1 Terrestrial Planets Are Planets Made up of Rocks Or Metals with a Hard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

Callisto: a Guide to the Origin of the Jupiter System

A PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE DECADAL SURVEY ON PLANETARY SCIENCE AND ASTROBIOLOGY Callisto: A Guide to the Origin of the Jupiter System David E Smith 617-803-3377 Department of Earth, Atmospheric and PLanetary Sciences Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge MA 02139 [email protected] Co-authors: Francis Nimmo, UCSC, [email protected] Krishan Khurana, UCLA, [email protected] Catherine L. Johnson, PSI, [email protected] Mark Wieczorek, OCA, Fr, [email protected] Maria T. Zuber, MIT, [email protected] Carol Paty, University of Oregon, [email protected] Antonio Genova, Univ Rome, It, [email protected] Erwan Mazarico, NASA GSFC, [email protected] Louise Prockter, LPI, [email protected] Gregory A. Neumann, NASA GSFC Emeritus, [email protected] John E. Connerney, Adnet Systems Inc., [email protected] Edward B. Bierhaus, LMCO, [email protected] Sander J. Goossens, UMBC, [email protected] MichaeL K. Barker, NASA GSFC, [email protected] Peter B. James, Baylor, [email protected] James Head, Brown, [email protected] Jason Soderblom, MIT, [email protected] July 14, 2020 Introduction Among the GaLiLean moons of Jupiter, it is outermost CaLListo that appears to most fulLy preserve the record of its ancient past. With a surface aLmost devoid of signs of internaL geologic activity, and hints from spacecraft data that its interior has an ocean whiLe being only partiaLLy differentiated, CaLListo is the most paradoxicaL of the giant rock-ice worlds. How can a body with such a primordiaL surface harbor an ocean? If the interior was warm enough to form an ocean, how could a mixed rock and ice interior remain stable? What do the striking differences between geologicaLLy unmodified CaLListo and its sibling moon Ganymede teLL us about the formation of the GaLiLean moons and the primordiaL conditions at the time of the formation of CaLListo and the accretion of giant planet systems? The answers can be provided by a CaLListo orbitaL mission. -

Modern Astronomical Optics - Observing Exoplanets 2

Modern Astronomical Optics - Observing Exoplanets 2. Brief Introduction to Exoplanets Olivier Guyon - [email protected] – Jim Burge, Phil Hinz WEBSITE: www.naoj.org/staff/guyon → Astronomical Optics Course » → Observing Exoplanets (2012) Definitions – types of exoplanets Planet (& exoplanet) definitions are recent, as, prior to discoveries of exoplanets around other stars and dwarf planets in our solar system, there was no need to discuss lower and upper limits of planet masses. Asteroid < dwarf planet < planet < brown dwarf < star Upper limit defined by its mass: < 13 Jupiter mass 1 Jupiter mass = 317 Earth mass = 1/1000 Sun mass Mass limit corresponds to deuterium limit: a planet is not sufficiently massive to start nuclear fusion reactions, of which deuterium burning is the easiest (lowest temperature) Lower limit recently defined (now excludes Pluto) for our solar system: has cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit Distinction between giant planets (massive, large, mostly gas) and rocky planets also applies to exoplanets Habitable planet: planet on which life as we know it (bacteria, planets or animals) could be sustained = rocky + surface temperature suitable for liquid water Formation Planet and stars form (nearly) together, within first few x10 Myr of system formation Gravitational collapse of gas + dust cloud Star is formed at center of disk Planets form in the protoplanetary disk Planet embrios form first Adaptive Optics image of Beta Pic Large embrios (> few Earth mass) can Shows planet + debris disk accrete large quantity of -

Introduction to Astronomy from Darkness to Blazing Glory

Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory Published by JAS Educational Publications Copyright Pending 2010 JAS Educational Publications All rights reserved. Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Second Edition Author: Jeffrey Wright Scott Photographs and Diagrams: Credit NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USGS, NOAA, Aames Research Center JAS Educational Publications 2601 Oakdale Road, H2 P.O. Box 197 Modesto California 95355 1-888-586-6252 Website: http://.Introastro.com Printing by Minuteman Press, Berkley, California ISBN 978-0-9827200-0-4 1 Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory The moon Titan is in the forefront with the moon Tethys behind it. These are two of many of Saturn’s moons Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, ISS, JPL, ESA, NASA 2 Introduction to Astronomy Contents in Brief Chapter 1: Astronomy Basics: Pages 1 – 6 Workbook Pages 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Time: Pages 7 - 10 Workbook Pages 3 - 4 Chapter 3: Solar System Overview: Pages 11 - 14 Workbook Pages 5 - 8 Chapter 4: Our Sun: Pages 15 - 20 Workbook Pages 9 - 16 Chapter 5: The Terrestrial Planets: Page 21 - 39 Workbook Pages 17 - 36 Mercury: Pages 22 - 23 Venus: Pages 24 - 25 Earth: Pages 25 - 34 Mars: Pages 34 - 39 Chapter 6: Outer, Dwarf and Exoplanets Pages: 41-54 Workbook Pages 37 - 48 Jupiter: Pages 41 - 42 Saturn: Pages 42 - 44 Uranus: Pages 44 - 45 Neptune: Pages 45 - 46 Dwarf Planets, Plutoids and Exoplanets: Pages 47 -54 3 Chapter 7: The Moons: Pages: 55 - 66 Workbook Pages 49 - 56 Chapter 8: Rocks and Ice: -

