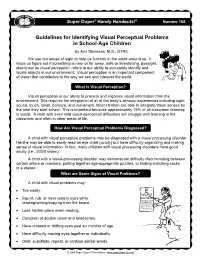

Super Duper® Handy Handouts!® Number 168 Guidelines for Identifying Visual Perceptual Problems in School-Age Children by Ann Stensaas, M.S., OTR/L We use our sense of sight to help us function in the world around us. It helps us figure out if something is near or far away, safe or threatening. Eyesight, also know as visual perception, refers to our ability to accurately identify and locate objects in our environment. Visual perception is an important component of vision that contributes to the way we see and interpret the world. What Is Visual Perception? Visual perception is our ability to process and organize visual information from the environment. This requires the integration of all of the body’s sensory experiences including sight, sound, touch, smell, balance, and movement. Most children are able to integrate these senses by the time they start school. This is important because approximately 75% of all classroom learning is visual. A child with even mild visual-perceptual difficulties will struggle with learning in the classroom and often in other areas of life. How Are Visual Perceptual Problems Diagnosed? A child with visual perceptual problems may be diagnosed with a visual processing disorder. He/she may be able to easily read an eye chart (acuity) but have difficulty organizing and making sense of visual information. In fact, many children with visual processing disorders have good acuity (i.e., 20/20 vision). A child with a visual-processing disorder may demonstrate difficulty discriminating between certain letters or numbers, putting together age-appropriate puzzles, or finding matching socks in a drawer. -

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory What is Metacognition? The simplest definition of metacognition is “thinking about thinking.” This refers to the “self-regulation” effective learners exhibit, meaning they are aware of their learning process and can measure how efficiently they are learning as they study. Essentially, metacognition involves two simultaneous levels of thought: the first level is the student’s thinking/learning about the specific subject content and the second level is the student’s thinking about his/her learning. A student practicing metacognition would ask him/herself “How am I thinking?” or “Where am I in the learning process? Am I learning/understanding this topic? How could I learn more effectively?” These two levels are: knowledge and regulation. Students who are metacognitively aware demonstrate self-knowledge: They know what strategies and conditions work best for them while they are learning. Declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge are essential for developing conceptual knowledge (content knowledge). Regulation refers to students’ knowledge about the implementation of strategies and the ability to monitor the effectiveness of their strategies. When students regulate, they are continually developing and monitoring their learning strategies based on their evolving self-knowledge. Complete the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory to assess your metacognitive processes. The Inventory Check True or False for each statement below. After you complete the inventory, use the scoring guide. Contact an Academic Coach at the Academic Support Center at (856) 681-6250 to discuss your results and strategies to increase your metacognitive awareness. True False 1. I ask myself periodically if I am meeting my goals. 2. I consider several alternatives to a problem before I answer. -

Holism in Deep Ecology and Gaia-Theory: a Contribution to Eco-Geological

M. Katičić Holism in Deep Ecology and Gaia-Theory: A Contribution to Eco-Geological... ISSN 1848-0071 UDC 171+179.3=111 Recieved: 2013-02-25 Accepted: 2013-03-25 Original scientific paper HOLISM IN DEEP ECOLOGY AND GAIA-THEORY: A CONTRIBUTION TO ECO-GEOLOGICAL SCIENCE, A PHILOSOPHY OF LIFE OR A NEW AGE STREAM? MARINA KATINIĆ Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, Croatia e-mail: [email protected] In the second half of 20th century three approaches to phenomenon of life and environmental crisis relying to a holistic method arose: ecosophy that gave impetus to the deep ecology movement, Gaia-hypothesis that evolved into an acceptable scientific theory and gaianism as one of the New Age spiritual streams. All of this approaches have had different methodologies, but came to analogous conclusions on relation man-ecosystem. The goal of the paper is to introduce the three approaches' theoretical and practical outcomes, compare them and evaluate their potency to stranghten responsibility of man towards Earth ecosystem which is a self-regulating whole which humanity is part of. Key words: holism, ecosophy, deep ecology movement, gaia-theory, new age, responsibility. Holizam u dubinskoj ekologiji i teoriji Geje: doprinos ekogeološkoj znanosti, filozofija života ili struja New agea? U drugoj polovici 20. stoljeća pojavila su se tri pristupa fenomenu života i ekološkoj krizi s osloncem u holističkoj metodi: ekozofija koja je dala poticaj razvoju pokreta dubinske ekologije, hipoteza Geje koja se razvila u prihvatljivu znanstvenu teoriju i gajanizam kao jedna od New Age duhovnih struja. Ova su se tri pristupa služila različitim metodama, no došla su do analognih zaključaka o odnosu čovjek-ekosustav. -

