Great Gatsby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Narrative Approach to the Philosophical Interpretation Of

A NARRATIVE APPROACH TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL INTERPRETATION OF DREAMS, MEMORIES, AND REFLECTIONS OF THE UNCONSCIOUS THROUGH THE USE OF AUTOETHNOGRAPHY/BIOGRAPHY A Dissertation by ANTONIO RIVERA ROSADO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction A NARRATIVE APPROACH TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL INTERPRETATION OF DREAMS, MEMORIES, AND REFLECTIONS OF THE UNCONSCIOUS THROUGH THE USE OF AUTOETHNOGRAPHY/BIOGRAPHY A Dissertation by ANTONIO RIVERA ROSADO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, Stephen Carpenter Patrick Slattery Committee Members, Valerie Hill-Jackson Toby Egan Head of Department, Dennie Smith May 2011 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction iii ABSTRACT A Narrative Approach to the Philosophical Interpretation of Dreams, Memories, and Reflections of the Unconscious Through the Use of Autoethnography/Biography. (May 2011) Antonio Rivera Rosado, B.A., Interamerican University of Puerto Rico; M.Ed., The University of Texas at El Paso Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee, Dr. Stephen Carpenter Dr. Patrick Slattery The purpose of the present study aimed to develop a comprehensive model that measures the autoethnographic/biographic relevance of dreams, memories, and reflections as they relate to understanding the self and others. A dream, memory, and reflection (DMR) ten item questionnaire was constructed using aspects of Freudian, Jungian, and Lacanian Theory of Dream Interpretation. Fifteen dreams, five memories, and five reflections were collected from the participant at the waking episode or during a moment of deep thought. -

By David Rothfuss Fireworks and Sex! Is a New

ABSTRACT FIREWORKS AND SEX! by David Rothfuss Fireworks and Sex! is a new religion I’m launching so I can get rich without paying taxes. The religious document that follows, which you’re probably not even allowed to read on account of copyright restrictions, is pretty standard as religious documents go, providing you, the religious consumer, with 205 pages of morally ambiguous poems, fables and doodles to base your life upon. It is by far the most American religion out there, and a sure-fire path to a shinier existence, with the average follower experiencing 74% more happiness, 93% more freedom, and 87% more American Dream than those in other religions. If you were allowed to read it, which you’re not, it would provide you with an inside track to God and eternal salvation. FIREWORKS AND SEX A Field Study Guide to America’s Shiniest Religion A Thesis Submitted to the faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of the Arts Creative Writing/Poetry Department of English by David Alexander Rothfuss Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2011 Keith Tuma, advisor cris cheek, reader David Schloss, reader . © David Rothfuss 2011 Table of Contents: Book 1: Concerning this Book, its characters and the partial revelation of truths……………………………………………………………….………...p.1 Book 2: Concerning your new religion and how lost you would be without it…p. 52 A Brief Interlude: Poems upon which you shall base your life…………..p. 88 Book 3: Big Time: in which Our now famous characters hash out their differences with God and mortality………………………………………………………p. -

SING-A-LONG BOOK (Revision Two, August, 2007)

AN UNOFFICIAL ALLEY SING-A-LONG BOOK (Revision Two, August, 2007) AN UNOFFICIAL ALLEY SING-A-LONG BOOK (Revision Two, August 2007 Acknowledgments: Original Concept, Research, Layout and Design: Robert V. Carey Assistant: Joanne M. Binder Edited by: Robert V. Carey & Paul Rose Revision One Research and Layout: Paul Rose Revision Two Research and Layout: Paul Rose Special Appreciation for Sponsorship: Richard McCall, Dave Chapman, Kitty Explanation of Abbreviations (w) “words by” (P) “Popularized by” (CR) "Cover Record" i.e., a (m) “music by” (R) “Rerecorded by” competing record made of the same (wm) “words and music by” (RR) “Revival Recording” song shortly after the original record (I) “Introduced by” (usually the first has been issued record) NARAS Award Winner –Grammy Award The contents of this volume are intended solely for entertainment purposes. The contents contained herein are not to be distributed in whole or in part for commercial use. All copyrights, international and otherwise are secured and reserved by the copyright holders. For all works contained herein: Unauthorized copying, arranging, adapting, recording or public performance for commercial gain is an infringement of copyright. If you “accidentally” take this book home, shame on you. These books have been donated by other patrons of The Alley. Please know that each copy cost one of your fellow singers about $14. CALL ME IRRESPONSIBLE .......................... 12 A CAN’T HELP FALLING IN LOVE WITH YOU ..................................................................... 14 A, YOU’RE ADORABLE (THE ALPHABET CAN’T HELP LOVIN’ DAT MAN .................. 13 SONG) ........................................................... 1 CAN’T WE BE FRIENDS ............................... 14 ABA DABA HONEYMOON, THE ..................... 1 CAROLINA IN THE MORNING .................... -