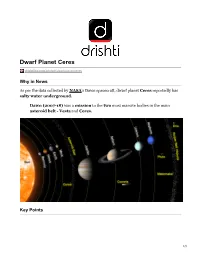

Dwarf Planet Ceres

Dwarf Planet Ceres drishtiias.com/printpdf/dwarf-planet-ceres Why in News As per the data collected by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft, dwarf planet Ceres reportedly has salty water underground. Dawn (2007-18) was a mission to the two most massive bodies in the main asteroid belt - Vesta and Ceres. Key Points 1/3 Latest Findings: The scientists have given Ceres the status of an “ocean world” as it has a big reservoir of salty water underneath its frigid surface. This has led to an increased interest of scientists that the dwarf planet was maybe habitable or has the potential to be. Ocean Worlds is a term for ‘Water in the Solar System and Beyond’. The salty water originated in a brine reservoir spread hundreds of miles and about 40 km beneath the surface of the Ceres. Further, there is an evidence that Ceres remains geologically active with cryovolcanism - volcanoes oozing icy material. Instead of molten rock, cryovolcanoes or salty-mud volcanoes release frigid, salty water sometimes mixed with mud. Subsurface Oceans on other Celestial Bodies: Jupiter’s moon Europa, Saturn’s moon Enceladus, Neptune’s moon Triton, and the dwarf planet Pluto. This provides scientists a means to understand the history of the solar system. Ceres: It is the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It was the first member of the asteroid belt to be discovered when Giuseppe Piazzi spotted it in 1801. It is the only dwarf planet located in the inner solar system (includes planets Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars). Scientists classified it as a dwarf planet in 2006. -

![Arxiv:2005.14671V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 30 Jun 2020 Tion Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8147/arxiv-2005-14671v2-astro-ph-ep-30-jun-2020-tion-et-al-408147.webp)

Arxiv:2005.14671V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 30 Jun 2020 Tion Et Al

Draft version July 1, 2020 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX62 The Gaia-Kepler Stellar Properties Catalog. II. Planet Radius Demographics as a Function of Stellar Mass and Age Travis A. Berger,1 Daniel Huber,1 Eric Gaidos,2 Jennifer L. van Saders,1 and Lauren M. Weiss1 1Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai`i, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 2Department of Earth Sciences, University of Hawai`i at M¯anoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA ABSTRACT Studies of exoplanet demographics require large samples and precise constraints on exoplanet host stars. Using the homogeneous Kepler stellar properties derived using Gaia Data Release 2 by Berger et al.(2020), we re-compute Kepler planet radii and incident fluxes and investigate their distributions with stellar mass and age. We measure the stellar mass dependence of the planet radius valley to +0:21 be d log Rp/d log M? = 0:26−0:16, consistent with the slope predicted by a planet mass dependence on stellar mass (0.24{0.35) and core-powered mass-loss (0.33). We also find first evidence of a stellar age dependence of the planet populations straddling the radius valley. Specifically, we determine that the fraction of super-Earths (1{1.8 R⊕) to sub-Neptunes (1.8{3.5 R⊕) increases from 0.61 ± 0.09 at young ages (< 1 Gyr) to 1.00 ± 0.10 at old ages (> 1 Gyr), consistent with the prediction by core-powered mass- loss that the mechanism shaping the radius valley operates over Gyr timescales. Additionally, we find a tentative decrease in the radii of relatively cool (Fp < 150 F⊕) sub-Neptunes over Gyr timescales, which suggests that these planets may possess H/He envelopes instead of higher mean molecular weight atmospheres. -