Destined for Shamanic Inspiration. an Integrative Study of Buryat (Neo)Shamans

109 Destined for Shamanic Inspiration. An Integrative Study of Buryat (Neo)Shamans Valentina Kharitonova and Yulia Ukraintseva Introduction Altered states of consciousness (ASCs) experienced from time to time by people of creative professions, adepts of different religious and magical- mystical cults, people taking hallucinogenic, narcotic, alcoholic drugs, and individuals with mental issues or diseases, attract more and more interest of researchers in various scientific areas. In this respect the research field of ethnology and folklore studies allows to study (in collaboration with neurophysiologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, etc.) adepts of various religious and magical-mystical practices (including shamanism), performers of epic songs, storytellers - to number several of them. At present this field includes, first of all, neo-shamans1, folk healers and adepts of some neo religious movements (Kharitonova et al. 2008). All of them quite knowingly resort to ASCs, many of them do this not out of mere curiosity, but feeling a need to experience these states. Among above mentioned practitioners there are people who fall hostage to ASCs, because, on the one hand, their organisms can not function normally 1 In the context o f Russia the term neo-shaman is used in relation to representatives of those peoples who have had well-developed shamanism until quite recently. These people, as a rule, resorted to the shamanic practice of their ethnic tradition indirectly in the context of “rebirth of shamanism” by attending courses of healing, magic, bioenergotherapy, or learning from any of the “new shamans”. The term urban shaman is used to refer to representatives of non-shamanic ethnic groups practicing in big Russian cities (for details see: Kharitonova 2006). -

Will It Blend? Information Systems and Computer Engineering

Will It Blend? Studying Color Mixing Perception Paulo Duarte Esperanc¸a Garcia Thesis to obtain the Master of Science Degree in Information Systems and Computer Engineering Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Prof. Dra. Sandra Pereira Gama Examination Committee Chairperson: Prof. Dr. Antonio´ Manuel Ferreira Rito da Silva Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Member of the Committee: Prof. Dr. Manuel Joao˜ Caneira Monteiro da Fonseca November 2016 Acknowledgments First, I want to thank my advisor Professor Daniel Gonc¸alves for his excellent guidance, for always having the availability to teach, help and clarify, for his enormous knowledge and expertise, and for al- ways believing in the best result possible of this Master Thesis. Then, I also want to thank my co-advisor Sandra Gama, for her more-than-valuable inputs on Information Visualization and for opening the path for this dissertation and others to come! Additionally, I would like to thank everyone which somehow contributed for this thesis to happen: everyone who participated either online, or on the laboratory sessions, specially those who did it so willingly, without looking at the rewards. Without them, there would be no validity is this thesis. I must express my very profound gratitude to my family, particularly my mother Ondina and brother Diogo, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study and through the process of researching and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you! Finally, to my girlfriend Margarida, my beloved partner, my shelter and support, for all the sleepless nights, sweat and tears throughout the last seven years. -