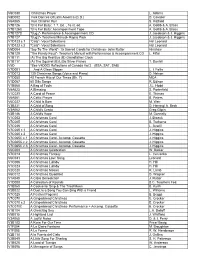

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

V-By Song Title

V6C030 Christmas Prayer L. Adams V8D002 Folk Dances Of Latin America (C.D.) D. Cavalier V6A065 Run Children Run S. Hatfield V7B126 "B Is For Bully: 1 T. Ed. , 16 st. ed. A. Gotlib & A. Brass V7B126C "B Is For Bully: Accompaniment Tape A. Gotlib & A. Brass V7B127D "Bugz"- Performance & Accompaniment CD J. Jacobson & J. Higgins V7B127 "Bugz"- Teachers Manual- Repro Pack J. Jacobson & J. Higgins V1D123 c.1 "Cats"- Vocal Selections Hal Leonard V1D123 c.2 "Cats"- Vocal Selections Hal Leonard V6D004 "Joy To The World"- 15 Sacred Carols for Christmas- John Rutter Hinshaw V7B129 "The Family Feud"- Teacher's Manual with Performance & Accompaniment CD L. Fiftal V1B111 (A) The Big Red Bus (B) Grandfather Clock V1B117 (A) The Squirrel (B) Little Silver Fishes T. Dunhill V5D *See V4D002 Reflections of Canada Vol.2 (SSA, SAT, SAB) V7D001 …And A Glass Slipper L. I. Fallis V1D013 120 Christmas Songs (Voice and Piano) D. Nelson V1D050 40 French Hits of Our Times (Bk. 7) MCA V1D067 60 Silly Songs R. Edison V1B068 A Bag of Tools J.L. Hodd V4A023 A Blessing S. Porterfield V1C029 A Carol of Peace E. Thiman V6A061 A Celtic Prayer B. Peters V6C027 A Child Is Born M. Weir V3B231 A Child of Song D. Herring/ A. Beck V3A062 A Child's Credo Greg Gilpin V3B146 A Child's Hope M. Donnelly V1C002 A Christmas Carol J. Broeck V7C005 A Christmas Carol B. Treharne V7C046 A Christmas Carol L. Averill V7C065 c.1 A Christmas Carol J. Higgins V7C065 c.2 A Christmas Carol J. -

Crisis & Creativity • Dream Gifted Music

Crisis&Creativity•DreamGiftedMusic Since1982 Vol.21No1 $5.95USA $7.25Canada AJournalExploringDreams&Mythology Dreaming for Peace Quilt Awakening:ACreativeResponse•FaribaBogzaran Music,Mystery&theDreamingProcess•AmyMindell BlowingtheMind/HealingtheSoul•TalkswithRobertBoznakVol.21No.1/DreamNetwork 1 OnDreams&Art:WhereDreamers&ActorsMeet•MontagueUllman StatementofPurpose ©2002 DreamNetwork Ourpurposeistoraiseindividualandculturalapprecia- tionforthevalueofdreamsandtodisseminateinformation ISSN#1054-6707 thatwillassistandempowerusintakingresponsibilityforour Spring2002 cultural,emotionalandspiritualwell-beingwiththehelpof 1337PowerhouseLane,Ste22 dreams&mythology.Ourgoalsaretouniteandservethose POBox1026 whorespectdreams,toempowerdreamersindemystifying Moab,UT84532-1026 dreamworkandtoassistwiththeintegrationofdreamsharing Phone:435/259-5936 intoourculture,inwhateverwaysofintegrityareshownand www://DreamNetwork.net givenus. [email protected] Webelievethatdreamsareagentsforchangeandoften revealimportantnewinsightsaboutthelifeofthedreamer, bothpersonalandcultural.Recallingadreamisasignalthat wearereadytounderstandtheinformationthathasbeen Founder presented.Enactingthedream'shintcanbringpersonalem- WilliamR.Stimson,Ph.D. powerment. CouncilofAdvisors Weseektoprovideabalanceandtogiveallnations,voices StanleyKrippner,Ph.D. andschoolsofthoughtanopportunitytobeheard. RussellA.Lockhart,Ph.D. Therewillbetimeswhenaparticularareaofinterestwillbe RobertMoss givengreateremphasisthananotherbecauseofthelimited Graywolf/FredSwinney,M.A. spaceintheJournalandthatwhichissurfacingthatisof -