Outer Planets: the Ice Giants

Outer Planets: The Ice Giants A. P. Ingersoll, H. B. Hammel, T. R. Spilker, R. E. Young Exploring Uranus and Neptune satisfies NASA’s objectives, “investigation of the Earth, Moon, Mars and beyond with emphasis on understanding the history of the solar system” and “conduct robotic exploration across the solar system for scientific purposes.” The giant planet story is the story of the solar system (*). Earth and the other small objects are leftovers from the feast of giant planet formation. As they formed, the giant planets may have migrated inward or outward, ejecting some objects from the solar system and swallowing others. The giant planets most likely delivered water and other volatiles, in the form of icy planetesimals, to the inner solar system from the region around Neptune. The “gas giants” Jupiter and Saturn are mostly hydrogen and helium. These planets must have swallowed a portion of the solar nebula intact. The “ice giants” Uranus and Neptune are made primarily of heavier stuff, probably the next most abundant elements in the Sun – oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. For each giant planet the core is the “seed” around which it accreted nebular gas. The ice giants may be more seed than gas. Giant planets are laboratories in which to test our theories about geophysics, plasma physics, meteorology, and even oceanography in a larger context. Their bottomless atmospheres, with 1000 mph winds and 100 year-old storms, teach us about weather on Earth. The giant planets’ enormous magnetic fields and intense radiation belts test our theories of terrestrial and solar electromagnetic phenomena. -

The Solar System Cause Impact Craters

ASTRONOMY 161 Introduction to Solar System Astronomy Class 12 Solar System Survey Monday, February 5 Key Concepts (1) The terrestrial planets are made primarily of rock and metal. (2) The Jovian planets are made primarily of hydrogen and helium. (3) Moons (a.k.a. satellites) orbit the planets; some moons are large. (4) Asteroids, meteoroids, comets, and Kuiper Belt objects orbit the Sun. (5) Collision between objects in the Solar System cause impact craters. Family portrait of the Solar System: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, (Eris, Ceres, Pluto): My Very Excellent Mother Just Served Us Nine (Extra Cheese Pizzas). The Solar System: List of Ingredients Ingredient Percent of total mass Sun 99.8% Jupiter 0.1% other planets 0.05% everything else 0.05% The Sun dominates the Solar System Jupiter dominates the planets Object Mass Object Mass 1) Sun 330,000 2) Jupiter 320 10) Ganymede 0.025 3) Saturn 95 11) Titan 0.023 4) Neptune 17 12) Callisto 0.018 5) Uranus 15 13) Io 0.015 6) Earth 1.0 14) Moon 0.012 7) Venus 0.82 15) Europa 0.008 8) Mars 0.11 16) Triton 0.004 9) Mercury 0.055 17) Pluto 0.002 A few words about the Sun. The Sun is a large sphere of gas (mostly H, He – hydrogen and helium). The Sun shines because it is hot (T = 5,800 K). The Sun remains hot because it is powered by fusion of hydrogen to helium (H-bomb). (1) The terrestrial planets are made primarily of rock and metal. -

THE PENNY MOON and QUARTER EARTH School Adapted from a Physics Forum Activity At

~ LPI EDUCATION/PUBLIC OUTREACH SCIENCE ACTIVITIES ~ Ages: 5th grade – high THE PENNY MOON AND QUARTER EARTH school Adapted from a Physics Forum activity at: http://www.phvsicsforums.com/ Duration: 10 minutes OVERVIEW — The students will use a penny and a quarter to model the Moon’s rotation on its axis and Materials: revolution around the Earth, and demonstrate that the Moon keeps the same face toward One penny and one the Earth. quarter per pair of students OBJECTIVE — Overhead projector, or The students will: elmo, or video Demonstrate the motion of the Moon’s rotation and revolution. projector Compare what we would see of the Moon if it did not rotate to what we see when its period of rotation is the same as its orbital period. Projected image of student overhead BEFORE YOU START: Do not introduce this topic along with the reason for lunar phases; students may become confused and assume that the Moon’s rotation is related to its phases. Prepare to show the student overhead projected for the class to see. ACTIVITY — 1. Ask your students to describe which parts of the Moon they see. Does the Moon turn? Can we see its far side? Allow time for your students to discuss this and share their opinions. 2. Hand out the pennies and quarters so that each pair of students has both. Tell the students that they will be creating a model of the Earth and Moon. Which object is Earth? [the quarter] Which one is the Moon? [the penny] 3. Turn on the projected student overhead. -

Discovery of a Low-Mass Companion to a Metal-Rich F Star with the Marvels Pilot Project