Clairvoyance by C.W

Clairvoyance by C.W. Leadbeater Clairvoyance by C.W. Leadbeater Published in 1899 London: The Theosophical Publishing Society 26, Charing Cross, S.W. Chapter -1- WHAT CLAIRVOYANCE IS Chapter -2- SIMPLE CLAIRVOYANCE: FULL Chapter -3- SIMPLE CLAIRVOYANCE: PARTIAL Chapter -4- CLAIRVOYANCE IN SPACE: INTENTIONAL Chapter -5- CLAIRVOYANCE IN SPACE: SEMI-INTENTIONAL Chapter -6- CLAIRVOYANCE IN SPACE: UNINTENTIONAL Chapter -7- CLAIRVOYANCE IN TIME: THE PAST Chapter -8- CLAIRVOYANCE IN TIME: THE FUTURE Chapter -9- METHODS OF DEVELOPMENT Page 1 Clairvoyance by C.W. Leadbeater Chapter -1- WHAT CLAIRVOYANCE IS [Page 5] Clairvoyance means literally nothing more than "clear seeing", and it is a word which has been sorely misused, and even degraded so far as to be employed to describe the trickery of a mountebank in a variety show. Even in its more restricted sense it covers a wide range of phenomena, differing so greatly in character that it is not easy to give a definition of the word which shall be at once succinct and accurate. It has been called "spiritual vision", but no rendering could well be more misleading than that, for in the vast majority of cases there is no faculty connected with it which has the slightest claim to be honoured by so lofty a name. For the purpose of this treatise we may, perhaps, define it as the power to see what is hidden from ordinary physical sight. It will be as well to premise that it is very frequently ( though by no means always ) accompanied by what is called clairaudience, or the power to hear what would be inaudible to the ordinary physical [Page 6] ear; and we will for the nonce take our title as covering this faculty also, in order to avoid the clumsiness of perpetually using two long words where one will suffice. -

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

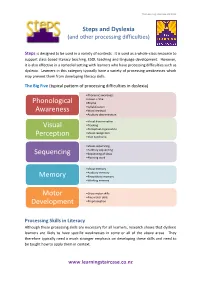

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word. -

Leadership Intuition Meets the Future of Work

How Well Do Executives Trust Their Intuition? Leadership Intuition Meets the Future of Work 7 Leadership Intuition Meets the Future of Work Written by: David Dye Contributing Writers: Chiara Corso, Claradith Landry, Jennifer Rompre, Kyle Sandell, and William Tanner CONTENTS Shifting Society, Shifting Leadership Needs ................................................109 A Framework for Developing Informed Intuition .....................................112 Informed Intuition in Practice ......................................................................115 How to Develop Informed Intuition ............................................................119 Acknowledgments ..........................................................................................121 Notes ................................................................................................................121 “We’re gonna be in the Hudson,” the pilot said to air traffic control. The weather in New York on January 15, 2009 was pleasant, but the inside of the cockpit of US Airways Flight 1549 was anything but. As the plane plummeted toward the river, the automated proximity warning system chanted, Pull up! Pull up! Pull up! “Got flaps out,” said the co-pilot. “You want more?” Pull up! Pull up! Pull up! “No, let’s stay at two,” the pilot replied. Caution, terrain! Pull up! Pull up! Pull up! “This is the captain,” he announced over the intercom. “Brace for impact.” Terrain! Terrain! Pull up! Pull up! He turned to his co-pilot. “Got any ideas?” Pull up! Pull up! Pull up! -

The Natural Power of Intuition

THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES by Jessica Jagtiani Dissertation Committee: Professor Judith Burton, Sponsor Professor Mary Hafeli Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date 16 May 2018 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2018 ABSTRACT THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES Jessica Jagtiani Both artists and business executives state the importance of intuition in their professional practice. Current research suggests that intuition plays a significant role in cognition, decision-making, and creativity. Intuitive perception is beneficial to management, entrepreneurship, learning, medical diagnosis, healing, spiritual growth, and overall well-being, and is furthermore, more accurate than deliberative thought under complex conditions. Accordingly, acquiring intuitive faculties seems indispensable amid present day’s fast-paced multifaceted society and growing complexity. Today, there is an overall rising interest in intuition and an existing pool of research on intuition in management, but interestingly an absence of research on intuition in the field of art. This qualitative-phenomenological study explores the experience of intuition in both professional practices in order to show comparability and extend the base of intuition, while at the same time revealing what is unique about its emergence in art practice. Data gathered from semi-structured interviews and online-journals provided the participants’ experience of intuition and are presented through individual portraits, including an introduction to their work, their worldview, and the experiences of intuition in their lives and professional practice. -