Thriving Stories of Success Redefined

THRIVING STORIES OF SUCCESS REDEFINED Pavithra KL, Sheetal Lydia and Sreehari Ravindranath ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This report is a result of years of our work with young people who inspire us to be the life skills champions the sector needs and create a movement that looks at thriving as not only academic or professional success, but the ability to make choices that lead to the redefinition of what success looks like. This report is authored by Pavithra KL, Sheetal Lydia Prasad and Sreehari R who have more than 10 years of field experience of working with young people and understand how important it is for the authentic voice and stories of young people who come from adverse backgrounds to be heard to influence sectoral mindset of what thriving looks like in 21st century. All great minds do not work in solidarity! They are guided to think outside the box; We are thankful to and fortunate enough to get constant encouragement, support and guidance from Suchetha Bhat and Vishal Talreja for bringing in new perspective to the Career Connect team that helped bring this report together. PREFACE Founded in 1999, Dream a Dream has been working towards empowering young people from vulnerable backgrounds to overcome adversity and prepare them to flourish in a fast-changing world. Over the years, we have impacted the lives of over 1 million children through our creative life skills approach. In this report, we have highlighted the impact of our After- School Life Skills Programme, the Career Connect Programme and the Teacher Development Programme for the year 2018-19. -

Adobe PDF Version of All the Lyrics

Ella Fitzgerald -Lyrics- Dedicado a Vickita 2 Ella Fitzgerald Ella Fitzgerald 3 - A - Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive.................................................................................................. 13 Ace In The Hole...................................................................................................................... 14 Alexander's Ragtime Band...................................................................................................... 15 All By Myself.......................................................................................................................... 16 All My Life ............................................................................................................................. 17 All Of You .............................................................................................................................. 18 All The Things You Are ......................................................................................................... 19 All Through The Night ........................................................................................................... 20 All Too Soon........................................................................................................................... 21 Always .................................................................................................................................... 22 Angel Eyes ............................................................................................................................. -

Dream a Dream Impact Report

2014-2015 DREAM A DREAM IMPACT REPORT The Impact Report is a comprehensive document that details out the impact created by Dream a Dream through its various programmes using the Life Skills Approach. Table of Contents Impact Report 2014-2015: Executive Summary ........................................................... 2 Impact Analysis: After School Life Skills Programme ................................................ 6 Part 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 Part 2: Story of Yeshwanth ................................................................................................... 7 Part 3: Impact Summary of Lords Convent English High School ...................... 9 Part 4: Impact Summary of Programme .................................................................... 11 Part 5: The relation between Baseline and Improvement ............................... 14 Part 6: Impact of other factors on Programme Efficiency ................................ 14 Part 7: Conclusion ................................................................................................................. 20 Impact Analysis: Career Connect Programme ............................................................. 21 Part 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. 21 Part 2: Story of Hajira ......................................................................................................... -

The Interpretation of Dreams Sigmund Freud (1900)

The Interpretation of Dreams Sigmund Freud (1900) PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION Wheras there was a space of nine years between the first and second editions of this book, the need of a third edition was apparent when little more than a year had elapsed. I ought to be gratified by this change; but if I was unwilling previously to attribute the neglect of my work to its small value, I cannot take the interest which is now making its appearance as proof of its quality. The advance of scientific knowledge has not left The Interpretation of Dreams untouched. When I wrote this book in 1899 there was as yet no "sexual theory," and the analysis of the more complicated forms of the psychoneuroses was still in its infancy. The interpretation of dreams was intended as an expedient to facilitate the psychological analysis of the neuroses; but since then a profounder understanding of the neuroses has contributed towards the comprehension of the dream. The doctrine of dream-interpretation itself has evolved in a direction which was insufficiently emphasized in the first edition of this book. From my own experience, and the works of Stekel and other writers, [1] I have since learned to appreciate more accurately the significance of symbolism in dreams (or rather, in unconscious thought). In the course of years, a mass of data has accumulated which demands consideration. I have endeavored to deal with these innovations by interpolations in the text and footnotes. If these additions do not always quite adjust themselves to the framework of the treatise, or if the earlier text does not everywhere come up to the standard of our present knowledge, I must beg indulgence for this deficiency, since it is only the result and indication of the increasingly rapid advance of our science. -