The Astrophysical Journal, 718:1186–1199, 2010 August 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/718/2/1186 C 2010. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. DISCOVERY OF A LOW-MASS COMPANION TO A METAL-RICH F STAR WITH THE MARVELS PILOT PROJECT Scott W. Fleming1,JianGe1, Suvrath Mahadevan1,2,3, Brian Lee1, Jason D. Eastman4, Robert J. Siverd4, B. Scott Gaudi4, Andrzej Niedzielski5, Thirupathi Sivarani6, Keivan G. Stassun7,8, Alex Wolszczan2,3, Rory Barnes9, Bruce Gary7, Duy Cuong Nguyen1, Robert C. Morehead1, Xiaoke Wan1, Bo Zhao1, Jian Liu1, Pengcheng Guo1, Stephen R. Kane1,10, Julian C. van Eyken1,10, Nathan M. De Lee1, Justin R. Crepp1,11, Alaina C. Shelden1,12, Chris Laws9, John P. Wisniewski9, Donald P. Schneider2,3, Joshua Pepper7, Stephanie A. Snedden12, Kaike Pan12, Dmitry Bizyaev12, Howard Brewington12, Olena Malanushenko12, Viktor Malanushenko12, Daniel Oravetz12, Audrey Simmons12, and Shannon Watters12,13 1 Department of Astronomy, University of Florida, 211 Bryant Space Science Center, Gainesville, FL 326711-2055, USA; scfl[email protected]fl.edu 2 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, The Pennsylvania State University, 525 Davey Laboratory, University Park, PA 16802, USA 3 Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA 4 Department of Astronomy, The Ohio State University, 140 West 18th Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 5 Torun´ Center for Astronomy, Nicolaus Copernicus University, ul. Gagarina 11, 87-100, Torun,´ Poland 6 Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bangalore 560034, India 7 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, USA 8 Department of Physics, Fisk University, 1000 17th Ave. -

Oil, Earth Mass and Gravitational Force

A peer reviewed version is published at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.127 Oil, Earth mass and gravitational force Khaled Moustafa Editor of the Arabic Science Archive (ArabiXiv) E-mail: [email protected] Highlights Large amounts of fossil fuels are extracted annually worldwide. Would the extracted amounts represent any significant percentage of the Earth mass? What would be the consequence on Earth structure and its gravitational force? Modeling the potential loss of Earth mass might be required. Efforts for alternative renewable energy sources should be enhanced. Abstract Fossil fuels are intensively extracted from around the world faster than they are renewed. Regardless of direct and indirect effects of such extractions on climate change and biosphere, another issue relating to Earth’s internal structure and Earth mass should receive at least some interest. According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), about 34 billion barrels of oil (~4.7 billion metric tons) and 9 billion tons of coal have been extracted in 2014 worldwide. Converting the amounts of oil and coal extracted over the last 3 decades and their respective reserves, intended to be extracted in the future, into mass values suggests that about 355 billion tons, or ~ 5.86*10−9 (~ 0.0000000058) % of the Earth mass, would be ‘lost’. Although this is a tiny percentage, modeling the potential loss of Earth mass may help figuring out a critical threshold of mass loss that should not be exceeded. Here, I briefly discuss whether such loss would have any potential consequences on the Earth’s internal structure and on its gravitational force based on the Newton's law of gravitation that links the attraction force between planets to their respective masses and the distances that separate them. -

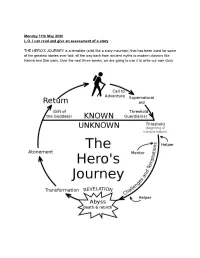

Monday 11Th May 2020 L.O. I Can Read and Give an Assessment of a Story

Monday 11th May 2020 L.O. I can read and give an assessment of a story THE HERO’S JOURNEY is a template (a bit like a story mountain) that has been used for some of the greatest stories ever told, all the way back from ancient myths to modern classics like Narnia and Star wars. Over the next three weeks, we are going to use it to write our own story One of the reasons STAR WARS is such a great movie is it because it follows the HERO’S JOURNEY model. Today, you are going to read / watch this version of the Hero’s journey and see how it fits into the format for our first act! The subtitles just refer to the stages of the story - don’t worry about them yet! Just read the story and if you have internet access look up / click on the clips on youtube. ORDINARY WORLD Luke Skywalker was a poor and humble boy who lived with his aunt and uncle in a scorching and desolate planet world called Tatooine. His job was to fix robots on the family farm and and he spent his free time flying planes through the rocky canyons. He loved his aunt and uncle but dreamed of a more exciting and adventurous life https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wJa1L1ZCqU Search for ‘Luke Skywalker binary sunset’ CALL TO ADVENTURE One day, Luke found a broken old R2 astromech droid. It was called R2-D2 and it was a mischievous, cheeky robot who made lots of bleeps and flashes.