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) The trait MAAS is a 15-item scale designed to assess a core characteristic of mindfulness, namely, a receptive state of mind in which attention, informed by a sensitive awareness of what is occurring in the present, simply observes what is taking place. Brown, K.W. & Ryan, R.M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822-848. Carlson, L.E. & Brown, K.W. (2005). Validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in a cancer population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 29-33. Instructions: Below is a collection of statements about your everyday experience. Using the 1-6 scale below, please indicate how frequently or infrequently you currently have each experience. Please answer according to what really reflects your experience rather than what you think your experience should be. Please treat each item separately from every other item. 1 2 3 4 5 6 almost very somewhat somewhat very almost never always frequently frequently infrequently infrequently _____ 1. I could be experiencing some emotion and not be conscious of it until some time later. _____ 2. I break or spill things because of carelessness, not paying attention, or thinking of something else. _____ 3. I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present. _____ 4. I tend to walk quickly to get where I’m going without paying attention to what I experience along the way. _____ 5. I tend not to notice feelings of physical tension or discomfort until they really grab my attention. -

Perception Without Awareness*

PERCEPTION WITHOUT AWARENESS* Fred Dretske We appear to be on the horns of a dilemma with respect to the criteria for consciousness. Phenomenological criteria are valid by definition but do not appear to be scientific by the usual yardsticks. Behavioral criteria are scientific by definition but are not necessarily valid. --Stephen Palmer in Vision Science: Photons to Phenomenology (p. 629) Unknown to Sarah, her neighbor, a person she sees every day, is a spy. When she sees him, therefore, she sees him without awareness of either the fact that he is a spy or the fact that she sees a spy. Why, then, isn't the existence of perception without awareness (or, as some call it, implicit or subliminal perception) a familiar piece of commonsense rather than a contentious issue in psychology?1 It isn't only spies. We see armadillos, galvanometers, cancerous growths, divorcees, and poison ivy without realizing we are seeing any such thing. Most (all?) things can be, and often are (when seen at a distance or bad light), seen without awareness of what is being seen and, therefore, without awareness that one is seeing something of that sort. Why, then, is there disagreement about unconscious perception? Isn't perception without awareness the rule rather than a disputed exception to the rule? I deliberately misrepresent what perception without awareness is supposed to be in order to emphasize an important preliminary point--the difference between awareness of a stimulus (an object of some sort) and awareness of facts about it—including the fact that one is aware of it. -

Assessment and Intervention of Visual Perception and Cognition Following Brain Injury and the Impact on Everyday Functioning

Assessment and Intervention of Visual Perception and Cognition Following Brain Injury and the Impact on Everyday Functioning. Kara Christy, MS, OTRL, CBIS Natasha Huffine, MS, OTRL, CBIS Vision and the Brain •Occipital Lobe • Temporal Lobe • Primary visual cortex • Combines sensory information • Visual association cortex associated with the recognition and identification of objects such • Analyzing orientation, position, and as people, places, and things. movement. • Initiation of Smooth Pursuit Movements • Parietal Lobe • Visual Field Loss • Locating objects • Eye movements • Drawing/construction of objects •Frontal Lobe • Neglect • Saccades and Attention • Movement through space 2 Definitions Visual Perception is the ability to interpret, understand, and define incoming visual information. Form Constancy is the ability to identify objects despite their variation of size, color, shape, position, or texture. Figure ground Perception is the ability to distinguish foreground from background. Visual Closure is the ability to accurately identify objects that are partially covered or missing. Spatial Orientation is the ability to recognize personal position in relation to opposing positions, directions, movement of objects, and environmental locations. Unilateral Inattention is phenomenon that causes one to experience an inability to orient and respond to contralateral visual information. Depth Perception is the ability to perceive relative distance in environmental objects. Visual Memory is the ability to take in a visual stimulus, retain its details, and store for later retrieval. Visual Motor Integration is accurate and quick communication between the eyes and hands. Visuocognition is the ability to use visual information to solve problems, make decisions, and complete planning and organizational tasks through mental manipulation. Executive Functioning is the ability to reason, plan, problem solve, make inferences, and/or evaluate results of actions and decisions.