Music As of SCN Media Center Catalog 10/20/2014

SCN Media Center Catalog Music as of 10/20/2014 Music A Love So Strong Sherman, Kathy, CSJ CD 1 42:37 2011 Thirteen songs sung by Kathy Sherman. I Come to Know You Singing Bird Love So Strong Come Walk with Us What If We Believe In the Becoming I Give Thanks to God It's3:23 in the Morning Peace Prints on the World Love Bears All Things Tell It Like It Is Now Is All You Need Let Your Light All Is One Sherman, Kathy, CSJ CD 1 69 min. 2006 Twenty songs for rituals, gatherings justice, liturgy and meditation. All My Days: Instrumental Music for Quiet Reflection Schutte, Dan CD 1 55 min. 2006 All My Days, the latest collection of instrumental tracks from Dan Schutte, provides over 50 minutes of gentle, quiet reflective music for background for personal prayer. This CD includes piano, oboe, flute, cello, violin and other strings. All the Seasons of George Winston Winston, George CD 1 63 min. 1998 Piano solos of radio hits of the 50's and 60's. Page 1 of 103 Music All Time Great Rags Joplin, Scott CD 1 71 min. 2000 Eighteen selections from the best known of all ragtime composers. Allegri Miserere Phillips, Peter, Director CD 1 69 min. 1980 orig. 1990 Finest music from the Golden Age that has more performances than any other sacred music selections. Always With You Sherman, Kathy, CSJ Cassette Tape 2003 Eight spiritual hymns. Always With You Sherman, Kathy, CSJ CD 1 56 min. 2003 Slection of meditative songs for your own personal reflection. -

Holiday Dvds HOLIDAY Dvds

Town of Randall • Town of Salem • Village of Paddock Lake Holiday Village of Silver Lake • Village of Twin Lakes DVDs HOLIDAY DVDs 24615 89th Street 729 S. Cogswell Drive 110 S. Lake Avenue Salem, WI 53168 Silver Lake, WI 53170 Twin Lakes, WI 53181 262-843-3348 262-889-4606 262-877-4281 www.communitylib.org www.communitylib.org Need more reading suggestions? Call or stop by the Info Desk at any location or visit us online! Christmas Easter A Christmas Carol (animated) 2010 SALEM : DVDFEATURE DVD CHR TWIN LAKES : DVDFEATURE DVD CHR A Christmas Carol (George C. Scott) 1999 Twas the night before Easter/ 2011 Twin Lakes DVDFEATURE DVD CHR Veggie Tales SALEM : DVDCHILDRENS J DVD 791.4572 VEG A Christmas story 1983 SALEM : DVDFEATURE DVD CHR A Colbert Christmas 2008 Dora the Explorer: Egg Hunt 2003 SALEM : DVD DVD 791.4572 COL SALEM : DVDCHILDRENS J DVD 791.4572 DOR A Song for the Season 2011 SALEM : DVDFEATURE DVD SON Hop 2012 All I Want for Christmas 2008 SALEM : DVDFEATURE DVD HOP SALEM : DVDFEATURE DVD ALL TWIN LAKES : DVDFEATURE DVD HOP All She Wants for Christmas 2008 SALEM : DVDFEATURE DVD ALL Max Lucado's Hermie & Friends 2006 SALEM : DVDFEATURE J DVD BUZ Baby Santa's music box 2004 SALEM : DVDCHILDRENS J DVD 372.87 BAB Beauty and the Beast: 2002 SALEM : DVDFEATURE DVD BEA Veggie Tales: a lesson in using your 2005 gifts for good. Lord of the beans The Enchanted Christmas Blizzard 2005 SILVER LAKE : DVDCHILDRENS J DVD 248.4 TWIN LAKES : DVDFEATURE DVD BLI VEG Christmas Snow 2004 SALEM : DVDFEATURE DVD CHR Christmas with the Kranks 2004